Timna Valley

The Timna Valley is located in southern Israel in the southwestern Arabah, approximately 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of the Gulf of Aqaba and the town of Eilat. The area is rich in copper ore and has been mined since the 5th millennium BCE. There is controversy whether the mines were active during the Kingdom of Israel and the biblical King Solomon.[1]

A large section of the valley, containing ancient remnants of copper mining and ancient worship, is encompassed in a recreation park.

In July 2011, the Israeli government approved the construction of an international airport, the Timna Airport, in the Timna valley.[2]

History

Copper mining

Copper has been mined in the area since the 5th or 6th millennium BCE.[3] Archaeological excavation indicates that the copper mines in Timna Valley were probably part of the Kingdom of Edom and worked by the Edomites, described as biblical foes of the Israelites,[4] during the 10th century BCE, the period of the biblical King Solomon.[5] Mining continued by the Israelites and Nabateans through to the Roman period and the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, and then by the Ummayads from the Arabian Peninsula after the Arab conquest (in the 7th century CE) until the copper ore became scarce.[6]

The copper was used for ornaments, but more importantly for stone cutting, as saws, in conjunction with sand.[7]

The recent excavations dating copper mining to the 10th century BCE also discovered what may be the earliest camel bones with signs of domestication found in Israel or even outside the Arabian peninsula, dating to around 930 BCE. This is seen as evidence by the excavators that the stories of Abraham, Joseph, Jacob and Esau were written or rewritten after this time seeing that the Biblical books frequently reference traveling with caravans of domesticated camels.[8][9]

Modern history

Scientific attention and public interest was aroused in the 1930s, when Nelson Glueck attributed the copper mining at Timna to King Solomon (10th century BCE) and named the site "King Solomon's Mines". These were considered by most archaeologists to be earlier than the Solomonic period until an archaeological excavation led by Erez Ben-Yosef of Tel Aviv University's found evidence indicating that this area was being mined by Edomites, a group who the Bible says were frequently at war with Israel.[10][11]

In 1959, Professor Beno Rothenberg, director of the Institute for Archeo-Metallurgical Studies at University College, London, led the Arabah Expedition, sponsored by the Eretz Israel Museum, and the Tel Aviv University Institute of Archaeology. The expedition included a deep excavation of Timna Valley, and by 1990 he discovered 10,000 copper mines and smelting camps with furnaces, rock drawings, geological features, shrines, temples, an Egyptian mining sanctuary, jewelry, and other artifacts never before found anywhere in the world.[12] His excavation and restoration of the area allowed for the reconstruction of Timna Valley’s long and complex history of copper production, from the Late Neolithic period to the Middle Ages.[13]

The modern state of Israel also began mining copper on the eastern edge of the valley in 1955, but ceased in 1976. The mine was reopened in 1980. The mine was named Timnah after a Biblical chief.[14]

Geological features

Timna Valley is notable for its uncommon stone formations and sand. Although predominantly red, the sand can be yellow, orange, grey, dark brown, or black. Light green or blue sand occurs near the copper mines. Water and wind erosion have created several unusual formations that are only found in similar climates.[6]

Solomon's Pillars

The most striking and well-known formation in Timna Valley are Solomon's Pillars. The pillars are natural structures that were formed by centuries of water erosion through fractures in the sandstone cliff until it became a series of distinct, pillar-shaped structures.[6]

American archaeologist Nelson Glueck caused a surge of attention for the pillars in the 1930s. He claimed that the pillars were related to King Solomon and gave them the name "Solomon's Pillars". Although his hypothesis lacked support and has not been accepted, the name stuck, and the claim gave the valley the attention that helped bring about the excavations and current national park.

The pillars are known as the backdrop for evening concerts and dance performances the park presents in the summer.[15]

Mushroom

The Mushroom is an unusual monolithic, mushroom-shaped, red sandstone rock formation known as a hoodoo. The mushroom shape was caused by wind, humidity, and water erosion over centuries.[15] The Mushroom is surrounded by copper ore smelting sites from between the 14th and 12th centuries BCE.[6]

Arches

The Arches are natural arches formed by erosion, as well, and can be seen along the western cliff of the valley. Arches are not as rare as Solomon's Pillars and the Mushroom, and similar structures can be found in elsewhere in the world. The walking trail that goes to the Arches also goes past the copper mine shafts.[6]

Archaeology

Shrine of Hathor

Beno Rothenberg, the main excavator of the Timna Valley area, excavated a small Egyptian temple dedicated to Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of mining, at the base of Solomon's Pillars. It was built during the reign of Pharaoh Seti I at the end of the 14th century BCE, for the Egyptian miners. The shrine housed an open courtyard with a cella, an area cut into the rock to presumably house a statue of the deity. Earthquake damage caused the temple to be rebuilt during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses II in the 13th century BCE, with a larger courtyard and more elaborate walls and floors. The dimensions of the original shrine were 15 by 15 meters, and it was faced with white sandstone that was found only at the mining site, several kilometers away. The hieroglyphics, sculptures, and jewelry found in the temple totaled several thousand artifacts, have provided a lot of important information for archaeologists.[16] A rock carving of Ramses III with Hathor is located at the top of a flight of step carved into the stone next to the shrine.[6] When the Egyptians left the area in the middle of the 12th century BCE, the Midianites continued using the temple. They erased the evidence of the Egyptian cult, effaced the images of Hathor and the Egyptian hieroglyphics, and built a row of stelae and a bench of offerings on both sides of the entrance. They turned the temple into a tented desert shrine and filled it with Midianite pottery and metal jewelry. There was also a bronze serpent found nearby the sanctuary.

Rock drawings

Many rock drawings are found throughout the valley that were contributed by different ruling empires over time. The Egyptians carved the most famous drawing, Chariots, consisting of Egyptians warriors holding axes and shields while driving ox-drawn chariots.[6] There is a road that leads visitors to the Chariots, located about two miles from the mines in a narrow valley.[15]

Archaeologists used the carvings to learn about the rituals and lifestyles of the various cultures that once ruled the area. They also provide information about the plants and animals of the area, in addition to the life and work of the people.

Recent excavations

Renewed archaeological investigations of copper exploitation at Timna began in 2009 when a team from UCSD led by Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef examined smelting camp Site 30. This site was first excavated by Rothenberg and dated to the Late Bronze Age (14th-12th centuries BCE) based on findings at the Shrine of Hathor; however, new results obtained using high precision radiocarbon dating of short-lived organic samples and archaeomagnetic dating of slag showed that major smelting activity happened in the early Iron Age (11th-9th centuries BCE).[17] This distinction is extremely important as the dating shift puts activity in the time of the United Monarchy of Israel—often referred to as the time of Kings David and Solomon.[18][19]

The Central Timna Valley project (also directed by Ben-Yosef of Tel Aviv University), which began in 2013, continues this previous work and "includes new excavations and surveys designed to address a number of critical issues in the Late Bronze and Iron Age archaeology of the southern Levant. These include the history of copper production technology and the introduction of iron, historical issues concerning the nature of 13th- to 9th-century BCE desert societies and the impact of the intense copper production on social processes, regional and global political interactions and the economy of the southern Levant at that period."[20]

Research and excavations during the first two seasons have focused on smelting camp Site 34 (“The Slaves’ Hill”/“Giv‘at Ha‘avadim”) and two mining areas in the park. The team has secured dating of major copper production at Site 34 to the early Iron Age (11th–9th centuries BCE) as well, confirming a larger picture of activity during this period.[20]

The team is also using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to date mining activity in the area of the Merkavot/Chariot rock drawings. Multiple forms of mining technology are exhibited there and span a period of approximately 6,000 years. No dateable material culture is found in or around most of the mines necessitating a new type of research technology to establish dating for each technique.[20]

Nature reserve

In 2002, 42,000 dunams in Timna Valley were declared a nature reserve, ending all mining activity within the reserve's area.[21] Gazelles and ibex still roam the area, but an image of these animals with ostriches found on a high ridge of sand suggests that ostriches once lived here, as well.

Timna Valley Park

Timna Valley Park was opened by the Jewish National Fund to share Rothenberg’s findings with the public, and there are around 20 different walking trails and some roads in the park to lead visitors to the various attractions. The Jewish National Fund, a non-profit organization that aids in the development of Israel, funded the creation of many of the non-historic tourist and family attractions and activities in the park.[12] The park includes a visitors recreation area with an artificial lake and a 4D film light-and-sound show.[22] The park is used as the location for open-air concerts and cliff-climbing events.[23] Because the park is not part of the national parks of Israel, there has been controversy over construction of hotels and a large tourist reserve in the area.[24][25]

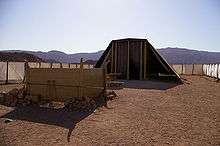

Replica of the tabernacle

A life-size replica of the biblical tabernacle, a tent that God is said to have instructed Moses to build in order to have a transportable sanctuary during the Exodus from Egypt to the Holy Land, was constructed in recent years in the park. It does not use the materials described in the Bible.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ New findings show Timna mines to have been active mainly during the period of the early Israelite kingdom (Tel Aviv University website, in Hebrew)

- ↑ http://www.haaretz.com/news/features/construction-on-israel-s-new-international-airport-takes-off.premium-1.526442

- ↑ Ian Shaw (2002). A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (September 5, 2013). "Reality check on King Solomon's mines: Right era, wrong kingdom". NBC News. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Proof of Solomon's mines found in Israel". Phys.org. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Timna Park Official site. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Ancient Egyptian copper slabbing saws. The article includes an extensive bibliography. ('Unforbidden Geology' a former GeoCities website)

- ↑ Hasson, Nir (January 17, 2014). "Hump stump solved: Camels arrived in region much later than biblical reference". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ Noble Wilford, John (10 February 2014). "Camels Had No Business in Genesis". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "Proof of Solomon's mines found in Israel". Phys.org. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ↑ "Proof of Solomon's mines found in Israel". The Jewish Press. September 8, 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- 1 2 Jewish National Fund

- ↑ "Archaeological Sites in Israel - Timna: Valley of the Ancient Copper Mines" Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Karṭa (Firm) (1993). Carta's official guide to Israel: and complete gazetteer to all sites in the Holy Land. State of Israel, Ministry of Defence Pub. House. p. 462. ISBN 978-965-220-186-7. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Timna Valley Park Review" Frommer's. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Holiday in Israel

- ↑ Ben-Yosef, Erez; Shaar, Ron; Tauxe, Lisa; Hagai, Rom (2012). "A New Chronological Framework for Iron Age Copper Production at Timna (Israel)". BASOR. 367: 31. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.367.0031. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.367.0031.

- ↑ Hasson, Nir (3 September 2013). "Date and olive pits dispel mystery of King Solomon's mines". Haaretz. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ Bennett-Smith, Meredith (6 September 2013). "King Solomon-Era Mines Were Misattributed To Ancient Egyptians, Researchers Say". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Central Timna Valley Project".

- ↑ "List of National Parks and Nature Reserves" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ See the Timna Park official website

- ↑ Image of the Timna copper snake and of the tabernacle stake holes

- ↑ About the campaign against construction in Timna from 1995 till 2010 (Hebrew, The Israeli Society for Protection of Nature website)

- ↑ Court stymies Timna hotel development Jerusalem Post article from 2009

- ↑ "Tabernacle Model" Bible Places. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- J.M. Tebes, "A Land whose Stones are Iron, and out of whose Hills You can Dig Copper": The Exploitation and Circulation of Copper in the Iron Age Negev and Edom, DavarLogos 6/1 (2007)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Timna valley. |

Coordinates: 29°47′16″N 34°59′20″E / 29.78778°N 34.98889°E