Triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.[1] For example, the triple point of mercury occurs at a temperature of −38.83440 °C and a pressure of 0.2 mPa.

In addition to the triple point for solid, liquid, and gas phases, a triple point may involve more than one solid phase, for substances with multiple polymorphs. Helium-4 is a special case that presents a triple point involving two different fluid phases (lambda point).[1]

The triple point of water is used to define the kelvin, the base unit of thermodynamic temperature in the International System of Units (SI).[2] The value of the triple point of water is fixed by definition, rather than measured. The triple points of several substances are used to define points in the ITS-90 international temperature scale, ranging from the triple point of hydrogen (13.8033 K) to the triple point of water (273.16 K, 0.01 °C, or 32.018 °F).

The term "triple point" was coined in 1873 by James Thomson, brother of Lord Kelvin.[3]

Triple point of water

Gas–liquid–solid triple point

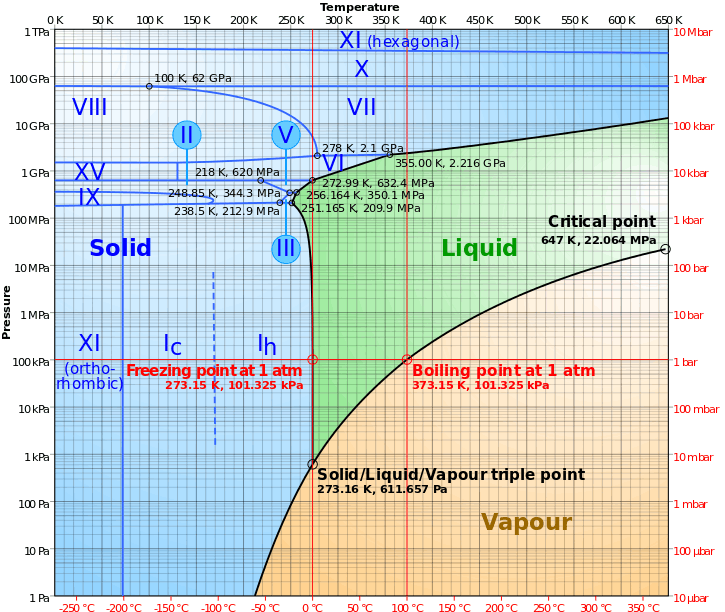

The single combination of pressure and temperature at which liquid water, solid ice, and water vapor can coexist in a stable equilibrium occurs at exactly 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F) and a partial vapor pressure of 611.657 pascals (6.11657 mbar; 0.00603659 atm).[4][5] At that point, it is possible to change all of the substance to ice, water, or vapor by making arbitrarily small changes in pressure and temperature. Even if the total pressure of a system is well above the triple point of water, provided that the partial pressure of the water vapor is 611.657 pascals, then the system can still be brought to the triple point of water. Strictly speaking, the surfaces separating the different phases should also be perfectly flat, to negate the effects of surface tension.

The gas–liquid–solid triple point of water corresponds to the minimum pressure at which liquid water can exist. At pressures below the triple point (as in outer space), solid ice when heated at constant pressure is converted directly into water vapor in a process known as sublimation. Above the triple point, solid ice when heated at constant pressure first melts to form liquid water, and then evaporates or boils to form vapor at a higher temperature.

For most substances the gas–liquid–solid triple point is also the minimum temperature at which the liquid can exist. For water, however, this is not true because the melting point of ordinary ice decreases as a function of pressure, as shown by the dotted green line in the phase diagram. At temperatures just below the triple point, compression at constant temperature transforms water vapor first to solid and then to liquid (water ice has lower density than liquid water, so increasing pressure leads to a liquefaction).

The triple point pressure of water was used during the Mariner 9 mission to Mars as a reference point to define "sea level". More recent missions use laser altimetry and gravity measurements instead of pressure to define elevation on Mars.[6]

High pressure phases

At high pressures, water has a complex phase diagram with 15 known phases of ice and several triple points including ten whose coordinates are shown in the diagram. For example, the triple point at 251 K (−22 °C) and 210 MPa (2070 atm) corresponds to the conditions for the coexistence of ice Ih (ordinary ice), ice III and liquid water, all at equilibrium. There are also triple points for the coexistence of three solid phases, for example ice II, ice V and ice VI at 218 K (−55 °C) and 620 MPa (6120 atm).

For those high-pressure forms of ice which can exist in equilibrium with liquid, the diagram shows that melting points increase with pressure. At temperatures above 273 K (0 °C), increasing the pressure on water vapor results first in liquid water and then a high-pressure form of ice. In the range 251–273 K, ice I is formed first, followed by liquid water and then ice III or ice V, followed by other still denser high-pressure forms.

Triple point cells

Triple point cells are used in the calibration of thermometers. For exacting work, triple point cells are typically filled with a highly pure chemical substance such as hydrogen, argon, mercury, or water (depending on the desired temperature). The purity of these substances can be such that only one part in a million is a contaminant, called "six nines" because it is 99.9999% pure. When it is a water-based cell, a special isotopic composition called VSMOW is used because it is very pure and produces temperatures that are more comparable from lab to lab. Triple point cells are so effective at achieving highly precise, reproducible temperatures, an international calibration standard for thermometers called ITS–90 relies upon triple point cells of hydrogen, neon, oxygen, argon, mercury, and water for delineating six of its defined temperature points.

Table of triple points

This table lists the gas–liquid–solid triple points of several substances. Unless otherwise noted, the data comes from the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (now NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology).[7]

| Substance | T [K] (°C) | p [kPa]* (atm) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylene | 192.4 K (−80.7 °C) | 120 kPa (1.2 atm) |

| Ammonia | 195.40 K (−77.75 °C) | 6.076 kPa (0.05997 atm) |

| Argon | 83.81 K (−189.34 °C) | 68.9 kPa (0.680 atm) |

| Arsenic | 1,090 K (820 °C) | 3,628 kPa (35.81 atm) |

| Butane[8] | 134.6 K (−138.6 °C) | 7× 10−4 kPa |

| Carbon (graphite) | 4,765 K (4,492 °C) | 10,132 kPa (100.00 atm) |

| Carbon dioxide | 216.55 K (−56.60 °C) | 517 kPa (5.10 atm) |

| Carbon monoxide | 68.10 K (−205.05 °C) | 15.37 kPa (0.1517 atm) |

| Chloroform[9] | 175.43 K (−97.72 °C) | 0.870 kPa (0.00859 atm) |

| Deuterium | 18.63 K (−254.52 °C) | 17.1 kPa (0.169 atm) |

| Ethane | 89.89 K (−183.26 °C) | 8 × 10−4 kPa |

| Ethanol[10] | 150 K (−123 °C) | 4.3 × 10−7 kPa |

| Ethylene | 104.0 K (−169.2 °C) | 0.12 kPa (0.0012 atm) |

| Formic acid[11] | 281.40 K (8.25 °C) | 2.2 kPa (0.022 atm) |

| Helium-4 (lambda point)[12] | 2.1768 K (−270.9732 °C) | 5.048 kPa (0.04982 atm) |

| Helium-4 (hcp−bcc−He-II)[13] | 1.463 K (−271.687 °C) | 26.036 kPa (0.25696 atm) |

| Helium-4 (bcc−He-I−He-II)[13] | 1.762 K (−271.388 °C) | 29.725 kPa (0.29336 atm) |

| Helium-4 (hcp−bcc−He-I)[13] | 1.772 K (−271.378 °C) | 30.016 kPa (0.29623 atm) |

| Hexafluoroethane[14] | 173.08 K (−100.07 °C) | 26.60 kPa (0.2625 atm) |

| Hydrogen | 13.84 K (−259.31 °C) | 7.04 kPa (0.0695 atm) |

| Hydrogen chloride | 158.96 K (−114.19 °C) | 13.9 kPa (0.137 atm) |

| Iodine[15] | 386.65 K (113.50 °C) | 12.07 kPa (0.1191 atm) |

| Isobutane[16] | 113.55 K (−159.60 °C) | 1.9481 × 10−5 kPa |

| Krypton | 115.76 K (−157.39 °C) | 74.12 kPa (0.7315 atm) |

| Mercury | 234.2 K (−39.0 °C) | 1.65 × 10−7 kPa |

| Methane | 90.68 K (−182.47 °C) | 11.7 kPa (0.115 atm) |

| Neon | 24.57 K (−248.58 °C) | 43.2 kPa (0.426 atm) |

| Nitric oxide | 109.50 K (−163.65 °C) | 21.92 kPa (0.2163 atm) |

| Nitrogen | 63.18 K (−209.97 °C) | 12.6 kPa (0.124 atm) |

| Nitrous oxide | 182.34 K (−90.81 °C) | 87.85 kPa (0.8670 atm) |

| Oxygen | 54.36 K (−218.79 °C) | 0.152 kPa (0.00150 atm) |

| Palladium | 1,825 K (1,552 °C) | 3.5 × 10−3 kPa |

| Platinum | 2,045 K (1,772 °C) | 2.0 × 10−4 kPa |

| Radon | 202 K (−71 °C) | 70 kPa (0.69 atm) |

| Sulfur dioxide | 197.69 K (−75.46 °C) | 1.67 kPa (0.0165 atm) |

| Titanium | 1,941 K (1,668 °C) | 5.3 × 10−3 kPa |

| Uranium hexafluoride | 337.17 K (64.02 °C) | 151.7 kPa (1.497 atm) |

| Water[4][5] | 273.16 K (0.01 °C) | 0.611657 kPa (0.00603659 atm) |

| Xenon | 161.3 K (−111.8 °C) | 81.5 kPa (0.804 atm) |

| Zinc | 692.65 K (419.50 °C) | 0.065 kPa (0.00064 atm) |

* Note: for comparison, typical atmospheric pressure is 101.325 kPa (1 atm).

See also

References

- 1 2 IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (1994) "Triple point".

- ↑ Definition of the kelvin at BIPM

- ↑ James Thomson (1873) "A quantitative investigation of certain relations between the gaseous, the liquid, and the solid states of water-substance," Proceedings of the Royal Society, 22 : 27-36. From a footnote on page 28: " … the three curves would meet or cross each other in one point, which I have called the triple point."

- 1 2 International Equations for the Pressure along the Melting and along the Sublimation Curve of Ordinary Water Substance W. Wagner, A. Saul and A. Pruss (1994), J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 23, 515.

- 1 2 Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications. D. M. Murphy and T. Koop (2005) Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 131, 1539.

- ↑ Carr, Michael H. (2007). The Surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-521-87201-4.

- ↑ Cengel, Yunus A.; Turner, Robert H. (2004). Fundamentals of thermal-fluid sciences. Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 78. ISBN 0-07-297675-6.

- ↑ See Butane (data page)

- ↑ See Chloroform (data page)

- ↑ See Ethanol (data page)

- ↑ See Formic acid (data page)

- ↑ Donnelly, Russell J.; Barenghi, Carlo F. (1998). "The Observed Properties of Liquid Helium at the Saturated Vapor Pressure". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 27 (6): 1217–1274. Bibcode:1998JPCRD..27.1217D. doi:10.1063/1.556028.

- 1 2 3 Hoffer, J. K.; Gardner, W. R.; Waterfield, C. G.; Phillips, N. E. (April 1976). "Thermodynamic properties of 4He. II. The bcc phase and the P-T and VT phase diagrams below 2 K". Journal of Low Temperature Physics. 23 (1): 63–102. Bibcode:1976JLTP...23...63H. doi:10.1007/BF00117245.

- ↑ See Hexafluoroethane (data page)

- ↑ Walas, S. M. (1990). Chemical Process Equipment – Selection and Design. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 639. ISBN 0-7506-7510-1.

- ↑ See Isobutane (data page)