Valine

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Valine | |||

| Other names

2-amino-3-methylbutanoic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 516-06-3 72-18-4 (L-isomer) 640-68-6 (D-isomer) | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:57762 | ||

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL43068 | ||

| ChemSpider | 6050 | ||

| DrugBank | DB00161 | ||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.703 | ||

| EC Number | 208-220-0 | ||

| 4794 | |||

| KEGG | D00039 | ||

| PubChem | 1182 | ||

| UNII | 4CA13A832H | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[1] | |||

| C5H11NO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 117.15 g·mol−1 | ||

| Density | 1.316 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 298 °C (568 °F; 571 K) (decomposition) | ||

| soluble | |||

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.32 (carboxyl), 9.62 (amino)[2] | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |||

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

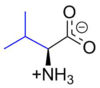

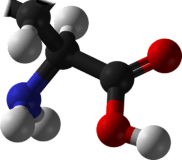

Valine (abbreviated as Val or V) encoded by the codons GUU, GUC, GUA, and GUG is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain isopropyl variable group, classifying it as a non-polar amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it and thus it must be obtained from the diet. Human dietary sources are any proteinaceous foods such as meats, dairy products, soy products, beans and legumes.

Along with leucine and isoleucine, valine is a branched-chain amino acid. In sickle-cell disease, valine substitutes for the hydrophilic amino acid glutamic acid in β-globin. Because valine is hydrophobic, the hemoglobin is prone to abnormal aggregation.

History and etymology

Valine was first isolated from casein in 1901 by Hermann Emil Fischer.[3] The name valine comes from valeric acid, which in turn is named after the plant valerian due to the presence of the acid in the roots of the plant.[4][5]

Nomenclature

According to IUPAC, carbon atoms forming valine are numbered sequentially starting from 1 denoting the carboxyl carbon, whereas 4 and 4' denote the two terminal methyl carbons.[6]

Biosynthesis

Valine is an essential amino acid, hence it must be ingested, usually as a component of proteins. It is synthesized in plants via several steps starting from pyruvic acid. The initial part of the pathway also leads to leucine. The intermediate α-ketoisovalerate undergoes reductive amination with glutamate. Enzymes involved in this biosynthesis include:[7]

- Acetolactate synthase (also known as acetohydroxy acid synthase)

- Acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase

- Dihydroxyacid dehydratase

- Valine aminotransferase

Synthesis

Racemic valine can be synthesized by bromination of isovaleric acid followed by amination of the α-bromo derivative[8]

- HO2CCH2CH(CH3)2 + Br2 → HO2CCHBrCH(CH3)2 + HBr

- HO2CCHBrCH(CH3)2 + 2 NH3 → HO2CCH(NH2)CH(CH3)2 + NH4Br

Valine and insulin resistance

Valine, as well as other branched-chain amino acids, are associated with insulin resistance, as higher levels of valine are observed in the blood of diabetic mice, rats, and humans.[9] Mice fed a valine free diet for one day have improved insulin sensitivity, and feeding of a valine free diet for one week significantly decreases blood glucose levels.[10] The valine catabolite 3-hydroxyisobutyrate promotes skeletal muscle insulin resistance in mice by stimulating fatty acid uptake into muscle and lipid accumulation.[11] In humans, a protein restricted diet lowers blood levels of valine and decreases fasting blood glucose levels.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Weast, Robert C., ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-569. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8.

- ↑ Dawson, R.M.C., et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ "valine". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ↑ "valine". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ↑ "valeric acid". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ↑ Jones, J. H., ed. (1985). Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins. Specialist Periodical Reports. 16. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-85186-144-9.

- ↑ Lehninger, Albert L.; Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2000), Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.), New York: W. H. Freeman, ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ↑ Marvel, C. S. (1940). "dl-Valine". Org. Synth. 20: 106.; Coll. Vol., 3, p. 848.

- ↑ Lynch, Christopher J.; Adams, Sean H. (2014-12-01). "Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 10 (12): 723–736. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.171. ISSN 1759-5037. PMC 4424797

. PMID 25287287.

. PMID 25287287. - ↑ Xiao, Fei; Yu, Junjie; Guo, Yajie; Deng, Jiali; Li, Kai; Du, Ying; Chen, Shanghai; Zhu, Jianmin; Sheng, Hongguang (2014-06-01). "Effects of individual branched-chain amino acids deprivation on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in mice". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 63 (6): 841–850. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2014.03.006. ISSN 1532-8600. PMID 24684822.

- ↑ Jang, Cholsoon; Oh, Sungwhan F.; Wada, Shogo; Rowe, Glenn C.; Liu, Laura; Chan, Mun Chun; Rhee, James; Hoshino, Atsushi; Kim, Boa (2016-04-01). "A branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes insulin resistance". Nature Medicine. 22 (4): 421–426. doi:10.1038/nm.4057. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 26950361.

- ↑ Fontana, Luigi; Cummings, Nicole E.; Arriola Apelo, Sebastian I.; Neuman, Joshua C.; Kasza, Ildiko; Schmidt, Brian A.; Cava, Edda; Spelta, Francesco; Tosti, Valeria (2016-06-21). "Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health". Cell Reports. 16: 520–30. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092. ISSN 2211-1247. PMC 4947548

. PMID 27346343.

. PMID 27346343.