Vergangenheitsbewältigung

Vergangenheitsbewältigung[1] (German: [fɛɐ̯ˈɡaŋn̩haɪtsbəˌvɛltɪɡʊŋ], "struggle to overcome the [negatives of the] past")[2] is a German term describing processes that since the late 20th century have become key in the study of post-1945 German literature, society, and culture.

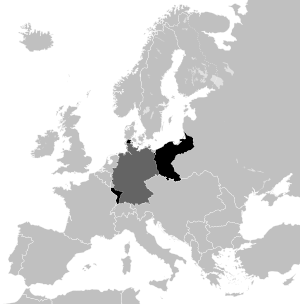

The German Duden lexicon defines Vergangenheitsbewältigung as "public debate within a country on a problematic period of its recent history—in Germany on National Socialism, in particular"[3][4]—where "problematic" refers to traumatic events that raise sensitive questions of collective culpability. In Germany, and originally, the term refers to embarrassment about and often remorse for Germans' complicity in the war crimes of the Wehrmacht, Holocaust, and related events of the early and mid-20th century, including World War II. In this sense, the word can refer to the psychic process of denazification. With the absorption into the current Federal Republic of Germany of East Germany since 1989 and the fall of the Soviet Union, Vergangenheitsbewältigung can also refer to coming to terms with the excesses and human rights abuses associated with that former Communist state.

Historical development

Vergangenheitsbewältigung describes the attempt to analyze, digest and learn to live with the past, in particular the Holocaust. The focus on learning is much in the spirit of philosopher George Santayana's oft-quoted observation that "those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it." As a technical term in English, it relates specifically to the atrocities committed during the Third Reich, when Adolf Hitler was in power in Germany, and to both historical and contemporary concerns about the extensive compromise and co-optation of many German cultural, religious, and political institutions by Nazism. The term therefore deals at once with the concrete responsibility of the German state (West Germany assumed the legal obligations of the Reich) and of individual Germans for what took place "under Hitler," and with questions about the roots of legitimacy in a society whose development of the Enlightenment collapsed in the face of Nazi ideology.

More recently, the term Vergangenheitsbewältigung has also been used in the former East Germany to refer to the process of working through the brutalities of Communist institutions.

After denazification

Historically, Vergangenheitsbewältigung often is seen as the logical "next step," after a denazification driven at first under Allied Occupation and then by the Christian Democratic Union government of Konrad Adenauer. It dates from the late 1950s and early 1960s, roughly the period in which the work of the Wiederaufbau (reconstruction) became less absorbing and urgent. Having replaced the institutions and power structures of Nazism, the aim of liberal Germans was to deal with the guilt of recent history. Vergangenheitsbewältigung is characterised in part by learning from the past. This includes honestly admitting that such a past did indeed exist, attempting to remedy as far as possible the wrongs committed, and attempting to move on from that past.

Role of churches and schools

The German churches, of which only a minority played a significant role in the resistance to Nazism, have led the way in this process. They have developed a specifically German post-war theology of repentance. At the regular mass church rallies, the Lutheran Kirchentag and the Catholic Katholikentag, for example, have developed this theme as a leitmotiv of Christian youth.

Vergangenheitsbewältigung has been expressed by the society through its schools, where in most German states the centrally-written curriculum provides each child with repeated lessons on different aspects of Nazism in German history, politics and religion classes from the fifth grade onwards, and related to their maturity. Associated school trips may have destinations of concentration camps. Jewish Holocaust survivors are often invited to schools as guest speakers, though the passage of time limits these opportunities as their generation has aged.

In philosophy

In philosophy, Theodor Adorno's writings include the lecture "Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit?" (What is meant by 'working through the past'?), a subject related to his thinking of "after Auschwitz" in his later work. He delivered the lecture on November 9, 1959 at a conference on education held in Wiesbaden.[5] Writing in the context of a new wave of anti-Semitic attacks against synagogues and Jewish community institutions occurring in West Germany at that time, Adorno rejects the contemporary catch phrase 'working through the past' as misleading. He says that it masks a denial, rather than signifying the kind of critical self-reflection that Freudian theory called for in order to 'come to terms' with the past.[5]

Adorno's lecture is often seen as consisting in part of a variably implicit and explicit critique of the work of Martin Heidegger, whose formal ties to the Nazi party are well-known. Heidegger, distinct from his role in the Party during the Third Reich, attempted to provide a historical conception of Germania as a philosophical thought of German origin and destiny (later he would speak of "the West"). Alexander Garcia Düttman's "Das Gedächtnis des Denkens: Versuch über Heidegger und Adorno" ("The Memory of Thought: an Essay on Heidegger and Adorno," translated by Nicholas Walker) attempts to treat the philosophical value of these seemingly opposed and certainly incompatible terms "Auschwitz" and "Germania" in the philosophy of both men. It does not simply compare them.

The cultural sphere

In the cultural sphere, the term Vergangenheitsbewältigung is associated with a movement in German literature, characterised by such authors as Günter Grass and Siegfried Lenz. Lenz's novel Deutschstunde and Grass's Danziger Trilogie both deal with childhoods under Nazism.

The erection of public monuments to Holocaust victims has been a tangible commemoration of Germany's Vergangenheitsbewältigung. Concentration camps, such as Dachau, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and Flossenbürg, are open to visitors as memorials and museums. Most towns have plaques on walls marking the spots where particular atrocities took place.

When the seat of government was moved from Bonn to Berlin in 1999, an extensive "Holocaust memorial", designed by architect Peter Eisenman, was planned as part of the extensive development of new official buildings in the district of Berlin-Mitte; it was opened on 10 May 2005. The informal name of this memorial, the Holocaust-Mahnmal, is significant. It does not translate easily: "Holocaust Cenotaph" would be one sense, but the noun Mahnmal, which is distinct from the term Denkmal (typically used to translate "memorial") carries the sense of "admonition," "urging," "appeal," or "warning," rather than "remembrance" as such. The work is formally known as das Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas (English translation, "The Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe"). Some controversy attaches to it precisely because of this formal name and its exclusive emphasis on Jewish victims. As Eisenman acknowledged at the opening ceremony, "It is clear that we won't have solved all the problems — architecture is not a panacea for evil — nor will we have satisfied all those present today, but this cannot have been our intention."

Actions of other European countries

In Austria, ongoing arguments about the nature and significance of the Anschluss, and unresolved disputes about legal expressions of obligation and liability, have led to very different concerns, and to a far less institutionalized response by the government. Since the late 20th century, observers and analysts have expressed concerns about the ascent of "Haiderism."[lower-alpha 1]

Poland has maintained a museum, archive, and research centre at Oświęcim, better known by its German name of Auschwitz, since a July 2, 1947 act of the Polish Parliament. In the same year, Czechoslovakia established what was known as the "National Suffering Memorial" and later as the Terezín memorial in Terezín, Czech Republic. This site during the Holocaust was known as the concentration camp of Theresienstadt. In the context of varying degrees of Communist orthodoxy in both countries during the period of Soviet domination of Eastern Europe through much of the late 20th century, historical research into the Holocaust was politicised to varying degrees. Marxist doctrines of class struggle were often overlaid onto generally received histories, which tended to exclude both acts of collaboration and indications of abiding antisemitism in these nations.

The advance of the Einsatzgruppen, Aktion Reinhardt, and other significant events in the Holocaust did not happen in the Third Reich proper (or what is now the territory of the Federal Republic). The history of the memorials and archives which have been erected at these sites in eastern Europe is associated with the Communist regimes that ruled these areas for more than four decades after World War II. The Nazis promoted an idea of an expansive German nation extending into territories where ethnic Germans had previously settled. They invaded and controlled much of Central and Eastern Europe, unleashing violence against various Slavic groups, as well as Jews, Communists, homosexuals, prisoners of war, and so-called partisans. There were millions of victims in addition to Jews. After the war, the eastern European nations expelled German settlers as well as long settled ethnic Germans (the Volksdeutsche) as a reaction to the Reich's attempt to claim the eastern lands on behalf of ethnic Germans.

Czechoslovakia and Poland described their process as lustration.

Analogous processes elsewhere in the world

In some of its aspects, Vergangenheitsbewältigung can be compared to the attempts of other democratic countries to raise consciousness and come to terms with earlier periods of governmental and social abuses, such as the South African process of truth and reconciliation following the period of apartheid and suppression of African groups seeking political participation and freedom from white oppression.

Some comparisons have been made with the Soviet process of glasnost, though this was less focused on the past than achieving a level of open criticism necessary for progressive reform to take place. (It generally assumed that the Communist Party monopoly on power would be maintained.) Since the late 20th century and the fall of the Soviet Union, the continuing efforts in nations of eastern Europe and the independent states of the former Soviet Union to reinterpret the communist past and its abuses is sometimes referred to as a post-socialist Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

In popular culture

Political satirist Roy Zimmerman has a song called "Vergangenheitsbewaeltigung," on his album Security. [6]

See also

- Functionalism versus intentionalism

- Bottom-up approach of the Holocaust

- Nazi foreign policy debate

- Historiography of Germany

- Historikerstreit

- Sonderweg

- Victim theory, a theory that Austria was a victim of Nazism following the Anschluss

- Transitional justice

- Transitional Justice Institute

- Truth-seeking

- Never Again

- Never Forget

Notes

- ↑ Haider's growing popularity was protested by many Austrians as proto- or neo-fascism after electoral successes in the Austrian legislative election of 1999 and his entry into coalition government with the Austrian People's Party.

References

- ↑ A compound of die Vergangenheit "the past" and Bewältigung "the overcoming of problems", often used in psychological contexts for coming to terms with repressed and incriminating mental injuries and guilt.

- ↑ Collins German-English Dictionary: Vergangenheitsbewältigung

- ↑

- ↑ "Auseinandersetzung einer Nation mit einem problematischen Abschnitt ihrer jüngeren Geschichte, in Deutschland besonders mit dem Nationalsozialismus"

- 1 2 Boos, Sonja (2014). Introduction to Theodor W. Adorno's "Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit" (The Meaning of Working through the Past). A media supplement to: Boos, Speaking the Unspeakable in Postwar Germany: Toward a Public Discourse on the Holocaust. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. The website (under the banner of the "Signale" book series on modern German literature and culture) includes the audio recording of Adorno's lecture, along with links to the German text and an English translation.

- ↑ Roy Zimmerman - Lyrics - Security - Vergangenheitsbewaeltigung

Sources

- Frei, Norbert; Vergangenheitspolitik. Die Anfänge der Bundesrepublik und die NS-Vergangenheit. Munich: C.H. Beck, 1996. [In English as Adenauer's Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration. New York: Columbia University Press]

- Geller, Jay Howard; Jews in Post-Holocaust Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Herf, Jeffrey; Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the Two Germanys. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Maier, Charles S.; The Unmasterable Past: History, Holocaust, and German National Identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- Maislinger, Andreas; Coming to Terms with the Past: An International Comparison. In Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Identity. Cross National and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Russel F. Farnen. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 2004.

- Moeller, Robert G.; War Stories: The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Moeller, Robert G. (ed.); West Germany Under Construction: Politics, Society and Culture in the Adenauer Era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

- Pross, Christian; Paying for the Past: The Struggle over Reparations for Surviving Victims of the Nazi Terror. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Transitional Justice and Dealing with the Past", in: Berghof Glossary on Conflict Transformation. 20 notions for theory and practice. Berlin: Berghof Foundation, 2012.