Vicente Guerrero

| Vicente Guerrero | |

|---|---|

|

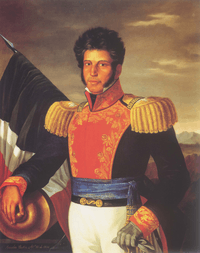

A half-length, posthumous portrait by Anacleto Escutia (1850) | |

2nd President of Mexico | |

|

In office April 1, 1829 – December 17, 1829 | |

| Vice President | Anastasio Bustamante |

| Preceded by | Guadalupe Victoria |

| Succeeded by | José María Bocanegra |

| Member of the Supreme Executive Power | |

|

In office April 1, 1823 – October 10, 1824 | |

| Preceded by |

Constitutional Monarchy Agustín I |

| Succeeded by |

Federal Republic Guadalupe Victoria |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña August 10, 1782 Tixtla, Guerrero, New Spain |

| Died |

February 14, 1831 (aged 48) Cuilapan, Oaxaca, Mexico |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | María de Guadalupe Hernández |

| Children | María de los Dolores Guerrero Hernández |

| Profession |

Military Officer Politician |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Mexican Army |

| Years of service | 1810–1821 |

| Rank |

General Lieutenant colonel Captain |

| Commands | Mexican War of Independence |

| Battles/wars |

Battle of El Veladero Siege of Cuautla Battle of Izúcar Siege of Huajuapan de León Battle of Zitlala Capture of Oaxaca Siege of Acapulco |

Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña (Spanish: [biˈsente raˈmoŋ ɡeˈreɾo salˈdaɲa]; August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as President of Mexico, coming to power in a coup. He was of Afro-Mestizo descent, championed the cause of Mexico's common people, and abolished slavery during his brief term as president.[1] His execution in 1831 by the conservative government that ousted him in 1829 was a shock to the nation.[2]

Early life

Guerrero was born in Tixtla, a town 100 kilometers inland from the port of Acapulco, in the Sierra Madre del Sur; his parents were María de Guadalupe Saldaña, of African descent and Pedro Guerrero, a Mestizo.[3][4][5] Guerrero was tall and robust, and dark complected, and he was at times called El Negro.[6] The region where he grew up had a large concentration of indigenous groups, and as a young man he was more conversant in the local language than Spanish.[7][8] His father's family included landlords, rich farmers and traders with broad business connections in the south, members of the Spanish militia and gun and cannon makers. In his youth, he worked for his father's freight business that used mules for transport. His travels took him to different parts of Mexico where he heard of the ideas of independence.

Vicente's father, Pedro, supported Spanish rule, whereas his uncle, Diego Guerrero, had an important position in the Spanish militia. As an adult, Vicente was opposed to the Spanish colonial government. When his father asked him for his sword in order to present it to the viceroy of New Spain as a sign of goodwill, Vicente refused, saying, "The will of my father is for me sacred, but my Fatherland is first." "Mi patria es primero" is now the motto of the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, named in honor of the revolutionary. Guerrero enlisted in José María Morelos's insurgent army of the south in December 1810.

Marriage and family

He married María de Guadalupe Hernández; their daughter María de los Dolores Guerrero Hernández married Mariano Riva Palacio, who was the defense lawyer of Maximilian I of Mexico in Querétaro, and was the mother of late nineteenth-century intellectual Vicente Riva Palacio.

Career as an insurgent, 1810-21

In 1810 Guerrero joined in the early revolt against Spain, first fighting in the forces of secular priest José María Morelos. Morelos described him as "A young man with bronzed (N.B. "broncínea", lit. bronze-colored, swarthy), tall and strong (N.B. "fornido", strapping, muscular), aquiline nose, bright and light-colored eyes and big sideburns."[9] When the War of Independence began, Guerrero was working as a gunsmith in Tixtla. He joined the rebellion in November 1810 and enlisted in a division that independence leader Morelos had organized to fight in southern Mexico. Guerrero distinguished himself in the battle of Izúcar, in February 1812, and had achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel when Oaxaca was claimed by rebels in November 1812.[7] Initial victories by Morelos's forces faltered and Morelos himself was captured and executed in December 1815. Guerrero joined forces with Guadalupe Victoria and Isidoro Montes de Oca, taking the position of "Commander in Chief" of the rebel troops. In 1816, the royal government under Viceroy Apodaca sought to end the insurgency, offering amnesty. Guerrero's father carried one appeal for his son to surrender, but Guerrero refused. He remained the only major rebel leader still at large, keeping the rebellion going through an extensive campaign of guerrilla warfare. He won victories at Ajuchitán, Santa Fe, Tetela del Río, Huetamo, Tlalchapa and Cuautlotitlán, regions of southern Mexico that were very familiar to him.

.png)

Hoping to extinguish the rebellion, the royal government sent Agustín de Iturbide against Guerrero's forces. Guerrero was victorious against Iturbide, who realized there was a military stalemate. Guerrero appealed to Iturbide to abandon his royalist loyalty and join the fight for independence.[10] Events in Spain had changed in 1820, with Spanish liberals ousting Ferdinand VII and imposing the liberal constitution of 1812 that the king had repudiated. Conservatives in Mexico, including the Catholic hierarchy began to conclude that continued allegiance to Spain would undermine their position, and opted for independence in order to maintain their control. Guerrero's appeal to join the forces for independence was successful. Guerrero and Iturbide allied under the Plan de Iguala and their forces merged as the Army of the Three Guarantees.

The Plan of Iguala proclaimed independence, called for a constitutional monarchy and the continued place of the Roman Catholic Church, and abolished the formal casta system of racial classification. Clause 12 was incorporated into the plan. It read: All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.[11][12] The Army of the Three Guarantees marched triumphantly into Mexico City in September 27, 1821.[13]

Mexican Empire, 1822-23

Agustín de Iturbide was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico by Congress. In January of 1823, Guerrero, along with Nicolás Bravo, rebelled against Iturbide, returning to southern Mexico to raise rebellion, according some assessments because their careers had been blocked by the emperor. Their stated objectives were to restore the Constituent Congress. Guerrero and Bravo were defeated by Iturbide's forces at Almolongo (now in the State of Guerrero) less than a month later.[14] When Iturbide's imperial government collapsed in 1823, Guerrero was named one of Constituent Congress's ruling triumvirate.[15]

1828 Presidential Election

Guerrero was a liberal by conviction, and active in the York Rite Masons, established in Mexico after independence by Joel Roberts Poinsett, the U.S. diplomatic representative to the newly independent Mexico. The Scottish Rite Masons had been established before independence. Following independence the Yorkinos appealed to a broad range of Mexico's populace, as opposed to the Scottish Rite Masons, who were a bulwark of conservatism, and in the absence of established political parties, the rival groups of Masons functioned as political organizations. Guerrero had a large following among urban Yorkinos, who were mobilized during the 1828 election campaign and afterwards, in the ouster of the president-elect.[16]

In 1828, when the four-year term of the first president of the republic, Guadalupe Victoria, came to an end, but unlike the first presidential election and the president serving his full term, the one in 1828 was highly partisan. Guerrero's supporters included federalist liberals, members of the radical wing of the York Rite Freemasons. General Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the September 1828 election to succeed Guadalupe Victoria, with Guerrero coming in second and Anastasio Bustamante, third through indirect election of Mexico's state legislatures. Gómez Pedraza was the candidate of the "Impartials", composed of Yorkinos concerned about the radicalism of Guerrero and Scottish Rite Masons (Escocés), who sought a new political party. Among those who were Impartials were distinguished federalist Yorkinos Valentín Gómez Farías and Miguel Ramos Arizpe.[17] The U.S. diplomatic representative in Mexico, Joel Roberts Poinsett was enthusiastic about Guerrero's candidacy, writing

"....A man who is held up as ostensible head of the party, and who will be their candidate for the next presidency, is General Guerrero, one of the most distinguished chiefs of the revolution. Guerrero is uneducated, but possesses excellent natural talents, combined with great decision of character and undaunted courage. His violent temper renders him difficult to control, and therefore I consider Zavala's presence here indispensably necessary, as he possesses great influence over the general."— Joel R. Poinsett, US minister for Mexico (i.e. Ambassador), about the character of Vicente Guerrero

Guerrero himself did not leave an abundant written record, but some of his speeches survive.

"A free state protects the arts, industry, science and trade; and the only prizes virtue and merit: if we want to acquire the latter, let's do it cultivating the fields, the sciences, and all that can facilitate the sustenance and entertainment of men: let's do this in such a way that we will not be a burden for the nation, just the opposite, in a way that we will satisfy her needs, helping her to support her charge and giving relief to the distraught of humanity: with this we will also achieve abundant wealth for the nation, making her prosper in all aspects."— Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña, Speech to his compatriots

Two weeks after the September 1 election, Antonio López de Santa Anna rose in rebellion in support of Guerrero. As governor of the strategic state of Veracruz and former general in the war of independence, Santa Anna was a powerful figure in the early republic, but he was unable to persuade the state legislature to support Guerrero in the indirect elections. Santa Anna resigned the governorship and led 800 troops loyal to him in capturing the fortress of Perote, near Jalapa. He issued a political plan there calling for the nullification of Gómez Pedraza's election and the declaration of Guerrero as president.[18]

In November 1828 in Mexico City, Guerrero supporters took control of the Acordada, a former prison transformed into an armory, and days of fighting occurred in the capital. President-elect Gómez Pedraza had not yet taken office and at this juncture he resigned and soon went into exile in England.[19] With the resignation of the president-elect and the ineffective rule of the sitting president, civil order dissolved. On 4 December 1828, a riot broke out in the Zócalo and the Parián market, where luxury goods were sold, was looted. Order was restored within a day, but elites in the capital were alarmed at the violence of the popular classes and the huge property losses.[20][21] With the resignation of Gómez Pedrazo, and Guerreros's cause backed by Santa Anna's forces and the powerful liberal politician Lorenzo de Zavala, Guerrero became president. Guerrero took office as president, with Bustamante, a conservative, becoming vice president. One scholar sums up Guerrero's situation, "Guerrero owed the presidency to a mutiny and a failure of will on the part of [President] Guadalupe Victoria...Guerrero was to rule as president with only a thin layer of support."[22]

Presidency April - December 1829

Liberal folk hero of the independence insurgency Guerrero became president on 1 April 1829, with conservative Anastasio Bustamante as his vice president. For some of Guerrero's supporters, a visibly mixed-race man from Mexico's periphery becoming president of Mexico was a step toward in what one 1829 pamphleteer called "the reconquest of this land by its legitimate owners" and called Guerrero "that immortal hero, favorite son of Nezahualcoyotzin", the famous prehispanic ruler of Texcoco.[23] Creole elites (American-born whites of Spanish heritage) were alarmed by Guerrero as president, a group that Lorenzo de Zavala called "the new Mexican aristocracy".[24]

Guerrero set about creating a cabinet of liberals, but his government already encountered serious problems, including its very legitimacy since president-elect Gómez Pedraza had resigned under pressure, such that some traditional federalists leaders in some states, who might have supported Guerrero, did not do so. The national treasury was empty and future revenues were already liened. Spain continued to deny Mexico's independence and threatened reconquest.[25]

Guerrero called for public schools, land title reforms, industry and trade development, and other programs of a liberal nature. As president, Guerrero championed the causes of the racially oppressed and economically oppressed. He ordered an immediate abolition of slavery on September 16 of 1829. In central Mexico, there were few black slaves, so that the gesture was largely symbolic, but in the Mexican state of Texas, where Anglo-American slave-holding southerners were colonizing, the decree went against their economic interests.[26] and emancipation of all slaves. Initially, Anglo-American Stephen F. Austin, colonizer in Texas, was enthusiastic about the Mexican government.

"This is the most liberal and munificent Government on earth to emigrants – after being here one year you will oppose a change even to Uncle Sam"— Stephen Fuller Austin, 1829, letter to his sister describing Guerrero's Government of Mexico (and Texas)

During Guerrero's presidency, the Spanish tried to reconquer Mexico, but they failed, being defeated at the Battle of Tampico.

Ouster, Capture and Execution, December 1829 - February 1831

Guerrero was deposed in a rebellion under Vice-President Anastasio Bustamante that began on 4 December 1829. Guerrero left the capital to fight in the south, but was deposed by the Mexico City garrison in his absence on 17 December 1829. Guerrero had returned to the region of southern Mexico where he had fought during the war of independence. Elites in Mexico City feared Guerrero's appeal to mixed-race Mexicans and Indians. Bustamante feared the claim that Guerrero was descended from Aztec royalty would bolster his appeal to Indians. "It is greatly to be feared that once the Indians were aroused by Guerrero they would form a party that would lead to caste [race] war."[27]

Open warfare between Guerrero and his opponent in the region Nicolás Bravo was fierce. Bravo had been a royalist officer and Guerrero was an insurgent hero. Bravo controlled the highlands of the region, including the town of Guerrero's birth, Tixtla. Guerrero had strength in the hot coastal regions of the Costa Grande and Tierra Caliente, with mixed race populations that had been mobilized during the insurgency for independence. Bravo's area had a mixed population, but politically was dominated by whites. The conflict in the south occurred for all of 1830, as conservatives consolidated power in Mexico City.[28]

The war in the south might have continued even longer, but ended in what one historian has called "the most shocking single event in the history of the first republic: the capture of Guerrero in Acapulco through an act of betrayal and his execution a month later."[28] Guerrero controlled Mexico's principal Pacific coast port of Acapulco. An Italian merchant ship captain, Francisco Picaluga, approached the conservative government in Mexico City with a proposal to lure Guerrero onto his ship and take him prisoner for the price of 50,000 pesos, a fortune at the time. Picaluga invited Guerrero on board for a meal on 14 January 1831. Guerrero and a few aids were taken captive and Picaluga sailed to the port of Huatulco, where Guerrero was turned over to federal troops. Guerrero was taken to Oaxaca City and summarily tried by a court-martial.[29]

His capture was welcomed by conservatives and some state legislatures, but the legislatures of Zacatecas and Jalisco tried to prevent Guerrero's execution. The government's 50,000 peso payment to Picaluga was exposed in the liberal press. Despite pleas for his life, Guerrero was executed by firing squad in Cuilapam on 14 February 1831. His death did mark the dissolution of the rebellion in southern Mexico, but those politicians involved in his execution paid a lasting price to their reputations.[29]

Many Mexicans saw Guerrero as the "martyr of Cuilapam" and his execution was deemed by the liberal newspaper El Federalista Mexicano "judicial murder". The two conservative cabinet members considered most culpable for Guerrero's execution, Lucas Alamán and Secretary of War José Antonio Facio, "spent the rest of their lives defending themselves from the charge that they were responsible for the ultimate betrayal in the history of the first republic, that is, that they had arranged not just for the service of Picaluga's ship but specifically for his capture of Guerrero."[28]

Historian Jan Bazant speculates as to why Guerrero was executed rather than sent into exile, as Iturbide had been, as well as Antonio López de Santa Anna, and long-time dictator of late-nineteenth century Mexico, Porfirio Díaz. "The clue is provided by Zavala who, writing several years later, noted that Guerrero was of mixed blood and that the opposition to his presidency came from the great landowners, generals, clerics and Spaniards resident in Mexico...Guerrero's execution was perhaps a warning to men considered as socially and ethnically inferior not to dare to dream of becoming president."[30]

Honors were conferred on surviving members of Guerrero's family, and a pension was paid to his widow. In 1842, Vicente Guerrero's remains were exhumed and returned to Mexico City for reinterment. He is known for his political discourse promoting equal civil rights for all Mexican citizens. He has been described as the "greatest man of color" to ever live.[31]

Legacy

Guerrero is a Mexican national hero. The state of Guerrero is named in his honour. Several towns in Mexico are named in honor of this famous general, including Vicente Guerrero in Baja California.

Statue in honor of Vicente Guerrero in Nuevo Laredo

Statue in honor of Vicente Guerrero in Nuevo Laredo Monument to Vicente Guerrero in Mexico City.

Monument to Vicente Guerrero in Mexico City.

See also

References

- ↑ Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade, 1823-1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987. p. 119.

- ↑ Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821-1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998, 242.

- ↑ Vincent, Theodore G. (2001). The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University of Florida Press. pp. 8–12.

- ↑ Sprague, William Forrest (1939). Vicente Guerrero, Mexican Liberator: A Study in Patriotism. R. R. Donnelley - Mexico. p. 42.

- ↑ "Research Reveals the African-Indigenous Heritage of Mexican President Vicente Guerrero | Pathways to Freedom in the Americas". Mlktaskforcemi.org. 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- ↑ Richmond, Douglas W. "Vicente Guerrero" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 616.

- 1 2 Richmond, "Vicente Guerrero", p. 616.

- ↑ Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade, 1823-1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987. p. 163.

- ↑ Physical description of Vicente Guerrero Saldaña by José María Morelos y Pavón, 1811.

- ↑ Richmond, "Vicente Guerrero", pp. 616–17.

- ↑ Vincent, Theodore G. (2001). The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University of Florida Press. pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Richmond, "Vicente Guerrero", p. 617.

- ↑ Henderson, Timothy J. (2009). The Mexican Wars for Independence. Hill and Wang. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8090-6923-1.

- ↑ Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821-1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998. p. 105.

- ↑ Anna, Forging Mexico, pp. 111–12.

- ↑ Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade, 1823-1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987, pp. 87–111, 155–57.

- ↑ Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821-1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998. p. 207.

- ↑ Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 218.

- ↑ Katz, William Loren. "The Majestic Life of President Vicente Ramon Guerrero". William Loren Katz. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Arrom, Silvia. "Popular Politics in Mexico City: The Parián Riot, 1828". Hispanic American Historical Review 68, no. 2 (May 1988): 245–68.

- ↑ Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821-1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998, 219–20.

- ↑ C. Green, Stanley. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade, 1823-1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987. pp. 159–161.

- ↑ Quoted in Hale, Charles A. Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora. New Haven: Yale University Press 1968. p. 224.

- ↑ Hale, Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora, p. 224.

- ↑ Green, The Mexican Republic, pp. 162–63.

- ↑ Sprague, William Forrest. "Coahuila y Texas Under President Vicente Guerrero". TAMU. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Quoted in Brading, D. A. The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991. p. 642.

- 1 2 3 Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 241.

- 1 2 Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 242.

- ↑ Bazant, Jan. "The Aftermath of Independence" in Mexico Since Independence. Leslie Bethell, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991. p. 12.

- ↑ Vincent, Theodore G. (2001). The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University of Florida Press. p. 81.

Further reading

- Anna, Timothy E. The Mexican Empire of Iturbide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1990.

- Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821-1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998.

- Arrom, Silvia. "Popular Politics in Mexico City: The Parián Riot, 1828". Hispanic American Historical Review 68, no. 2 (May 1988): 245-68.

- Avila, Alfredo. "La presidencia de Vicente Guerrero", in Will Fowler, ed., Gobernantes mexicanos, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2008, t. I, p. 27-49. ISBN 978-968-16-8369-6.

- Bazant, Jan. "From Independence to the Liberal Republic, 1821-67" in Mexico since Independence, edited by Leslie Bethelll. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- González Pedrero, Enrique. País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna. Volumen II : La sociedad de fuego cruzado 1829-1836 : Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-6377-2.

- Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade 1823-1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987.

- Guardino, Peter F. Peasants, Politics, and the Formation of Mexico's National State: Guerrero 1800-1857. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1996.

- Hale, Charles A. Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora. New Haven: Yale University Press 1968.

- Hamnett, Brian. Roots of Insurgency: Mexican Regions, 1750-1824. New York: Cambridge University Press 1986.

- Harrell, Eugene Wilson. "Vicente Guerrero and the Birth of Modern Mexico, 1821-1831". PhD dissertation, Tulane University 1976.

- Huerta-Nava, Raquel (2007). El Guerrero del Alba. La vida de Vicente Guerrero. Grijalbo. ISBN 978-970-780-929-1.

- Ramírez Fentanes, Luis. Vicente Guerrero, Presidente de México. Mexico City: Comisión de Historia Militar 1958.

- Richmond, Douglas W. "Vicente Guerrero" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 616-18.

- Sims, Harold. The Expulsion of Mexico's Spaniards, 1821-1836. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1990.

- Sprague, William. Vicente Guerrero, Mexican Liberator: A Study in Patriotism. Chicago: Donnelley 1939.

- Vincent, Theodore G. The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University of Florida Press 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vicente Guerrero. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vicente Guerrero |

- Biografía de Vicente Guerrero en el Portal Oficial del Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero

- Vicente Guerrero: An Inventory of His Collection at the Benson Latin American Collection

- Vicente Guerrero on Mexconnect.com

- Guerrero on gob.mex/kids

- Letters about Vicente Guerrero hosted by the Portal to Texas History

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Guadalupe Victoria |

President of Mexico 1 April – 17 December 1829 |

Succeeded by José María Bocanegra |