Walker Evans

| Walker Evans | |

|---|---|

|

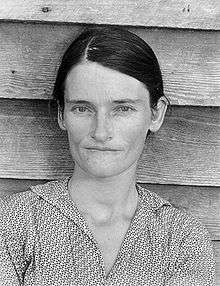

Walker Evans in 1937 | |

| Born |

November 3, 1903 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

April 10, 1975 (aged 71) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable work |

American Photographs (1938) Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) Many Are Called (1966) |

Walker Evans (November 3, 1903 – April 10, 1975) was an American photographer and photojournalist best known for his work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documenting the effects of the Great Depression. Much of Evans's work from the FSA period uses the large-format, 8x10-inch camera. He said that his goal as a photographer was to make pictures that are "literate, authoritative, transcendent".[1] Many of his works are in the permanent collections of museums and have been the subject of retrospectives at such institutions as The Metropolitan Museum of Art or George Eastman House.[2]

Biography

Early life

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, to Jessie (née Crane) and Walker,[3] Walker Evans came from an affluent family. His father was an advertising director. He spent his youth in Toledo, Chicago, and New York City. He attended The Loomis Institute and Mercersburg Academy[4] before graduating from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, in 1922. He studied French literature for a year at Williams College, spending much of his time in the school's library, before dropping out. After spending a year in Paris in 1926, he returned to the United States to join the edgy literary and art crowd in New York City. John Cheever, Hart Crane, and Lincoln Kirstein were among his friends. He was a clerk for a stockbroker firm in Wall street from 1927 to 1929.[5]

Evans took up photography in 1928[1] around the time he was living in Ossining, New York.[6] His influences included Eugène Atget and August Sander.[7] In 1930, he published three photographs (Brooklyn Bridge) in the poetry book The Bridge by Hart Crane. In 1931, he made a photo series of Victorian houses in the Boston vicinity sponsored by Lincoln Kirstein.

In May and June 1933, Evans took photographs in Cuba on assignment for Lippincott, the publisher of Carleton Beals' The Crime of Cuba (1933), a "strident account" of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. There Evans drank nightly with Ernest Hemingway, who loaned him money to extend his two-week stay an additional week. His photographs documented street life, the presence of police, beggars and dockworkers in rags, and other waterfront scenes. He also helped Hemingway acquire photos from newspaper archives that documented some of the political violence Hemingway described in To Have and Have Not (1937). Fearing that his photographs might be deemed critical of the government and confiscated by Cuban authorities, he left 46 prints with Hemingway. He had no difficulties when returning to the United States, and 31 of his photos appeared in Beals' book. The cache of prints left with Hemingway was discovered in Havana in 2002 and exhibited at an exhibition in Key West.[8][9]

Depression-era photography

In 1935, Evans spent two months at first on a fixed-term photographic campaign for the Resettlement Administration (RA) in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. From October on, he continued to do photographic work for the RA and later the Farm Security Administration (FSA), primarily in the Southern United States.

In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, he and writer James Agee were sent by Fortune magazine on assignment to Hale County, Alabama, for a story the magazine subsequently opted not to run. In 1941, Evans's photographs and Agee's text detailing the duo's stay with three white tenant families in southern Alabama during the Great Depression were published as the groundbreaking book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Its detailed account of three farming families paints a deeply moving portrait of rural poverty. The critic Janet Malcolm notes that as in the earlier Beals' book there was a contradiction between a kind of anguished dissonance in Agee's prose and the quiet, magisterial beauty of Evans's photographs of sharecroppers.[10]

The three families headed by Bud Fields, Floyd Burroughs and Frank Tingle, lived in the Hale County town of Akron, Alabama, and the owners of the land on which the families worked told them that Evans and Agee were "Soviet agents," although Allie Mae Burroughs, Floyd's wife, recalled during later interviews her discounting that information. Evans's photographs of the families made them icons of Depression-Era misery and poverty. In September 2005, Fortune revisited Hale County and the descendants of the three families for its 75th anniversary issue.[11] Charles Burroughs, who was four years old when Evans and Agee visited the family, was "still angry" at them for not even sending the family a copy of the book; the son of Floyd Burroughs was also reportedly angry because the family was "cast in a light that they couldn't do any better, that they were doomed, ignorant".[11]

Evans continued to work for the FSA until 1938. That year, an exhibition, Walker Evans: American Photographs, was held at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. This was the first exhibition in the museum devoted to the work of a single photographer. The catalogue included an accompanying essay by Lincoln Kirstein, whom Evans had befriended in his early days in New York.

In 1938, Evans also took his first photographs in the New York subway with a camera hidden in his coat. These would be collected in book form in 1966 under the title Many are Called. In 1938 and 1939, Evans worked with and mentored Helen Levitt.

Evans, like such other photographers as Henri Cartier-Bresson, rarely spent time in the darkroom making prints from his own negatives. He only very loosely supervised the making of prints of most of his photographs, sometimes only attaching handwritten notes to negatives with instructions on some aspect of the printing procedure.

Later work

Evans was a passionate reader and writer, and in 1945 became a staff writer at Time magazine. Shortly afterward he became an editor at Fortune magazine through 1965. That year, he became a professor of photography on the faculty for Graphic Design at the Yale University School of Art.

In one of his last photographic projects, Evans completed a black and white portfolio of Brown Brothers Harriman & Co.'s offices and partners for publication in "Partners in Banking," published in 1968 to celebrate the private bank's 150th anniversary.[12] In 1973 and 1974, he also shot a long series with the then-new Polaroid SX-70 camera, after age and poor health had made it difficult for him to work with elaborate equipment.

The first definitive retrospective of his photographs, which "individually evoke an incontrovertible sense of specific places, and collectively a sense of America," according to a press release, was on view at New York's Museum of Modern Art in early 1971. Selected by John Szarkowski, the exhibit was titled simply Walker Evans.[13]

Death and legacy

| |

|

|

Evans died at his home in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1975.[14]

In 1994, The Estate of Walker Evans handed over its holdings to New York City's The Metropolitan Museum of Art.[15] The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the sole copyright holder for all works of art in all media by Walker Evans. The only exception is a group of approximately 1,000 negatives in collection of the Library of Congress which were produced for the Resettlement Administration (RA) / Farm Security Administration (FSA). Evans's RA / FSA works are in the public domain.[16]

In 2000, Evans was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame[17][18]

References

- 1 2 Archived March 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Walker Evans, by Jeff L. Rosenheim, Maria Morris Hambourg, Douglas Eklund, Mia Fineman (Princeton University Press, 2000) ISBN 0-691-05078-3, ISBN 978-0-691-05078-2

- ↑ "Walker Evans Dies; Artist With Camera", The New York Times, April 11, 1975

- ↑ "Walker Evans by James R. Mellow". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ↑ Petruck, Peninah R. (1979). The Camera Viewed: Writings on Twentieth-Century Photography. E. P. Dutton.

- ↑ "Walker Evans in Ossining". Ossining.org. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Peter Galassi, Walker Evans & Company. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Estrada, Alfredo José (2007). Havana: An Autobiography. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 187, 193–95, 266n. Estrada mistakenly identifies Beals' book as The Crimes of Cuba.

- ↑ Beals, Carleton (1933). The Crime of Cuba. New York: Lippincott.

- ↑ Malcolm, Janet (1980). Diana & Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography.

- 1 2 Whitford, David. "The Most Famous Story We Never Told". Fortune. Retrieved September 19, 2005.

- ↑ "Guide to the Records of Brown Brothers Harriman 1696 -1973, 1995 (bulk 1820-1968) MS 78". Dlib.nyu.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Press release, 1971 Museum of Modern Art

- ↑ Nau, Thomas (2007). Walker Evans: Photographer of America (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 59.

- ↑ Reena Jana. "Is It Art, or Memorex?". Wired.com. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Walker Evans". Masters of Photography. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "Walker Evans Entry St. Louis Walk of Fame: Walker Evans"

Sources

- "Furniture Store Sign, Birmingham, Alabama"

- Walker Evans exhibition in the argus fotokunst art gallery in Berlin.

Further reading

- Crump, James. Walker Evans: Decade by Decade. Hatje Cantz. ISBN 978-3-7757-2491-3.

- Hambourg, Maria Morris; Jeff Rosenheim; Douglas Eklund; Mia Fineman (2000). Walker Evans. Princeton University Press / The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-691-11965-1.

- Leicht, Michael (2006). Wie Katie Tingle sich weigerte, ordentlich zu posieren und Walker Evans darüber nicht grollte. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld. ISBN 3-89942-436-0.

- Mellow, James (1999). Walker Evans. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09077-8.

- Rathbone, Belinda (2002). Walker Evans: A Biography. Thomas Allen & Son Ltd. ISBN 0-618-05672-6.

- Rosenheim, Jeff; Douglas Eklund. Alexis Scwarzenbach, ed. Unclassified: A Walker Evans Anthology. Maria Morris Hambourg. Scalo / The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 3-908247-21-7.

- Storey, Isabelle (2007). Walker's Way: My Years With Walker Evans. PowerHouse Books. ISBN 978-1-57687-362-5.

- Worswick, Clark; Belinda Rathbone (2000). Walker Evans: The Lost Work. Arena Editions. ISBN 1-892041-29-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walker Evans. |

- Salt Lake Utah Article and photographs regarding Walker Evans' time spent in Ossining, NY.

- Biography of the artist Walker Evans from the J. Paul Getty Museum

- Walker Evans at the Art Institute of Chicago

- Luminous-Lint page

- Tod Papageorge on Walker Evans and Robert Frank

- "Many are Called" book review by Serhan Oksay