Walking Purchase

The Walking Purchase (or Walking Treaty) was a 1737 agreement between the Penn family, the proprietors of Pennsylvania, and the Lenape (also known as the Delaware). By it the Penn family and proprietors claimed an area of 1,200,000 acres (4,860 km²) and forced the Lenape to vacate it. The Lenape appeal to the Iroquois for aid on the issue was refused.

In Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania (2004), the Delaware nation (one of three federally recognized Lenape tribes) claimed 314 acres (1.27 km2) of land included in the original purchase, but the US District Court granted the Commonwealth's motion to dismiss. It ruled that the case was nonjusticiable, although it acknowledged that Indian title appeared to have been extinguished by fraud. This ruling held through the United States courts of appeals. The US Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

History

William Penn enjoyed a reputation for fair-dealing with the Lenape.[1] However, his heirs, John Penn and Thomas Penn, abandoned many of the elder Penn's practices. In 1736, they claimed a deed from 1686 by which the Lenape promised to sell a tract beginning at the junction of the Delaware River and Lehigh River (modern Easton, Pennsylvania) and extending as far west as a man could walk in a day and a half. This document may have been an unsigned, unratified treaty, or even an outright forgery (Encyclopædia Britannica refers to it as a "land swindle").[2] The Penns' agents began selling land in the Lehigh Valley to colonists while the Lenape still inhabited the area.

To allay the Lenapes’ misgivings, Penn Land Office Agent, James Logan, produced a map misrepresenting the farther Lehigh River as the relatively close Tohickon Creek, and including a dotted line showing a seemingly reasonable path that the “walkers” would take. Satisfied that the land in question was not so terrible a price to honor the old deed, the Lenape finally signed.[1]

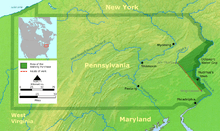

According to the popular account, Lenape leaders assumed that about 40 miles (60 km) was the longest distance that could be covered under these conditions. Provincial Secretary Logan, the legend continues, hired the three fastest runners in the colony, Edward Marshall, Solomon Jennings and James Yeates, to run on a prepared trail. They were supervised during the "walk" by the Sheriff of Bucks County, Timothy Smith. The walk occurred on September 19, 1737; only Marshall finished,[1] reaching the modern vicinity of present-day Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, 70 miles (113 km) away. At the end of the walk, Sheriff Smith drew a perpendicular line back toward the northeast, and claimed all the land east of these two lines ending at the Delaware River.

This resulted in an area of 20 acres (4,860 km²), roughly equivalent to the size of Rhode Island, located in the modern counties of: Pike, Monroe, Carbon, Schuylkill, Northampton, Lehigh and Bucks.

The Delaware leaders appealed for assistance to the Iroquois confederacy, who claimed hegemony over the Delaware. The Iroquois leaders decided that it was not in their best interest politically to intervene on behalf of the Delaware. James Logan had already made a deal with the Iroquois to support the colonial side. As a result, the Lenape had to vacate the Walking Purchase lands.

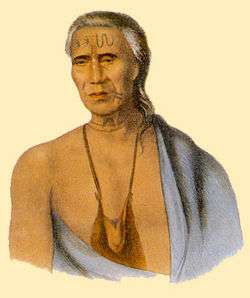

Chief Lappawinsoe and other Lenape leaders continued to protest the arrangement, as the Lenape were forced into the Shamokin and Wyoming valleys, already crowded with other displaced tribes. Some Lenape later moved west into the Ohio Country. Because of the Walking Purchase, the Lenape grew to distrust the Pennsylvania government, and its once good reputation with the various tribes was lost forever.

Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania

District Court (2004)

In 2004, the Delaware Nation filed suit against Pennsylvania in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, seeking 314 acres (1.27 km2) included in the 1737 Walking Purchase and patented in 1741, which was known as "Tatamy's Place." The court granted the Commonwealth's motion to dismiss.[3] According to the District Court:

- Penn's government and practices apparently differed sharply from the Puritan-led governments of the other American colonies. The most striking difference was Penn's ability to cultivate a positive relationship based on mutual respect with the Native Americans inhabiting the province. While the Puritans "stole from the Indians ... Penn achieved peaceful relations with the Indians."[3]

The District Court recounted its understanding of the facts of the Walking Purchase:

- Penn's sons were less interested than their father in cultivating a friendship with the Lenni Lenape. Thomas Penn, in particular, is reportedly responsible for executing The Walking Purchase of 1737, pursuant to which Thomas Penn approached the Lenni Lenape Chiefs and “falsely represented an old, incomplete, unsigned draft of a deed as a legal contract.” ( Compl. ¶ 38.) Thomas Penn represented to the Lenni Lenape Chiefs that some fifty years prior, the ancestors of the Lenni Lenape had signed documents stating that the “land to be deeded to the Penns was as much as could be covered in a day-and-a-half's walk.” ( Id.) Believing that their forefathers had made such an agreement, the Lenni Lenape Chiefs agreed to the terms of the deed and consented to the day-and-a-half walk.

- The Lenni Lenape Chiefs trusted that the “white men” would take a leisurely walk through the tangled Pennsylvanian forests along the Delaware. The Chiefs were not aware that they were about to lose a significant amount of land. Unbeknownst to the Lenni Lenape, Thomas Penn took measures to ensure that the distance covered by his “walkers” would be as large as possible. Among other things, Thomas Penn had a straight path cleared through the forests and hired three of the fastest runners in the province. “[H]e and his agents spent weeks mapping their route-which went northwest rather than north as the treaty specified-hacking trails out of the woods.” ( Id. ¶ 39.) In addition, Thomas Penn promised that the fastest runner would receive five pounds sterling and 500 acres of land. In the end, the runners of the Walking Purchase of 1737 procured 1,200 square miles [more than 1 million acres] of Lenni Lenape land in Pennsylvania. Included in the land procured was land commonly referred to as the “Forks of the Delaware,” which contained the parcel of land at the center of this dispute, “Tatamy's Place.”[3]

- The Lenni Lenape complained to the King of England about the execution of the “walk” by Penn and his agents to no avail. In response, the Lenni Lenape began their movement westward in compliance with their ancestors' purported agreement to the terms of the Walking Purchase's deed. Over a hundred years later, experts examining this deed concluded that the deed was a forgery. As a result of the Walking Purchase, members of the Lenni Lenape tribe, now recognized as The Delaware Nation, were segregated into pockets or parcels of land surrounded by non-tribal settlers. Such is what occurred with respect to a grant of land to Chief Tetamy and his band of Delawares.[3]

The Delaware conceded that Thomas Penn had "sovereign authority," but challenged the transaction on the ground that it was fraudulent.[3] The court held that the justness of the extinguishment of aboriginal title is nonjusticiable, including in the case of fraud.[3] Because the extinguishment occurred prior to the passage of the first Indian Nonintercourse Act in 1790, that Act did not avail the Delaware.[3]

Circuit Court (2006)

The Third Circuit affirmed.[4] The Circuit affirmed the holding that aboriginal title may validly be extinguished by fraud, and further held that the tribe had waived the issue of whether Penn was actually a sovereign purchaser below.[4] Moreover, the Circuit held that any grants to the tribe subsequent to the extinguishment could not re-establish aboriginal title.[4] Therefore, the Circuit did not consider the merits of the tribe's argument that:

- The Delaware Nation claims in its appeal that the King of England-not Thomas Penn-was the sovereign over the territory that included Tatamy's Place. Therefore, Thomas Penn could not extinguish aboriginal title via the Walking Purchase and, consequently, the Delaware Nation maintains a right of occupancy and use.[4]

Specifically, the Circuit found it insufficient that the complaint had alleged that Penn was "accountable directly to the King of England."[4]

The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Gilbert, Daniel. "What Ye Indians Call 'Ye Hurry Walk'", The Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Pennsylvania State University

- ↑ "Walking-Purchase" in Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania, 2004 WL 2755545 (E.D. Pa. 2004).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania, 446 F.3d 410 (3d Cir. 2006).

- ↑ Delaware Nation v. Pennsylvania, 549 U.S. 1071 (2006).

External links

- The Walking Purchase at the Lenape Tribe official site

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

- Pennsylvania State Archives