Warp-field experiments

Warp-field experiments are a series of current and proposed experiments to create and detect instances of spacetime warping. The ultimate goal is to prove or disprove the possibility of spacetime metric engineering with reasonable amounts of energy.

Motivation

Spacetime metric engineering is a requirement for physically recreating solutions of general relativity such as Einstein–Rosen bridges or the Alcubierre drive. Current experiments focus on the Alcubierre metric and its modifications. Alcubierre's work from 1994 implies that even if the required exotic matter with negative energy densities can be created, the total mass–energy demand for his proposed warp drive would exceed anything that could be realistically attained by human technology. Other researchers aimed to improve the energy efficiency (see Alcubierre drive: Difficulties), however the propositions remain mostly speculative. Research groups at NASA's Johnsons Space Center and Dakota State University currently aim to experimentally evaluate several new approaches, especially a redesigned energy-density topology as well as an implication of brane cosmology theory.[1][2] If space actually were to be embedded in higher dimensions, the energy requirements could be decreased dramatically and a comparatively small energy density could already lead to a spacetime curvature measurable using an interferometer.[3] The theoretical framework for the experiments dates back to work by Harold G. White from 2003 as well as work by White and Eric W. Davis from 2006 that was published in the AIP, where they also consider how baryonic matter could, at least mathematically, adopt characteristics of dark energy (see section below). In the process, they described how a toroidal positive energy density may result in a spherical negative-pressure region, possibly eliminating the need for actual exotic matter.[2][4]

Theoretical framework

The metric derived by Alcubierre was mathematically motivated by cosmological inflation. The original "warp-drive" spacetime metric can be written in (t,x,y,z) coordinates as:

It uses the curve (world line) where expresses the x-coordinate position of the moving spaceship frame.

The radius is the euclidean distance from the curve. Furthermore, is the speed of light and is equivalent to , the velocity associated with the curve.

The shaping function is any smooth function that satisfies and decreases from the origin, vanishing at for some point .

The driving phenomenon behind the apparently arbitrary velocity (including ) could be (and was) postulated to be the York extrinsic time, , defined as:

It provides for the contraction of space in front, and expansion in the back of the warp bubble. The idea can be seen in some way as an applied extension of the hypothesis that the early universe also saw a rapid inflationary expansion that possibly exceeded the speed of light for some time. However, according to research,[2] it appears that the York time behaviour is merely a side effect of another underlying mechanism. The problem that led to the assumption that York time is only one part in the larger picture is the unusual symmetry in the required energy density. Using the Einstein field equations, the stress energy tensor can be derived from the Alcubierre metric, resulting in the necessary energy density:

where is the gravitational constant and .

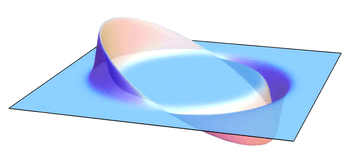

This corresponds to a negative toroidal energy density symmetric to the x-axis. It is notable here, that during a sensitivity analysis for the DARPA-funded 100 Year Starship symposium, Harold White discovered that changing the energy-density distribution from a thin ring as originally proposed to more of a doughnut shape (effectively increasing the warp-bubble wall thickness) can decrease the required total negative energy by several orders of magnitude.

The symmetry in the energy distribution leads to the scenario in which the choice of positive x-axis is in fact arbitrary. The warp-drive mechanism would not know whether to go forward or backward along the x-axis. This paradox can be resolved by putting the Alcubierre metric into canonical form using Rindler's method and extracting the potential, . With the potential it is possible to derive the field equation for the spacetime expansion "boost", :[4][5]

The boost can roughly be seen as a scalar multiplier acting on an initial velocity leading to the actual warp-velocity:

This boost is also an important analogy when considering higher-dimensional models (as seen below). The expansion and contraction of space as measured by York time are now more of a secondary effect and can be considered equivalent to a pressure gradient of a moving sphere in a fluid. The scalar nature of the effect is an important clue when considering higher dimensions. Considering the null geodesics for inside the warp field, it can be seen that the world lines are space-like for external observers, but the moving frame never travels outside its local comoving light cone and thus does not violate special relativity.[2]

From there on, White and Davis showed similarities of the spacetime boost when considered in a higher-dimensional spacetime, such as in the Chung-Freese model. In this particular model our space exists on a brane and the space surrounding the brane is called the "bulk". The size of each extra dimension is considered to be at least finite and the latest research at CERN also constrains any large extra dimension theories.[6] However, the actual size and total number of extra dimensions is not important when considering the implications on the boost field. The modified Robertson–Walker metric representing the model by Chung and Freese is:[7]

where the term specifies our normal space and the higher-dimensional bulk with our space located at the plane.

is a typical cosmological expansion parameter (see accelerated expansion) and is an arbitrary compactification factor for the extra dimensions. Considering the null geodesic solutions ( ds²=0 ) allows to develop the following relationship:

For zero the expected speed of the photon is c, as expected. For large off-bulk coordinates the speed can be made arbitrarily large.

That means that light rays could have a spacelike appearance, an obvious parallel to the Alcubierre model. However, in the Alcubierre model the spacetime expansion boost is the driving phenomenon, whereas in the Chung–Freese model the off-brane bulk location U serves this purpose. It is thus theoretically possible that the boost of a 3+1 spacetime model is a scalar correction factor for higher-dimensional geometric effects on our brane, leading the following analogies to Alcubierre's model:

- and thus

If a particle like an electron gains a high spacetime boost relative to an observer, it might actually leave the 3+1 brane (i.e. it gains non-zero U bulk coordinates) and its ability to interact electromagnetically diminishes. To illustrate this, White and Davis stated that in a 2D lab located at the x,y plane, a 2D electron that gets accelerated (obtains a high boost) gains a non-zero z coordinate. Thus, if a photon were to interact with it, it would need to be at the same (t,x,y,z) coordinate.

Considering the null geodesic equation again, one can see that if dU/dt=c, dX/dt=0 meaning that light comes to a standstill. This implies that a high hyperspace velocity reduces spacetime's "stiffness" or ability to resist being curved by energy, effectively reducing the energy requirements to warp it. This observation, together with the modified energy density distribution, first led researchers at NASA to begin thinking of testbeds to verify the new theoretical approach. Using the analogy between U and , it is obvious that a high velocity (dU/dt) with U=0 requires a field oscillation.

Back in the Alcubierre model, it is notable that an outside observer would perceive a uniform potential (from the uniform boost within the sphere) that represents the warp-field region even though it originates from a toroidal energy density. It has similar characteristics as a Gaussian spherical surface held at constant electrostatic potential. To the outside observer, the warp-field sphere has a uniform energy density. By expanding the spherical region while maintaining the same relative boost value for the Gaussian surface, when considering the first law of thermodynamics, the following can be concluded (limited to the 3+1 brane):

can be replaced by , which is the total energy for the warp sphere with the same volume change as on the right side of the equation.

Thus, the equation of state relating the pressure of the warp sphere to its energy density is

which noticeably resembles the equation of state of cosmological vacuum energy (moreover, it is the equation of state of dark energy). If of the original warp sphere is negative, would be positive. However the last equation shows that the opposite is true, is positive and is negative. Considering that the spacetime expansion boost for the Alcubierre model can be made arbitrarily high depending on the choice of input variables, a high boost is thereby clearly not an exclusive feature common only to negative energy densities and could be obtained in the lab, provided powerful enough equipment.[2]

Difficulties

Einstein's field equations show that comparatively high amounts of energy are required for any significant curvature of spacetime under ordinary conditions. With the energy-requirement-decreasing concepts only being partially implemented yet, the available measurement methods are reaching the limits of what is technically possible. That is why current results remain mostly inconclusive until measurements can be further refined or the effect can be increased. New experimental setups have been proposed to boost sensitivity, and using the higher-dimensional yet still purely theoretical approach may increase any effect sufficiently to obtain significant results to prove or disprove the theory.

Current experiments

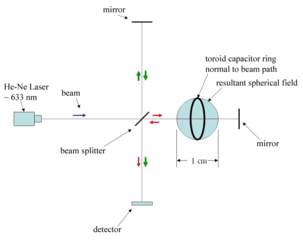

The only reported warp-field experiment currently being conducted is on a modified Michelson–Morley interferometer as proposed by Harold White and Eric Davis in 2003. This setup includes a ring-shaped energy device using high-voltage barium-titanate ceramic capacitors to attempt to warp space as shown in the diagram. White announced at a 2013 space conference that the first experimental results from this device were inconclusive.[1]

Proposed experiment

A time-of-flight experiment was proposed in 2013 using a modified Fabry–Pérot interferometer.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Dr. Harold “Sonny” White (2013-08-17). "2013 Starship Congress: Warp Field Physics, an Update". Icarus Interstellar. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White, H.; Davis, E. (2006). M. S. El-Genk, ed. "The Alcubierre Warp Drive in Higher Dimensional Space-time" (PDF). Proceedings of Space Technology and Applications International Forum. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ White, Harold (January 2013). "Warp Field Mechanics 102: Energy Optimization". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- 1 2 Harold “Sonny” White (2011-09-30). "Warp Field Mechanics 101" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ White, H., “A Discussion on space-time metric engineering,” Gen. Rel. Grav. 35, 2025-2033 (2003).

- ↑ Collaboration, CMS; Sirunyan, A.M.; Tumasyan, A.; Adam, W.; Bergauer, T.; Dragicevic, M.; Erö, J.; Fabjan, C.; Friedl, M.; Frühwirth, R.; Ghete, V.M.; Hammer, J.; Hänsel, S.; Hartl, C.; Hoch, M.; Hörmann, N.; Hrubec, J.; Jeitler, M.; Kasieczka, G.; Kiesenhofer, W.; Krammer, M.; Liko, D.; Mikulec, I.; Pernicka, M.; Rohringer, H.; Schöfbeck, R.; Strauss, J.; Taurok, A.; Teischinger, F.; et al. (2010). "Search for Microscopic Black Hole Signatures at the Large Hadron Collider". Physics Letters B. 697 (5): 434. arXiv:1012.3375

. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2011.02.032.

. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2011.02.032. - ↑ "Chung-Freese-Model" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-10-08.