Waterloo Village, New Jersey

- Not to be confused with Waterloo, Monmouth County, New Jersey.

|

Waterloo Village | |

|

Smith's General Store at Waterloo Village, with the Morris Canal in the immediate background | |

| |

| Nearest city | Byram, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°54′56″N 74°45′22″W / 40.91556°N 74.75611°WCoordinates: 40°54′56″N 74°45′22″W / 40.91556°N 74.75611°W |

| Area | 70 acres (28 ha) |

| Built | 1820 |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP Reference # |

77000909[1] (original) 15000176 (increase) |

| NJRHP # | 2593[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 13, 1977 |

| Boundary increase | April 28, 2015 |

| Designated NJRHP | February 3, 1977 |

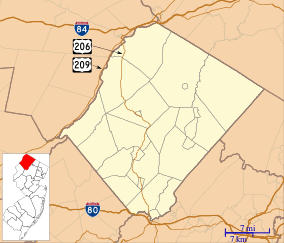

Waterloo Village is a restored 19th-century canal town in Byram Township, Sussex County (west of Stanhope) in northwestern New Jersey, United States. The community was approximately the half-way point in the roughly 102-mile (165 km) trip along the Morris Canal, which ran from Jersey City (across the Hudson River from Manhattan, New York) to Phillipsburg, New Jersey, (across the Delaware River from Easton, Pennsylvania). Waterloo possessed all the accommodations necessary to service the needs of a canal operation, including an inn, a general store, a church, a blacksmith shop (to service the mules on the canal), and a watermill. For canal workers, Waterloo's geographic location would have been conducive to being an overnight stopover point on the two-day trip between Phillipsburg and Jersey City.

It is currently an open-air museum in Allamuchy Mountain State Park. As part of the State Park, it is open to the public from sunrise to sunset. The village is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Canal and railroad eras

Although opened in 1831, the Morris Canal's traffic volume, which was primarily anthracite coal from Pennsylvania, peaked during the late 1860s, shortly after end of the American Civil War. Up until that time, the local railroads — the Lackawanna Railroad's Sussex Branch and Morris and Essex Railroad — had only supplemented the canal's operation, rather than actually competing with it. Both the Sussex Branch and the Morris & Essex Railroad ran within a short distance of the village. After the War, however, the canal's traffic began to quickly shift over to the much faster and more reliable railroad. It was expected that during most winters the canal would be frozen solid, and thus impassable during the time when its chief commodity was in greatest demand.

As a result, the canal underwent a steady decline, and so did Waterloo Village. Although the canal was not officially abandoned until 1924, rarely did more than one boat a year (to fulfill the conditions of the canal's charter) run through the canal after 1900. By the time of the Great Depression, Waterloo Village had been abandoned by its original owners.

Unheralded saviors

This might have been the end of the story for Waterloo, particularly if the hamlet had really been abandoned, as local vandals might have burned the town to the ground if it had become completely unoccupied. But the village's location, within a short distance of the Lackawanna Railroad (which had to overcome a steep eastbound grade towards New York near Waterloo, slowing freight trains to a crawl as they labored up the hill to Netcong), made it easy for hobos to jump on and off boxcars.

The hobos, as it turned out, had "discovered" Waterloo and had adopted it as a stopping off point in their cross-country journey towards New York. This new purpose for the village wasn't all that different from its original purpose a century earlier. The hobos protected Waterloo Village by occupying it throughout the 1930s and '40s. The original Waterloo railroad station was moved from the station site during the 1940s and became a private residence on U.S. Route 206 in Mount Olive Township, New Jersey.[3]

Rebirth

If one person deserves credit for saving Waterloo Village in the modern era, it's Percival H.E. Leach. Percy Leach, as he is known, with his partner Lou Gualandi, spearheaded an effort to preserve the village, starting during the 1960s. Over time, and with volunteer help, the village was slowly restored. (The village would eventually become part of New Jersey's Allamuchy Mountain State Park.)

The Waterloo Foundation for the Arts, a not-for-profit corporation, was established and enabled Leach and Gualandi to raise the funds necessary to not only restore the village, but also to expand its operation to include classical and pop concerts that brought in additional revenue.

By the mid-1980s, Waterloo had become a regular stop for performing artists and was envisioned as the New Jersey equivalent of Tanglewood, with a proposal that an amphitheater would open and would become the summer home of New York's Metropolitan Opera.

Controversy, downfall, and closure

With the death of Lou Gualandi in 1988, however, Percy Leach lost his most trusted advisor, and the one who had been the voice of moderation in their relationship. Following Gualandi's death, Leach became involved in several controversial projects that brought greater scrutiny upon the Waterloo Foundation for the Arts. The most controversial was the so-called "land swap" that allowed BASF corporation to build a large corporate headquarters on land that had once been part of Allamuchy Mountain State Park. The swap, which was expedited by then New Jersey Governor Thomas Kean, a Leach family friend who had worked as a volunteer at Waterloo during the nascent stages of the village's rebirth in the 1960s, was to pave the way for the aforementioned amphitheater complex, a project that never got past the initial planning stages.

The BASF issue, which had aroused considerable opposition, ushered in a period of uncertainty for Waterloo Village and to some degree contributed to Leach's eventual ouster from his key position with the foundation. The Waterloo board of directors subsequently brought in a new management team and throughout the mid- to late-1990s tried to rebuild trust in the running of the village. Over this time, the foundation slowly downsized the concerts that were held in association with the village, as some of the earlier rock concerts had drawn nearly 20,000 spectators and had completely overwhelmed the area's limited access roads and had caused considerable friction with the surrounding towns.

In the period from 2003 to 2006, the Waterloo Foundation for the Arts had received $900,000 from the State of New Jersey for general expenses, along with more than $300,000 since 2000 to cover repairs. As the state showed increasing displeasure with the village's operation, the $250,000 the group had expected to receive, which would have been used towards the $2 million operating budget for the site, was cut from the 2007 state budget. Waterloo Village was shut down in December 2006, except for the privately owned Waterloo United Methodist Church, which has a small but dedicated congregation and continues to operate as it has for over 150 years while the fate of the village itself is uncertain. Since 2006, the Village has been open intermittently. For example, in late September, 2008, the concert stage was temporarily opened for the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival.

2014 season

Through a concession agreement with the NJDEP Division of Parks and Forestry, group tours and programs are available at Waterloo Village, Allamuchy Mountain State Park, by reservation with Winakung at Waterloo Inc. Programs at the recreated Lenape Indian Village and/or historic Village of Waterloo are offered April through November. Winakung at Waterloo Inc. educational programs meet core curriculum standards and are ideal for school trips, scout groups, and summer camp field trips. Winakung at Waterloo Inc. also offers year round outreach programs for schools, libraries, historical societies, Clean Communities and more. http://winakungatwaterloo.com/

In the spring of 2014, a 10-year lease (with the option of 10 more) was awarded to Jeffrey Miller Catering (JAM Catering) out of Philadelphia, making them the exclusive caterer for Waterloo Village. JAM has renovated the Meeting House and Pavilion, and is currently creating a "Bride's Cottage" on the property, making it a beautifully rustic site for Weddings and Events. http://jamcater.com/

May 2014 saw the launch of the SMS Italian Festival. This annual Non-Profit event supports the children of St Michael School. 100% of the proceeds will be used to provide a safe and healthy environment for learning. Placing a focus on developing and encouraging the full potential of children, creates a family oriented event that becomes a favorite for the surrounding communities as the "key event" to kick-off summer fun. The Festival includes Children & Adult Rides, Games, International Food, Vendors, Beer & Wine Garden, Daily Entertainment/Events and a Signature Fireworks Display. 2015 SMS Italian Festival Dates - May 28–31. Click Here to learn more

Movie set

Much of the principal photography for writer/director Michael Pleckaitis' silent film Silent was done in November and December 2006 at various locations in the village.[4]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sussex County, New Jersey

- List of museums in New Jersey

Gallery

- A small aqueduct crosses the old canal lock at Waterloo Village

- Mule pulls canal boat along a remaining watered section of the Morris Canal on Canal Day at Waterloo Village in 1998.

Tents for Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation Poetry Festival 2008.

Tents for Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation Poetry Festival 2008.- Production photo from 2007 film Silent. Smith's General Store and Morris canal in background.

- The Meeting House, the one major modern addition, used for wedding receptions and other functions.

- A modern-day view of the Waterloo station site, looking westbound.

Notes and references

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places - Sussex County" (PDF). NJ DEP - Historic Preservation Office. April 1, 2010. p. 12. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ↑ Waterloo Village is about 3/10 mile (0.5 km) off to the right, although Interstate 80 has since been built in between. The Sussex Branch Railroad once originated here and almost immediately passed over the inclined plane of the canal located near Waterloo on the trip to Branchville. Due to the branch's obsolete westerly alignment (facing away from the photographer, for coal shipments from Pennsylvania) the branch's connection with the main line was moved to Netcong in 1903 to better serve passengers going towards New York, but further isolating the bucolic hamlet of Waterloo.

- ↑ Kwoh, Leslie. "Silver screen redux: Film gets silent treatment", The Star-Ledger, July 8, 2007. Accessed July 13, 2007. "For the past nine months, Pleckaitis and his band of 60 volunteer actors, most of them from New Jersey, have worked to capture two hours worth of classic film at historic spots like the Deserted Village in Watchung, Waterloo Village in Stanhope and the Presbyterian Cemetery in Madison."

External links

- Winakung at Waterloo Inc. Fully Guided and Interpreted Educational Tours of Waterloo Village and Winakung, the recreated Lenape Native American Village

- Canal Society of New Jersey

- NJ Dept. of Parks & Forests - Information on 2008 events at Waterloo Village

- Allamuchy Mountain State Park

- Allamuchy parks