Wey and Godalming Navigations

| River Wey and Godalming Navigations | |

|---|---|

|

Catteshall Lock, the southernmost lock on the Navigations at Farncombe, Godalming, Surrey. | |

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 16 |

| Status | open |

| Navigation authority | National Trust |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1651 |

| Date of first use | 1653 |

| Date extended | 1764 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | River Thames |

| End point |

Godalming (originally Guildford) |

| Connects to |

Basingstoke Canal Wey and Arun Junction Canal |

Wey and Godalming Navigation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The River Wey Navigation and Godalming Navigation, geographically (but not historically) the Wey Navigation, form a continuous waterway which provides a 20-mile (32 km) navigable route from the River Thames between Weybridge and Hamm Court, Addlestone via Guildford to Godalming. The waterway is in Surrey and is owned by the National Trust. The Wey Navigation connects to the Basingstoke Canal at West Byfleet, and the Godalming Navigation part to the Wey and Arun Canal in the Broadford part of Shalford. The Navigations consist of man-made canal and adapted (dredged and straightened) parts of the River Wey. Its adjoining path is part of European long-distance path E2.

The Wey was the second river in England to be turned from wholly unnavigable to navigable for its main town, as it was behind the River Lea; the River Wey Navigation opened in 1653 with 12 locks between Weybridge and Guildford. Construction of the Godalming Navigation, a further four locks, was completed in 1764 connecting a second market town. Commercial traffic (save for exceptional loads for canalside buildings) ceased in 1983 and the Wey Navigation and the Godalming Navigations were donated to the National Trust in 1964 and 1968 respectively.

History

The River Wey has two main sources, which form the North Branch and the South Branch, and which join together at Tilford. The combined flow continues to Godalming, cuts through the chalk of the North Downs at Guildford, and passes through the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty to join the River Thames at Weybridge.[1][2] It had been used by small boats since medieval times,[3] and some improvements were made to the channel from 1618.[2]

Sir Richard Weston was an owner of land beside the river, and had been responsible for a 3-mile (4.8 km) cut through his land in 1618-1619, running from Stoke Mills to Sutton Green. It included a towing path and several bridges, together with a number of sluices which enabled him to flood 150 acres (61 ha) of his land in a controlled manner, thus creating water-meadows. As a catholic and a royalist, his property was sequestrated during the English Civil War and he fled to the Low Countries, where he studied inland navigations and the working of pound locks. He returned to England in the late 1640s, and proposed a scheme for making the Wey navigable to Guildford by the use of such locks. Guildford Corporation had petitioned Parliament in 1621 and 1624 for a scheme using flash locks, but there is no evidence that the proposals had been properly surveyed or costed, and nothing came of them. In order to progress the scheme, Weston needed his sequestration to be discharged, and someone to take an interest in the Wey. He found an ally in James Pitson, who had been a Major in Cromwell's army, and who was now Commissioner for Surrey. He was able to get Weston acquitted, and presented a bill to Parliament in December 1650, which became an Act of Parliament on 26 June 1651.[4]

The Act allowed the undertakers to raise £6,000 by issuing 24 shares, and the shares were bought by Weston, who took 12, and by Pitson, Richard Scotcher, and another man, who took four each.[4] The Act also specified a maximum toll for carriage of goods over the length of the navigation. This was set at four shillings (20p), which was less per mile than the rate for goods on the River Avon at Bristol, which had been set 60 years earlier. A charge for passengers was also specified, and a charge for freight, if the undertakers chose to run their own barges.[5] Work began in August 1651, with Weston acting as engineer, and a work force of some 200 men were employed. Weston died on 17 May 1652, but by that time, he had already completed 10 miles (16 km) of the 15-mile (24 km) route. In addition to his initial shareholding, he had contributed a further £1,000 and supplied timber from his estate valued at £2,000. Weston's role was taken on by his son, George. Scotcher managed the accounts and the workforce, while Pitson found others who were willing to contribute to the cost of the scheme.[4]

The work was completed in November 1653, at a cost of £15,000. There were around 9 miles (14 km) of new cuts, four new weirs, twelve bridges, and a wharf at Guildford. The level dropped by 72 feet (22 m) between Guildford and Weybridge. Skempton says that 10 new locks dropped the level by 60 feet (18 m), while Hadfield says that the new work included 12 locks. Hadfield's total presumably includes the two flood gates at Walsham and Worsfold, which protect long cuts. All of the new locks were turf sided with timber framework. Although the navigation was a success, with tolls soon raising £1,500 per year, disputes and litigation over financial matters occurred for some years, involving Weston's older son and heir John, Scotcher, Pitson, and a number of other contributors. A second Act of Parliament was obtained in 1671, in an attempt to resolve matters, which placed the river under the control of six trustees, with a board to pronounce on disputes. It took another six years to work out, by which time maintenance arrears caused by neglect and wilful damage required several thousand pounds to be spent to put things right.[4][5]

A further bill was presented to Parliament in 1759, to authorise an extension of the navigation for a further 4.5 miles (7.2 km) up to Godalming. It was not successful, but an Act of Parliament was obtained in the following year. John Smeaton and then Richard Steadman acted as engineers. The work involved the construction of another four locks, and the project cost £6,450. The Godalming Navigation opened for trade in 1763, and was managed by Commissioners, who formed a separate legal entity to those responsible for the navigation below Guildford.[6]

Operation

The navigations were used for transporting barge loads of heavy goods to London. Timber, corn, flour, wood and gunpowder from the Chilworth mills moved north along the canal and then down the Thames to London while coal was brought back principally for gunpowder making and smithery. Other cargoes included sugar and bark, which was used for tanning.[7] The trade in timber had been established well before the river was canalised, and in 1664, 4,000 loads of timber were reported to have passed down the river. Daniel Defoe, in A tour through England and Wales, noted very great quantities of timber using the river, which was brought to Guildford from forests in Sussex and Hampshire up to 30 miles (48 km) away during the summer months. The Rev. W Gilpin, writing in 1776, recorded that timber was floated down the river, with each load steered by a man with a pole. There was a significant trade in hoops and paper, while Defore recorded that corn was bought at the corn market in Farnham, to be transported to the mills on the river by boat, and then shipped to London once it had been processed.[6]

Trade developed during the American war of independence between 1780 and 1783, when war stores were moved from London to Godalming, to be transported overland to Portsmouth. Additional tolls were raised from traffic using the first 3 miles (4.8 km) of the navigation to reach the Basingstoke Canal after that opened in 1794. Fear of the French during the Napoleonic Wars meant that trade between London and the south and west was not sent by sea, and again the navigation benefitted.[8] The Wey and Arun Canal linked the Godalming Navigation to the River Arun in Sussex in 1816, forming part of a grand scheme to link London to Portsmouth. Its opening coincided with the end of the war with France, after which coastal trade resumed, and the new canal never met the expectations of its promoters.[9] It had been expected that the new canal would result in a fall in the price of coal at Guildford, as supplies came up the Arun from the South Wales coalfields, but improvements to the Thames and reductions in coal prices resulted in Guildford being still supplied with coal from London, and coal traffic continuing south along the Wey and Arun as far as Loxwood.[10]

Average profits which were £2,046 for the years 1794 to 1798, rose to £4,079 for the years 1809 to 1813. 24,006 tons of goods were carried in 1780, and this had increased to 55,035 tons by 1830. In 1831, 827 loaded boats made the journey upstream, carrying 31,544 tons. Of this, coal accounted for 12,859 tons, corn for 6,155 tons and groceries for 5,719 tons. In the downward direction, 867 loaded boats carried 25,645 tons. 9,632 tons of this were timber, in various forms. Most of the trade in hoops for barrel making and bark for tanning came from the Wey and Arun Canal, and accounted for 4,761 and 2,798 tons respectively. Processed flour, ground by the mills along the river, contributed 5,593 tons, with much of the rest being manufactured goods. This included 589 tons of spokes and other parts for the manufacture of carts, originating on the Wey and Arun Canal; 482 tons of ale and 87 tons of pottery, nearly all of which originated on the Basingstoke Canal; and 79 tons of gunpowder, produced by the gunpowder mills at Shalford.[10]

Management

After 1677, the shares in the Wey Navigation were split into two moieties, owned initially by Dickenson and by Tindall and Cressey jointly. George Langton obtained all of the shares in one moiety by 1699, as both Tindall and Cressey had died, and managed the navigation until 1715. Winifred Hodges, who was Dickinson's heir, then managed to obtain joint control, and her shares were sold to Lord Portmore in 1723. The Portmores and Langtons continued to manage the navigation into the nineteenth century, but the death of one shareholder had often resulted in those shares being distributed among several heirs. This happened again in 1801 when Bennet Langton died, and in 1835 when the third Lord Portmore died. The Portmore moiety was obtained by William Stevens II in 1888, and most of the Langton moiety by William Stevens III, his son, in 1911.[11]

The Stevens family were connected with the navigation from 1812, when the first William Stevens was employed as the lock-keeper at Trigg Lock. He moved on to Thames Lock in 1820, and then became the wharfinger at Guildford in 1823. He also built up a business as a coal merchant, and was succeeded by his son William Stevens II in 1856. William II became general manager of the Godalming Navigation in 1869, and obtained the Portmore shares in 1888. On his death two years later, William Stevens III became the manager of both navigations, but sought to ensure ownership by buying up most of the Langton shares.[11]

The coming of the railways from the 1840s marked the start of decline for many canals. The Way and Arun Canal was no exception, and most of its trade had gone by the 1850s. It closed in 1871, and although this had little effect on the Wey Navigation, its effect on the Godalming Navigation was much more severe, as there was little business to sustain it, unlike on the Wey, where the corn mills continued to send their goods by boat. Tonnage fell from a peak of 86,003 tons in 1838 through 70,000 tons in 1845 to 24,581 tons in 1890, but the Stevens family fought hard to maintain the navigation, and traffic rose again to over 30,000 tons from 1890 to 1910, with a rise to 51,115 tons in 1918.[11] In 1912 Stevens went to court to transfer the powers of the Trustees to his family. As well as managing the navigations, the Stevens were also carriers, and their fleet helped to maintain trade at a healthy level between 1918 and 1939. The connection via the Thames to the London Docks and the number of corn mills on the river were also factors, as was a steady increase in leisure traffic,[12] which had generated income of £371 as early as 1893.[13]

Decline and restoration

Harry Stevens took over the running of the navigations in 1930, at a time when industries were beginning to close, or transfer traffic to the roads, and when a major restructuring of the Wey valley was just starting, to improve flood relief. This involved building new weirs and relief channels, including the Broad Mead Cut, which ran between Cartbridge and Papercourt. By the 1940s the Godalming Navigation was virtually derelict, and trade declined when Newark Mill closed during the Second World War. When traffic from Coxes Mill ceased in the 1960s, the navigation was no longer viable, and Stevens gave it to the National Trust in 1964. Ownership passed to them in 1971, when Stevens' wife died. The Commissioners of the Godalming Navigation gave their rights to Guildford Corporation in 1968, who passed it on to the National Trust, and for the first time, both parts of the river were under common ownership. The last commercial barge ran in 1969, although there was some commercial traffic in the early 1980s from Tilbury to Coxes Mill.[12]

The National Trust had some experience at managing waterways, having been responsible for the Stratford Canal since 1960.[14] Early restoration work was carried out by volunteer working parties, which were publicised in Navvies Notebook, produced by the London and Home Counties Branch of the Inland Waterways Association to co-ordinate voluntary activity on the canals.[15] The Trust have established a visitor centre at Dapdune Wharf, where eleven barges were built for the navigation. Two of them are on display. Reliance was built in 1931-1932, and was for many years abandoned on mud flats at Leigh-on-Sea after sinking when it hit Cannon Street Railway Bridge in London in 1968. It was salvaged from the mud flats in 1996 and has been restored. Perseverence IV was built in 1935, and was in commercial traffic until 1982; it was restored in 1998.[16][17]

Features along the canal

This summary is in upstream order from the River Thames. Between the Town Lock (or Weybridge Lock) and Coxes lock is the Blackboys footbridge by Blackboy Farm and, after a railway bridge, Coxes Mill in three Grade II listed blocks.[18] With its little island and accompanying weir which helps to drain the 5-acre (2-hectare) mill pond, Coxes lock is the deepest unmanned lock on the Navigation with a rise of 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m). Between New Haw Lock and Pyrford Lock is one end of the Basingstoke Canal just before the Woodham footbridge, Byfleet boat club, built in the 1900s, Grist Mill, Parvis Wharf, Murray's footbridge and Dodds footbridge.

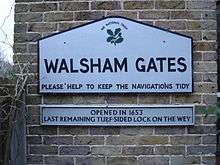

Between Pyrford Lock and Newark Lock are the Walsham Gates and the battered walls of Newark Priory on its own long short-grass island. Between Papercourt Lock and Triggs Lock are the Tanyard footbridge, High Bridge (foot), Cartbridge Wharf, Cart Bridge and Worsford Gates. Between Triggs Lock and Bowers Lock are the Send Church footbridge and Broad Oak Bridge. Between Stoke Lock and Millmead Lock are Stoke Mill, Dapdune Wharf and Guildford Town Wharf. Finally between Millmead Lock and Unstead Lock are the Guildford boathouse, a footbridge carrying the North Downs Way and Broadford Bridge.

Towpath and footpath links

The towpath is a free access national trail, a local authority-supported, car-free, main north-south route. Linking with the Basingstoke Canal towpath at Byfleet, it has links with many public footpaths and with two National Trails. These are the Thames Path at Weybridge and the North Downs Way at St. Catherines, Guildford. This section of the towpath has been made part of European long-distance path E2. This runs from Galway in Ireland to Nice on the Mediterranean coast of France.

Downs Link

The railway line between Guildford and Horsham, the Cranleigh Line, crossed the Wey just south of the entrance to the Wey and Arun Canal. The line for building materials, agricultural goods, wood and coal was in direct competition with that canal and accelerated its demise. However, the railway closed in 1965, as a result of the Beeching Axe, and the bridge across the combined river and canal was soon after demolished, leaving just the supporting abutments.

With the 21st opening of the Downs Link national trail a footbridge has been constructed at the same location using the existing abutments to link the trails which run along the former trackbed. Opened on 7 July 2006, the Unstead Woods Downslink Bridge, a single-span metal structure provided a cycle and pedestrian connection across the river.[19]

Gallery

Part of the house where John Donne lived, Pyrford

Part of the house where John Donne lived, Pyrford Lock sign at Pyrford completed in 1653, the end of the longest section

Lock sign at Pyrford completed in 1653, the end of the longest section Canal and River Wey at Walsham Gates

Canal and River Wey at Walsham Gates Canal north of Catteshall Lock near a weir, Springtime 2007

Canal north of Catteshall Lock near a weir, Springtime 2007

Further reading

- Inland Waterways Association (South-East Region) The River Wey and Godalming Navigation: Weybridge to Godalming Inland Waterways Association 1976

See also

Bibliography

- Currie, Christopher K (September 1996). "A Historical and Archaeological Assessment of the Wey and Godalming Navigations and their Visual Envelopes". The National Trust.

- Fisher, Stuart (2013). British River Navigations. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-0084-5.

- Hadfield, Charles (1969). The Canals of South and South-East England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4693-8.

- Nicholson (2003). Nicholson Guides Vol 2: Severn, Avon & Birmingham. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-721110-4.

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 7: River Thames and the Southern Waterways. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-721115-9.

- Skempton, Sir Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2939-2.

- Squires, Roger (2008). Britain's restored canals. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84306-331-5.

References

- ↑ Ordnance Survey, 1,25,000 map

- 1 2 Fisher 2013, p. 236.

- ↑ Nicholson 2006, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 4 Skempton 2002, p. 770.

- 1 2 Hadfield 1969, p. 118.

- 1 2 Hadfield 1969, p. 119.

- ↑ Cumberlidge 2009, p. 330.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, pp. 133-134.

- 1 2 Hadfield 1969, pp. 120,123.

- 1 2 3 Currie 1996, p. 3.7.

- 1 2 Currie 1996, p. 3.8.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, p. 124.

- ↑ Nicholson 2003, p. 137.

- ↑ Squires 2008, pp. 62, 66.

- ↑ Nicholson 2006, p. 184.

- ↑ Fisher 2013, p. 239.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1029190)". National Heritage List for England.

- ↑ The River Wey and Navigations: Details of bridge

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wey Navigation. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Godalming Navigation. |

- National Trust – Dapdune Wharf and River Wey Navigations

- Environment Agency – River Wey Catchment Flood Warnings

- Guildford Rowing Club

- Wey Kayak Club

- The River Wey and Wey Navigations Community Site

| Next confluence upstream | River Thames | Next confluence downstream |

| River Bourne, Addlestone River Bourne, Chertsey (south) |

Wey and Godalming Navigations | River Wey (south) |

Coordinates: 51°19′54.69″N 0°29′15.8″W / 51.3318583°N 0.487722°W