Whisky

Whisky or whiskey[1] is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn (maize), rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden casks, generally made of charred white oak.

Whisky is a strictly regulated spirit worldwide with many classes and types. The typical unifying characteristics of the different classes and types are the fermentation of grains, distillation, and aging in wooden barrels.

Etymology

The word whisky (or whiskey) is an anglicisation of the Classical Gaelic word uisce (or uisge) meaning "water" (now written as uisce in Irish Gaelic, and uisge in Scottish Gaelic). Distilled alcohol was known in Latin as aqua vitae ("water of life"). This was translated to Classical Gaelic as Irish: uisce beatha/Scottish Gaelic: uisge beatha "water of life". Early forms of the word in English included uskebeaghe (1581), usquebaugh (1610), usquebath (1621), and usquebae (1715).[2]

Names and spellings

Much is made of the word's two spellings: whisky and whiskey.[3][4] There are two schools of thought on the issue. One is that the spelling difference is simply a matter of regional language convention for the spelling of a word, indicating that the spelling varies depending on the intended audience or the background or personal preferences of the writer (like the difference between color and colour; or recognize and recognise),[3][4] and the other is that the spelling should depend on the style or origin of the spirit being described. There is general agreement that when quoting the proper name printed on a label, the spelling on the label should not be altered.[3][4] Some writers refer to "whisk(e)y" or "whisky/whiskey" to acknowledge the variation.

The spelling whiskey is common in Ireland and the United States, while whisky is used in all other whisky producing countries.[5] In the US, the usage has not always been consistent. From the late eighteenth century to the mid twentieth century, American writers used both spellings interchangeably until the introduction of newspaper style guides.[6] Since the 1960s, American writers have increasingly used whiskey as the accepted spelling for aged grain spirits made in the US and whisky for aged grain spirits made outside the US.[7] However, some prominent American brands, such as George Dickel, Maker's Mark, and Old Forester (all made by different companies), use the whisky spelling on their labels, and the Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits, the legal regulations for spirit in the US, also use the whisky spelling throughout.[8]

"Scotch" is the internationally recognized term for "Scotch whisky".

History

It is possible that distillation was practised by the Babylonians in Mesopotamia in the 2nd millennium BC, with perfumes and aromatics being distilled,[9] but this is subject to uncertain and disputed interpretation of evidence.[10] The earliest certain chemical distillations were by Greeks in Alexandria in the 1st century AD,[11] but these were not distillations of alcohol. The medieval Arabs adopted the distillation technique of the Alexandrian Greeks, and written records in Arabic begin in the 9th century, but again these were not distillations of alcohol.[10] Distilling technology passed from the medieval Arabs to the medieval Latins, with the earliest records in Latin in the early 12th century.[10][12] The earliest records of the distillation of alcohol are in Italy in the 13th century, where alcohol was distilled from wine.[10] An early description of the technique was given by Ramon Llull (1232 – 1315).[10] Its use spread through medieval monasteries,[13] largely for medicinal purposes, such as the treatment of colic and smallpox.[14]

The art of distillation spread to Ireland and Scotland no later than the 15th century, as did the common European practice of distilling "aqua vitae" or spirit alcohol primarily for medicinal purposes.[15] The practice of medicinal distillation eventually passed from a monastic setting to the secular via professional medical practitioners of the time, The Guild of Surgeon Barbers.[15] The earliest Irish mention of whisky comes from the seventeenth-century Annals of Clonmacnoise, which attributes the death of a chieftain in 1405 to "taking a surfeit of aqua vitae" at Christmas.[16] In Scotland, the first evidence of whisky production comes from an entry in the Exchequer Rolls for 1494 where malt is sent "To Friar John Cor, by order of the king, to make aquavitae", enough to make about 500 bottles.[17]

James IV of Scotland (r. 1488–1513) reportedly had a great liking for Scotch whisky, and in 1506 the town of Dundee purchased a large amount of whisky from the Guild of Surgeon Barbers, which held the monopoly on production at the time. Between 1536 and 1541, King Henry VIII of England dissolved the monasteries, sending their monks out into the general public. Whisky production moved out of a monastic setting and into personal homes and farms as newly independent monks needed to find a way to earn money for themselves.[14]

The distillation process was still in its infancy; whisky itself was not allowed to age, and as a result tasted very raw and brutal compared to today's versions. Renaissance-era whisky was also very potent and not diluted. Over time whisky evolved into a much smoother drink.

With a licence to distil Irish whiskey from 1608, the Old Bushmills Distillery in Northern Ireland is the oldest licensed whiskey distillery in the world.[18]

In 1707, the Acts of Union merged England and Scotland, and thereafter taxes on it rose dramatically.[19]

After the English Malt Tax of 1725, most of Scotland's distillation was either shut down or forced underground. Scotch whisky was hidden under altars, in coffins, and in any available space to avoid the governmental excisemen or revenuers.[14] Scottish distillers, operating out of homemade stills, took to distilling whisky at night when the darkness hid the smoke from the stills. For this reason, the drink became known as moonshine.[20] At one point, it was estimated that over half of Scotland's whisky output was illegal.[19]

In America, whisky was used as currency during the American Revolution; George Washington operated a large distillery at Mount Vernon. Given the distances and primitive transportation network of colonial America, farmers often found it easier and more profitable to convert corn to whisky and transport it to market in that form. It also was a highly coveted sundry and when an additional excise tax was levied against it in 1791, the Whiskey Rebellion erupted.[21]

The drinking of Scotch whisky was introduced to India in the nineteenth century. The first distillery in India was built by Edward Dyer at Kasauli in the late 1820s. The operation was soon shifted to nearby Solan (close to the British summer capital Shimla), as there was an abundant supply of fresh spring water there.[22]

In 1823, the UK passed the Excise Act, legalizing the distillation (for a fee), and this put a practical end to the large-scale production of Scottish moonshine.[14]

In 1831, Aeneas Coffey patented the Coffey still, allowing for cheaper and more efficient distillation of whisky. In 1850, Andrew Usher began producing a blended whisky that mixed traditional pot still whisky with that from the new Coffey still. The new distillation method was scoffed at by some Irish distillers, who clung to their traditional pot stills. Many Irish contended that the new product was, in fact, not whisky at all.[23]

By the 1880s, the French brandy industry was devastated by the phylloxera pest that ruined much of the grape crop; as a result, whisky became the primary liquor in many markets.[14]

During the Prohibition era in the United States lasting from 1920 to 1933, all alcohol sales were banned in the country. The federal government made an exemption for whisky prescribed by a doctor and sold through licensed pharmacies. During this time, the Walgreens pharmacy chain grew from 20 retail stores to almost 400.[24]

Production

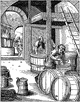

Distillation

A still for making whisky is usually made of copper, since it removes sulfur-based compounds from the alcohol that would make it unpleasant to drink. Modern stills are made of stainless steel with copper innards (piping, for example, will be lined with copper along with copper plate inlays along still walls). The simplest standard distillation apparatus is commonly known as a pot still, consisting of a single heated chamber and a vessel to collect purified alcohol.

Column stills are frequently used in the production of grain whisky and are the most commonly used type of still in the production of bourbon and other American whiskeys. Column stills behave like a series of single pot stills, formed in a long vertical tube. Whereas a single pot still charged with wine might yield a vapour enriched to 40–50% alcohol, a column still can achieve a vapour alcohol content of 95.6%; an azeotropic mixture of alcohol and water.

Aging

Whiskies do not mature in the bottle, only in the cask, so the "age" of a whisky is only the time between distillation and bottling. This reflects how much the cask has interacted with the whisky, changing its chemical makeup and taste. Whiskies that have been bottled for many years may have a rarity value, but are not "older" and not necessarily "better" than a more recent whisky that matured in wood for a similar time. After a decade or two, additional aging in a barrel does not necessarily improve a whisky.

While aging in wooden casks, especially American oak and French oak casks, whisky undergoes six processes that contribute to its final flavor: extraction, evaporation, oxidation, concentration, filtration, and colouration.[25]

Extraction in particular results in whisky acquiring a number of compounds, including aldehydes and acids such as vanillin, vanillic acid, and syringaldehyde.[26]

Packaging

Most whiskies are sold at or near an alcoholic strength of 40% abv, which is the statutory minimum in some countries[8] – although the strength can vary, and cask-strength whisky may have as much as twice that alcohol percentage.

Exports

Whisky is probably the best known of Scotland's manufactured products. Exports have increased by 87% in the decade to 2012 and it contributes over £4.25 billion to the UK economy, making up a quarter of all its food and drink revenues.[27] In 2012, the US was the largest market for Scotch whisky (£655 million), followed by France (£535 million).[28] It is also one of the UK's overall top five manufacturing export earners and it supports around 35,000 jobs.[29] Principal whisky producing areas include Speyside and the Isle of Islay, where there are eight distilleries providing a major source of employment. In many places, the industry is closely linked to tourism, with many distilleries also functioning as attractions worth £30 million GVA each year.[30]

In 2011, 70 per cent of Canadian whisky was exported, with about 60 per cent going to the US, and the rest mostly to Europe and Asia.[31] 15 million cases of Canadian whisky were sold in the US in 2011.[31]

Types

Whisky or whisky-like products are produced in most grain-growing areas. They differ in base product, alcoholic content, and quality.

- Malt whisky is made primarily from malted barley.

- Grain whisky is made from any type of grains.

Malts and grains are combined in various ways:

- Single malt whisky is whisky from a single distillery made from a mash that uses only one particular malted grain. Unless the whisky is described as single-cask, it contains whisky from many casks, and different years, so the blender can achieve a taste recognisable as typical of the distillery. In most cases, single malts bear the name of the distillery, with an age statement and perhaps some indication of some special treatments such as maturation in a port wine cask.

- Blended malt whisky is a mixture of single malt whiskies from different distilleries. If a whisky is labelled "pure malt" or just "malt" it is almost certainly a blended malt whisky. This was formerly called a "vatted malt" whisky.

- Blended whisky is made from a mixture of different types of whisky. A blend may contain whisky from many distilleries so that the blender can produce a flavour consistent with the brand. The brand name may, therefore, omit the name of a distillery. Most Scotch, Irish and Canadian whisky is sold as part of a blend, even when the spirits are the product of one distillery, as is common in Canada.[32] American blended whisky may contain neutral spirits.

- Cask strength (also known as barrel proof) whiskies are rare, and usually only the very best whiskies are bottled in this way. They are bottled from the cask undiluted or only lightly diluted.

- Single cask (also known as single barrel) whiskies are bottled from an individual cask, and often the bottles are labelled with specific barrel and bottle numbers. The taste of these whiskies may vary substantially from cask to cask within a brand.

American

American whiskey is distilled from a fermented mash of cereal grain. It must have the taste, aroma, and other characteristics commonly attributed to whiskey.

Some types of whiskey listed in the United States federal regulations[8] are:

- Bourbon whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 51% corn (maize)

- Corn whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 80% corn

- Malt whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 51% malted barley

- Rye whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 51% rye

- Rye malt whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 51% malted rye

- Wheat whiskey—made from mash that consists of at least 51% wheat

These types of American whiskey must be distilled to no more than 80% alcohol by volume, and barrelled at no more than 125 proof. Only water may be added to the final product; the addition of colouring or flavouring is prohibited. These whiskeys must be aged in new charred-oak containers, except for corn whiskey which does not have to be aged. If it is aged, it must be in uncharred oak barrels or in used barrels. Corn whiskey is usually unaged and sold as a legal version of moonshine.

If one of these whiskey types reaches two years aging or beyond, it is additionally designated as straight, e.g., straight rye whiskey. A whiskey that fulfils all above requirements but derives from less than 51% of any one specific grain can be called simply a straight whiskey without naming a grain.

US regulations recognize other whiskey categories,[8] including:

- Blended whiskey—a mixture that contains a blend of straight whiskeys and neutral grain spirits (NGS), and may also contain flavourings and colourings. The percentage of NGS must be disclosed on the label and may be as much at 80% on a proof gallon basis.

- Light whiskey—produced in the US at more than 80% alcohol by volume and stored in used or uncharred new oak containers

- Spirit whiskey—a mixture of neutral spirits and at least 5% of certain stricter categories of whiskey

Another important labelling in the marketplace is Tennessee whiskey, of which Jack Daniel's, George Dickel, Collier and McKeel,[33] and Benjamin Prichard's[34] are the only brands currently bottled. The main difference defining a Tennessee whiskey is its use of the Lincoln County Process, which involves filtration of the whiskey through charcoal. The rest of the distillation process is identical to bourbon whiskey.[35][36] Whiskey sold as "Tennessee whiskey" is defined as bourbon under NAFTA[37] and at least one other international trade agreement,[38] and is similarly required to meet the legal definition of bourbon under Canadian law.[39]

Australian

Australian whiskies have won global whisky awards and medals, including the World Whiskies Awards and Jim Murray's Whisky Bible "Liquid Gold Awards".[40]

Canadian

By Canadian law Canadian whiskies must be produced and aged in Canada, be distilled from a fermented mash of cereal grain, be aged in wood barrels with a capacity limit of 700 litres (185 US gal; 154 imp gal) for not less than three years, and "possess the aroma, taste and character generally attributed to Canadian whisky".[41] The terms "Canadian Whisky", "Rye Whisky", and "Canadian Rye Whisky" are legally indistinguishable in Canada and do not require any specific grain in their production and are often blends of two or more grains. Canadian whiskies may contain caramel and flavouring in addition to the distilled mash spirits, and there is no maximum limit on the alcohol level of the distillation.[41] To be exported under one of the "Canadian Whisky" designations, a whisky cannot contain more than 9.09% imported spirits.[42]

Canadian whiskies are available throughout the world and are a culturally significant export. Well known brands include Crown Royal, Canadian Club, Seagram's, and Wiser's among others. The historic popularity of Canadian whisky in the United States is partly a result of rum runners illegally importing it into the country during the period of American Prohibition.

Danish

Denmark began producing whisky early in 1974. The first Danish single malt to go on sale was Lille Gadegård from Bornholm, in 2005.[43] Lille Gadegård is a winery as well, and uses its own wine casks to mature whisky.

The second Danish distilled single malt whisky for sale was Edition No.1 from the Braunstein microbrewery and distillery. It was distilled in 2007, using water from the Greenlandic ice sheet, and entered the market in March 2010.[44]

English

There are currently at least six distilleries producing English whisky. Though England is not very well known for making whisky, there were distillers previously operating in London, Liverpool and Bristol until the late 19th century, after which production of English single malt whisky ceased until 2003.[45]

Finnish

There are two working distilleries in Finland and a third one is under construction. Whisky retail sales in Finland are controlled solely by the state alcohol monopoly Alko and advertising of strong alcoholic beverages is banned.[46]

German

German whisky production is a relatively recent phenomenon having only started in the last 30 years. The styles produced resemble those made in Ireland, Scotland and the United States: single malts, blends, wheat, and bourbon-like styles. There is no standard spelling of German whiskies with distilleries using both "whisky" and "whiskey". In 2008 there were 23 distilleries in Germany producing whisky.[47]

Indian

India consumes almost as much whisky as the rest of the world put together.[48] Distilled alcoholic beverages that are labelled as "whisky" in India are commonly blends based on neutral spirits that are distilled from fermented molasses with only a small portion consisting of traditional malt whisky, usually about 10 to 12 percent. Outside India, such a drink would more likely be labelled a rum.[49][50] According to the Scotch Whisky Association's 2013 annual report, "there is no compulsory definition of whisky in India, and the Indian voluntary standard does not require whisky to be distilled from cereals or to be matured."[51][52][53] Ninety percent of the whisky consumed in India is molasses-based,[54] although whisky wholly distilled from malt and other grains, is also manufactured and sold.[55] Amrut, the first single malt whisky produced in India, was launched on 24 August 2004.[56]

Irish

Irish whiskeys are normally distilled three times, Cooley Distillery being the exception as they also double distill.[57] Though traditionally distilled using pot stills, the column still is now used to produce grain whiskey for blends. By law, Irish whiskey must be produced in Ireland and aged in wooden casks for a period of no less than three years, although in practice it is usually three or four times that period.[58] Unpeated malt is almost always used, the main exception being Connemara Peated Malt whiskey. There are several types of whiskey common to Ireland: single malt, single grain, blended whiskey and pure pot still whiskey.

Irish whiskey was once the most popular spirit in the world, though a long period of decline from the late 19th century onwards greatly damaged the industry.[59] Although Scotland sustains approximately 105 distilleries, Ireland has only seven in current operation – only four of which have been operating long enough to have products sufficiently aged for current sale on the market as of 2013, and only one of which was operating before 1975. Irish whiskey has seen a great resurgence in popularity since the late twentieth century, and has been the fastest growing spirit in the world every year since 1990.[59] The current growth rate is at roughly 20% per annum, prompting the construction and expansion of a number of distilleries.

Japanese

The model for Japanese whiskies is the single malt Scotch, although there are also examples of Japanese blended whiskies. The base is a mash of malted barley, dried in kilns fired with a little peat (although considerably less than in Scotland), and distilled using the pot still method. Before 2000, Japanese whisky was primarily for the domestic market and exports were limited. Japanese whiskies such as Suntory and Nikka won many prestigious international awards between 2007 and 2014. Japanese whisky has earned a reputation for quality.[60][61]

Scotch

Scotch whiskies are generally distilled twice, although some are distilled a third time and others even up to twenty times.[62] Scotch Whisky Regulations require anything bearing the label "Scotch" to be distilled in Scotland and matured for a minimum of three years in oak casks, among other, more specific criteria.[63] Any age statement on the bottle, in the form of a number, must reflect the age of the youngest Scotch whisky used to produce that product. A whisky with an age statement is known as guaranteed age whisky.[64] Scotch whisky without an age statement may, by law, be as young as three years old.[65]

The basic types of Scotch are malt and grain, which are combined to create blends. Scotch malt whiskies are divided into five main regions: Highland, Lowland, Islay, Speyside and Campbeltown.[66]

Swedish

Whisky started being produced in Sweden in 1955 by the now defunct Skeppets whisky brand. Their last bottle was sold in 1971.[67] In 1999 Mackmyra Whisky was founded and is today the largest producer and has won several awards including European Whisky of the Year in Jim Murray's 2011 Whisky Bible[68] and the International Wine & Spirits Competition (IWSC) 2012 Award for Best European Spirits Producer of 2012.[69]

Taiwanese

Kavalan is the first and only distillery in Taiwan. In January 2010, one of the distillery's products caused a stir by beating three Scotch whiskies and one English whisky in a blind tasting organised in Leith, Scotland, to celebrate Burns Night.[4][5] The distillery was named by Whisky Magazine as the World Icons of Whisky "Whisky Visitor Attraction of the Year" for 2011, and its products have won several other awards.[3] In 2012, Kavalan's Solist Fino Sherry Cask malt whisky was named "new whisky of the year" by Jim Murray in his guide, Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible.[6] In 2015, Kavalan's Solist Vinho Barrique Single Cask was named the world's best single malt whisky by World Whiskies Awards.[7][8] In 2016, Kavalan Solist Amontillado Sherry Single Cask was named the world's best single malt whisky by World Whisky Awards. [70]

Welsh

Although distillation of whisky in Wales began in Middle Ages there were no commercially operated distilleries during the 20th century. The rise of the temperance movement saw the decline the commercial production of liquor during the 19th century and in 1894 Welsh whisky production ceased. Recently, however, there has been a revival of Welsh whisky.

The revival of Welsh whisky began in the 1990s. Initially a "Prince of Wales" malt whisky was sold as Welsh whisky but was simply blended scotch bottled in Wales. A lawsuit by Scotch distillers ended this enterprise.[71] In 2000, Penderyn Distillery started production of Penderyn single malt whisky. The first bottles went on sale on 1 March 2004, Saint David's Day, and it is now sold worldwide. Penderyn Distillery is located in the Brecon Beacons National Park and is considered to be the smallest distillery in the world.[72]

Other

ManX Spirit from the Isle of Man is distilled elsewhere and re-distilled in the country of its nominal "origin". The ManX distillery takes a previously matured Scotch malt whisky and re-distills it.[73]

In 2010 a Czech whisky was released, the 21-year-old "Hammer Head".[74]

In 2008 at least two distilleries in the traditionally brandy-producing Caucasus region announced their plans to enter the Russian domestic market with whiskies. The Stavropol-based Praskoveysky distillery bases its product on Irish whiskey, while in Kizlyar, Dagestan's "Russian Whisky" announced a Scotch-inspired drink in single malt, blended and wheat varieties.[75]

Destilerías y Crianza del Whisky S.A. is a whisky distillery in Spain. Its eight-year-old Whisky DYC is a combination of malts and spirits distilled from barley aged separately a minimum of eight years in American oak barrels.[76]

Frysk Hynder is a Dutch single malt, distilled and bottled in the Frisian Us Heit Distillery. It is the first single malt produced in the Netherlands.[47]

Buckwheat whisky is produced by Distillerie des Menhirs in Brittany, France, and by several distillers in the United States.

Chemistry

Overview

Whiskies and other distilled beverages, such as cognac and rum, are complex beverages that contain a vast range of flavouring compounds, of which some 200 to 300 are easily detected by chemical analysis. The flavouring chemicals include "carbonyl compounds, alcohols, carboxylic acids and their esters, nitrogen- and sulphur-containing compounds, tannins, and other polyphenolic compounds, terpenes, and oxygen-containing heterocyclic compounds" and esters of fatty acids.[77] The nitrogen compounds include pyridines, picolines and pyrazines.[78]

Flavours from treating the malt

The distinctive smoky flavour found in various types of whisky, especially Scotch, is due to the use of peat smoke to treat the malt.

Flavours from distillation

The flavouring of whisky is partially determined by the presence of congeners and fusel oils. Fusel oils are higher alcohols than ethanol, are mildly toxic, and have a strong, disagreeable smell and taste. An excess of fusel oils in whisky is considered a defect. A variety of methods are employed in the distillation process to remove unwanted fusel oils. Traditionally, American distillers focused on secondary filtration using charcoal, gravel, sand, or linen to remove undesired distillates.

Acetals are rapidly formed in distillates and a great many are found in distilled beverages, the most prominent being acetaldehyde diethyl acetal (1,1-diethoxyethane). Among whiskies the highest levels are associated with malt whisky.[79] This acetal is a principal flavour compound in sherry, and contributes fruitiness to the aroma.[80]

The diketone diacetyl (2,3-butanedione) has a buttery aroma and is present in almost all distilled beverages. Whiskies and cognacs typically contain more of this than vodkas, but significantly less than rums or brandies.[81]

Flavours from oak

Whisky that has been aged in oak barrels absorbs substances from the wood. One of these is cis-3-methyl-4-octanolide, known as the "whisky lactone" or "quercus lactone", a compound with a strong coconut aroma.[82][83]

Commercially charred oaks are rich in phenolic compounds. One study identified 40 different phenolic compounds. The coumarin scopoletin is present in whisky, with the highest level reported in Bourbon whiskey.[84]

In an experiment, whiskey aged 3 years in orbit on the International Space Station tasted and measured significantly different from similar test subjects in gravity on Earth. Particularly, wood extractives were more present in the space samples.[85]

Flavours and colouring from additives

Depending on the local regulations, additional flavourings and colouring compounds may be added to the whisky. Canadian whisky may contain caramel and flavouring in addition to the distilled mash spirits. Scotch whisky may contain added (E150A) caramel colouring, but no other additives. The addition of flavourings is not allowed in American "straight" whiskey, but is allowed in American blends.

Chill filtration

Whisky is often "chill filtered": chilled to precipitate out fatty acid esters and then filtered to remove them. Most whiskies are bottled this way, unless specified as unchillfiltered or non chill filtered. This is done primarily for cosmetic reasons. Unchillfiltered whiskeys often turn cloudy when stored at cool temperatures or when cool water is added to them, and this is perfectly normal.[86]

See also

References

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition: "In modern trade usage, Scotch whisky and Irish whiskey are thus distinguished in spelling; 'whisky' is the usual spelling in Britain and 'whiskey' that in the U.S."

- ↑ New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, entries for "usquebaugh" and "whisky".

- 1 2 3 Cowdery, Charles K. (24 February 2009). "Why Spelling Matters". The Chuck Cowdery Blog.

- 1 2 3 Cowdery, Charles K. (11 February 2009). "New York Times Buckles To Pressure From Scotch Snobs". The Chuck Cowdery Blog.

- ↑ Zandona, Eric; et al. A World Guide to Whisk(e)y Distilleries. Hayward: White Mule Press. ISBN 0983638942.

- ↑ Zandona, Eric. "Whiskey vs Whisky Series". EZdrinking. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Zandona, Eric. "Whiskey vs Whisky: Newspapers & Style Guides". EZdrinking. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits, Title 27 Code of Federal Regulations, Pt. 5.22" (PDF). Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ↑ Martin Levey (1956). "Babylonian Chemistry: A Study of Arabic and Second Millennium B.C. Perfumery", Osiris 12, p. 376-389.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Book A Short History of the Art of Distillation, by Robert James Forbes (year 1948). That book covers distillation in general. For the early history of the distillation of alcohol specifically, search for the word "alcohol" in that book here .

- ↑ Forbes, Robert James (1970). A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ Russell, Inge (2003). Whisky: technology, production and marketing. Academic Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-12-669202-0.

- ↑ The History of Whisky History, The Whisky Guide.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History of Scotch Whisky". Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- 1 2 Whisky: Technology, Production and Marketing: Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages Series p2 Academic Press 2003

- ↑ Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland, p.785, footnote for year 1405. This is likewise in the Annals of Connacht entry for year 1405: Annals of Connacht.

- ↑ Ross, James. Whisky. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 0-7100-6685-6.

- ↑ Ciaran Brady (2000). Encyclopedia of Ireland: an A-Z guide to its people, places, history, and culture. Oxford University Press, p.11

- 1 2 "The History of Whisky".

- ↑ Peggy Trowbridge Filippone, Whiskey History - The history of whisky, About.com.

- ↑ "Kevin R. Kosar, "What the Tea Party Could Learn from the Whiskey Rebellion", adapted from Kevin R. Kosar, Whiskey: A Global History (London: Reaktion Books, 2010)". Alcoholreviews.com. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Whisky in India. Livemint (29 December 2011). Retrieved on 23 December 2013.

- ↑ Magee, Malachy (1980). Irish Whiskey - A 1000 year tradition. O'Brien press. p. 144. ISBN 0-86278-228-7.

- ↑ When Capitalism Meets Cannabis

- ↑ Nickles, Jane, 2015 Certified Specialist of Spirits Study Guide, Society of Wine Educators, p. 23 (2015).

- ↑ Jeffery, John D.E., Aging of Whiskey Spirits in Barrels of Non-Traditional Volume, Master's Thesis, Michigan State University, p. 30 (2012).

- ↑ Scotch Whisky Association. "Scotch Whisky Exports Hit Record Level". Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Record high for food and drink". Government of Scotland. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Scotch Whisky Association. "Scotch Whisky Briefing 2013". Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ The Whisky Barrel. "Scotch Whisky Exports & Visitor Numbers Soar". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- 1 2 Stastna, Kazi (25 May 2013). "Growing appetite for American whisky straining supply". CBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ De Kergommeaux, Davin (2012). Canadian Whisky: The Portable Expert. McClelland & Stewart. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7710-2743-7.

- ↑ Collier and McKeel company web site.

- ↑ "Benjamin Prichard's Tennessee Whiskey". Retrieved January 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Charles K. Cowdery (16 December 2009). "Favorite whiskey myths debunked". The Chuck Cowdery Blog. Retrieved January 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Charles K. Cowdery (21 February 2009). "Tennessee Whiskey Versus Bourbon Whiskey". The Chuck Cowdery Blog. Retrieved January 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "North American Free Trade Agreement Annex 313: Distinctive products". Sice.oas.org. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ SICE - Free Trade Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Chile, Section E, Article 3.15 Distinctive products.

- ↑ "Canada Food and Drug regulations, C.R.C. C.870, provision B.02.022.1". Laws.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Move over Fosters, Whisky Bible toasts Australian drams". Scotsman.com. 8 January 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Canadian Food and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870) - Canadian Whisky, Canadian Rye Whisky or Rye Whisky (B.02.020)". Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ↑ "Terms and Conditions for the Issuance of Certificates of Age and Origin for Distilled Spirits Produced or Packaged in Canada". Canada - Justice Laws Website. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "(in Danish)". Dr.dk. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "''B.T.'', "Dansk whisky destilleres på indlandsis", (in Danish)". Bt.dk. 22 March 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Cornish take on Scotch, BBC news, Thursday, 1 May 2003.

- ↑ ""WITH A DASH OF WATER" Finnish Whisky Culture and its Future". Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- 1 2 MaClean, Charles (2008). Whiskey. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 254–265. ISBN 978-0-7566-3349-3.

- ↑ "Charlemagne: Johnnie won't walk out". Economist.com. 23 February 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Where 'Whisky' Can Be Rum", from The Wall Street Journal, 26 August 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Paul Peachey (3 March 2006). "Battle for the world's largest whisky market -- India". South Africa Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Scotch whisky group threat legal action against Indian blends". The Economic Times. PTI. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "Europe cries foul on Indian whisky". Hindustan Times. PTI. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "Scotch whisky makers threaten action against Indian blends". Business Standard. PTI. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ "India stretches whisky market lead", Beverage Daily, 13 January 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2007

- ↑ Official web site of Amrut Distilleries, Retrieved 25 June 2007

- ↑ Ishani Duttagupta (29 April 2012). "How India's first single malt brand Amrut Distilleries cracked luxury market in West". The Economic Times. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Differences between Scotch and Irish whiskey Archived 5 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Government of Ireland. "Irish Whiskey Act, 1980". Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- 1 2 "Distillers in high spirits as the whiskey sector enters golden era". www.irishtimes.com. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "Awards Won by Nikka Whisky". Nikka.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Nicholas Coldicott (23 May 2008). "Japanese malt scotches rivals". The Japan Times Online.

- ↑ Jackson, Michael (1994). Michael Jackson's Malt Whisky Companion. Dorling Kindersley. p. 12. ISBN 0-7513-0146-9.

- ↑ "ASIL Insight: WTO Protections for Food Geographic Indications". Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- ↑ "What does a whisky's age really mean?".

- ↑ "So, Does Age Matter?" (PDF).

- ↑ "Whisky Regions & Tours". Scotch Whisky Association. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Skeppets whisky - English version". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ↑ "Whisky Bible Award Winners". 2011.

- ↑ "2012 Producer Trophies - IWSC.NET". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Paragraph.co.uk. "Kavalan Solist Amontillado Sherry Single Cask Strength - World's Best Single Cask Single Malt Whisky". World Whiskies Awards. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ↑ Amanda Kelly (8 May 2000). "Welsh will make a rare bit of whiskey". The Independent. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ↑ "Planet Whiskies Welsh Distillery Section". Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ↑ Alan J. Buglass (2011). Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages p.532. John Wiley and Sons

- ↑ "Hammer Head Story". Whisky-pages.com. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ ""Kizlyar" will produce whiskey in Russia". Lenta.ru report (in Russian).

- ↑ "DYC Reserva 8 Años". SPAIN: Licorea.com. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Maarse, H. (1991). Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages. CRC Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8247-8390-5.

- ↑ Belitz, Hans-Dieter; Peter Schieberle; Werner Grosch (2004). Food Chemistry. Springer. p. 936. ISBN 3-540-40818-5.

- ↑ Maarse, H. (1991). Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages. CRC Press. p. 553. ISBN 0-8247-8390-5.

- ↑ "June 2007". The Beer Brewer. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ Maarse, H. (1991). Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages. CRC Press. p. 554. ISBN 0-8247-8390-5.

- ↑ "Aromas and Flavours". Wine-Pages.com. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- ↑ Belitz, Hans-Dieter; Peter Schieberle; Werner Grosch (2004). Food Chemistry. Springer. p. 383. ISBN 3-540-40818-5.

- ↑ Maarse, H. (1991). Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages. CRC Press. p. 574. ISBN 0-8247-8390-5.

- ↑ Grush, Loren. "Whiskey aged in space tastes like throat lozenges and rubbery smoke". The Verge. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ↑ "Chill Filtration". Whiskey Basics. Whisky for Everyone. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

Further reading

- Andrews, Allen (2002). The Whisky Barons. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-897784-84-6.

- Buxton, Ian; Hughes, Paul S. (2014). The Science and Commerce of Whisky. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-150-8.

- Smith, Gavin D. (2009). The A-Z of Whisky (3rd ed.). Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-906476-03-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whisky. |

| Look up whisky or whiskey in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |