O. Henry

| O. Henry | |

|---|---|

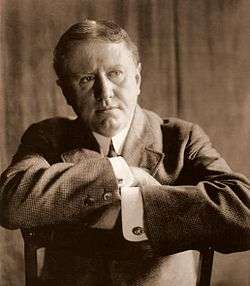

Portrait of O. Henry, by W. M. Vanderweyde, 1909 | |

| Born |

William Sidney Porter September 11, 1862 Greensboro, North Carolina, United States |

| Died |

June 5, 1910 (aged 47) New York City, New York, United States |

| Pen name | O. Henry, Olivier Henry, Oliver Henry[1] |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | American |

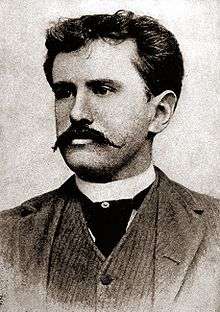

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 – June 5, 1910), known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American short story writer. O. Henry's short stories are known for their surprise endings.

Biography

Early life

William Sidney Porter was born on September 11, 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina. He changed the spelling of his middle name to Sydney in 1898. His parents were Dr. Algernon Sidney Porter (1825–88), a physician, and Mary Jane Virginia Swaim Porter (1833–65). William's parents had married on April 20, 1858. When William was three, his mother died from tuberculosis, and he and his father moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. As a child, Porter was always reading, everything from classics to dime novels; his favorite works were Lane's translation of One Thousand and One Nights, and Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy.[2]

Porter graduated from his aunt Evelina Maria Porter's elementary school in 1876. He then enrolled at the Lindsey Street High School. His aunt continued to tutor him until he was fifteen. In 1879, he started working in his uncle's drugstore and in 1881, at the age of nineteen, he was licensed as a pharmacist. At the drugstore, he also showed off his natural artistic talents by sketching the townsfolk.

Move to Texas

Porter traveled with Dr. James K. Hall to Texas in March 1882, hoping that a change of air would help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed. He took up residence on the sheep ranch of Richard Hall, James' son, in La Salle County and helped out as a shepherd, ranch hand, cook and baby-sitter. While on the ranch, he learned bits of Spanish and German from the mix of immigrant ranch hands. He also spent time reading classic literature. Porter's health did improve and he traveled with Richard to Austin in 1884, where he decided to remain and was welcomed into the home of the Harrells, who were friends of Richard's. Porter took a number of different jobs over the next several years, first as pharmacist then as a draftsman, bank teller and journalist. He also began writing as a sideline.

Porter led an active social life in Austin, including membership in singing and drama groups. He was a good singer and musician. He played both the guitar and mandolin. He became a member of the "Hill City Quartet", a group of young men who sang at gatherings and serenaded young women of the town. Porter met and began courting Athol Estes, then seventeen years old and from a wealthy family. Her mother objected to the match because Athol was ill, suffering from tuberculosis. On July 1, 1887, Porter eloped with Athol to the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot, where they were married.

The couple continued to participate in musical and theater groups, and Athol encouraged her husband to pursue his writing. Athol gave birth to a son in 1888, who died hours after birth, and then a daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, in September 1889. Porter's friend Richard Hall became Texas Land Commissioner and offered Porter a job. Porter started as a draftsman at the Texas General Land Office (GLO) in 1887 at a salary of $100 a month, drawing maps from surveys and fieldnotes. The salary was enough to support his family, but he continued his contributions to magazines and newspapers.

In the GLO building, he began developing characters and plots for such stories as "Georgia's Ruling" (1900), and "Buried Treasure" (1908). The castle-like building he worked in was even woven into some of his tales such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692" (1894).

His job at the GLO was a political appointment by Hall. Hall ran for governor in the election of 1890 but lost. Porter resigned in early 1891 when the new governor, Jim Hogg, was sworn in.

The same year, Porter began working at the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper at the same salary he had made at the GLO. The bank was operated informally and Porter was apparently careless in keeping his books and may have embezzled funds. In 1894, he was accused by the bank of embezzlement and lost his job but was not indicted.

He then worked full-time on his humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which he started while working at the bank. The Rolling Stone featured satire on life, people and politics and included Porter's short stories and sketches. Although eventually reaching a top circulation of 1500, The Rolling Stone failed in April 1895 since the paper never provided an adequate income. However, his writing and drawings had caught the attention of the editor at the Houston Post.

Porter and his family moved to Houston in 1895, where he started writing for the Post. His salary was only $25 a month, but it rose steadily as his popularity increased. Porter gathered ideas for his column by loitering in hotel lobbies and observing and talking to people there. This was a technique he used throughout his writing career.

While he was in Houston, federal auditors audited the First National Bank of Austin and found the embezzlement shortages that led to his firing. A federal indictment followed and he was arrested on charges of embezzlement.

Flight and return

"Porter's father-in-law posted bail to keep him out of jail. He was due to stand trial on July 7, 1896, but the day before, as he was changing trains to get to the courthouse, an impulse hit him. He fled, first to New Orleans and later to Honduras, with which the United States had no extradition treaty at that time. In Honduras, William lived only six months, until January 1897. There he became friends with Al Jennings, a notorious train robber, who later wrote a book about their friendship.[3] He holed up in a Trujillo hotel, where he wrote Cabbages and Kings, in which he coined the term "banana republic" to qualify the country, a phrase subsequently used widely to describe a small, unstable tropical nation in Latin America with a narrowly focused, agrarian economy.[4] Porter had sent Athol and Margaret back to Austin to live with Athol's parents. Unfortunately, Athol became too ill to meet Porter in Honduras as he had planned. When he learned that his wife was dying, Porter returned to Austin in February 1897 and surrendered to the court, pending an appeal. Once again, Porter's father-in-law posted bail so that he could stay with Athol and Margaret.

Athol Estes Porter died from tuberculosis (then known as consumption) on July 25, 1897. Porter had little to say in his own defense, and was found guilty of embezzlement in February 1898, sentenced to five years in prison, and imprisoned on March 25, 1898 at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Porter was a licensed pharmacist and was able to work in the prison hospital as the night druggist. He was given his own room in the hospital wing, and there is no record that he actually spent time in the cell block of the prison. He had fourteen stories published under various pseudonyms while he was in prison, but was becoming best known as "O. Henry", a pseudonym that first appeared over the story "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking" in the December 1899 issue of McClure's Magazine. A friend of his in New Orleans would forward his stories to publishers so that they had no idea that the writer was imprisoned.

Porter was released on July 24, 1901 for good behavior after serving three years. He reunited with his daughter Margaret, now age 11, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Athol's parents had moved after Porter's conviction. Margaret was never told that her father had been in prison—just that he had been away on business.

Later life

Porter's most prolific writing period started in 1902, when he moved to New York City to be near his publishers. While there, he wrote 381 short stories. He wrote a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine. His wit, characterization, and plot twists were adored by his readers, but often panned by critics.

Porter married again in 1907 to childhood sweetheart Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman, whom he met again after revisiting his native state of North Carolina. Sarah Lindsey Coleman was herself a writer and wrote a romanticized and fictionalized version of their correspondence and courtship in her novella Wind of Destiny.[5]

Porter was a heavy drinker, and by 1908 his markedly deteriorating health affected his writing. In 1909, Sarah left him, and he died on June 5, 1910, of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. After funeral services in New York City, he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina. His daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, had a short writing career from 1913 to 1916. She married cartoonist Oscar Cesare of New York in 1916; they were divorced four years later. She died of tuberculosis in 1927 and is buried next to her father.

Stories

O. Henry's stories frequently have surprise endings. In his day, he was called the American answer to Guy de Maupassant. While both authors wrote plot twist endings, O. Henry stories were considerably more playful. His stories are also known for witty narration.

Most of O. Henry's stories are set in his own time, the early 20th century. Many take place in New York City and deal for the most part with ordinary people: clerks, policemen, waitresses, etc.

O. Henry's work is wide-ranging, and his characters can be found roaming the cattle-lands of Texas, exploring the art of the con-man, or investigating the tensions of class and wealth in turn-of-the-century New York. O. Henry had an inimitable hand for isolating some element of society and describing it with an incredible economy and grace of language. Some of his best and least-known work is contained in Cabbages and Kings, a series of stories each of which explores some individual aspect of life in a paralytically sleepy Central American town, while advancing some aspect of the larger plot and relating back one to another.

Cabbages and Kings was his first collection of stories, followed by The Four Million. The second collection opens with a reference to Ward McAllister's "assertion that there were only 'Four Hundred' people in New York City who were really worth noticing. But a wiser man has arisen—the census taker—and his larger estimate of human interest has been preferred in marking out the field of these little stories of the 'Four Million.'" To O. Henry, everyone in New York counted.

He had an obvious affection for the city, which he called "Bagdad-on-the-Subway",[6] and many of his stories are set there—while others are set in small towns or in other cities.

His final work was "Dream", a short story intended for the magazine The Cosmopolitan but left incomplete at the time of his death.[7]

Among his most famous stories are:

- "The Gift of the Magi" about a young couple who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other Christmas gifts. Unbeknownst to Jim, Della sells her most valuable possession, her beautiful hair, in order to buy a platinum fob chain for Jim's watch; while unbeknownst to Della, Jim sells his own most valuable possession, his watch, to buy jeweled combs for Della's hair. The essential premise of this story has been copied, re-worked, parodied, and otherwise re-told countless times in the century since it was written.

- "The Ransom of Red Chief", in which two men kidnap a boy of ten. The boy turns out to be so bratty and obnoxious that the desperate men ultimately pay the boy's father $250 to take him back.

- "The Cop and the Anthem" about a New York City hobo named Soapy, who sets out to get arrested so that he can be a guest of the city jail instead of sleeping out in the cold winter. Despite efforts at petty theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and "mashing" with a young prostitute, Soapy fails to draw the attention of the police. Disconsolate, he pauses in front of a church, where an organ anthem inspires him to clean up his life—and is ironically charged for loitering and sentenced to three months in prison.

- "A Retrieved Reformation", which tells the tale of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, recently freed from prison. He goes to a town bank to case it before he robs it. As he walks to the door, he catches the eye of the banker's beautiful daughter. They immediately fall in love and Valentine decides to give up his criminal career. He moves into the town, taking up the identity of Ralph Spencer, a shoemaker. Just as he is about to leave to deliver his specialized tools to an old associate, a lawman who recognizes him arrives at the bank. Jimmy and his fiancée and her family are at the bank, inspecting a new safe, when a child accidentally gets locked inside the airtight vault. Knowing it will seal his fate, Valentine opens the safe to rescue the child. However, much to Valentine's surprise, the lawman denies recognizing him and lets him go.

- "The Duplicity of Hargraves". A short story about a nearly destitute father and daughter's trip to Washington, D.C.

- "The Caballero's Way", in which Porter's most famous character, the Cisco Kid, is introduced. It was first published in 1907 in the July issue of Everybody's Magazine and collected in the book Heart of the West that same year. In later film and TV depictions, the Kid would be portrayed as a dashing adventurer, perhaps skirting the edges of the law, but primarily on the side of the angels. In the original short story, the only story by Porter to feature the character, the Kid is a murderous, ruthless border desperado, whose trail is dogged by a heroic Texas Ranger. The twist ending is, unusual for Porter, tragic.

Pen name

Porter used a number of pen names (including "O. Henry" or "Olivier Henry") in the early part of his writing career; other names included S.H. Peters, James L. Bliss, T.B. Dowd, and Howard Clark.[8] Nevertheless, the name "O. Henry" seemed to garner the most attention from editors and the public, and was used exclusively by Porter for his writing by about 1902. He gave various explanations for the origin of his pen name.[9] In 1909 he gave an interview to The New York Times, in which he gave an account of it:

It was during these New Orleans days that I adopted my pen name of O. Henry. I said to a friend: "I'm going to send out some stuff. I don't know if it amounts to much, so I want to get a literary alias. Help me pick out a good one." He suggested that we get a newspaper and pick a name from the first list of notables that we found in it. In the society columns we found the account of a fashionable ball. "Here we have our notables," said he. We looked down the list and my eye lighted on the name Henry, "That'll do for a last name," said I. "Now for a first name. I want something short. None of your three-syllable names for me." "Why don’t you use a plain initial letter, then?" asked my friend. "Good," said I, "O is about the easiest letter written, and O it is."A newspaper once wrote and asked me what the O stands for. I replied, "O stands for Olivier, the French for Oliver." And several of my stories accordingly appeared in that paper under the name Olivier Henry.[10]

William Trevor writes in the introduction to The World of O. Henry: Roads of Destiny and Other Stories (Hodder & Stoughton, 1973) that "there was a prison guard named Orrin Henry" in the Ohio State Penitentiary "whom William Sydney Porter ... immortalised as O. Henry".

According to J. F. Clarke it is from the name of the French pharmacist Etienne Ossian Henry, whose name is in the U. S. Dispensary which Porter used working in the prison pharmacy.[11]

Writer and scholar Guy Davenport offers his own hypothesis: "The pseudonym that he began to write under in prison is constructed from the first two letters of Ohio and the second and last two of penitentiary."[9]

Legacy

The O. Henry Award is a prestigious annual prize named after Porter and given to outstanding short stories.

A film was made in 1952 featuring five stories, called O. Henry's Full House. The episode garnering the most critical acclaim was "The Cop and the Anthem" starring Charles Laughton and Marilyn Monroe. The other stories are "The Clarion Call", "The Last Leaf", "The Ransom of Red Chief" (starring Fred Allen and Oscar Levant), and "The Gift of the Magi".

The O. Henry House and O. Henry Hall, both in Austin, Texas, are named for him. O. Henry Hall, now owned by the University of Texas, previously served as the federal courthouse in which O. Henry was convicted of embezzlement.

Porter has elementary schools named for him in Greensboro, North Carolina (William Sydney Porter Elementary)[12] and Garland, Texas (O. Henry Elementary), as well as a middle school in Austin, Texas (O. Henry Middle School).[13] The O. Henry Hotel in Greensboro is also named for Porter.

In 1962, the Soviet Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating O'Henry's 100th birthday. On September 11, 2012, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating the 150th anniversary of O. Henry's birth.[14]

On November 23, 2011, Barack Obama quoted O. Henry while granting pardons to two turkeys named "Liberty" and "Peace".[15] In response, political science professor P. S. Ruckman, Jr., and Texas attorney Scott Henson filed a formal application for a posthumous pardon in September 2012, the same month that the U.S. Postal Service issued its O. Henry stamp.[16] Previous attempts were made to obtain such a pardon for Porter in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan,[17] but no one had ever bothered to file a formal application.[18] Ruckman and Henson argued that Porter deserved a pardon because (1) he was a law-abiding citizen prior to his conviction; (2) his offense was minor; (3) he had an exemplary prison record; (4) his post-prison life clearly indicated rehabilitation; (5) he would have been an excellent candidate for clemency in his time, had he but applied for pardon; (6) by today's standards, he remains an excellent candidate for clemency; and (7) his pardon would be a well-deserved symbolic gesture and more.[16]

Works

- Cabbages and Kings (1904)

- The Four Million (1906), short stories

- The Trimmed Lamp (1907), short stories: "The Trimmed Lamp", "A Madison Square Arabian Night", "The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball", "The Pendulum", "Two Thanksgiving Day Gentlemen", "The Assessor of Success", "The Buyer from Cactus City", "The Badge of Policeman O’Roon", "Brickdust Row", "The Making of a New Yorker", "Vanity and Some Sables", "The Social Triangle", "The Purple Dress", "The Foreign Policy of Company 99", "The Lost Blend", "A Harlem Tragedy", "'The Guilty Party'", "According to Their Lights", "A Midsummer Knight’s Dream", "The Last Leaf", "The Count and the Wedding Guest", "The Country of Elusion", "The Ferry of Unfulfilment", "The Tale of a Tainted Tenner", "Elsie in New York"

- Heart of the West (1907), short stories: "Hearts and Crosses", "The Ransom of Mack", "Telemachus, Friend", "The Handbook of Hymen", "The Pimienta Pancakes", "Seats of the Haughty", "Hygeia at the Solito", "An Afternoon Miracle", "The Higher Abdication", "Cupid à la Carte", "The Caballero's Way", "The Sphinx Apple", "The Missing Chord", "A Call Loan", "The Princess and the Puma", "The Indian Summer of Dry Valley Johnson", "Christmas by Injunction", "A Chaparral Prince", "The Reformation of Calliope"

- The Voice of the City (1908), short stories: "The Voice of the City", "The Complete Life of John Hopkins", "A Lickpenny Lover", "Dougherty’s Eye-opener", "'Little Speck in Garnered Fruit'", "The Harbinger", "While the Auto Waits", "A Comedy in Rubber", "One Thousand Dollars", "The Defeat of the City", "The Shocks of Doom", "The Plutonian Fire", "Nemesis and the Candy Man", "Squaring the Circle", "Roses, Ruses and Romance", "The City of Dreadful Night", "The Easter of the Soul", "The Fool-killer", "Transients in Arcadia", "The Rathskeller and the Rose", "The Clarion Call", "Extradited from Bohemia", "A Philistine in Bohemia", "From Each According to His Ability", "The Memento"

- The Gentle Grafter (1908), short stories: "The Octopus Marooned", "Jeff Peters as a Personal Magnet", "Modern Rural Sports", "The Chair of Philanthromathematics", "The Hand That Riles the World", "The Exact Science of Matrimony", "A Midsummer Masquerade", "Shearing the Wolf", "Innocents of Broadway", "Conscience in Art", "The Man Higher Up", "Tempered Wind", "Hostages to Momus", "The Ethics of Pig"

- Roads of Destiny (1909), short stories: "Roads of Destiny", "The Guardian of the Accolade", "The Discounters of Money", "The Enchanted Profile", "Next to Reading Matter", "Art and the Bronco", "Phœbe", "A Double-dyed Deceiver", "The Passing of Black Eagle", "A Retrieved Reformation", "Cherchez la Femme", "Friends in San Rosario", "The Fourth in Salvador", "The Emancipation of Billy", "The Enchanted Kiss", "A Departmental Case", "The Renaissance at Charleroi", "On Behalf of the Management", "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking", "The Halberdier of the Little Rheinschloss", "Two Renegades", "The Lonesome Road"

- Options (1909), short stories: "'The Rose of Dixie'", "The Third Ingredient", "The Hiding of Black Bill", "Schools and Schools", "Thimble, Thimble", "Supply and Demand", "Buried Treasure", "To Him Who Waits", "He Also Serves", "The Moment of Victory", "The Head-hunter", "No Story", "The Higher Pragmatism", "Best-seller", "Rus in Urbe", "A Poor Rule"

- Strictly Business (1910), short stories: "Strictly Business", "The Gold That Glittered", "Babes in the Jungle", "The Day Resurgent", "The Fifth Wheel", "The Poet and the Peasant", "The Robe of Peace", "The Girl and the Graft", "The Call of the Tame", "The Unknown Quantity", "The Thing’s the Play", "A Ramble in Aphasia", "A Municipal Report", "Psyche and the Pskyscraper", "A Bird of Bagdad", "Compliments of the Season", "A Night in New Arabia", "The Girl and the Habit", "Proof of the Pudding", "Past One at Rooney’s", "The Venturers", "The Duel", "'What You Want'"

- Whirligigs (1910), short stories: "The World and the Door", "The Theory and the Hound", "The Hypotheses of Failure", "Calloway's Code", "A Matter of Mean Elevation", "Girl", "Sociology in Serge and Straw", "The Ransom of Red Chief", "The Marry Month of May", "A Technical Error", "Suite Homes and Their Romance", "The Whirligig of Life", "A Sacrifice Hit", "The Roads We Take", "A Blackjack Bargainer, "The Song and the Sergeant", "One Dollar's Worth", "A Newspaper Story", "Tommy's Burglar", "A Chaparral Christmas Gift", "A Little Local Colour", "Georgia's Ruling", "Blind Man's Holiday", "Madame Bo-Peep of the Ranches"

- Sixes and Sevens (1911), short stories: "The Last of the Troubadours", "The Sleuths", "Witches' Loaves", "The Pride of the Cities", "Holding Up a Train", "Ulysses and the Dogman", "The Champion of the Weather", "Makes the Whole World Kin", "At Arms with Morpheus", "A Ghost of a Chance", "Jimmy Hayes and Muriel", "The Door of Unrest", "The Duplicity of Hargraves", "Let Me Feel Your Pulse", "October and June", "The Church with an Overshot-Wheel", "New York by Camp Fire Light", "The Adventures of Shamrock Jolnes", "The Lady Higher Up", "The Greater Coney", "Law and Order", "Transformation of Martin Burney", "The Caliph and the Cad", "The Diamond of Kali", "The Day We Celebrate"

- Rolling Stones (1912), short stories: "The Dream", "A Ruler of Men", "The Atavism of John Tom Little Bear", "Helping the Other Fellow", "The Marionettes", "The Marquis and Miss Sally", "A Fog in Santone", "The Friendly Call", "A Dinner at ———", "Sound and Fury", "Tictocq", "Tracked to Doom", "A Snapshot at the President", "An Unfinished Christmas Story", "The Unprofitable Servant", "Aristocracy Versus Hash", "The Prisoner of Zembla", "A Strange Story", "Fickle Fortune, or How Gladys Hustled", "An Apology", "Lord Oakhurst's Curse", "Bexar Scrip No. 2692"

- Waifs and Strays (1917), short stories

Notes

- ↑ "The Marquis and Miss Sally", Everybody's Magazine, vol 8, issue 6, June 1903, appeared under the byline "Oliver Henry"

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Henry, O.". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Henry, O.". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - ↑ "Biography: O. Henry". North Carolina History. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ↑ Malcolm D. MacLean (Summer 1968). "O. Henry in Honduras". American Literary Realism, 1870–1910. 1 (3): 36–46. JSTOR 27747601.

- ↑ Current-Garcia, Eugene (1993). O. Henry: A Study of the Short Fiction (First ed.). New York, New York: Twayne Publishers, Macmillan Publishing Co. p. 123. ISBN 0-8057-0859-6.

- ↑ Henry, O. "A Madison Square Arabian Night," from The Trimmed Lamp: "Oh, I know what to do when I see victuals coming toward me in little old Bagdad-on-the-Subway. I strike the asphalt three times with my forehead and get ready to spiel yarns for my supper. I claim descent from the late Tommy Tucker, who was forced to hand out vocal harmony for his pre-digested wheaterina and spoopju." The Trimmed Lamp, Project Gutenberg text

- ↑ Henry, O. "Dream". Read Book Online website. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Porter, William Sydney (O. Henry)". Ncpedia.org.

- 1 2 Guy Davenport, The Hunter Gracchus and Other Papers on Literature and Art, Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 1996.

- ↑ "'O. Henry' on Himself, Life, and Other Things" (PDF), New York Times, April 4, 1909, p. SM9.

- ↑ Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms. BCA. p. 83.

- ↑ Arnett, Ethel Stephens (1973). For Whom Our Public Schools Were Named, Greensboro, North Carolina. Piedmont Press. p. 245.

- ↑ "O. Henry Middle School, Austin, TX". Archive.austinisd.org. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "Celebrating Master Storyteller O. Henry's 150th Birthday Anniversary". U.S. Postal Service. About.usps.com. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ Mark Memmot, "Obama Quotes O. Henry on 'Purely American' Nature of Thanksgiving", The Two-Way, NPR.org. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Jim Schlosser, "Please Mr. President, Pardon O. Henry", O. Henry Magazine, October 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Presidential Pardons: Few from Obama, and None for O. Henry". Go.bloomberg.com. February 21, 2013. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ Edith Evan Asbury, "For O. Henry, a Hometown Festival", The New York Times, April 13, 1985. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

Further reading

- Smith, C. Alphonso (November 1916). "The Strange Case of Sydney Porter And "O. Henry"". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXIII: 54–64. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

External links

- Works by O. Henry at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about O. Henry at Internet Archive

- Works by O. Henry at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- O. Henry Museum

- Biography and stories

- Wall Street Journal article on O. Henry

- O. Henry at the Internet Movie Database

- O. Henry Items on the Portal to Texas History