Victorian Desalination Plant

Entry on Lower Powlett Rd | |

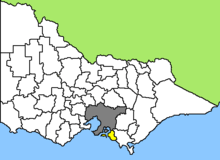

Location of Victorian Desalination Plant | |

| Desalination plant | |

|---|---|

| Location | Dalyston |

| Coordinates | 38°35′16.8″S 145°31′33.6″E / 38.588000°S 145.526000°ECoordinates: 38°35′16.8″S 145°31′33.6″E / 38.588000°S 145.526000°E |

| Estimated output | 410 megalitres (14×106 cu ft) per day |

| Extended output | 550 megalitres (19×106 cu ft) per day |

| Cost | A$5.7 billion[1] - A$19 billion [2] |

| Energy generation offset | Windfarm at Glenthompson (proposed) |

| Technology | Reverse Osmosis (proposed) |

| Percent of water supply | Estimated 33% of Melbourne |

| Operation date | December 2012 |

The Victorian Desalination Plant[3] (also referred to as the Victorian Desalination Project or Wonthaggi desalination plant) is a water desalination plant in Dalyston, on the Bass Coast in southern Victoria, Australia, completed in December 2012. As a rainfall-independent source of water it complements Victoria's existing drainage basins, being a useful resource in times of drought. The plant is a controversial part of Victoria's water system, with ongoing costs of $608 million per year despite virtually no utilisation since completion.[4] The first delivery of 50 gigalitres of water is expected in 2016,[4] a fraction of it's total capacity.

Booked tours are run and plans are underway for Aquasure to open to the public.[5] The gates open daily for public access to the 225-hectare (560-acre) park and 8 kilometres (5 mi) of walking, horse riding and cycling tracks. The plant is located next to Williamsons Beach and the Wonthaggi Wind Farm, Wonthaggi.[6] The intake pipes for the desalination plant are located over 1 kilometre (1⁄2 mi) out to sea.[7]

The desalination plant was promoted through the late 2000s in response to the water restrictions and population growth as being part of the Victorian Government's "Our Water, Our Future" water plan. Marketing material was via print, digital and television advertisements, and included other associated projects such as the North-South Pipeline, the Cardinia Pipeline and a proposed interconnector to Geelong.[8]

The plant site is about 500 metres (1,640 ft) inland and associated infrastructure includes tunnels connecting the plant to marine intake and discharge structures up to 1.2 km (1⁄2 mi) out to sea, an 85-kilometre (55 mi) pipeline to connect the plant to Melbourne's water supply system, and power supply infrastructure for the plant. The plant provides up to 150 gigalitres (5.3×109 cu ft) of additional water per year, with the potential to expand production to 200 gigalitres (7.1×109 cu ft) per year.[9]

The project encountered a campaign of opposition from community groups and local residents, and the Australian Greens. Regular public rallies were conducted on the site and in Melbourne after its proposal. One community group Your Water, Your Say was sent bankrupt following a lost legal case after the group pursued the Victorian Government over lack of reports and consultation. The case centred on initial water requirement figures, feasibility studies and environmental effects reports amongst other issues. More recently, a new opposition group Watershed Victoria, has continued the opposition campaign.

Full production capacity was achieved by the end of 2012, however due to Melbourne's reservoirs being over 80% full the plant was immediately put into standby mode.[2]

Background and project history

The disbanding of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works in 1992 transferred control over the planning process regarding major water and sewerage construction projects to developers. This process came under increased criticism during initial feasibility studies and assessments of Melbourne's water supply and the desalination plant.[10]

By June 2007, the Victorian Government released its water management strategy marketed as Our Water Our Future. As part of the plan, the government announced its intention to develop a seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant to "augment Melbourne's water supply, as well as other regional supply systems."[11]

The total average inflow into Melbourne dams from 1913 to 1996 was 615 gigalitres (2.17×1010 cu ft) per year, whilst average inflow 1997–2009, during the most severe drought ever recorded in Victoria, was 376 gigalitres (1.33×1010 cu ft) per year.[12] Rapid population growth also put pressure on reserves. Reserves in the state's water storage dams decreased from 1998 to 2007 to around a third of maximum capacity.[13][14] Consequently, water restrictions have been in place for several years.[15]

Increased Winter-Spring rains since 2007 took water storages above 40%.[16] In early September 2010, many regions around the state flooded for the first time since the drought began in the late 1990s, water inflow continued into Melbourne's reservoirs defining the end of the drought in Victoria.[16]

Proposal

A two-headed marine structure extending up to 2 km (1 mi) offshore was to be temporarily constructed. It is planned that the plant will take in 480 billion litres (1.1×1011 imp gal; 1.3×1011 US gal) of seawater and pump back 280 billion litres (6.2×1010 imp gal; 7.4×1010 US gal) of saline concentration every year.[17]

Associated infrastructure includes tunnels connecting the plant to marine intake and discharge structures, an 85 km (55 mi) pipeline to connect the plant to Melbourne's existing distribution network at Berwick, and power supply infrastructure for the plant. Water will enter the City water supply system through Cardinia Reservoir.[18]

A windfarm located at Glenthompson is proposed to be built to offset the electricity used by the plant.[19]

The plant was intended to operate at full capacity for a number of years until Melbourne's dams exceed 65% capacity.[20]

Estimated water production is 150 gigalitres (5.3×109 cu ft) of desalinated water per year, potentially capable of providing around a third of Melbourne's annual water consumption based on 2007 consumption levels. It is intended that the water produced will be supplied to Melbourne, Geelong, Western Port and South Gippsland.

When completed, the desalination plant would represent the largest addition to Melbourne's water system since the addition of the Thomson River Dam in 1983.

Environmental effects studies

In August 2008, a 1600-page environmental effects study report was prepared and found that; "...several protected species could be affected by the plant's construction and operation – including the orange-bellied parrot, the growling grass frog and the giant Gippsland earthworm – but none would be left "significantly" worse off.". The community was given 30 business days to respond to the report.[17] Watershed Victoria claimed that this was insufficient time for community groups to analyse the report and prepare submissions.

Contract to build and operate

There were eight tenderers for the contract. Two consortia were short-listed for the construction and operation of the plant – AquaSure (Thiess/Suez) and BassWater (John Holland Group/Veolia Environmental).[21]

On 30 June 2009, the consortium AquaSure, which is made up of Degremont, Macquarie Capital and Thiess, was chosen as the winning bidder.[19] Simultaneously, it was announced that construction was scheduled to commence in late 2009, proposing that water be delivered by late 2011.[18]

Location

Nine sites were included in the "long list" in the feasibility study. These were "short listed" to four (Surf Coast, East of Port Philip Bay, West of Western Port, and Bass Coast). The Bass Coast was chosen as the premium location.[9] Compulsory acquisition notices were issued to affected residents on 25 January 2008.[22]

The final site is a 20-hectare (49-acre) area in Dalyston next to Williamsons Beach on the Bass Coast in south eastern Victoria. It is between Wonthaggi and Kilcunda and near the Powlett River.

The site is located on Bunurong aboriginal land, specifically the Boakoolawal clan who lived in the area south of the Bass River for thousands of years prior to white settlement. Middens containing charcoal and shellfish mark the location of their campsites along the coast.[23] Many significant archaeological artifacts have previously been discovered around the construction site,[24] including Australia’s first dinosaur bone, the Cape Paterson Claw, discovered nearby in 1903 by William Ferguson near what is now Eagles Nest, Bunurong Marine National Park in Inverloch.[25]

The site is located adjacent to the Wonthaggi Wind Farm in Campbell Street, Wonthaggi, which was built in 2005. It is an environmentally friendly wind power station with six turbines.[6] Plans are underway to build a similar, but much larger, wind farm at Glenthompson to offset the electricity used by the Victorian Desalination Plant.[19]

The site location has a strong history of power production, other than the Wonthaggi Wind Farm. The site is located in the Powlett River Coal Fields where the State Coal Mine produced most of the steam-locomotive fuel that serviced the Victorian Railways network, from 1911 until 1978.[26]

Cost

- The capital cost for the project was initially estimated to be $2.9 billion in the initial feasibility study; this was later revised to $3.1 billion[27] and then to $3.5 billion. After the winning bidder was announced it was revised to $4 billion.

- Operating costs are to be charged by a private firm over a 25–30 year period and are estimated to be around $1.5 billion. This cost includes labour, replacement of membranes, chemicals costs and energy, and it was initially estimated at $132 million per annum.[28] Unlike previous water infrastructure works in Melbourne, the plant will be built and operated as a public-private partnership.

A report by the Water Services Association of Australia conducted in 2008, modelling several national water-supply scenarios for 2030, determined that sourcing water supply from seawater desalination was the most energy-intensive. The report predicted that if desalination became the primary source of supplying around 300 litres (66 imp gal; 79 US gal) per person per day, energy usage would rise by 400% above today's levels.[29]

On 12 December 2009 The Age newspaper published details of considerable areas of land made cheaply available to the plant's developers without the value of such land being included in the project's official costs.[30]

- The average water bill for residents living in Melbourne is estimated to rise by around 64% over the next 5 years. Water price plans released by the Essential Services Commission illustrate that metropolitan water providers will charge between 87 per cent and 96 per cent more for water. Water Minister Tim Holding, has stated that; "Melbourne residents need to help pay for major water infrastructure projects, such as the desalination plant and the Sugarloaf (North South) pipeline."[31]

- Comparatively, the Kwinana Desalination Plant in Perth was completed in 2006 and has roughly 30–50% the output of the Wonthaggi plant. It cost $387 million to build and did not include an 85 km (55 mi) pipeline and windfarm.

On completion the plant was immediately placed into standby mode as the reservoirs in Melbourne were over 80% full. However a $1.8 million per day fee is payable to the construction consortium. This minimum fee is payable for a total of 27 years after completion. Even if no water is required the total payment is between $18 and $19 billion.[2]

Energy consumption

The plant is estimated to require 90 MW of electricity to operate. Additional energy will be required to pump the desalinated water from Wonthaggi to Cardinia Reservoir in Melbourne.

A commitment was made to invest in renewable energy to offset the power the plant uses in an attempt to make it carbon neutral.

Construction

The Victorian Government claimed that approximately 4,745 full-time equivalent jobs would be generated by the project over the two-year construction period.[18] Construction work officially began on 6 October 2009.[32] The plant was declared operational in December 2012, approximately one year later than planned.[2]

Media

Construction of the plant was described in an episode of Build It Bigger, which aired on the Discovery Channel and the Science Channel in the United States in 2011.[33]

Opposition

Several community groups as well as the Australian Greens opposed the project. The community group Your Water Your Say was one of the first organised opposition groups and legally pursued the Government in relation to claims the group made concerning the plant. The government pursued legal costs, which sent the group bankrupt.[34]

Public rallies and protests were held both at the site near Wonthaggi and in Melbourne on Spring Street outside the State Parliament buildings throughout 2007, 2008 and 2009.[35] In July 2008, a group of around 50 people conducted a rally on the site, several people were removed from Crown land, none were arrested.[36]

In June 2009, a petition including 3,000 signatories opposing the plant was presented to the Victorian Parliament.[37]

Your Water Your Say v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts

Your Water Your Say (YWYS) opposed the proposal, taking legal action against the Victorian State Government regarding non-disclosure of financial information and lack of environmental studies and reports.[38] As of July 2008 YWYS lost the action, and the Federal Court awarded costs to the State Government estimated to be up to $200,000, effectively rendering the community group broke.[34] YWYS was subsequently disbanded.

In their submission response to the EES, YWYS stated: "The Federal and State Governments are aware that YWYS is unlikely to be in a position to pay its significant legal costs and hence their apparent inability to make a decision on this front can only be interpreted as an attempt to further avoid community scrutiny of this project."[39]

Sharing of private information with private consortia

In December 2009, it was revealed that private information obtained by Victoria Police during surveillance efforts on individuals involved or corresponding with YWYS, Watershed Victoria and other community groups, had been made available to the private consortium building the desalination plant, Aquasure, via a memorandum between the State Government, Victoria Police and Aquasure.[40] Victoria Police responded by explaining that the information would be used to better "manage" future activities and potential "security threats".[40]

Timeline

2007

- 19 June – the Victorian Government announces its intention to develop a seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant on the coast near Wonthaggi. The plant is explained to be part of a water plan marketed as Our Water Our Future.[41]

- 28 December – the Minister for Planning for the Victorian Government determines that the project would require assessment under the Environment Effects Act 1978 and preparations for an Environment Effects Statement (EES) begin.

2008

- 25 January – Compulsory acquisition notices issued to the residents of the proposed site.

- 4 February – the Federal Government determines that the project will have to require approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

- 21 February – 13 March – draft scoping requirements for the EES placed on public exhibition.

- 4 May – final scoping requirements for the EES issued.

- 13 June – Justice Heerey awards costs to the Federal and State Governments a result of the action – Your Water Your Say v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts & Anor; Federal Court Proceeding VID188/2008.

- 5 July – The plant is addressed during the Climate Emergency Rally at various locations in Melbourne.

- 100 m (330 ft) of coastline is landscaped to alter the flow of Powlett River.

- 20 August – 30 September – Environment Effects Statement (EES) released for public comment by the State Government, community given 5 weeks to submit responses to the 1,600-page report.

2009

- 11 January – Planning Minister, Justin Madden, approved a planning scheme amendment to allow for a pilot desalination plant to come into effect on 17 January.[42]

- 30 July – Winning bidder for construction announced.

- 6 October – Construction commenced.

2010

- 4 February – First sections of the new pipeline are laid

2012

- Production and related operations commenced at end of year

- "Zero water order" for financial year 2012–2013 and plant immediately put into standby mode[2]

2035–2045

- Contract for the operation of the plant expected to expire.

Photos

- Construction of pipeline to Melbourne from Wonthaggi desalination plant

- Construction of pipeline to Melbourne from Wonthaggi desalination plant

- Wonthaggi desalination plant construction in progress

- Little Powlett River and rig near Wonthaggi desalination plant

- Little Powlett River estuary near site of Wonthaggi desalination plant

See also

References

- ↑ "Partnerships Victoria: Victorian Desalination Plant". Government of Victoria. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Victorians pay dearly, but not a drop to drink". ABC News. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Victorian Desalination Project". Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Subscribe to the Herald Sun". www.heraldsun.com.au. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ↑ AWA, retrieved 2013-11-04

- 1 2 Wonthaggi Wind Farm, Clean Energy Council, retrieved 2013-10-28

- ↑ Victorian Desalination Plant, retrieved 2013-11-04

- ↑ "The Next Stage of the Government's Plan". Melbourne Water. 16 June 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- 1 2 "Seawater Desalination Plant Feasibility Study – Executive Summary" (PDF). Melbourne Water. June 2007.

- ↑ The Age, 25 September 2008, "Water policy is based on flawed figures", Kenneth Davidson

- ↑ http://www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/34469/Desalination_Plant_EES_Inquiry_Report.pdf

- ↑ Melbourne Water, Annual inflow chart

- ↑ "Answers to your questions on storage levels". Melbourne Water. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ↑ "Government Programs & Action – Background". Melbourne Water. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ↑ "Melbourne water storage levels continue to drop". ABC News. 10 March 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- 1 2 Melbourne Water water storage graph 1997–2010

- 1 2 The Age, 21 August 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Facts Sheet" (PDF). Melbourne Water. June 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Desal consortium selected". ABC News. 30 July 2009.

- ↑ "Dams set to receive major desal boost". ABC News. 11 July 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Davidson, Kenneth (25 June 2009). "Water policy delivers scary possibilities". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. p. 17.

- ↑ "Compulsory acquisition notices" (PDF). Your water, your say. 25 January 2008.

- ↑ Bass Coast Information Centres, retrieved 2013-11-13

- ↑ Parks Victoria, retrieved 2013-11-14

- ↑ The Museum Of Victoria, retrieved 2013-11-14

- ↑ Heritage Victoria, retrieved 2013-11-16

- ↑ "Our Water Our Future – The Next Stage of the Government's Water Plan, Desalination Plant to Deliver 150 billion litres (3.3×1010 imp gal; 4.0×1010 US gal) of Water Per Year". Victorian water Industry association. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ↑ "Seawater Desalination Plant Feasibility Study – Chapter 9a" (PDF). Melbourne Water. June 2007.

- ↑ The Age, 30 August 2008, "Water plant to guzzle energy", Peter Ker

- ↑ Ker, Peter (12 December 2009). "True cost of desal plant concealed". The Age. Melbourne, Australia.

- ↑ ABC, "Water bills set to rise", Fri 7 November 2008 11:52am AEDT.

- ↑ "Desal plant construction gets underway". ABC News. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ "Australian Desalination Plant". The Science Channel. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- 1 2 Ross, Norrie (13 June 2008). "Opponents of Victorian desalination plant must pay costs". Herald Sun. www.news.com.au. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "Desal opponents resume protest at Wonthaggi". ABC News. abc.net.au. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "Protesters met by police at desal site in Wonthaggi". Herald Sun. www.news.com.au. 14 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "Vic Parliament receives Wonthaggi desal petition". ABC News. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ↑ "Action group loses legal challenge over desalination". ABC News. www.abc.net.au. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ↑ "YWYS EES Submission". 30 September 2008.

- 1 2 The Age, Front Page, Saturday 5 December 2009.

- ↑ Our Water Our Future

- ↑ Bass Shire Council, 15 January 2009