Works of Rabindranath Tagore

The Works of Rabindranath Tagore consist of poems, novels, short stories, dramas, paintings, drawings, and music that Bengali poet and Brahmo philosopher Rabindranath Tagore created over his lifetime.

Tagore's literary reputation is disproportionately influenced very much by regard for his poetry; however, he also wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; indeed, he is credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. However, such stories mostly borrow from deceptively simple subject matter — the lives of ordinary people.

Dramas

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen,with his brother Jyotirindranath . Tagore wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — Valmiki Pratibha which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote Visarjan which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. Lastly, Tagore's Chandalika was modeled on an ancient legend describing how a tribal girl lives.

Short stories

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[1] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[2] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[1] Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "Sadhana" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings.[1] There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[3] In particular, such stories as "Kabuliwallah" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atithi" ("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[4] In "The Fruitseller from Kabul", Tagore speaks in first person as town-dweller and novelist who chances upon the Afghani seller. He attempts to distill the sense of longing felt by those long trapped in the mundane and hardscrabble confines of Indian urban life, giving play to dreams of a different existence in the distant and wild mountains: "There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it ... I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest .... ".[5] Many of the other "Galpaguchchha" stories were written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period (1914–1917, again, named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to).[1] Tagore's Golpoguchchho ("Bunch of Stories") remains among the most popular fictional works in Bengali literature. Its continuing influence on Bengali art and culture cannot be overstated; to this day, Golpoguchchho remains a point of cultural reference. Golpoguchchho has furnished subject matter for numerous successful films and theatrical plays, and its characters are among the most well known to Bengalis. The acclaimed film director Satyajit Ray based his film Charulata ("The Lonely Wife") on Nastanirh ("The Broken Nest"). This famous story has an autobiographical element to it, modelled to some extent on the relationship between Tagore and his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi. Ray has also made memorable films of other stories from Golpoguchchho, including Samapti, Postmaster and Monihara, bundling them together as Teen Kanya ("Three Daughters"). Atithi is another poignantly lyrical Tagore story which was made into a film of the same name by another noted Indian film director Tapan Sinha. Tarapada, a young Brahmin boy, catches a boat ride with a village zamindar. It turns out that he has run away from his home and has been wandering around ever since. The zamindar adopts him, and finally arranges a marriage to his own daughter. The night before the wedding Tarapada runs away again. Strir Patra (The letter from the wife) has to be one of the earliest depictions in Bengali literature of such bold emancipation of women. Mrinal is the wife of a typical Bengali middle class man. The letter, written while she is traveling (which constitutes the whole story), describes her petty life and struggles. She finally declares that she will not return to his patriarchical home, stating Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum ("And I shall live. Here, I live").

In Haimanti, Tagore takes on the institution of Hindu marriage. He describes, via Strir Patra, the dismal lifelessness of Bengali women after they are married off, hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle class, and how Haimanti, a sensitive young woman, must — due to her sensitiveness and free spirit — sacrifice her life. In the last passage, Tagore directly attacks the Hindu custom of glorifying Sita's attempted self-immolation as a means of appeasing her husband Rama's doubts (as depicted in the epic Ramayana). Tagore also examines Hindu-Muslim tensions in Musalmanir golpo, which in many ways embodies the essence of Tagore's humanism. On the other hand, Darpaharan exhibits Tagore's self-consciousness, describing a young man harboring literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. Tagore himself, in his youth, seems to have harbored similar ideas about women. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man via his acceptance of his wife's talents. As with many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito provides the Bengalis with one of their more widely used epigrams: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai ("Kadombini died, thereby proved that she hadn't").

Novels

Among Tagore's works, his novels are among the least-acknowledged. These include Noukadubi (1906), Gora (1910), Chaturanga (1916), Ghare Baire (1916), Shesher Kobita (1929), Jogajog (1929) and Char Odhay (1934).

Ghare Baire or The Home and the World, which was also released as the film by Satyajit Ray (Ghare Baire, 1984) examines rising nationalistic feeling among Indians while warning of its dangers, clearly displaying Tagore's distrust of nationalism — especially when associated with a religious element. In some sense, Gora shares the same theme, raising questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity, personal freedom, and religious belief are developed in the context of an involving family story and a love triangle.

Shesher Kobita (translated twice, as Last Poem and as Farewell Song) is his most lyrical novel, containing as it does poems and rhythmic passages written by the main character (a poet). Nevertheless, it is also Tagore's most satirical novel, exhibiting post-modernist elements whereby several characters make gleeful attacks on the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively-renowned poet (named Rabindranath Tagore).

Though his novels remain under-appreciated, they have recently been given new attention through many movie adaptations by such film directors as Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha and Tarun Majumdar. The recent among these is a version of Chokher Bali and Noukadubi (2011 film) directed by Lt. Rituparno Ghosh, which features Aishwariya Rai (in Chokher Bali). A favorite trope of these directors is to employ rabindra sangeet in the film adaptations' soundtracks.s.

Among Tagore's notable non-fiction books are Europe Jatrir Patro ("Letters from Europe") and Manusher Dhormo ("The Religion of Man").

Poetry

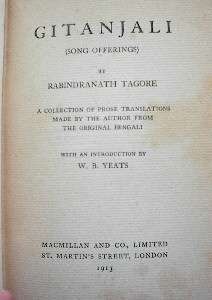

Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry.Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1913 for his book 'Gitanjali' . Song VII from Gitanjali reads as follows:

Original text in Bengali and Roman scripts (গীতাঞ্জলি 127):

|

|

Free-verse translation by Tagore (Gitanjali, verse VII):[6]

|

"My song has put off her adornments. She has no pride of dress and decoration. Ornaments would mar our union; they would come between thee and me; their jingling would drown thy whispers." "My poet's vanity dies in shame before thy sight. O master poet, I have sat down at thy feet. Only let me make my life simple and straight, like a flute of reed for thee to fill with music." |

Besides Gitanjali, other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori ("Golden Boat"), Balaka ("Wild Geese" — the title being a metaphor for migrating souls),[7]

Later, with the development of new poetic ideas in Bengal — many originating from younger poets seeking to break with Tagore's style — Tagore absorbed new poetic concepts, which allowed him to further develop a unique identity. Examples of this include Africa and Camalia, which are among the better known of his latter poems.

The Bangla poet Rabindranath Tagore was the first person (excepting Roosevelt) outside Europe to get the Nobel Prize. He is considered as the pioneer of Bangla literature and culture. The year 1893 AD, was the turn of the century in the Bangla calendar. It was the Bangla year 1300. Tagore wrote a poem then. Its name was ‘The year 1400’. In that poem, Tagore was appealing to a new future poet, yet to be born. He urged in that poem to remember Tagore while he was reading it. He addressed it to that unknown poet who was reading it a century later.

Music

Tagore was also an accomplished musician and painter. Indeed, he wrote some 2500 songs; together, these comprise rabindra sangeet now an integral part of Bengali culture. Yet, Tagore's music is inseparable from his literature, most of which — poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike — became lyrics for his songs. These ran the gamut of human emotion, and are still frequently used to give voice to a wide range of experiences. Such is true of three such works: Bangladesh's Aamaar Sonaar Baanglaa, Sri Lanka's "Sri Lanka Matha" and India's Jana Gana Mana. Tagore thus became the only person ever to have written the national anthems of two nations. Tagore also had an artist's eye for his own handwriting, embellishing the cross-outs and word layouts in his manuscripts with simple artistic leitmotifs.

Art Works

At age sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works — which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[8] — were held throughout Europe. Tagore — who likely exhibited protanopia ("color blindness"), or partial lack of (red-green, in Tagore's case) colour discernment — painted in a style characterised by peculiarities in aesthetic and colouring style. Nevertheless, Tagore took to emulating numerous styles, including that of craftwork by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by Max Pechstein.[9]

[...]Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, play writing and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadishchandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily.‟ He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[10]

Rabindra Chitravali, edited by noted art historian R. Siva Kumar, for the first time makes the paintings of Tagore accessible to art historians and scholars of Rabindranth with critical annotations and comments It also brings together a selection of Rabindranath’s own statements and documents relating to the presentation and reception of his paintings during his lifetime.[12]

The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore was an exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore's paintings to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore. It was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, India and organized with NGMA Delhi as the nodal agency. It consisted of 208 paintings drawn from the collections of Visva Bharati and the NGMA and presented Tagore's art in a very comprehensive way. The exhibition was curated by Art Historian R. Siva Kumar. Within the 150th birth anniversary year it was conceived as three separate but similar exhibitions,and travelled simultaneously in three circuits. The first selection was shown at Museum of Asian Art, Berlin,[13] Asia Society, New York,[14] National Museum of Korea,[15] Seoul, Victoria and Albert Museum,[16] London, The Art Institute of Chicago,[17] Chicago, Petit Palais,[18] Paris, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, National Visual Arts Gallery (Malaysia),[19] Kuala Lumpur, McMichael Canadian Art Collection,[20] Ontario, National Gallery of Modern Art,[21] New Delhi

Adaptations of novels and short stories in film and television

Adaptations in film

- Sacrifice - 1927 (Balidaan) - Nanand Bhojai and Naval Gandhi

- Natir Puja - 1932 - The only film directed by Rabindranath Tagore

- Milan - 1947 (from Nauka Dubi) - Nitin Bose

- Naukadubi - 1947 (from Noukadubi) - Nitin Bose

- Kabuliwala - 1957 - Tapan Sinha

- Kshudhita Pashaan - 1960 - Tapan Sinha

- Charulata - 1964 (Nastanirh) - Satyajit Ray

- Teen Kanya - 1961 - Satyajit Ray

- Kabuliwala - Bimal Roy

- Uphaar - 1971 (from Samapti) - Sudhendu Roy

- Ghare Baire - 1985 - Satyajit Ray

- Lekin... - 1991 (from Kshudhit Pashaan) - Gulzar

- Char Adhyay - 1997 - Kumar Shahani

- Chokher Bali - 2003 - Rituparno Ghosh

- Noukadubi - 2011 - Rituparno Ghosh

- Elar Char Adhyay - 2012 (from Char Adhyay) - Bappaditya Bandyopadhyay

- An obsolete altar - 2013 (from Achalayatan) - Mrigankasekhar Ganguly and Hyash Tanmoy

Adaptations on television

- In 2015, Anurag Basu adapted many short stories of Tagore in a show titled Stories by Rabindranath Tagore, which was aired on EPIC channel. The 26-episode Season 1 was based on many famous short stories such as Chokher Bali, Atithi, Nastanirh, and Kabuliwallah among others.

See also

- Rabindra Sangeet

- Ekla Chalo Re

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Rabindranath Tagore (film)—a biographical documentary by Satyajit Ray.

- Life of Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1901)

- Life of Rabindranath Tagore (1901–1932)

- Life of Rabindranath Tagore (1932–1941)

- Political views of Rabindranath Tagore

Citations

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rabindranath Tagore |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Bengali Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- 1 2 3 4 (Chakravarty 1961, p. 45).

- ↑ (Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 265).

- ↑ (Chakravarty 1961, pp. 45–46)

- ↑ (Chakravarty 1961, p. 46)

- ↑ (Chakravarty 1961, pp. 48–49)

- ↑ (Tagore 1977, p. 5).

- ↑ (Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 1)

Oh youth, oh the tender,

oh green, oh unknowing,

hit the bodies of the halfdead to bring them back to life. - ↑ (Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 222).

- ↑ (Dyson 2001).

- ↑ R. Siva Kumar 2011.

- ↑ R. Siva Kumar 2012.

- ↑ http://rabindranathtagore-150.gov.in/chitravali.html

- ↑ "Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Kalender". Smb.museum. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Current Exhibitions Upcoming Exhibitions Past Exhibitions. "Rabindranath Tagore: The Last Harvest | New York". Asia Society. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Exhibitions | Special Exhibitions". Museum.go.kr. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Painter - Victoria and Albert Museum". Vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ http://www.artic.edu/sites/default/files/press_pdf/Tagore.pdf

- ↑ "Le Petit Palais - Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) - Paris.fr". Petitpalais.paris.fr. 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Welcome to High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia)". Indianhighcommission.com.my. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "McMichael Canadian Art Collection > The Last Harvest: Paintings by Rabindranath Tagore". Mcmichael.com. 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ http://www.ngmaindia.gov.in/pdf/The-Last-Harvest-e-INVITE.pdf

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Works by Rabindranath Tagore. |

- Chakravarty, A (1961), A Tagore Reader, Beacon Press, ISBN 0-8070-5971-4.

- Dutta, K; Robinson, A (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-14030-4.

- Dutta, K (editor); Robinson, A (editor) (1997), Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-16973-6.

- Som, KK (2001), "Rabindranath Tagore and his World of Colours", Parabaas, retrieved April 1, 2006.

- Tagore, R (1977), Collected Poems and Plays of Rabindranath Tagore, Macmillan Publishing, ISBN 0-02-615920-1.