Yellowdog Updater, Modified

| |

|

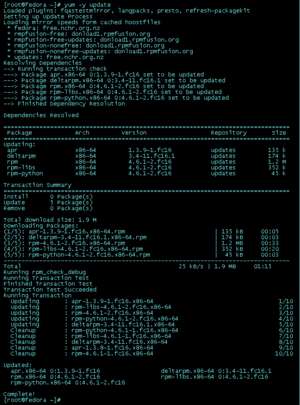

Yum running an update on Fedora 16 | |

| Developer(s) | Seth Vidal |

|---|---|

| Repository |

yum |

| Written in | Python[1] |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type | Package management system |

| License | GPL v2 |

| Website |

yum |

The Yellowdog Updater, Modified (yum) is an open-source command-line package-management utility for computers running the Linux operating system using the RPM Package Manager.[2] Though yum has a command-line interface, several other tools provide graphical user interfaces to yum functionality.

Yum allows automatic updates, package and dependency management, on RPM-based distributions.[3] Like the Advanced Package Tool (APT) from Debian, yum works with software repositories (collections of packages), which can be accessed locally[4] or over a network connection.

Under the hood, yum depends on RPM, which is a packaging standard for digital distribution of software, which automatically uses hashes and digisigs to verify the authorship and integrity of said software; unlike some app stores, which serve a similar function, neither yum nor RPM provide built-in support for proprietary restrictions on copying of packages by endusers. Yum is implemented as libraries in the Python programming language, with a small set of programs that provide a command-line interface.[5] GUI-based wrappers such as Yum Extender (yumex) also exist.[6] A rewrite of yum based on libsolv named DNF is currently being developed and replaced yum as the default package manager in Fedora 22.[7]

History

As a full rewrite of its predecessor tool, Yellowdog Updater (YUP), yum evolved primarily in order to update and manage Red Hat Linux systems used at the Duke University Department of Physics. Seth Vidal and Michael Stenner did the original development of yum at Duke, while yup was originally developed and maintained by Dan Burcaw, Bryan Stillwell, Stephen Edie, and Troy Bengegerdes of Yellow Dog Linux.[2] In 2003 Robert G. Brown at Duke published documentation.[5] Subsequent adopters included Red Hat Enterprise Linux,[8] Fedora, CentOS, and many other RPM-based Linux distributions, including Yellow Dog Linux itself, where it replaced the original YUP utility, which had its last update on SourceForge in 2001.[9] By 2005, it was estimated to be available on over half of the Linux market,[1] and by 2007 yum was considered "the tool of choice"[10] for RPM-based Linux distributions.

The GNU General Public License of yum allows the free and open-source software to be freely distributed and modified without any royalty, if other terms of the license are followed.[2] Vidal continued to contribute to yum until he died in a Durham, North Carolina bicycle accident on 8 July 2013.[11][12][13]

Yum aimed to address both the perceived deficiencies in the old APT-RPM,[14] and restrictions of the Red Hat up2date package management tool. yum superseded up2date in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 and later.[15] Some authors refer to it as the Yellowdog Update Manager, or suggest that "Your Update Manager" would be more appropriate.[16][17]

A basic knowledge of yum is often included as a requirement for Linux system-administrator certification.[3]

Operations

yum can perform operations such as:

- installing packages

- deleting packages

- updating existing installed packages

- listing available packages[18]

- listing installed packages[18]

Extensions

The 2.x versions of yum feature an additional interface for programming extensions in Python that allows the behavior of yum to be altered. Certain plug-ins are installed by default.[19] A commonly installed[20] package yum-utils, contains commands which use the yum API, and many plugins.

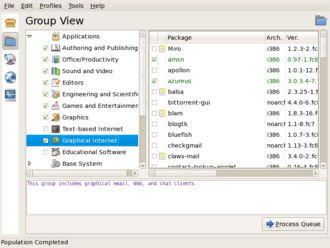

Graphical user interfaces, known as "front-ends", allow easier use of yum. PackageKit and Yum Extender (yumex) are two examples.[6]

Metadata

Information about packages (as opposed to the packages themselves) is known as metadata. These metadata are combined with information in each package to determine (and resolve, if possible) dependencies among the packages. The hope is to avoid a situation known as dependency hell. A separate tool, createrepo, sets up yum software repositories, generating the necessary metadata in a standard XML format (and the SQLite metadata if given the -d option).[21][22] The mrepo tool (formerly known as Yam) can help in the creation and maintenance of repositories.[23]

Yum's XML repository, built with input from many other developers, quickly became the standard for RPM-based repositories.[22] Besides the distributions that use Yum directly, SUSE Linux 10.1[24] added support for Yum repositories in YaST, and the Open Build Service repositories use the yum XML repository format metadata.[22]

Yum automatically synchronizes the remote meta data to the local client, with other tools opting to synchronize only when requested by the user. Having automatic synchronization means that yum cannot fail due to the user failing to run a command at the correct interval.[25][26]

See also

References

- 1 2 Jang, Michael H. (14 December 2005). "Chapter 7 – Setting Up a yum Repository". Linux Patch Management: Keeping Linux Systems Up to Date (PDF). Prentice Hall Professional.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Robert G. "Yum (Yellowdog Updater, Modified) HOWTO - Introduction". Duke Physics. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- 1 2 Shields, Ian (11 May 2010). "RPM and YUM package management". Learn Linux, 101. IBM. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "Creating a Local Yum Repository Using an ISO Image". Oracle. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- 1 2 Brown, Robert G. (17 December 2003). "YUM: Yellowdog Updater, Modied" (PDF). Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Yum Extender". Yumex Homepage. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Matthew (11 June 2014). "Board Meeting, Rawhide Rebuilt, Firewall Debate, ARM 64, and DNF as Yum Replacement (5tFTW 2014-06-10)". Fedora Magazine. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ "Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Deployment Guide. Chapter 6: Yum". Red Hat. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Yellow Dog Update Program". SourceForge repository. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Fusco, John. The Linux Programmer's Toolbox. Pearson Education. ISBN 9780132703048.

- ↑ "Seth Vidal, creator of "yum" open source software, killed in bike accident off Hillandale Rd.". Durham io: The Daily Durham. 9 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ "Thank you, Seth Vidal". Red Hat. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Bort, Julie (9 July 2013). "36-Year-Old Open Source Guru Seth Vidal Has Been Tragically Killed". Business Insider. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Murphy, David (23 July 2004). "How to run your own yum repository". Linux Foundation. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "What are the yum equivalents of up2date and rpm common tasks on Red Hat Enterprise Linux?". Red Hat.

- ↑ Sweeney, Michael (2005). Network Security Using Linux. p. 84. ISBN 9781411621770.

- ↑ Negus, Christopher; Bresnahan, Christine (2012). Linux Bible. John Wiley & Sons. p. 598. ISBN 9781118286906.

- 1 2 Jang, Michael H. (2006). Linux Patch Management: Keeping Linux Systems Up to Date. Bruce Perens' Open Source series. Prentice Hall Professional. p. 199. ISBN 9780132366755. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Yum Plug-ins". Red Hat. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "Maintaining yum". CentOS. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "createrepo(8)". Linux manual page. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Standards Rpm Metadata". openSUSE. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "mrepo". Freecode. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ "SUSE Linux 10.1 Alpha 2 is ready". Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Schmitz, Dietrich T. "YUM vs. APT: Which is Best?".

- ↑ "'Linux Advocates' Throws in the Towel i.e. previous link is dead". FOSS Force.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yum Extender. |

- Official website

- Managing packages with yum – Describes how to use yum to manage packages

- Yum documentation in Fedora

- Yum documentation in CentOS

- Yum documentation in Scientific Linux