İske imlâ alphabet

| İske imlâ | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Languages | Tatar, experimental usage for the Bashkir |

Time period | Circa 1870 to 1920 |

Parent systems | |

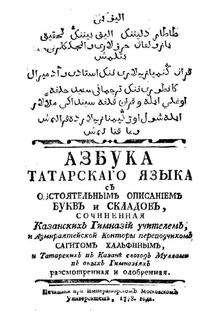

İske imlâ (Tatar: иске имля "Old Orthography", pronounced [isˈke imˈlʲæ]) is a variant of the Arabic script, used for the Tatar language before 1920 and the Old Tatar language. This alphabet can be referred to as old only to contrast it with Yaña imlâ.

Additional characters that could not be found in Arabic and Persian were borrowed from the Chagatai language. The final alphabet was reformed by Qayum Nasiri in the 1870s. In 1920, it was replaced by the Yaña imlâ (which was not an Abjad, but derived from the same source).

This alphabet is currently used by Chinese Tatars, who speak an archaic Tatar language.

Description

Use of the Arabic script for Tatar was linked to Pan Islam and anti Sovietism, with the old traditional class promoting Arabic script in opposition to the Soviets.[1]

Based on the standard Arabic alphabet, İske imlâ reflected all vowels in the beginning and end of a word, and back vowels in the middle of a word with letters, but front vowels in the middle of a word, as in most Arabic alphabets, were optionally reflected using harakat (diacritics on top of or below consonants). Just as in standard Arabic orthography, letters Alif, Yāʼ, and Waw were used to represent all vowels in the beginning and end of a word, and back vowels in the middle of a word, with various harakat on top or below them, and in these cases the letters actually denoted a vowel. The same harakat that combined with the afore-mentioned letters to make vowels were used in the middle of a word on top of or below a consonant to represent a front vowel. However, the following pairs/triplets of Tatar vowels were represented by the same harakat, because Arabic language only uses 3 of them to represent vowels which can be either back or front depending on whether they are applied to Alif, Yāʼ, and Waw or another letter (plus Alif madda represents a [ʔæː] in the beginning of a word): ı, e, í and i were represented with kasra, whereas ö and ü were represented with damma. O and U also looked the same, but being back vowels, they were represented with the help of Alif, and Waw, and thus were distinct from ö and ü. Fatha represented only one vowel. While the user had to make a conversion of writing into pronunciation, somewhat akin to English, this allowed for more similar orthography between Turkic languages, because words looked more similar even when vowels vary, such as in cases of variations like ö to ü, o to u, or e to i.

Yaña imlâ added separate letters for vowels, and thus broke out with standard Arabic alphabets, but spelling followed no standard convention. During that period, the Tatar language had no borrowed vowels and consonates, so Arab loanwords were pronounced using the closest Tatar consonants (see table). European and Russian loanwords were pronounced according to how they could be written with the İske imlâ, so that, for example, "equator" was spelled "ikwatur".

The alphabet

| name | Initial | Medial | Final | Stand-alone | modern Latin Tatar alphabet | modern Cyrillic Tatar alphabet | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | älif | آ | ﺎ | ﺎ | آ | a | а | |

| 2 | älif | ﺍ | ﺍ | ﺎ | ﺍ | ä | ә | |

| 3 | bi | ﺑ | ﺒ | ﺐ | ﺏ | b | б | |

| 4 | pi | ﭘ | ﭙ | ﭗ | ﭖ | p | п | |

| 5 | ti | ﺗ | ﺘ | ﺖ | ﺕ | t | т | |

| 6 | si | ﺛ | ﺜ | ﺚ | ﺙ | s | с | in Bashkir language ҫ |

| 7 | cim | ﺟ | ﺠ | ﺞ | ﺝ | c | җ | |

| 8 | çi | ﭼ | ﭽ | ﭻ | ﭺ | ç | ч | |

| 9 | xi | ﺣ | ﺤ | ﺢ | ﺡ | x | х | |

| 10 | xı | ﺧ | ﺨ | ﺦ | ﺥ | x | х | |

| 11 | däl | ﺩ | ﺪ | ﺪ | ﺩ | d | д | |

| 12 | zäl | ﺫ | ﺬ | ﺬ | ﺫ | z | з | in Bashkir language and some dialects ҙ |

| 13 | ra | ﺭ | ﺮ | ﺮ | ﺭ | r | р | |

| 14 | zi | ﺯ | ﺰ | ﺰ | ﺯ | z | з | |

| 15 | jé | ﮊ | ﮋ | ﮋ | ﮊ | j | ж | |

| 16 | sin, sen | ﺳ | ﺴ | ﺲ | ﺱ | s | с | |

| 17 | şın | ﺷ | ﺸ | ﺶ | ﺵ | ş | ш | |

| 18 | sad | ﺻ | ﺼ | ﺺ | ﺹ | s | с | |

| 19 | dad, z’ad | ﺿ | ﻀ | ﺾ | ﺽ | d, z | д, з | |

| 20 | tí | ﻃ | ﻄ | ﻂ | ﻁ | t | т | |

| 21 | zí | ﻇ | ﻈ | ﻆ | ﻅ | z | з | |

| 22 | ğäyn | ﻋ | ﻌ | ﻊ | ﻉ | ğ | г(ъ) | alternative Cyrillic transcription: ғ |

| 23 | ğayn | ﻏ | ﻐ | ﻎ | ﻍ | ğ | г(ъ) | alternative Cyrillic transcription: ғ |

| 24 | fi | ﻓ | ﻔ | ﻒ | ﻑ | f | ф | |

| 25 | qaf | ﻗ | ﻘ | ﻖ | ﻕ | q | к(ъ) | alternative Cyrillic transcription: қ |

| 26 | kaf | ﻛ | ﻜ | ﻚ | ﮎ | k | к | |

| 27 | gaf | ﮔ | ﮕ | ﮓ | ﮒ | g | г | |

| 28 | eñ | ﯕ | ﯖ | ﯔ | ﯓ | ñ | ң | Initial form was never used due phonetic reasons |

| 29 | läm | ﻟ | ﻠ | ﻞ | ﻝ | l | л | |

| 30 | mim | ﻣ | ﻤ | ﻢ | ﻡ | m | м | |

| 31 | nün | ﻧ | ﻨ | ﻦ | ﻥ | n | н | |

| 32 | ha | ﻫ | ﻬ | ﻪ | ﻩ | h | һ | |

| 33 | waw | ﻭ | ﻮ | ﻮ | ﻭ | w, u, o | в, у, о | alternative Cyrillic transcription: ў, у, о |

| 34 | vaw | ﯞ | ﯟ | ﯟ | ﯞ | v | в | corresponds to в in Bashkir alphabet |

| 35 | ya | ﻳ | ﻴ | ﻰ | ﻯ | y, í, i | й, и, ый |

See also

References

- ↑ Minglang Zhou (2003). Multilingualism in China: the politics of writing reforms for minority languages, 1949-2002. Volume 89 of Contributions to the sociology of language (illustrated ed.). Published Walter de Gruyter. p. 174. ISBN 3-11-017896-6. Retrieved 2011-01-01.