I

|

I (named i /ˈaɪ/, plural ies)[1] is the ninth letter and the third vowel in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

History

| Egyptian hieroglyph ꜥ | Phoenician Yodh |

Etruscan I |

Greek Iota | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In the Phoenician alphabet, the letter may have originated in a hieroglyph for an arm that represented a voiced pharyngeal fricative (/ʕ/) in Egyptian, but was reassigned to /j/ (as in English "yes") by Semites, because their word for "arm" began with that sound. This letter could also be used to represent /i/, the close front unrounded vowel, mainly in foreign words.

The Greeks adopted a form of this Phoenician yodh as their letter iota (⟨Ι, ι⟩) to represent /i/, the same as in the Old Italic alphabet. In Latin (as in Modern Greek), it was also used to represent /j/ and this use persists in the languages that descended from Latin. The modern letter 'j' originated as a variation of 'i', and both were used interchangeably for both the vowel and the consonant, coming to be differentiated only in the 16th century.[2] The dot over the lowercase 'i' is sometimes called a tittle. In the Turkish alphabet, dotted and dotless I are considered separate letters, representing a front and back vowel, respectively, and both have uppercase ('I', 'İ') and lowercase ('ı', 'i') forms.

Use in writing systems

English

In Modern English spelling, ⟨i⟩ represents several different sounds, either the diphthong /aɪ/ ("long" ⟨i⟩) as in kite, the short /ɪ/ as in bill, or the ⟨ee⟩ sound /iː/ in the last syllable of machine. The diphthong /aɪ/ developed from Middle English /iː/ through a series of vowel shifts. In the Great Vowel Shift, Middle English /iː/ changed to Early Modern English /ei/, which later changed to /əi/ and finally to the Modern English diphthong /aɪ/ in General American and Received Pronunciation. Because the diphthong /aɪ/ developed from a Middle English long vowel, it is called "long" ⟨i⟩ in traditional English grammar.

The letter ⟨i⟩ is the fifth most common letter in the English language.[3]

The English first-person singular nominative pronoun is "I", pronounced /aɪ/ and always written with a capital letter. This pattern arose for basically the same reason that lowercase ⟨i⟩ acquired a dot: so it wouldn't get lost in manuscripts before the age of printing:

The capitalized “I” first showed up about 1250 in the northern and midland dialects of England, according to the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology.Chambers notes, however, that the capitalized form didn’t become established in the south of England “until the 1700s (although it appears sporadically before that time).

Capitalizing the pronoun, Chambers explains, made it more distinct, thus “avoiding misreading handwritten manuscripts.”[4]

Other languages

In many languages' orthographies, ⟨i⟩ is used to represent the sound /i/ or, more rarely, /j/.

| Language | Pronunciation in IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| French | /i/ | See French orthography. |

| German | /j/, /iː/, /i/ | See German orthography. |

| Italian | /i/ | Pronounced as long [iː] in stressed and open syllables, [i] when in a closed stressed syllable or unstressed. See Italian orthography. |

Other uses

The Roman numeral Ⅰ represents the number 1.[5][6]

Forms and variants

In some sans serif typefaces, the uppercase letter I, 'I' may be difficult to distinguish from the lowercase letter L, 'l', the vertical bar character '|', or the digit one '1'. In serifed typefaces, the capital form of the letter has both a baseline and a cap-height serif, while the lowercase L has generally a hooked ascender and a baseline serif.

The uppercase I does not have a dot (tittle) while the lowercase i has one in most Latin-derived alphabets. However, some schemes, such as the Turkish alphabet, have two kinds of I: dotted (İi) and dotless (Iı).

The uppercase I has two kinds of shapes, with serifs (![]() ) and without serifs (

) and without serifs (![]() ). Usually these are considered equivalent, but they are distinguished in some extended Latin alphabet systems such as the 1978 version of the African reference alphabet. In that system, the former is the uppercase counterpart of ɪ and the latter is the counterpart of 'i'.

). Usually these are considered equivalent, but they are distinguished in some extended Latin alphabet systems such as the 1978 version of the African reference alphabet. In that system, the former is the uppercase counterpart of ɪ and the latter is the counterpart of 'i'.

Computing codes

| Character | I | i | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I | LATIN SMALL LETTER I | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 73 | U+0049 | 105 | U+0069 |

| UTF-8 | 73 | 49 | 105 | 69 |

| Numeric character reference | I | I | i | i |

| EBCDIC family | 201 | C9 | 137 | 89 |

| ASCII1 | 73 | 49 | 105 | 69 |

- 1Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings

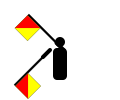

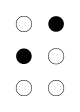

Other representations

Related characters

Descendants and related characters in the Latin alphabet

- I with diacritics: Ị ị Ĭ ĭ Î î Ǐ ǐ Ɨ ɨ Ï ï Í í Ì ì Į į Ī ī Ĩ ĩ

- İ i and I ı : Latin dotted and dotless letter i

- IPA-specific symbols related to I: ɪ ɨ

Ancestors and siblings in other alphabets

- 𐤉 : Semitic letter Yodh, from which the following symbols originally derive

- Ι ι: Greek letter Iota, from which the following letters derive

- Ⲓ ⲓ : Coptic letter Yota

- І і : Cyrillic letter soft-dotted I

- 𐌉 : Old Italic I, which is the ancestor of modern Latin I

- ᛁ : Runic letter isaz, which probably derives from old Italic I

- 𐌹 : Gothic letter iiz

- Ι ι: Greek letter Iota, from which the following letters derive

See also

References

- ↑ Brown & Kiddle (1870) The institutes of English grammar, p. 19.

Ies is the plural of the English name of the letter; the plural of the letter itself is rendered I's, Is, i's, or is. - ↑ "The Latin Alphabet". du.edu.

- ↑ "Frequency Table". cornell.edu. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ O’Conner, Patricia T.; Kellerman, Stewart (2011-08-10). "Is capitalizing "I" an ego thing?". Grammarphobia. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Gordon, Arthur E. (1983). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. University of California Press. p. 44. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ King, David A. (2001). The Ciphers of the Monks. p. 282.

In the course of time, I, V and X became identical with three letters of the alphabet; originally, however, they bore no relation to these letters.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article I. |