Raid on Deerfield

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1704 Raid on Deerfield (or the Deerfield Massacre[9]) occurred during Queen Anne's War on February 29 when French and Native American forces under the command of Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville attacked the English frontier settlement at Deerfield, Massachusetts, just before dawn, burning part of the town, killing 47 villagers, and taking 112 settlers captive to Canada, of whom 60 were later redeemed.

Typical of the small scale frontier conflict in Queen Anne's War, the French-led raid relied on a coalition of French soldiers and a variety of Indian populations, including in the force of about 300 a number of Pocumtucs who had once lived in the Deerfield area. The diversity of personnel, motivations, and material objectives involved in the raid meant that it did not achieve full surprise when they entered the palisaded village. The defenders of some fortified houses in the village successfully held off the raiders until arriving reinforcements prompted their retreat. However, the raid was a clear victory for the French coalition that aimed to take captives and unsettle English colonial frontier society. More than 100 captives were taken, and about 40 percent of the village houses were destroyed.

Although predicted, the raid shocked New England colonists, further antagonized relations with the French and their Native American allies, and led to more community war preparedness in frontier settlements. The raid has been immortalized as a part of the early American frontier story, principally due to the account of one of its captives, the Rev. John Williams. He and his family were forced to make the long overland journey to Canada. His young daughter Eunice was adopted by a Mohawk family; she became assimilated and married a Mohawk man. Williams' account, The Redeemed Captive, was published in 1707 and was widely popular in the colonies.

Background

At the time of the arrival of European colonists in the middle reaches of the Connecticut River valley (where it presently flows through the state of Massachusetts), the area that is now Deerfield, Massachusetts was inhabited by the Algonquian-speaking Pocomtuc nation.[10] In the early 1660s, the Pocumtuc were shattered as a nation due to conflict with the aggressive Mohawk nation.[11] In 1665 villagers from the eastern Massachusetts town of Dedham were given a grant in the area, and acquired land titles of uncertain legality from a variety of Pocumtuc individuals. A village, at first called Pocumtuck, but later Deerfield, was established in the early 1670s.[12] Located in a relatively isolated position on the edge of English settlement, Deerfield was involved in the inevitable frontier conflict between groups of other European settlers and Native Americans.[13]

The colonial outpost was a traditional New England subsistence farming community and the majority of Deerfield's settlers were young families who had moved west in the search of land; it was not an outpost of rugged, frontier individuals, but English colonial families. Women were not a minority in the frontier community. Rather, women's labor was essential to the survival of the settlement and its male inhabitants.[14]

Previous raids on Deerfield

By 1675 the village had grown to number about 200 individuals. In that year, conflict between colonists and Indians in southern New England erupted into what is now known as King Philip's War.[15] The war involved all of the New England colonies, and resulted in the destruction or severe reduction and pacification of most of its Indian nations as well as inflicting many casualties on the New England colonists.[16]

Deerfield was evacuated in September 1675 after a coordinated series of attacks culminating in the Battle of Bloody Brook resulted in the death of about half the village's adult males. The abandoned village, one of several in the Connecticut River valley abandoned by the English, was briefly reoccupied by the warring Indians.[17][18] The colonists regrouped, and in 1676 a force of mostly local colonists slaughtered an Indian camp at a site then called Peskeompscut. It is now called Turner's Falls after William Turner, the English leader who was slain in the action.[19]

Ongoing raids by the Mohawk forced many of the remaining Indians to retreat north to French-controlled Canada or to the west.[20] Those going west joined other tribes that had formed a peace of sorts with the authorities of the Province of New York. During King William's War (1688–1697), Deerfield was not subjected to major attacks, but the community had 12 residents killed in a series of ambushes and other incidents. Supposedly friendly Indians who were recognized as Pocumtuc were also seen passing through the area, and some of them claimed to have participated in attacks on other frontier communities.[21]

Attacks on the frontier communities of what is now southern Maine in the Northeast Coast Campaign (1703) again put Deerfield residents on the alert. In response to their own losses in the Campaign, the French and natives attacked Deerfield.[22]

The town's palisade, constructed during King William's War, was rehabilitated and expanded.[23] In August of that year, the local militia commander called out the militia after he received intelligence of "a party of French & Indians from Canada" who were "expected every hour to make some attaque on ye towns upon Connecticut River."[24] However, nothing happened until October, when two men were taken from a pasture outside the palisade.[23] Militia were sent to guard the town in response, but these returned to their homes with the advent of winter, which was not thought to be a time for warfare.[2]

Minor raids against other communities convinced Governor Joseph Dudley to send 20 men to garrison Deerfield in February. These men, minimally trained militia from other nearby communities, had arrived by the 24th, making for somewhat cramped accommodations within the town's palisade on the night of February 28.[1][8] In addition to these men, the townspeople mustered about 70 men of fighting age; these forces were all under the command of Captain Jonathan Wells.[1]

Organizing the raid

The Connecticut River valley had been identified as a potential raiding target by authorities in New France as early as 1702.[25] The forces for the raid had begun gathering near Montreal as early as May 1703, as reported with reasonable accuracy in English intelligence reports. However, two incidents intervened that delayed execution of the raid. The first was a rumor that English warships were on the Saint Lawrence River, drawing a significant Indian force to Quebec for its defense. The second was the detachment of some troops, critically including Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville, who was to lead the raid, for operations in Maine (including a raid against Wells that raised the frontier alarms at Deerfield). Hertel de Rouville did not return to Montreal until the fall.[26]

The force assembled at Chambly, just south of Montreal, numbered about 250, and was composed of a diversity of personnel.[27] There were 48 Frenchmen, some of them Canadien militia and others recruits from the troupes de la marine, including four of Hertel de Rouville's brothers.[27][28] The French leadership included a number of men with more than 20 years experience in wilderness warfare.[27] The Indian contingent included 200 Abenaki, Iroquois, Wyandot, and Pocumtuc, some of whom sought revenge for incidents that had taken place years earlier.[27][28] These were joined by another 30 to forty Pennacook led by the sachem Wattanummon as the party moved south toward Deerfield in January and February 1704, raising the troop size to nearly 300 by the time it reached the Deerfield area in late February.[29][30]

The expedition's departure was not a very well kept secret. In January 1704, New York's Indian agent Pieter Schuyler was warned by the Iroquois of possible action. which he forwarded on to Governor Dudley and Connecticut's Governor Winthrop; further warnings came to them in mid-February, although none were specific about the target.[31]

Raid

The raiders left most of their equipment and supplies 25 to 30 miles (40 to 48 kilometers) north of the village before establishing a cold camp about 2 miles (3.2 km) from Deerfield on February 28, 1704. From this vantage point, they observed the villagers as they prepared for the night. Since the villagers had been alerted to the possibility of a raid, they all took refuge within the palisade, and a guard was posted.[32]

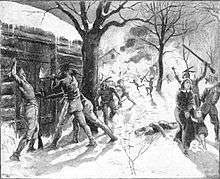

The raiders had noticed that snow drifts extended to the top of the palisade; this greatly simplified their entry into the fortifications just before dawn on February 29. They carefully approached the village, stopping periodically so that the sentry might confuse the noises they made with more natural sounds. A few men climbed over the palisade via the snow drifts and then opened the north gate to admit the rest. Primary sources vary on the degree of alertness of the village guard that night; one account claims he fell asleep, while another claims that he discharged his weapon to raise the alarm when the attack began, but that it was not heard by many people.[33] As the Reverend John Williams later recounted, "with horrid shouting and yelling", the raiders launched their attack "like a flood upon us."[33]

The raiders' attack probably did not go exactly as they had intended. In attacks on Schenectady, New York and Durham, New Hampshire in the 1690s (both of which included Hertel de Rouville's father), the raiders had simultaneously attacked all of the houses; at Deerfield, this did not happen. Historians Haefeli and Sweeney theorize that the failure to launch a coordinated assault was caused by the wide diversity within the attacking force.[34]

The raiders swept into the village, and began attacking individual houses. Reverend Williams' house was among the first to be raided; Williams' life was spared when his gunshot misfired, and he was taken prisoner. Two of his children and a servant were slain; the rest of his family and his other servant were also taken prisoner.[35] Similar scenarios occurred in many of the other houses. The residents of Benoni Stebbins' house, which was not among the ones attacked early, resisted the raiders' attacks, which lasted until well after daylight. A second house, near the northwestern corner of the palisade, was also successfully defended. The raiders moved through the village, herding their prisoners to an area just north of the town, rifling houses for items of value, and setting a number of them on fire.[36]

As the morning progressed, some of the raiders began moving north with their prisoners, but paused about a mile north of the town to wait for those who had not yet finished in the village.[37] The men in the Stebbins house kept the battle up for two hours; they were on the verge of surrendering when reinforcements arrived. Early in the raid, young John Sheldon managed to escape over the palisade and began making his way to nearby Hadley to raise the alarm. The fires from the burning houses had been spotted, and "thirty men from Hadley and Hatfield" rushed to Deerfield.[38] Their arrival prompted the remaining raiders to flee; some of them abandoned their weapons and other supplies in a panic.[37]

The sudden departure of the raiders and the arrival of reinforcements raised the spirits of the beleaguered survivors, and about 20 Deerfield men joined the Hadley men in chasing after the fleeing raiders. The English and the raiders skirmished in the meadows just north of the village, where the English reported "killing and wounding many of them".[37] However, the pursuit was conducted rashly, and the English soon ran into an ambush prepared by the raiders who had left the village earlier. Of the 50 or so men that gave chase, nine were killed and several more were wounded.[37] After the ambush they retreated back to the village, and the raiders headed north with their prisoners.[37]

As the alarm spread to the south, reinforcements continued to arrive in the village. By midnight, 80 men from Northampton and Springfield had arrived, and men from Connecticut swelled the force to 250 by the end of the next day. After debating over what action to take, they decided that the difficulties of pursuit were not worth the risks. Leaving a strong garrison in the village, most of the militia returned to their homes.[39]

The raiders destroyed 17 of the village's 41 homes, and looted many of the others. Out of the 291 people in Deerfield on the night of the attack only 126 remained in town the next day. They killed 44 residents of Deerfield: 10 men, 9 women, and 25 children, five garrison soldiers, and seven Hadley men.[3] Of those who died inside the village, 15 died of fire-related causes; most of the rest were killed by edged or blunt weapons.[40] The raid’s casualties were dictated by the raider’s goals to intimidate the village and to take valuable captives to French Canada. A large portion of the slain were infant children who were not likely to survive the ensuing trip to Canada.[41] They took 109 villagers captive; this represented forty per cent of the village population. They also took captive three Frenchmen who had been living among the villagers.[4][37] The raiders also suffered losses, although reports vary. New France's Governor-General Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil reported the expedition only lost 11 men, and 22 were wounded, including Hertel de Rouville and one of his brothers.[7][3] John Williams heard from French soldiers during his captivity that more than 40 French and Indian soldiers were lost;[3] Haefeli and Sweeney believe the lower French figures are more credible, especially when compared to casualties incurred in other raids.[7] A majority of the captives taken were women and children who French and Indian captors viewed as being more likely than adult males to successfully integrate into native communities and a new life in French Canada.[42]

Captivity and ransom

For the 109 English captives, the raid was only the beginning of their troubles.[43] The raiders intended to take them to Canada, a 300-mile (480 km) journey, in the middle of winter. Many of the captives were ill-prepared for this, and the raiders were short on provisions. The raiders consequently engaged in a common practice: they killed those captives when it was clear they were unable to keep up. Williams commented on the savage cruelty of the Indian raiders; although most killings were "not random or wanton,"[42] none of those killed would have "needed to" be killed had they not been taken in the first place. Most (though not all) of the slain were the slow and vulnerable who could not keep up with the party and would likely have died less quickly en route.[44] Only 89 of the captives survived the ordeal. Survival chances correlated with age and gender: infants and young children fared the worst, and older children and teenagers (all 21 of whom survived the ordeal) fared the best. Adult men fared better than adult women, especially pregnant women, and those with small children.[45]

In the first few days several of the captives escaped. Hertel de Rouville instructed Reverend Williams to inform the others that recaptured escapees would be tortured; there were no further escapes. (The threat was not an empty one — it was known to have happened on other raids.)[46] The French leader's troubles were not only with his captives. The Indians had some disagreements among themselves concerning the disposition of the captives, which at times threatened to come to blows. A council held on the third day resolved these disagreements sufficiently that the trek could continue.[47]

According to John Williams' account of his captivity, most of the party traveled up the frozen Connecticut River, then up the Wells River and down the Winooski River to Lake Champlain. From there they made their way to Chambly, at which point most of the force dispersed. The captives accompanied their captors to their respective villages.[48] Williams' wife Eunice, weak after having given birth just six weeks earlier, was one of the first to be killed during the trek; her body was recovered and reburied in the Deerfield cemetery.[49]

Calls went out from the governors of the northern colonies for action against the French colonies. Governor Dudley wrote that "the destruction of Quebeck [sic] and Port Royal [would] put all the Navall stores into Her Majesty's hands, and forever make an end of an Indian War",[50] the frontier between Deerfield and Wells was fortified by upwards of 2,000 men,[51] and the bounty for Indian scalps was more than doubled, from £40 to £100.[52] Dudley promptly organized a retaliatory raid against Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia). In the summer of 1704, New Englanders under the leadership of Benjamin Church raided Acadian villages at Pentagouet (present-day Castine, Maine), Passamaquoddy Bay (present-day St. Stephen, New Brunswick), Grand Pré, Pisiquid, and Beaubassin (all in present-day Nova Scotia). Church's instructions included the taking of prisoners to exchange for those taken at Deerfield, and specifically forbade him to attack the fortified capital, Port Royal.[53]

Deerfield and other communities collected funds to ransom the captives. French authorities and colonists also worked to extricate the captives from their Indian captors. Within a year's time, most of the captives were in French hands, a product of frontier commerce in humans that was fairly common at the time on both sides.[54] The French and converted Indians worked to convert their captives to Roman Catholicism, with modest success.[55] While adult captives proved fairly resistant to proselytizing, children were more receptive or likely to accept conversion under duress.[56]

Some of the younger captives, however, were not ransomed, as they were adopted into the tribes. Such was the case with Williams' daughter Eunice, who was eight years old when captured. She became thoroughly assimilated in her Mohawk family, and married a Mohawk man when she was 16. She did not see her family of origin again until much later and always returned to Kahnawake. Other captives also remained by choice in Canadian and Native communities such as Kahnawake for the rest of their lives.[57][58]

Negotiations for the release and exchange of captives began in late 1704, and continued until late 1706. They became entangled in unrelated issues (like the English capture of French privateer Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste), and larger concerns, including the possibility of a wider-ranging treaty of neutrality between the French and English colonies.[59] Mediated in part by Deerfield residents John Sheldon and John Wells, some captives (including Noel Doiron) were returned to Boston in August 1706.[60] Governor Dudley, who needed the successful return of the captives for political reason, then released the French captives, including Baptiste; the remaining captives who chose to return were back in Boston by November 1706.[61]

Many of the younger captives were adopted into the Indian tribes or French Canadian society. Thirty six Deerfield captives, mostly children and teenagers at the time of the raid, remained permanently. Those who stayed were not compelled by force, but rather by newly formed religious ties and family bonds.[62] Captive experience was largely dictated by gender as well as age. Young women most easily and readily assimilated into Indian and French Canadian societies. Nine girls remained as opposed to only five boys. These choices reflect the larger frontier pattern of incorporation of young women into Indian and Canadian society. These young women remained, not because of compulsion, fascination with the outdoor adventure, or the strangeness of life in a foreign society, but because they transitioned into established lives in new communities and formed bonds of family, religion, and language.[63] In fact, more than half of young female captives who remained settled in Montreal where "the lives of these former Deerfield residents differed very little in their broad outlines from their former neighbors." Whether in New France or in Deerfield these women generally were part of frontier agricultural communities where they tended to marry in their early twenties and have six or seven children.[64] Other female captives remained in Native communities such as Kahnawake. These women remained because of bonds of religion and family. While European males castigated the "slavery" of Indian women, captive women from this time commonly chose to remain in Native society rather than return to colonial English settlements.[65]

John Williams wrote a captivity narrative, The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion, about his experience, which was published in 1707. Williams' narrative was published during ongoing ransom negotiations and pressed for greater activity to return the Deerfield captives. Written with assistance from prominent Boston Puritan minister Reverend Cotton Mather, the book framed the raid, captivity, and border relations with the French and Indians in terms of providential history and God’s purpose for Puritans.[66] The work was widely distributed in the 18th and 19th centuries, and continues to be published today (see Further Reading below). Williams' work was one of the reasons this raid, unlike similar others of the time, was remembered and became an element in the American frontier story.[67] Williams' work transformed the captivity narrative into a celebration of individual heroism and the triumph of Protestant values against savage and "Popish" enemies.[68]

Legacy and historical memory

Deerfield holds a "special place in American history."[69] As Mary Rowlandson's popular captivity narrative The Sovereignty and Goodness of God did a generation earlier, the sensational tale stressed reliance on God's mercy and "kept alive the spirit of the Puritan mission" in eighteenth century New England.[70] Williams' account heightened tensions between English settlers and Native Americans and their French allies and led to more war preparedness among settler communities.[71]

The events at Deerfield were not commonly described as a massacre until the 19th century. Reverend John Taylor's 1804 centennial memorial sermon first termed the events at Deerfield a "massacre." Previous eighteenth-century accounts emphasized the physical destruction and described the raid as "the assault on," "the destruction of," or "mischief at" Deerfield.[72] Viewing the raid as a "massacre," 19th century New Englanders began to remember the attack as part of the larger narrative and celebration of American frontier spirit. Persisting into the twentieth century, American historical memory has tended to view Deerfield in line with Frederick Turner's Frontier Thesis as a singular Indian attack against a community of individualistic frontiersmen.[73] Re-popularized and exposed to a national audience in the mid-twentieth century with the establishment of Historic Deerfield, the raid was contextualized in a celebration of exceptional American individual ambition. This view has served as a partial justification for the removal of Native Americans and has obscured both the larger patterns of border conflict and tensions and the family based structure of Deerfield and similar marginal settlements.[74] Although popularly remembered as a tale of the triumph of rugged Protestant male individualism, the raid is better understood not along the lines of Turner's thesis, but as an account of the strong factors of community life and cross-cultural interaction in border communities.[75]

An 1875 legend recounts the attack as an attempt by the French to regain a bell, supposedly destined for Quebec, but pirated and sold to Deerfield. The legend continues that this was a "historical fact known to almost all school children."[76] However, the story, which is a common Kahnawake tale, was refuted as early as 1882 and does not appear to have significantly affected American perception of the raid.[77]

Canadians and native Americans who are less influenced by Williams' narrative and Turner's thesis, have given the raid a more ambivalent place in memory. Canadians view the raid not as a massacre and mass abduction but as a successful local application of guerilla techniques in the broader context of international war and stress the successful integration of hundreds of captives taken in similar conflicts during Queen Anne's War.[78] Similarly, most Native American records justify the action in a larger military and cultural context and remain largely unconcerned with the particular event.[79]

A portion of the original village of Deerfield has been preserved as a living history museum, Historic Deerfield; among its relics is a door bearing tomahawk marks from the 1704 raid.[74][80] The raid is commemorated there on the weekend closest to February 29. Moving towards a more inclusive Historic Deerfield's yearly reenactment and educational programs treat "massacre" as a "dirty word" and stress Deerfield as a place to study cultural interaction and difference at society's borders.[76]

In addition, The Ransom of Mercy Carter by Caroline B. Cooney, a historical fiction novel, commemorates this event through the eyes of a young Deerfield girl.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 98

- 1 2 Melvoin, p. 215

- 1 2 3 4 Melvoin, p. 221

- 1 2 Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 115

- ↑ Melvoin, Richard (1989). New England Outpost:War and Society in Colonial Deerfield. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 456.

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 125

- 1 2 3 Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 123

- 1 2 Melvoin, pp. 215–216

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 273–274

- ↑ Melvoin, pp. 26–29

- ↑ Melvoin, pp. 39–47

- ↑ Melvoin, pp. 52–58

- ↑ Borneman, Walter R (2006). The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Melvoin. p. 483. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 20

- ↑ Drake, James David (1999). King Philip's War: Civil War in New England, 1675-1676. The University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 1558492240.

- ↑ Melvoin, pp. 108,114

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 21

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 115

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 121

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 29–30

- ↑ New York Colonial Documents. Vol. IX, p. 762

- 1 2 Melvoin, p. 213

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 212

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 38

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 99

- 1 2 3 4 Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 100

- 1 2 Calloway, p. 31

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 111

- ↑ Calloway, p. 47

- ↑ Haefeli andn Sweeney, pp. 110–111

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 216

- 1 2 Melvoin, p. 217

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 113

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 218

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 115–119

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Melvoin, p. 220

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 219

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 121–122

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 122

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 122. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Melvoin. p. 481. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 5 and 150. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 130. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Demos, John (1994). The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. New York: Knopf. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-394-55782-3. OCLC 237118051.

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 127

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 130–135

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 129

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 128

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 191

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 190

- ↑ Melvoin, p. 229

- ↑ Clark, p. 220

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 147

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, pp. 157–163

- ↑ Melvoin. pp. 484–486. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Attack on Deerfield (paragraph #2)". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- ↑ Christopher Gist Journal one ex-Deerfield captive Mary Harris was living at Kahnawake in 1756

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 165

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 173

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 174

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 157 and 207. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 222–223. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 242. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Demos. p. 164. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 177. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney, p. 273

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 178–179. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Dufour, Roland P (1994). Colonial America. Minneapolis/St. Paul: West Publishing Company. p. 437.

- ↑ Melvoin. p. 508. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 272–274. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 18. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Haefeli and Sweeney. pp. 273–274. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Melvoin. p. 598. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 272. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Child. p. 23. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Eccles, W.J. (1998). The French in North America, 1500–1783. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Haefeli and Sweeney. p. 274. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Johnson and Smith. p. 44. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

References

- Calloway, Colin Gordon (1997). After King Philip's War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-0-87451-819-1. OCLC 260111112.

- Child, Hamilton (1883). Gazetteer and Business Directory of Lamoille and Orleans Counties, Vermont. Syracuse, NY. OCLC 7019124.

- Clark, Andrew Hill (1968). Acadia, the Geography of Early Nova Scotia to 1760. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. OCLC 186629318.

- Haefeli, Evan; Sweeney, Kevin (2003). Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-503-6. OCLC 493973598.

- Johnson, Michael; Smith, Jonathan (2006). Indian Tribes of the New England Frontier. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-937-0. OCLC 255490222.

- Melvoin, Richard (1989). New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02600-9. OCLC 17260551.

Further reading

- Smith, Mary (1991) [1976]. Boy Captive of Old Deerfield. Deerfield, MA: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association. ISBN 978-0-9612876-5-8. OCLC 35792763.

- Williams, John (1833). Leavitt, Joshua, ed. The Redeemed Captive: a Narrative of the Captivity, Sufferings, and Return of the Rev. John Williams, Minister of Deerfield, Massachusetts, who was taken Prisoner by the Indians on the Destruction of the Town, A.D. 1704. New York: S. W. Benedict. OCLC 35735291. A 19th-century printing of Williams' narrative

- Williams, John; West, Stephen; Taylor, John (1969). The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion: or, The Captivity and Deliverance of Rev. John Williams of Deerfield. New York: Kraus. OCLC 2643638. 1969 reprint of a 1908 edition of Williams' narrative

- Fournier, Marcel (1992). De la Nouvelle Angleterre à la Nouvelle France - L'histoire des captifs anglo-américains au Canada entre 1675 et 1760. Montréal, Canada: Société Généalogique Canadienne-Française. ISBN 2-920761-31-5. A study of the story of Anglo-Canadian captives who were taken by French Canadians and Abenaki Indians to Nouvelle France's Québec, where some of whom settled.

External links

- Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704, An interactive website about the raid's origins, participants, and consequences, Deerfield Museum

- Digital Collection "Old Indian House" (photo) and (painting)

- Frary House

- "Historic Deerfield Buys 1703 letter that predicts attack"

- Fates of Individuals Taken Captive at Deerfield, Babcock

Coordinates: 42°32′55″N 72°36′26″W / 42.548569°N 72.607105°W