2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire

The 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire (Persian: جشنهای ۲۵۰۰ سالهٔ شاهنشاهی ایران), officially known as The 2,500th year of Foundation of Imperial State of Iran (Persian: دوهزار و پانصدمین سال بنیانگذاری شاهنشاهی ایران ), consisted of an elaborate set of festivities that took place on 12–16 October 1971 on the occasion of the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Imperial State of Iran and Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great. The intent of the celebration was to demonstrate Iran's old civilization and history to showcase its contemporary advancements under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran.

Planning

.jpg)

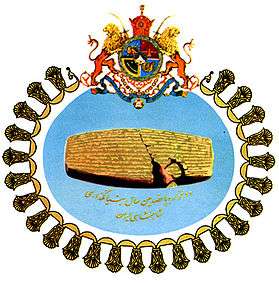

The planning for the party took a year, according to the BBC Storyville documentary Decadence and Downfall: The Shah of Iran's Ultimate Party, which interviewed the people tasked by the Shah to organize the party. The Cyrus Cylinder served in the official logo as the symbol for the event. With the decision to hold the main event at the ancient city Persepolis near Shiraz, the local infrastructure had to be improved including the Shiraz airport and a highway to Persepolis. While the press and supporting staff would be housed in Shiraz, the main festivities were planned for Persepolis that for this occasion would be the site of an elaborate tent city. The area around Persepolis was cleared of snakes and other vermins.[1] Other events were scheduled for Pasargadae, the site of the tomb of Cyrus the Great, as well as Tehran.

Tent City of Persepolis

The Tent City (also Golden City) was planned by the Parisian interior-design firm of Maison Jansen on 160 acres (0.65 km2) and took its inspiration from the meeting between Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.[1] Fifty 'tents' (actually prefabricated luxury apartments with traditional Persian tent-cloth surrounds) were arranged in a star pattern around a central fountain, and vast numbers of trees were planted around them in the desert, recreating something of how the ancient Persepolis would have looked. Each tent had direct telephone and telex connections back to its respective country and the whole celebration was televised to the world by way of a satellite connection from the site.

The large Tent of Honor was designed for the reception of the dignitaries. The Banqueting Hall was the largest structure and measured 68 by 24 meters. The tent site was surrounded by gardens of trees and other plants flown in from France and adjacent to the ruins of Persepolis. Catering services were provided by Maxim's de Paris, which closed its restaurant in Paris for almost two weeks to provide for the glittering celebrations. Legendary hotelier Max Blouet came out of retirement to supervise the banquet. Lanvin designed the uniforms of the Imperial Household. 250 red Mercedes-Benz limousines were used to chauffeur guests from the airport and back. Dinnerware was created by Limoges and linen by Porthault.

Festivities

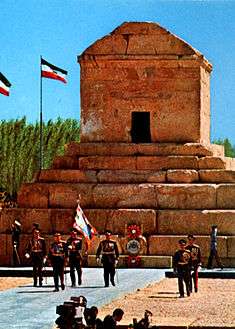

The festivities were opened on 12 October 1971, when the Shah and the Shahbanu paid homage to Cyrus the Great at his mausoleum at Pasargadae. For the next two days, the Shah and his wife greeted arriving guests, often directly at the Shiraz airport. On 14 October, a grand gala dinner took place in the Banqueting Hall in celebration of the birthday of the Shahbanu. Sixty members of royal families and heads of state were assembled at the single large serpentine table in the Banqueting Hall. The official toast was raised with a Dom Perignon Rosé 1959.

The food and the wine for the celebration were provided by the Parisian restaurant Maxim's.[2] The banquet menu was:

- Quails' eggs stuffed with golden, Imperial Caspian caviar (the Shah had artichokes as he was allergic to caviar), Champagne and Château de Saran

- Mousse of crayfish tails with Nantua sauce, Château Haut-Brion Blanc 1964

- roast saddle of lamb with truffles, Château Lafite Rothschild 1945

- Champagne sorbet, Moët et Chandon 1911

- 50 roast peacocks—Iran's ancient national symbol—with restored tail feathers, stuffed with foie gras, accompanied by roast quails and a nut and truffle salad Musigny Comte Georges de Vogüé 1945

- Glazed oporto ring of fresh figs with cream, raspberry champagne sherbet and port, Dom Perignon Rosé 1959 reserve vintage

- mocha coffee

- cognac Prince Eugène

Six hundred guests dined over five and a half hours thus making for the longest and most lavish official banquet in modern history as recorded in successive editions of the Guinness Book of World Records. A son et lumière show, the Polytope of Persepolis designed by Iannis Xenakis and accompanied by the specially-commissioned electronic music piece Persepolis[3] concluded the evening. The next day saw a parade of armies of different Iranian empires covering two and half millennia by 1,724 men of the Iranian armed forces, all in period costume. In the evening, a less formal "traditional Persian party" was held in the Banqueting Hall as the concluding event at Persepolis.[4]

On the final day, the Shah inaugurated the Shahyad Tower (later renamed the Azadi Tower after the Iranian revolution) in Tehran to commemorate the event. The tower was also home to the Museum of Persian History. In it was displayed the Cyrus Cylinder, which the Shah promoted as "the first human rights charter in history".[5][6] The cylinder was also the official symbol of the celebrations, and the Shah's first speech at Cyrus' tomb praised the freedom that it had proclaimed, two and a half millennia previously. The festivities were concluded with the Shah paying homage to his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi, at his mausoleum.[4]

The event brought together the rulers of two of the oldest extant monarchies, the Shah and Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia. By the end of the decade, both monarchies had ceased to exist.

Security

Security was a major concern. Persepolis was a favoured site for the festivities as it was isolated and thus could be tightly guarded, a very important consideration when many of the world's leaders were gathered there. Iran's security services, SAVAK, captured and took into "preventive custody" anyone that it suspected to be a potential "troublemaker".[1]

Criticism

Criticism was voiced in the western press and by Muslim clerics such as Khomeini and his followers; Khomeini called it the "Devil's Festival".[1] The Ministry of the Court placed the cost at $17 million; Ansari, one of the organizers, puts it at $22 million.[1] The actual figure is difficult to calculate exactly and is a partisan issue, but may have exceeded $200 million. The defenders of the activities point out benefits such as the opening of museums, improvements in infrastructure and its positive effect on Iran's international public relations.

List of guests

Elizabeth II had been advised not to attend, with security being an issue.[1] Prince Philip and Princess Anne represented her instead.[7] Other major leaders who did not attend were Richard Nixon and Georges Pompidou. Nixon had initially planned to attend but later changed his mind and sent Spiro Agnew instead.[1]

Some of the guests who were invited include:

Royals and viceroys

Presidents and Prime Ministers

Film

Iran's National Film Board produced a documentary of the celebrations, titled Forugh-e Javidan (Persian: فروغ جاویدان) in Persian and Flames of Persia in English. Farrokh Golestan directed, and Orson Welles agreed to narrate the English text, written by Macdonald Hastings, in return for the shah's brother-in-law funding his own film, The Other Side of the Wind.[8][9] The film was aimed at a western audience.[10] Despite a requirement to show the film in 60 cinemas in Tehran, its "overheated rhetoric" and popular resentment at the extravagance of the event meant it did poorly at the domestic box office.[11]

Today

Persepolis remains a major tourist attraction in Iran and apparently there are suggestions to rehabilitate the archeological site as it is a proclamation of Iranian history.[7] In 2005, it was visited by nearly 35,000 people during the Iranian new year holiday.[7]

The tent city remained operating until 1979 for private and government rent, when it was looted after the departure of Shah. The iron rods for the tents and roads for the festival area still remain and are open as a park, but there are no markers making any reference to what they were for.[12] The rededicated Azadi Tower remains as a major landmark in Tehran.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kadivar C (25 January 2002). "We are awake. 2,500-year celebrations revisited". Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ↑ Van Kemenade, Willem (November 2009). "Iran's relations with China and the West" (PDF). Clingendael. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Karkowski, Z.; Harley, J.; Szymanksi, F.; Gable, B. (2002). "Liner Notes". Iannis Xenakis: Persepolis + Remixes. San Francisco: Asphodel LTD.

- 1 2 "The Persepolis Celebrations". Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ↑ British Museum explanatory notes, "Cyrus Cylinder": "For almost 100 years the cylinder was regarded as ancient Mesopotamian propaganda. This changed in 1971 when the Shah of Iran used it as a central image in his own propaganda celebrating 2500 years of Iranian monarchy. In Iran, the cylinder has appeared on coins, banknotes and stamps. Despite being a Babylonian document it has become part of Iran's cultural identity."

- ↑ Neil MacGregor, "The whole world in our hands", in Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice, p. 383–4, ed. Barbara T. Hoffman. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-85764-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tait, Robert (22 September 2005). "Iran to rebuild spectacular tent city at Persepolis". The Guardian. Persepolis. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Naficy, Hamid (2003-12-16). "Iranian Cinema". In Oliver Leaman. Companion Encyclopedia of Middle Eastern and North African Film. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781134662524. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Welles, Orson (1998). This is Orson Welles. Perseus Books Group. p. xxvii. ISBN 9780306808340.

- ↑ Watson, James A.F. (March 2015). "Stop, look, and listen: orientalism, modernity, and the Shah's quest for the West's imagination" (PDF). The UBC journal of Political Studies. Vancouver: Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia. 17: 22–36: 26–28.

- ↑ Naficy, Hamid (2011-09-16). A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978. Duke University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780822347743. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Iran Daily (23 June 2007). "Team Named For Renovating Persepolis". Retrieved 9 March 2008.

External links

- 1971 Celebration of the Shah of Persia in Persepolis (ARTE Documentary Film)

- 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire on Facebook

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2500 year celebration of the Persian Empire. |