3rd Portuguese India Armada (Nova, 1501)

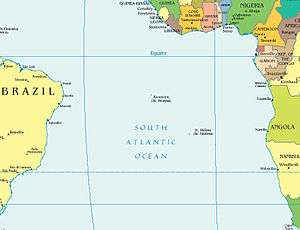

The Third India Armada was assembled in 1501 on the order of King Manuel I of Portugal and placed under the command of João da Nova. Nova's armada was relatively small and primarily commercial in objective. Nonetheless, they engaged the first significant Portuguese naval battle in the Indian Ocean. The Third Armada is also credited for the first discovery of the uninhabited islands of Ascension and Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. There is also some speculation that it may have been the first Portuguese armada to reach Ceylon.

The fleet

Of all the early Portuguese India armadas, the Third Armada of 1501 is perhaps the most elusive. The chroniclers' accounts are scant on details and differ significantly at several points. There are very few contemporary documents to help us substantiate information, reconcile accounts or supply missing details.

The Third Armada was primarily a commercial run to India, composed of only four ships, two owned by the crown, two privately owned, plus (possibly) one supply ship.

| Ship Name | Captain | Notes |

| 1. uncertain | João da Nova | Flagship. Owned by crown. |

| 2. uncertain | Francisco de Novais | Owned by crown. |

| 3. uncertain | Diogo Barbosa | Privately owned by D. Álvaro of Braganza, partially outfitted by Marchionni consortium |

| 4. uncertain | Fernão Vinet | Florentine. Private, owned by Marchionni consortium partner Girolamo Sernigi may have been aboard as factor.[1] |

| 5. supply ship? | unknown | Uncertain if existed. If it did, then probably scuttled and burnt along the way. |

This list of captains is given in João de Barros's Décadas,[2] Damião de Góis's Chronica,[3] Castanheda's História,[4] Couto's list,[5] Faria e Sousa's Asia [6] and Quintella's Annaes.[7] Barbosa is replaced by a certain "Fernão Pacheco" in the lists given by Gaspar Correia's Lendas[8] and the Relação das Naus.[9] The Livro de Lisuarte de Abreu replaces Novais and Barbosa with Rui de Abreu and Duarte Pacheco (!).[10])

This modest armada carried 350-400 men, only 80 of which were armed.[11] The admiral was João da Nova, a Galician-born minor noble, alcaide pequeno of Lisbon, whose principal recommendation was probably his connection to the powerful Portuguese nobleman Tristão da Cunha.[12]

.jpg)

The owners of the two private ships, D. Álvaro of Braganza and the Florentine Bartolomeo Marchionni, happened to have jointly outfitted the Anunciada, one of the ships of the Second India Armada of Pedro Álvares Cabral that was still out at sea at the time. It was a considerable gamble for these private entities to outfit new ships before knowing the results of their previous enterprise. As it happens, the Anunciada would return safely to Lisbon later that same year, with a splendid cargo of spices.

One of the passengers on the fleet was Paio Rodrigues, an employee of D. Álvaro of Braganza, who was under instructions to remain as a factor in India, not for the crown but for the private consortium. Another was Álvaro de Braga, a crown factor designated for Sofala.

The mission

The objective of the Third Armada was wholly commercial. Their mission was to go to India, load up with spices, and return home. It was expected to be uneventful.

Their destination was Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode), the principal spice entrepôt in Kerala and dominant city-state on the Malabar coast of India. The Third Armada expected - or hoped - that the well-equipped Second India Armada of Pedro Álvares Cabral, that had departed the previous year (1500), had succeeded in its ambassadorial mission to secure a treaty with Calicut and set up a factory (feitoria) there. What they could not have guessed before their departure, of course, was that Cabral's Second Armada had not only failed in that mission, they had opened hostilities between Portugal and Calicut. João da Nova's little Third Armada was sailing into a war it did not expect and was not equipped for.

The Third Armada seems to also have expected to put in at Sofala, where Cabral had also been instructed to set up a factory. According to Correia, the crown ship of Francisco de Novais was designated to go to trade for gold in Sofala and drop off the factor Álvaro de Braga, the clerk Diogo Barbosa (same name as captain) and an additional twenty-two men.[13] In any case, Cabral's Second Armada had fumbled that mission too - there was no Portuguese factory in Sofala.

Unfortunately, the Third Armada could not have delayed its departure until the arrival of the news of the Second Armada. The seasonal monsoon wind patterns of the Indian Ocean imposed the requirement that India-bound expeditions must leave Lisbon by April at the latest, if they were to have any hope of catching the summer southeasterly winds from Africa to India. Unfortunately, those same wind patterns determined that return fleets would only arrive in Europe in the summer, June at the earliest. Although the difference between one fleet's departure and another fleet's arrival was only a matter of a couple of months, outbound fleets could not delay their departure until the previous year's fleet returned, or else an entire year would be lost.

It is for this reason that both the crown and the private consortium's were willing to equip and launch the Third Armada in March, 1501 before they had received any news of the outcome of the Second Armada, the earliest ship of which only arrived in late June.

Nova's Third Armada would learn of the turn of events along the way from notes and letters left by Cabral's ships at African staging posts. But there was no question of returning home to pick up reinforcements. The lightly armed Third Armada would have to press on, sneak into India stealthily, avoid Calicut, load up at the friendly ports, and slip away as quickly as possible.

The outward voyage

March 5, 1501 - The Third Armada of João da Nova, composed of four ships (possibly five, if accompanied by a supply ship) sets out from Lisbon. (alternative date of April 10 has also been suggested.[14]

May, 1501 - According to Correia (but not the other chroniclers), following the instructions given by Gaspar de Lemos/André Gonçalves (the captain of the ship that had returned from Brazil the previous year) João da Nova's expedition strikes southwest and makes a brief watering stop at Cape St. Augustine (northeast Brazil), before heading on towards southern Africa.[15]

May 1501 - Discovery of Ascension Island (?) According to chroniclers Barros and Gois (but not Correia), proceeding in the South Atlantic, João da Nova sighted the south Atlantic Ascension Island which he names Ilha da Conceição ("Conception Island", it was only named ilha da Ascensção in 1503, when it was re-discovered by Afonso de Albuquerque. However, see discussion below.)

July 7, 1501 - After crossing the Cape of Good Hope without known incident, João da Nova's fleet anchors at Mossel Bay (Aguada de São Brás). There, in a shoe by the watering hole, Nova finds the note left a month or so earlier by Pêro de Ataíde, one of the captains of the returning Second Armada.[16] Ataíde's note warns all captains bound for India that Calicut is now hostile to the Portuguese, but that Cochin and Cannanore are friendly ports where spices may be procured. They are also informed that captains bound for India should go by way of Malindi where they will find letters from Pedro Álvares Cabral held by a Portuguese degradado, which contain more detailed information.[17] (The milkwood tree where Ataíde hung his shoe was declared a national monument in South Africa, and a shoe-shaped postbox erected below it).[18]

mid-July, 1501 - The Third Armada arrives at Mozambique Island. Discarding his instructions, Nova decides against dispatching Novais's ship to Sofala. Contemplating the new hostile state of affairs in India, Nova probably concluded he decided that he needs to take all the men he had in case of a military engagement in India.[19] He sets sail up the East African coast soon after. It is possibly now that Nova discovers what has since been called Juan de Nova Island [20] in the Mozambique Channel and possibly also the Farquhar atoll (part of the Seychelles, were also named 'João da Nova islands' until the 19th century.[21])

mid-July, 1501 - Climbing up the coast, the Third Armada arrives at the Swahili citadel of Kilwa (Quiloa). They are greeted on the beach (or on a rowboat) by a Portuguese degredado (António Fernandes, carrying Cabral's letters, according to Barros and Gois; Pero Esteves, with no letters, according to Correia)[22] Fernandes/Esteves informs Nova of the state of affairs in Kilwa. Barros suggests that, on this occasion, João da Nova might have personally met Muhammad Arcone, a Kilwan noble who would later play a critical role in Portuguese-Kilwan affairs. But Correia notes Nova was wary of approaching Kilwa, and refused to go ashore, despite repeated invitations; he had the degredado negotiate the provision of some supplies (probably citrus fruit) from the city for his scurvy-sick crews, and hurriedly moved on.

Late July 1501 - Barros suggests that after leaving Kilwa, the Third Armada immediately set sail for India. But Correia claims Nova sailed first to Malindi, to deliver a letter from King Manuel I of Portugal to the Sultan of Malindi.[23] The sultan of Malindi receives the Portuguese well, supplying them amply with biscuit, rice, butter, chickens, sheep and other foodstuffs. Correia claims that it is now that Nova picks up the letters that Cabral had dispatched by messenger from Mozambique, and learns more of the details of the falling out with the Zamorin of Calicut, the Portuguese factory at Cochin and the friendly relations with Cannanore and Quilon.[24]

July 28, 1501 - The Third Armada leaves Malindi and sets across its Indian Ocean crossing. Catching the favorable monsoon winds, the journey will take eighteen days (according to Correia.)[25]

Nova in India

.gif)

August, 1501 - João da Nova's Third Armada alights in India, at Santa Maria islands off the Malabar coast (according to Correia, so named at this time because of the feast of the Assumption of Mary (August 15).[26]

What ensues varies in the chronicles. Barros suggest he immediately began making his way down the Indian coast towards Kerala, but Correia suggests he stopped by the port of Batecala (Bhatkhal), then the principal trade port of the Vijayanagara Empire and lingered there, engaging in some trade with a variety of merchants in the harbors, and chasing down some pirates in Onor (Honnavar).[27] The Third Armada eventually begins making its way down the Indian coast towards Kerala, capturing two merchant ships (allegedly from Calicut) near Mount d'Eli along the way.[28]

The two-month delay between the Third Armada's reputed arrival in India (August) and their first recorded activities in India (November) is unusual and been subject to some speculation.[29] As suggested by Correia, the Third Armada seems to have simply lingered in the area between Batecala and Mount d'Eli,to do some trading and maybe some piracy too, before heading south to Cannanore.

On the other hand, it has been hypothesized that during this interlude, Nova might have launched some exploratory ventures in the area during, in particular taken a wide swing far south, below Cape Comorin, to see if he could locate the fabled island of 'Taprobana' (Ceylon), the world's main source of cinnamon (see below.)

c.November, 1501 - The Third Armada arrives in Cannanore (Cananor, Kannur). They are well received by the Kolathiri Raja of Cannanore, who immediately urges João da Nova to load up his ships with spices from that city's markets. Nova side-steps the offer courteously, noting that he must first collect the supplies already acquired by the Portuguese factory in Cochin (Cochim, Kochi). Nonetheless, before setting off, Nova drops off a few agents, with instructions to initiate arrangements to purchase spices (principally ginger and cinnamon) in the Cannanore markets, to be picked up later.

It is sometimes said that Nova established the Portuguese factory in Cannanore at this point. However, the factor he left behind was Paio Rodrigues, is a private agent of D. Álvaro of Braganza and the Marchionni consortium, not an employee of the Casa da India (the crown trading house). The Casa (and thus the Portuguese Crown) will only install a factor in Cannanore on the next expedition (4th Armada).

While in Cannanore, João da Nova receives an embassy from the Zamorin of Calicut. Accompanying them is Gonçalo Peixoto, a Portuguese survivor of the previous year's massacre, who had remained stuck in Calicut for the past year. In his letter, the Zamorin expresses his sadness at the Calicut Massacre of December 1500, blaming it on old hatreds between Muslims and Christians which he never understood, that he, a Hindu prince, had only a desire for friendship and peace with Portugal. He reports that the ringleaders of the riot had already been rounded up and punished, and invites Nova to Calicut to collect the wares left behind in the Portuguese factory and receive compensation. He also proposes to dispatch a pair of his own ambassadors with Nova's fleet back to Lisbon, to make a final treaty with King Manuel I of Portugal.[30] The Kolathiri Raja of Cannanore is impressed, and recommends that Nova take up the offer. However, Gonçalo Peixoto warns Nova not to believe a word of it, that the Zamorin is luring him into a trap, and is currently preparing a war fleet in Calicut. Nova decides not to reply to the Zamorin's entreaty. Peixoto, seeing no reason to return to Calicut, joins Nova's fleet.

Correia reports this event differently. He asserts that Peixoto had not come and that Nova had taken up the offer from the Zamorin's emissary to Cannanore and sailed to Calicut. The Third Armada anchors by the harbor there, waiting for the promised wares to be shipped from shore, when an unnamed Christian comes aboard and warns him about the Zamorin's intentions.[31] Nova decides to leave, but not without a show of force first. He pounces on three merchant ships, including one owned by the Zamorin himself, at the mouth of Calicut harbor, seizing their cargoes and burning the vessels in plain view of the city. Some valuable silver Indian nautical instruments and navigational charts are among the loot seized from these ships.

Arriving in Cochin, João da Nova encounters the factor left behind by Cabral, Gonçalo Gil Barbosa. Barbosa reports trading difficulties in the local markets. Indian spice merchants require payment in cash (silver principally), but Cabral had left him only with a stock of Portuguese goods (cloth mainly), expecting him to use the revenues from their sale to buy up the spices. But European goods have little vent in Indian markets, and Barbosa is still saddled with his unsold stock, unable to raise the cash to buy the spices. Barbosa seems to suspect that the Arab merchant guilds have engineered a boycott of Portuguese goods on Indian markets. He also reports that the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin, despite his alliance and protection of the factory, is in fact furious at the Portuguese because Cabral's Second Armada had departed so suddenly (without cordialities and taking two noble Cochinese noble hostages with them).

The lack of silver cash seems to be the pressing problem that Nova did not anticipate. He certainly did not bring much cash with him, having also expected to sell Portuguese goods in India to raise it.[32]

Nova immediately sets sail back to Cannanore, to see if the agents he left there had any more success, but they are facing much the same problem - Portuguese merchandise is going unsold, and the spice merchants are demanding payment in silver. The Third Armada's mission is on the verge of failure, when the Kolathiri Raja of Cannanore intervenes, and places himself as security for the sale of spices to the Portuguese on credit. This breaks the deadlock and allows the Portuguese to finally load up on the spice markets.

Discovery of Ceylon?

In 1898, excavations underneath the Breakwater Office in Colombo, Sri Lanka, revealed a boulder with a Portuguese inscription, a coat of arms, alongside the clearly denoted date 1501 (see Report, 1899) - that is, four years before Lourenço de Almeida's arrival on the island, the formal date (1505) of the Portuguese discovery of Ceylon. Much speculation has surrounded this mysterious inscription. At first, it was speculated to have been an uncompleted gravestone for a Portuguese captain born in 1501 (death date missing), but the arms and style of the inscription has all the trappings of a Portuguese padrão, the typical marker of a Portuguese claim. Some argue the date is simply a mistake, or that the "1" in 1501 is simply some other poorly carved digit. Another possibility is that it is not a number at all, but an acronym, ISOI (Iesus Salvator Orientalium Indicorum - 'Jesus the Savior of the East Indies')

Nonetheless, some historians (notably, Bouchon, 1980) have argued that the inscription was probably made by a captain of the Third Armada of 1501. Alas, there is no written record or chronicle suggesting that the Third Armada stumbled upon Ceylon. On the other hand, the activities of the Third Armada as a whole are poorly recorded, so it is not out of the question either.

If the Third Armada did stumble upon Ceylon, when might such a jaunt have happened? The most obvious possibility is sometime during the two-month gap (already mentioned above) - that is sometime between the departure from Africa (August 1501) and arrival in Cannanore (November).

Bouchon (1980) speculates it was an exploratory venture launched from Angediva/Santa Maria. However, that would mean Nova went south along the Indian coast and doubled back north, without stopping at the Portuguese factory in Cochin on either leg. This is unlikely, as there was really nothing back in Angediva/Santa Maria to return to. Moreover, one of the captains of the Third Armada, Diogo Barbosa, happened to be the uncle of the Cochin factor Gonçalo Gil Barbosa, and would likely have been anxious to stop by as soon as possible.[33]

An alternative possibility is that Third Armada struck too far south at the crossing to begin with, missing the Indian coast entirely, and ended up at Ceylon directly (whether by accident or intention). Being forced to take a wide swing northwest to get to India, landing at Santa Maria/Angediva on their second try, might be a better explanation for the long interlude.

Finally, there is the possibility, also suggested by Bouchon (1980: p. 257) that the journey to Ceylon was later - specifically, sometime in late November/early December 1501. That is, after realizing the cash constraint problem in Cochin, Nova did not immediately return to Cannanore, but he (or one of his captains) undertook a journey to Ceylon, probably guided by a local pilot, hoping that the Portuguese merchandise would have better success there.

Nonetheless, none of this is confirmed or suggested in any written accounts. The mysterious inscription on the boulder in Colombo is really all there is to go on.[34]

Naval Battle of Cannanore

Mid-December 1501 – Having loaded up with the spices they could get on credit in Cannanore (plus whatever cargoes they managed to steal by piratical attacks on Malabari ships), João da Nova prepares the Third Armada to leave India. However, news soon arrives that the battle fleet of the Zamorin of Calicut is bearing down on Cannanore.

December 31, 1501[35] - As he is about to set out of Cannanore, João da Nova's Third Armada is cornered in the bay by a fleet dispatched by the Zamorin of Calicut, composed of nearly forty large ships, plus some 180 small paraus and zambuks, an estimated armed Malabari force of 7,000 men.[36]

The Raja of Cannanore urges João da Nova to stay under his protection and avoid a fight. But Nova, noticing the landside breeze in his favor, decides to attempt a break-out. After a few rounds of cannon open a little hole in the Calicut line, Nova orders his four ships into a column formation and charges through it, cannon blasting on either side. The powerful Portuguese cannonades and carracks' height foil Malibari attempts to throw grappling hooks and board the Portuguese quartet. As the Portuguese column continues out to sea, Nova continues firing his cannon relentlessly at his pursuers. The Calicut fleet, less seaworthy, begins to splinter and lag behind. As the Third Armada pulls away, the prospect of a grapple dims, and the battle is limited to a ranged artillery duel. The Malabari ships quickly realize their Indian cannon cannot match the range and speed of reloading of the Portuguese cannon, and begin to turn away. At this point, Nova gives a brief chase, before finally breaking up the engagement on January 2, 1502.

On the whole, after two days of fighting, the Third Armada had sunk five large ships and about a dozen oar-driven boats. But they inflicted a great deal of damage on the remaining Malabari vessels, while sustaining very little damage themselves.

Although João da Nova had not come prepared for a fight, the two-day naval battle off Cannanore was the perhaps the first significant Portuguese naval engagement in the Indian Ocean. It was not the first clash between Portuguese and Indian ships - Gama's First Armada and Cabral's Second Armada had their share. But earlier encounters had been largely with poorly armed merchant ships, scrawny pirates and isolated squads, targets a single, well-armed fighting caravel could see off without much difficulty. This time, the Zamorin of Calicut had attacked directly, stretching his sinews to deploy the best his navy could offer against a small group of relatively lightly armed Portuguese merchant carracks. The results were disheartening to the Malabari sea-king.

The Battle of Cannanore made abundantly clear the great disparity between European and Indian technology in ship design and artillery - a gap that, in subsequent years, the Portuguese would repeatedly exploit and the Zamorin of Calicut was desperate to close. To nullify the Portuguese naval superiority, the Zamorin would have to stick to land or look abroad - to the Arabs, the Turks and Venetians.

The battle is also historically notable for being one of the earliest recorded deliberate uses of a naval column, later called line of battle, and for resolving the battle by cannon alone. These tactics would become increasingly prevalent as navies evolved and began to see ships less as carriers of armed men, and more as floating artillery. In that respect, this has been called the first 'modern' naval battle (at least for one side).[37]

Return voyage

Early 1502 - Before finally undertaking his ocean crossing, the Third Armada captured one last ship, a Calicut merchant ship off Mount d'Eli, which after sacking, they burnt and sunk. On the return journey, the Third Armada made two watering stops in East Africa - first at Malindi (where he dropped off some letters, that would be picked up later that year by Thomé Lopes), the second at Mozambique Island.[38]

May 3, 1502 (long thought to be May 21) Discovery of St. Helena - After turning the Cape of Good Hope, João da Nova sails into the south Atlantic Ocean and discovers the uninhabited island of Saint Helena along the way.[39] It is believed to be named after saintly empress. By tradition this was the feast-day of Saint Helena on 21 May, but this date has been shown in a 2015 paper to have been originated by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten who mistakenly quoted the Protestant feast-day for this saint for a discovery made two decades before the start of the Reformation, so the Catholic feast-day of the True Cross on 3 May has been suggested as more likely.[40] Legendarily, Nova anchors on the western side of the island and builds a timber chapel on the location of what will become future Jamestown. Although Saint Helena will become a routine staging post on future India runs, the island's existence and location will remain a Portuguese secret for the next eighty years (until stumbled upon by English captain Sir Thomas Cavendish in 1588).[41]

September 11, 1502 - João da Nova's Third Armada arrives in Lisbon. According to the letters by Italian merchants in Lisbon, the Third Armada had brought back 900 cantari (quintals) of black pepper, 550 of cinnamon, 30 of ginger, 25 of lac, and other assorted goods. The sizeable proportion of cinnamon lends some support to the idea that the armada had visited Ceylon, although it was not unusual to find it on Indian markets. Doubtlessly a good amount of this came also from seized cargos on Malabari and Arab vessels.

Aftermath

The expedition of the Third Armada had not been a resounding success. Although there was no significant loss of ships or men, they came back with less spices than anticipated (letters insinuate that cargo holds came back partially empty) and they had failed to trade for gold in Africa. The report of the cash constraint in India and their reliance on piracy to fill their holds disheartened Lisbon merchants who thought they could make easy profits on both legs of the India run.

On the plus side, the Third Armada's discovery of Ascension and St. Helena islands was welcome, and the latter in particular was to be subsequently used as a staging post on the Atlantic crossing.

All this information was supplied too late to influence Vasco da Gama's heavily armed 4th India Armada, which had already left Lisbon.

Revision of discovery of Ascension and St. Helena

It is customary to credit João da Nova's Third Armada for discovering Ascension island (albeit naming it "Conception Island") on his outward journey in May, 1501, and St. Helena island on his return journey on May 21, 1502. This is principally due to the chroniclers João de Barros and Damião de Góis.[42]

Barros and Gois later suggest that Ascension island was re-discovered by Afonso de Albuquerque's outgoing Fifth Armada on May 20, 1503 and renamed ilha da Ascensção), and that St. Helena was rediscovered by a returning squadron of Vasco da Gama's 4th Armada in the Spring of 1503 (the date is given as July 30, 1503 by eyewitness Thomé Lopes).

Nonetheless, there are some problematic anomalies with this account which suggests some likelihood that Barros and Gois may have been mistaken, and has led modern historians to consider alternative accounts of the discovery of Ascension and St. Helena.

Firstly, in the liturgical calendar, the Feast of Conception is on December 8, while the Feast of the Ascension landed on May 20 in 1501. The latter fits the timing of the Third Armada better. That is, if Nova did indeed find Ascension island on the outward journey, he would be unlikely to have named it "Conception island" and more likely to have named it "Ascension" from the start.

Secondly, the Cantino planisphere, composed in late 1502 (after Nova returned, but before Albuquerque left) already denotes an ilha achada e chamada ascenssam ("island found and called Ascension"), but depicts no St. Helena. This disparity is reinforced by Thomé Lopes, an eyewitness on the returning 4th Armada, who stumbled on St. Helena on July 30, 1503, calling it an "unknown island", and gave its position as 200 leagues away from "Ascension island" (which he refers to by that name).)[43] (Note: the 4th Armada left Portugal before Nova returned).

Because of these anomalies, historian Duarte Leite has discarded Barros and Gois' version, and concluded Nova discovered and named Ascension island on the outgoing voyage on May 20, 1501, but did not discover St. Helena on the return.[44]

This resolution, however, remains doubtful. In particular, there is yet another anomaly - namely, that it would have been nautically bizarre for Nova, on his outgoing journey, to sail from Cape St. Augustine in Brazil to Ascension island, as it implies Nova was sailing directly against the winds and currents, when the usual route to the Cape of Good Hope was to follow the South Atlantic gyre (i.e. bearing south parallel to the Brazilian coast until the Tropic of Capricorn, to catch the Westerlies). On the basis of this, Roukema has proposed that Nova did discover Ascension island, but not on his outgoing voyage, but rather on his return voyage, that is, on May 5, 1502 (when the Ascension day landed in 1502).[45] That this (and not St. Helena) is the island discovered on the return fits better with the winds and trajectory, and helps explain why St. Helena goes unmentioned in the Cantino planisphere. (N.B. - Neither Barros nor Gois suggest Nova stopped in Brazil; this is due solely to Gaspar Correia, who in turn does not report Nova finding any island on the outgoing voyage; so Roukema's insistence that the Third Armada would not have sailed from Brazil to Ascension rests on conflating separate and conflicting chronicles.)

Nonetheless, Roukema agrees that Barros and Gois read reports that Nova discovered some island on his outgoing journey, and conjecture that this was probably the Tristan da Cunha group in the South Atlantic (particularly as Ascension island is shown in the 1502 Cantino planisphere as part of a "group" of islands it calls ilhas tebes, while in reality, Ascension island is solitary). Because Ascension day landed on May 20 in 1501 and St. Helen's day is May 21, this one-day difference may have been the source of confusion of the names in the records, particularly as the return island was indeed discovered on Ascension day. In short, Roukema hypothesizes that Nova discovered and reported the Tristan da Cunha group on the outgoing voyage on May 21, 1501 and called it "St. Helena", and that he discovered Ascension island on the return voyage on May 5, 1502, and called it "Ascension island".[46] But because of the dates, Ascension and the Tristan da Cunha group ("ilhas tebes") were conflated together (as on the Cantino map), with the name St. Helena hovering in and out of the reports, misleading Barros and Gois.

There remain a couple of loose ends. What is Conception island? This has to be a mistake - Nova was in India in December, and there is simply no way of reconciling that with the liturgical calendar. The second question is how did Thomé Lopes know the name "Ascension island" in July 1503, if his ship left Lisbon before Nova returned?[47] A possible resolution to the latter is that Lopes reports coming across the outgoing ships of the 5th Armada of Albuquerque around the Cape of Good Hope in early July 1503.[48] The 5th Armada would have had this information.

Finally, accepting this revision opens the question of who discovered St. Helena proper and when? It is common to cite Estêvão da Gama (Vasco da Gama's cousin), on the returning fleet of the 4th Armada, in early 1503. But this is not exactly correct. The eyewitness account of Thomé Lopes indicates clearly he landed on St. Helena on July 30, 1503. A reading of his account shows that, on St. Helen's day (May 21, 1503), almost all the ships of the 4th Armada (including Estêvão da Gama's ship, the Flor de la mar) were still stuck in Mozambique Island, with severe sailing problems. Vasco da Gama ordered ships off in small waves as they were repaired. Thomé Lopes reports that he departed Mozambique on June 16 with a trio of ships - his ship (commanded by Giovanni Buonagrazia), the Julioa (captained by Lopo Mendes de Vasconcellos) and the Leitoa Nova (captain uncertain, but probably Pedro Afonso de Aguiar, which carried another eyewitness, an anonymous Flemish sailor, who also confirms landing on a South Atlantic island on June 30 (sic)).[49]) Two of these three ships (Buonagrazia's and Vasconcellos's) had indeed gone to India in 1502 as part of a squadron led by Estêvão da Gama, but they were returning in 1503 without him.

The date reported by Lopes - July 30, 1503 - is problematic, as there is no apparent reason to name it "St. Helena" - unless they lingered until August 18 (another possible feast date for St. Helen of Constantinople). Lopes doesn't report a departure date, but the Fleming reports they left August 1. The only other possibility is if St. Helena was first discovered by a different ship of the 4th armada (not the trio that carried Lopes, but another that preceded it in an earlier wave in May.)

This weakens the revised chronologies, and suggests that perhaps Barros and Gois may not have been as mistaken as historians have suggested. Nova's timeline seems adequate enough for the discovery of St. Helena on May 21, 1502.

Notes

- ↑ Radulet (1985: 74n) proposes that Fernão Vinet and Girolamo Sernigi are one and the same person.

- ↑ Barros, 1552: Dec. I, Bk V, c.10, p.464.

- ↑ Góis, 1566: ch. 63 p.83

- ↑ Castanheda, c. 1550s, ch. 63, p.126

- ↑ Couto, "De todas as armadas, &c.", in Barros & Couto, Decadas da Asia, Dec. X, Pt.1, Bk.1, c.16, p.118

- ↑ Faria e Sousa, 1666: vol. 1, Pt. 1, Ch.5, p.50

- ↑ Quintella, 1839: p.257

- ↑ Correia, p.235 Correia refers to Vinet a "Mice Nite Florentym".

- ↑ Relação das Naus p.5; although it notes Barbosa rather than Pacheco in a side-gloss.

- ↑ (Bouchon, 1980: p.250)

- ↑ Faria e Sousa (p.49) reports 400 men. Castanheda reports 80 armed men, "because the king believed that everything in India was at peace, he did not want to send more." (Castanheda, p.126)

- ↑ Subrahmanyam (1997: p.182)

- ↑ Correia, (p.235)

- ↑ Gaspar Correia says March 1, Barros and Gois say March 5, while the letter of Italian agent Lunarda de Cha Masser says April and a letter of King Manuel says April 10. Reviewing the evidence, Duarte Leite suggest an early March date more likely. (Danvers, 1894: p.74)

- ↑ Gaspar Correia (p.235), alone among the chroniclers, mentions this Brazilian stop.

- ↑ Barros (p.466). Correia (p.236) claims the note was left by Sancho de Tovar, and not in a shoe, but under an iron pot.

- ↑ Barros (p.466-67) gets a little confused here, and says the letter told them to go by way of "Mombassa" (an enemy city, evidently he meant Malindi) and that the letters were held by the degredado António Fernandes. Correia (p.236) merely says the note warned of the hostilities with Calicut.

- ↑ Dias Museum, Mossel Bay, Old Post Office Tree

- ↑ Correia (p.236); Subrahmanyam (1997: p.183)

- ↑ cf. Birch, 1877: p.xx)

- ↑ Findlay, A. G. (1866) A Directory for the Navigation of the Indian Ocean, London: Laurie, p.479 online

- ↑ Barros (p.467), Gois (p.84). Correia (p.236) says Esteves was left by Gama and had no letters, that Cabral's letters were being held in Malindi.

- ↑ Correia, p.236

- ↑ Correia, p.237

- ↑ Correia, p.238

- ↑ Correia and Barros agreed on St. Mary islands, but Damião de Góis (p.84) says they landed at Anjediva island and only in November(!)

- ↑ Correia, p.238-39

- ↑ Correia, p.244; Barros (p.468) says Nova tried to seize two ships, but one escaped.

- ↑ Bouchon (1980: p.240) points out there are no surviving contemporary accounts of Portuguese activities in India between the departure of Cabral's return fleet in January 1501 and the arrival of Gama's fourth armada in August 1502. Silence and speculation surrounds Nova's activities in India.

- ↑ Barros (p.476)

- ↑ Correia (p.247)

- ↑ An alternative explanation for the two-month delay may very well be that Nova had realized the cash problem as soon as he arrived in India in August/September, and may have been moving from port to port up there in a frantic search for it. It would certainly help explain why he took to raiding merchant ships so quickly; commercial sense would suggest it would have been best for the Third Armada to proceed quietly and avoid engagements, but their cashlessness left them little choice but to fill their holds by piratical means.

- ↑ Dames (1918: xxxiii).

- ↑ The Cantino planisphere of 1502 clearly shows Ceylon depicted, and that has been cited as another piece of evidence of the Third Armada's visit to the island. However, it is uncertain whether the planisphere was drafted before or after Nova's return (September, 1502). At any rate, the Portuguese could have gotten this information from Joseph the Indian (José de Cranganor, Josephus Indus), the Syrian Christian priest who had returned with Cabral's 2nd Armada in 1501. It was almost certainly Joseph who provided the information that allowed the east coast of India and the Bay of Bengal to be depicted on the map.

- ↑ Date of December 31 is given by Saturnino Monteiro (1989: p.84). Castanheda and Gois date this December 16–17; Correia December 12; Barros asserts they were intercepted during the first leg from Cannanor to Cochin.

- ↑ Matthew (1997: p.11)

- ↑ Marinha.pt, 2009, site Cananor - 31 de Dezembro de 1501 a 2 de Janeiro de 1502

- ↑ Barros (p.477)

- ↑ Barros (p.477); Gois (p.85). This is not reported by Correia.

- ↑ Ian Bruce, ‘St Helena Day’, Wirebird The Journal of the Friends of St Helena, no. 44 (2015): 32–46.

- ↑ Smallman(2003: p.12)

- ↑ Barros (p.466, p.477); Góis (p.p.84, p.85)

- ↑ "On the 30th we saw an island not yet discovered...& between it and the island of Ascension, in the Northwest-Southeast direction, is a distance of 200 leagues from one to the other". Translation from Thomé Lopes. In the Italian version published Ramusio in 1550 (p.156) "Et adi 30 detto vedemmo una isola non discoperta anchora ... & guardasi con l'isole della ascensione maestro & scilocco, & sono 200 leghe di traversa dall'una, all altra.". Or in the 1812 Portuguese translation (Collecção de noticias para a historia e geografia das nações ultramarinas, p.214-15) "Aos trinta houvemos vista de huma ilha ainda não descoberta... com a Ilha da Ascensção tambem de Noroeste a Sueste, e distão duzentas legoas"

- ↑ Leite (1960: p.252-53).

- ↑ Roukema, 1963: p.16

- ↑ Roukema, 1963: p.16

- ↑ This is raised in H. Livermore (2004) "Santa Helena, a Forgotten Portuguese Discovery", in Estudos em Homenagem a Luis Antonio de Oliveira Ramos, Porto, p. 623-31.

- ↑ Lopes (Ital: p.156); Lopes (Port: p.214)

- ↑ The anonymous Flemish sailor bizarrely reports what seems like a horrific massacre on the uninhabited island: "On the 30th day of June we found an island, where we killed at least 300 men, and we caught many of them, and we took there water and departed thence on the 1st day of August" (English trans. in J.P. Berjeau, 1874, Calcoen, a Dutch narrative of the second voyage of Vasco da Gama to Calicut, printed at Antwerp circa 1504. London. p.37. In the original Flemish, it reads "Den. xxx. dach in Iunio soe vonden wij een eylandt en daer sloegen wi wi wel .iij c. mensche doot en vinghen der veel en namen dair water en voeren van daer den eersten dach in Augusto" (p.59). His "men" are probably some sort of birds or turtles, perhaps penguins, the ships were very short of supplies. He also confuses June with July.

Sources

Chronicles

- João de Barros (1552) Décadas da Ásia: Dos feitos, que os Portuguezes fizeram no descubrimento, e conquista, dos mares, e terras do Oriente., 1777–78 ed. Da Ásia de João de Barros e Diogo do Couto, Lisbon: Régia Officina Typografica. Vol. 1 (Dec I, Lib.1-5),

- Diogo do Couto "De todas as Armadas que os Reys de Portugal mandáram à Índia, até que El-Rey D. Filippe succedeo nestes Reynos", de 1497 a 1581", in J. de Barros and D. de Couto, Décadas da Ásia Dec. X, Pt.1, Bk.1, c.16

- Fernão Lopes de Castanheda (1551–1560) História do descobrimento & conquista da Índia pelos portugueses (1833 edition, Lisbon: Typ. Rollandiana v.1

- Gaspar Correia (c. 1550s) Lendas da Índia, first pub. 1858-64, Lisbon: Academia Real de Sciencias Vol 1.

- Damião de Góis (1566–67) Chrónica do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel, da Gloriosa Memoria, Ha qual por mandado do Serenissimo Principe, ho Infante Dom Henrique seu Filho, ho Cardeal de Portugal, do Titulo dos Santos Quatro Coroados, Damiam de Goes collegio & compoz de novo. (As reprinted in 1749, Lisbon: M. Manescal da Costa) online

- Relação das Náos e Armadas da India com os Sucessos dellas que se puderam Saber, para Noticia e Instrucção dos Curiozos, e Amantes da Historia da India (Codex Add. 20902 of the British Library), [D. António de Ataíde, orig. editor.] Transcribed and reprinted in 1985, by M.H. Maldonado, Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra. online

Secondary

- Birch, W. de G. (1877) "Introduction" to translation of Afonso de Albuquerque (1557) The Commentaries of the great Afonso Dalboquerque, second viceroy of India, 4 volumes, London: Hakluyt Society

- Dames, M.L. (1918) "Introduction" in An Account Of The Countries Bordering On The Indian Ocean And Their Inhabitants, Vol. 1 (Engl. transl. of Livro de Duarte de Barbosa), 2005 reprint, New Delhi: Asian Education Services.

- Bouchon, G. (1980) "A propos de l'inscription de Colombo (1501): quelques observations sur le premier voyage de João da Nova dans l'Océan Indien", Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. 28, p. 233-70. Offprint.

- Danvers, Frederic Charles (1894) The Portuguese in India, being a history of the rise and decline of their eastern empire. Vol. 1 (1498–1571) London: Allen.

- Diffie, B. W., and G. D. Winius (1977) Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415-1580, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

- Leite, Duarte (1960) História dos Descobrimentos, Vol. II Lisbon: Edições Cosmos

- Mathew, K.S. (1997) "Indian Naval Encounters with the Portuguese: Strengths and weaknesses", in K.K.N. Kurup, editor, India's Naval Traditions, New Delhi: Northern Book Centre.

- Monteiro, Saturnino (1989) Batalhas e combates da Marinha Portuguesa: 1139-1521 Lisbon: Livraria Sá da Costa

- Quintella, Ignaco da Costa (1839) Annaes da Marinha Portugueza, v.1. Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias.

- Radulet, Carmen M. (1985) "Girolamo Sergini e a Importância Económica do Oriente", Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. 32, p. 67-77. Offprint.

- Report (1899) "Antiquarian Discovery Relating to the Portuguese in Ceylon", Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 16, p. 15-29 Online

- Roukema, E. (1963) "Brazil in the Cantino Map", Imago Mundi, Vol. 17, p.7-26

- Subrahmanyam, S. (1997) The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Smallman, D.K. (2003) Quincentenary: A Story of St Helena,1502-2002. Pezance, UK: Patten.

| Preceded by 2nd Armada (Pedro Álvares Cabral, 1500) |

Portuguese India Armada 3rd Armada (1501) |

Succeeded by 4th Armada (Vasco da Gama, 1502) |