54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

| 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry | |

|---|---|

|

The 54th Massachusetts at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, July 18, 1863 | |

| Active | March 13, 1863 – August 4, 1865 |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch | Union Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 1,100 |

| Nickname(s) | 54th Massachusetts Regiment |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel | Robert Gould Shaw |

| Colonel | Edward Needles Hallowell |

The 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, nicknamed the "Swamp Angels", was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was one of the first official African-American units in the United States during the Civil War.[1] Many African-Americans also had fought in the American Revolution and the War of 1812 on both sides.

History

The regiment was authorized in March 1863 by the Governor of Massachusetts, John A. Andrew. Commanded by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, it was commissioned after the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation.[2] Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton decided white officers would be in charge of all "colored" units.[3] Andrew selected Robert Gould Shaw to be the regiment's colonel and Norwood Penrose "Pen" Hallowell to be its lieutenant colonel.[2] Like many officers of regiments of African-American troops, both Robert Gould Shaw and Hallowell were promoted several grades, both being captains at the time.[2] The rest of the officers were evaluated by Shaw and Hallowell: these officers included Luis Emilio,[4] and Garth Wilkinson "Wilkie" James, brother of Henry James and William James. Many of these officers were of abolitionist families and several were chosen by Governor Andrew himself. Lt. Col. Norwood Hallowell was joined by his younger brother Edward Needles Hallowell who commanded the 54th as a full colonel for the rest of the war after Shaw's death. Twenty-four of the 29 officers were veterans, but only six had been previously commissioned.[5] The soldiers were recruited by white abolitionists (including Shaw's parents). These recruiters included Lieutenant J. Appleton,[6] also the first man commissioned in the regiment, whose recruiting efforts included posting a notice in the Boston Journal.[7] Wendell Phillips and Edward L. Pierce spoke at a Joy Street Church recruiting rally, encouraging free blacks to enlist. About 100 people were actively involved in recruitment, including those from Joy Street Church and a group of individuals appointed by Governor Andrew to enlist black men for the 54th.[8]

The 54th trained at Camp Meigs in Readville near Boston. While there they received considerable moral support from abolitionists in Massachusetts, including Ralph Waldo Emerson.[9] Material support included warm clothing items, battle flags and $500 contributed for the equipping and training of a regimental band. As it became evident that many more recruits were coming forward than were needed, the medical exam for the 54th was described as "rigid and thorough" by the Massachusetts Surgeon-General. This resulted in what he described as "a more robust, strong and healthy set of men were never mustered into the service of the United States."[10] Despite this, as was common in the Civil War, a few men died of disease prior to the 54th's departure from Camp Meigs.

By most accounts the 54th left Boston with very high morale. This was despite the fact that Jefferson Davis' proclamation of December 23, 1862,[11] effectively put both African-American enlisted men and white officers under a death sentence if captured. The proclamation was affirmed by the Confederate Congress in January 1863 and turned both enlisted soldiers and their white officers over to the states from which the enlisted soldiers had been slaves. As most Southern states had enacted draconian measures for "servile insurrection" after Nat Turner's Rebellion, the likely sentence was a capital one.

After muster into federal service on May 13, 1863,[12] the 54th left Boston with fanfare on May 28, and arrived to more celebrations in Beaufort, South Carolina. They were greeted by local blacks and by Northern abolitionists, some of whom had deployed from Boston a year earlier as missionaries to the Port Royal Experiment.[13] In Beaufort, they joined with the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, a unit of South Carolina freedmen led by James Montgomery.[14] After the 2nd Volunteers' successful Raid at Combahee Ferry, Montgomery led both units in a raid on the town of Darien, Georgia.[15] The population had fled, and Montgomery ordered the soldiers to loot and burn the empty town.[16] Shaw objected to this activity and complained over Montgomery's head that burning and looting were not suitable activities for his model regiment.[17]

The regiment's first battlefield action took place in a skirmish with Confederate troops on James Island, South Carolina, on July 16. The regiment stopped a Confederate assault,[18] losing 42 men in the process.

A letter from First Sergeant Robert John Simmons, a former British Army soldier from Bermuda serving in B Company, written shortly before the attack on Battery Wagner, was published in the New York Tribune on the 23rd of December, 1863.[19]

Folly Island, South CarolinaJuly 18, 1863;

We are on the march to Fort Wagner, to storm it. We have just completed our successful retreat from James Island; we fought a desperate battle there Thursday morning. Three companies of us, B, H, and K, were out on picket about a good mile in advance of the regiment. We were attacked early in the morning. Our company was in the reserve, when the outposts were attacked by rebel infantry and cavalry. I was sent out by our Captain in command of a squad of men to support the left flank. The bullets fairly rained around us; when I got there the poor fellows were falling down around me, with pitiful groans. Our pickets only numbered about 250 men, attacked by about 900. It is supposed by the line of battle in the distance, that they were supported by reserve of 3,000 men. We had to fire and retreat toward our own encampment. One poor Sergeant of ours was shot down along side of me; several others were wounded near me. God has protected me through this, my first fiery, leaden trial, and I do give Him the glory, and render my praises unto His holy name. My poor friend [Sergeant Peter] Vogelsang is shot through the lungs; his case is critical, but the doctor says he may probably live. His company suffered very much. Poor good and brave Sergeant (Joseph D.) Wilson of his company [H], after killing four rebels with his bayonet, was shot through the head by the fifth one. Poor fellow... May his brave and noble spirit rest in peace. The General has complimented the Colonel on the galantry and bravery of his regiment.

The regiment gained recognition on July 18, 1863, when it spearheaded an assault on Fort Wagner near Charleston, South Carolina. 272 of the 600 men who charged Fort Wagner were "killed, wounded or captured."[20] At this battle Colonel Shaw was killed, along with 29 of his men; 24 more later died of wounds, 15 were captured, 52 were missing in action and never accounted for, and 149 were wounded. The total regimental casualties of 272 would be the highest total for the 54th in a single engagement during the war. Although Union forces were not able to take and hold the fort (despite taking a portion of the walls in the initial assault), the 54th was widely acclaimed for its valor during the battle, and the event helped encourage the further enlistment and mobilization of African-American troops, a key development that President Abraham Lincoln once noted as helping to secure the final victory. Decades later, Sergeant William Harvey Carney was awarded the Medal of Honor for grabbing the U.S. flag as the flag bearer fell, carrying the flag to the enemy ramparts and back, and singing "Boys, the old flag never touched the ground!" While other African Americans had since been granted the award by the time it was presented to Carney, Carney's is the earliest action for which the Medal of Honor was awarded to an African American.

Ironically, during the week leading up to the 54th's action near Charleston, simmering racial strife climaxed in the New York Draft Riots.[21] African Americans on the city's waterfront and Lower East Side were beaten, tortured, and lynched by white mobs angered over conscription for the Union war effort; rioters mortally wounded the nephew of Sergeant Robert Simmons,[22] who would himself be mortally wounded and captured at Fort Wagner.[23] These mobs directed their animosity toward blacks because they felt the Civil War was caused by them. However, the bravery of the 54th would help to assuage anger of this kind.

Under the command of now-Colonel Edward Hallowell, the 54th fought a rear-guard action covering the Union retreat at the Battle of Olustee. During the retreat, the unit was suddenly ordered to counter-march back to Ten-Mile station. The locomotive of a train carrying wounded Union soldiers had broken down and the wounded were in danger of capture. When the 54th arrived, the men attached ropes to the engine and cars and manually pulled the train approximately three miles (4.8 km) to Camp Finnegan, where horses were secured to help pull the train. After that, the train was pulled by both men and horses to Jacksonville for a total distance of ten miles (16 km). It took forty-two hours to pull the train that distance.[2]

As part of an all-black brigade under Col. Alfred S. Hartwell, they unsuccessfully attacked entrenched Confederate militia at the November 1864 Battle of Honey Hill. In mid-April 1865, they fought at the Battle of Boykin's Mill, a small affair in South Carolina that proved to be one of the last engagements of the war.

Pay controversy

The enlisted men of the 54th were recruited on the promise of pay and allowances equal to their white counterparts. This was supposed to amount to subsistence and $13 a month.[24] Instead, they were informed upon arriving in South Carolina, the Department of the South would pay them only $7 per month ($10 with $3 withheld for clothing, while white soldiers did not pay for clothing at all.)[25] Colonel Shaw and many others immediately began protesting the measure.[26] Although the state of Massachusetts offered to make up the difference in pay, on principle, a regiment-wide boycott of the pay tables on paydays became the norm.[27]

After Shaw's death at Fort Wagner, Colonel Edward Needles Hallowell took up the fight to get back full pay for the troops.[28] Lt. Col. Hooper took command of the regiment starting June 18, 1864. After nearly a month Colonel Hallowell returned on July 16.[29]

Refusing their reduced pay became a point of honor for the men of the 54th. In fact, at the Battle of Olustee, when ordered forward to protect the retreat of the Union forces, the men moved forward shouting, "Massachusetts and Seven Dollars a Month!"[2]

The Congressional bill, enacted on June 16, 1864, authorized equal and full pay to those enlisted troops who had been free men as of April 19, 1861. Of course not all the troops qualified. Colonel Hallowell, a Quaker, rationalized that because he did not believe in slavery he could therefore have all the troops swear that they were free men on April 19, 1861. Before being given their back pay the entire regiment was administered what became known as "the Quaker oath".[28] Colonel Hallowell skillfully crafted the oath to say: "You do solemnly swear that you owed no man unrequited labor on or before the 19th day of April 1861. So help you God".[28][30]

On September 28, 1864, the U.S. Congress took action to pay the men of the 54th. Most of the men had served 18 months.[29]

Legacy

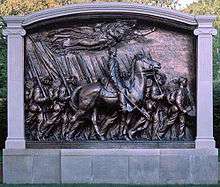

A monument, constructed 1884–1898 by Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the Boston Common, is part of the Boston Black Heritage Trail.[31] A plaster of this monument was also displayed in the entryway to the U.S. paintings galleries at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900.[32]

Of the regiment, Governor John A. Andrew said:

I know not where, in all of human history, to any given thousand men in arms there has been committed a work at once so proud, so precious, so full of hope and glory.[33]

A famous composition by Charles Ives, "Col. Shaw and his Colored Regiment", the opening movement of Three Places in New England, is based both on the monument and the regiment.[31]

Colonel Shaw and his men also feature prominently in Robert Lowell's Civil War Centennial poem "For the Union Dead" (1964). Originally in "Colonel Shaw and the Massachusetts' 54th", published in Life Studies (1959), Lowell invokes the realism of the Saint-Gaudens monument:[31]

- Two months after marching through Boston,

- half the regiment was dead;

- at the dedication,

- William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe.

Six stanzas later, Lowell looks unflinchingly at Shaw's and his men's death:[31]

- Shaw's father wanted no monument

- except the ditch,

- where his son's body was thrown

- and lost with his "men"

A Union officer had asked the Confederates at Battery Wagner for the return of Shaw's body, but was informed by the Confederate commander, Brigadier General Johnson Hagood, "We buried him with his niggers."[34] Shaw's father wrote in response that he was proud that Robert, a fierce fighter for equality, had been buried in that manner.[35] "We hold that a soldier's most appropriate burial-place is on the field where he has fallen."[36] As a recognition and honor, at the end of the Civil War, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, and the 33rd Colored Regiment were mustered out at the Battery Wagner site of the mass burial of the 54th Massachusetts.

More recently, the story of the unit was depicted in the 1989 Academy Award-winning film Glory, starring Matthew Broderick as Shaw, Denzel Washington as Private Tripp, Morgan Freeman, Cary Elwes, Jihmi Kennedy and Andre Braugher.[37]

The film re-established the now-popular image of the combat role African Americans played in the Civil War, and the unit, often represented in historical battle reenactments, now has the nickname the "Glory" regiment.[31]

2008 reactivation

The unit was reactivated on November 21, 2008, to serve as the Massachusetts National Guard ceremonial unit to render military honors at funerals and state functions. The new unit is now known as the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment.[38]

See also

- First Sergeant Robert John Simmons, of B Company, from Bermuda

- Glory (1989 film)

Footnotes

- ↑ "54th Regiment!". Massachusetts historical Society. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Emilio 1995, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Bielakowski 2013, p. 202.

- ↑ Cox 1991, p. 90.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ Burchard 1965, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ "To Colored Men. 54th Regiment! Massachusetts Volunteers, Of African Descent". Massachusetts Historical Society. 16 February 1863.

To Colored Men: Wanted. Good men for the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers of African descent, Col. Robert G. Shaw (commanding). $100 bounty at expiration of term of service. Pay $13 per month, and State aid for families. All necessary information can be obtained at the office, corner Cambridge and North Russell Streets.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, p. 11.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis's Proclamation Regarding Captured Black Soldiers, December 23, 1862". University of Maryland, College Park. Archived from the original on 2012-10-25. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "Battle Unit Details - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ↑ Rose 1964, pp. 248249.

- ↑ Rose 1964, pp. 250–249.

- ↑ Rose 1964, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Rose 1964, p. 252.

- ↑ Rose 1964, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, pp. 51–57.

- ↑ "BCF « Written in Glory".

- ↑ "Exhibit: 54th Mass Casualty List". National Archives and Records Administration. 1996. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "Even more crushing to Negro soldiers must have been the ugly news from New York. At the very time the 54th had been fighting doggedly about Charleston harbor, a furious mob, angered over the draft policy of the government, had vented its spleen on the hapless Negroes of the city. Ugly indeed was the thought that while they had been fighting at the front, black people were being lynched in the North, and that a Negro orphanage had been burned." Rose 1964, p. 262

- ↑ Cox 1991, p. 69.

- ↑ Cox 1991, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Emilio 1991, pp. viii–ix, 8–9.

- ↑ Rose 1964, p. 261.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, pp. 47–48, 109.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, pp. 130–131, 136–138.

- 1 2 3 McPherson 1964, pp. 217–218.

- 1 2 "Lt. Col. Henry N. Hooper, 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry". Florida Department of Environmental Protection – Recreation and Parks and the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park Citizens Support Organization. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Fuller 2001, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joseph R. Laplante, Standard Times staff writer. "The 54th Regiment: Black soldiers remembered in bronze, prose and song". South Coast Today. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Fischer, Diane P. (1999). Paris 1900: The "American School" at the Universal Exposition. Rutgers University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8135-2640-X.

- ↑ Emilio 1995, p. Title page verso.

- ↑ Burchard 1989, p. 143.

- ↑ Buescher, John. "Robert Gould Shaw". Teachinghistory.org. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Brown 1867, p. 380.

- ↑ Glory at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Tierney McAffee (January 14, 2009). "54th Mass. Regiment to march in inaugural parade.". The Bay State Banner.

Sources

- Bielakowski, Alexander M. (2013). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-427-6.

- Egerton, Douglas (2016). Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465096640.

- Brown, William Wells (1867). The Negro in the American Rebellion: His Heroism and His Fidelity. Boston: Lee & Shepherd.

- Burchard, Peter (1989). One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw and his Brave Black Regiment. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312046439.

- Cox, Clinton (1991). Undying Glory: The Story of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. New York: Scholastic. ISBN 978-0590441711.

- Emilio, Luis F. (1995) [1891]. A Brave Black Regiment: the history of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863–1865. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306806230.

- Fuller, James (2001). Men of Color, To Arms!: Vermont African-Americans in the Civil War. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595158263.

- McPherson, James (1964). The Struggle for Equality. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Rose, Willie Lee (1964). Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Further reading

- Shaw, Robert Gould (1999). Duncan, Russell, ed. Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. Athens, Ga: University of Georgia Press.

External links

- "Louisiana and Massachusetts – Abraham Lincoln and Freedom". The Lincoln Institute. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- "Exhibit: 54th Mass Casualty List". National Archives and Records Administration. 1996. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Written in Glory, Letters from the Soldiers and Officers of the 54th Massachusetts

- 54th Massachusetts at the Battle of Olustee

- Photograph of Sgt. Major Lewis Douglass

- Photograph of Charles Douglass

- History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863–1865 (1894) on the Internet Archive

- American Civil War Battles of Fort Wagner