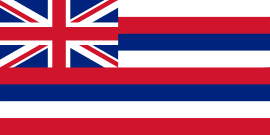

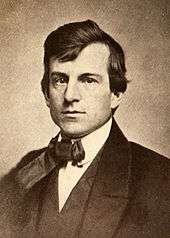

Alfred S. Hartwell

| Alfred Stedman Hartwell | |

|---|---|

Alfred S. Hartwell | |

| Born |

June 11, 1836 South Natick, Massachusetts. |

| Died |

August 30, 1912 (aged 76) Honolulu |

| Occupation | Soldier, Judge, Lawyer |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Elizabeth "Lottie" Smith |

| Children | 8 |

Alfred Stedman Hartwell (June 11, 1836 – August 30, 1912) was a lawyer and American Civil War soldier, who then had another career as cabinet minister and judge in the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Life

Alfred Stedman Hartwell was born June 11, 1836 in South Natick, Massachusetts. His father was Stedman Hartwell and mother was Rebecca Dana Perry (1805–1872).[1] He graduated from Harvard University in 1858 where he was elected into the Phi Beta Kappa Society.[2]

War

He moved to St. Louis, Missouri and worked as an instructor at Washington University. In April 1861, at the outbreak of the American Civil War, he enlisted as Corporal in the Third Missouri Reserve regiment. Missouri was officially neutral but supporters of the Confederacy had captured Liberty Arsenal, and his company was called up to help recapture the weapons. This resulted in the Camp Jackson Affair.[3]

In June he returned to Boston and enrolled in Harvard Law School, but by September 1862 became a First Lieutenant in the 44th Massachusetts regiment. When the United States Colored Troops (USCT) were formed for African-American recruits, he was promoted to Captain on March 31, 1863 of the 54th Massachusetts. However, the number of volunteers was higher than expected, so he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and helped organize the 55th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry under command of Norwood Penrose Hallowell. The 54th's role in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner was depicted in the film Glory. The 55th moved into their former barracks, and was ordered to embark in July 1863. They served building trenches on Folly Island supporting the siege of Charleston, South Carolina. When Hallowell had to resign for treatment of an old wound, Hartwell was promoted to command the regiment on November 3, 1863.[3]

Morale became a problem when his troops discovered that despite being promised the same pay as their white counterparts, they had a major deduction for a "clothing allowance". Hartwell complained to his commanding officers, and suggested promoting African-American troops to officers. On May 24, 1864 he commissioned John Freeman Shorter to be a second Lieutenant, but it was refused by General John Porter Hatch. He protested up to the Secretary of War and threatened to resign, until the pay issue was settled in August 1864.[4]

In the Battle of Honey Hill on November 30, 1864 he commanded a brigade that included the 55th and 54th Massachusetts and the 102nd USCT. He was wounded and had his horse shot from under him leading three charges. Captain Thomas F. Ellsworth received the Congressional Medal of Honor because "Under a heavy fire [Ellsworth] carried his wounded commanding officer [Hartwell] from the field." The battle was generally a failure, but proved another example where the African-American troops could be used in battle.[5] On January 23, 1865,[6] President Abraham Lincoln nominated Hartwell for the award of the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general, to rank from December 30, 1864, for gallant services at the battle of Honey Hill.[7] The U.S. Senate confirmed the award on February 14, 1865.[6]

On January 30, 1865 he rejoined his brigade, and in February 1865 he commanded the brigade in an attack on James Island, South Carolina (see Battle of Grimball's Causeway). After a few skirmishes, both sides retreated.[8] After the fall of Charleston, he marched his forces through the city, with the African-American troops at the head of his brigade. They occupied the city and dealt with the large number of refugees.

On April 5, 1865 he commanded another combined force that marched through Charleston again, although by now the Confederate army was generally dispersing. Their duties now were mostly peace-keeping and rebuilding bridges.[9] On May 1 his units were based in Orangeburg, South Carolina, and finally in June his promotions of black officers were finally approved. In August the 55th was taken out of service. However, Hartwell was sent to investigate Milton S. Littlefield who was accused of fraud (known as the "Prince of carpetbaggers").[10]

He was finally discharged on April 30, 1866. He returned to Boston, and was elected to the legislature of Massachusetts as a Republican. After the war he finished his last year of law school and graduated with an LLB degree from Harvard in 1867. He briefly started a law practice in Boston with classmate Samuel Craft Davis.[11] On August 15, 1868 he left at the suggestion of fellow Massachusetts lawyer Elisha Hunt Allen, intending to spend a year or two on an adventure to the Hawaiian Islands.[2]

Hawaii

He was appointed by King Kamehameha V to the supreme court of the Kingdom of Hawaii on the day he landed, September 30, 1868.[12]

There were so few trained lawyers in Hawaii, one of the other supreme court justices, Hermann A. Widemann, had never been to law school. Elisha Hunt Allen was still acting as chief justice, despite living in the United States much of the time.[13] He rented a room at Washington Place from Mary Dominis. Also living there was John Owen Dominis who was Governor of Oahu, and his wife Lydia, the future Queen Liliʻuokalani. He quickly learned the Hawaiian language and by December 1868 was instructing juries as a circuit court judge without an interpreter.[2] At the time, the supreme court was trial court for several kinds of cases, handled appeals, and its judges acted as circuit judges on other islands.

He married Charlotte Elizabeth "Lottie" Smith (1845–1896) on January 10, 1872 in Kōloa on Kauaʻi island. Her father was missionary physician James William Smith who arrived in 1842 to Hawaii. Her brother was lawyer William Owen Smith (1848–1929)[14] who later joined him in law practice.[15] They had eight children:

- Daughter Mabel Rebecca Hartwell was born April 5, 1873 and married Alfred Townsend in 1897.

- Daughter Edith Millicent Hartwell was born May 25, 1874 and married Alfred Wellington Carter (1867–1949) in 1895.[16]

- Daughter Madeline Perry Hartwell was born May 26, 1875 and married Albert Francis Judd, Jr. in 1899, son of Albert Francis Judd, and grandson of Gerrit P. Judd.

- Daughter Charlotte Lee Hartwell was born October 22, 1876 and married Charles Henry Chater.

- Daughter Juliette Hartwell was born July 27, 1879 and married Olaf L. Sorenson on May 18, 1912.

- Son Charles Atherton Hartwell was born November 5, 1880 and married Cordelia Judd Carter (1876–1921), daughter of Henry A. P. Carter, cousin of A. W. Carter, and granddaughter of Gerrit.[16]

- Bernice Hartwell was born August 15, 1882.

- Alice Dorothy Hartwell was born July 27, 1884 and married Ferdinand Frederick Hedemann in 1927.[17]

For his honeymoon the couple traveled first to San Francisco in February 1872, where he found out his father had died on his wedding day. When they arrived in Natick, his mother was also ill, and they stayed until she died on June 11, 1872. They returned and rented a house in Honolulu in August 1872. In 1873 he hosted a visit of some other former civil war generals, including John Schofield, Rufus Ingalls, and Barton S. Alexander, when they investigated the use of Pearl Harbor as a naval base. As King Lunalilo was dying, Hartwell advised him to name a clear successor, assuming it would be Queen Emma of Hawaii. However, Lunalilo died before naming an heir to the throne, resulting in a political crisis when the popular Emma was not elected.[2]

Hartwell was appointed Attorney General by King Kalākaua on February 18, 1874 replacing Albert Francis Judd (who moved onto the court), but was replaced on May 28.[18] On December 5, 1876 he was appointed again, replacing William Richards Castle. This time he served until July 3, 1878,[12] when he went into private practice. Hartwell suspected that Claus Spreckles had him removed because Hartwell was opposed to Spreckles plans to license water rights for his sugarcane plantations. In 1883 he closed his practice and traveled back to Boston, but returned to Hawaii in 1885.[13]

.jpg)

In late 1890 he traveled to Washington, DC to negotiate on a cable connection between Hawaii and west coast of the United States. Although he did not support the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, he did lobby for its annexation to the US. In 1899 he traveled to Washington, DC as unofficial representative until Robert William Wilcox was elected.[19] On the same trip he attended the International commercial congress in Philadelphia.[20] In 1895 Hartwell wrote the document signed by Liliʻuokalani in which she agreed to abdicate, avoiding death sentences for those (including herself) convicted after the 1895 Counter-Revolution in Hawaii. Liliʻuokalani remained bitter about what she saw as a former friend working for her enemies.[21]

He formed a law form with Lorrin Andrews Thurston, one of the leaders of the overthrow, and then added his assistant William F. L. Stanley.[22] In 1901 he was hired to challenge the income tax in the Hawaii territorial court.[23] His daughter's brother-in-law George Robert Carter became Territorial Governor of Hawaiʻi in 1903. On June 15, 1904, he was appointed again to the Supreme Court of what was now the US Territory of Hawaii, and became chief justice August 15, 1907.[12] He replaced Walter F. Frear who in turn replaced Carter as Governor.

On March 9, 1911 he resigned and left in June for a vacation in Europe, but became ill in London and returned to Hawaii. He died in Honolulu on August 30, 1912 and was buried in Oahu Cemetery.[2]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred S. Hartwell. |

References

- ↑ Carlos Slafter (1905). A record of education: the schools and teachers of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1644-1904. Dedham Transcript Press. p. 126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alfred Stedman Hartwell (1946) [1908]. "Forty Years of Hawaii Nei". Fifty-fourth Annual Report. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 7–24. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- 1 2 James Lorenzo Bowen (1889). "Brevet Brigadier General Alfred S. Hartwell". Massachusetts in the war, 1861-1865. C. W. Bryan & Company. pp. 934–935.

- ↑ Jonathan Sutherland (2004). "55th Massachusetts Regiment Infantry (Civil War)". African Americans at war: an encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-1-57607-746-7.

- ↑ Jonathan Sutherland (2004). "Honey Hill, Battle of (November 30, 1864)". African Americans at war: an encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 217–219. ISBN 978-1-57607-746-7.

- 1 2 Eicher, John H. and Eicher, David J. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001, p. 747. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- ↑ Hunt, Roger D. and Brown, Jack R. Brevet Brigadier Generals in Blue, p. 268. Gaithersburg, MD: Olde Soldier Books, Inc., 1990. ISBN 1-56013-002-4.

- ↑ United States War Records Office (1895). The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies. Government Printing Office. pp. 1042–1043.

- ↑ Record of the service of the Fifty-fifth regiment of Massachusetts. Gale Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4328-1780-0.

- ↑ Jonathan Daniels (1974). Prince of carpetbaggers. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-7466-2.

- ↑ The report of the secretary of the Class of 1863 of Harvard College. University Press. 1888. p. 55.

- 1 2 3 "Hartwell, Alfred Stedman office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- 1 2 Hawaii. Supreme Court (1914). "In the Matter of the Presentation of Resolutions on the Death of the Late Honorable Alfred S. Hartwell". Hawaiian reports: cases decided in the Supreme Court of the Territory of Hawaii. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. pp. 781–794.

- ↑ "Smith Family Records" (PDF). Kauaʻi Historical Society. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ↑ "William Owen Smith (1848-1929)". Kamehameha Schools Archives. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- 1 2 George Robert Carter (1915). Joseph Oliver Carter: the founder of the Carter family in Hawaii, with a brief genealogy. Hawaiian Historical Society. pp. 10–12.

- ↑ "Catherine Cinderella HARTER - Lewis HERMANS". Alice Dorothy HARTWELL. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ↑ "Attorney General office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Hawaii to Send an Agent: Judge Hartwell Chosen as Representative at Washington" (pdf). new York Times. September 23, 1899. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ↑ Official proceedings of the International commercial congress: a conference of all nations for the extension of commercial intercourse. Press of the Philadelphia commercial museum. 1899. p. 390.

- ↑ Liliʻuokalani (Queen of Hawaii) (July 25, 2007) [1898]. Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen, Liliuokalani. Lee and Shepard, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2.

- ↑ "Local Brevities". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. December 5, 1895. p. 5. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Income Tax Before the Supreme Court: It Must be Levied or the Government Can't Go on". The Honolulu republican. Honolulu. August 14, 1901. p. 5. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

External links

- "Alfred S. Hartwell". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Kathy Dhalle (August 2006). "Alfred Stedman Hartwell". Bits of Blue and Gray. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- Kathy Dhalle (April 1995). "History of the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry". Lest We Forget Volume 3, Number 2. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Albert Francis Judd |

Kingdom of Hawaii Attorney General February 1874 – May 1874 |

Succeeded by Richard H. Stanley |

| Preceded by William Richards Castle |

Kingdom of Hawaii Attorney General December 1876 – July 1878 |

Succeeded by Edward Preston |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by Walter F. Frear |

Territory of Hawaii Supreme Court Chief Justice August 1907 – March 1911 |

Succeeded by Alexander G. M. Robertson |