Alcohol in New Zealand

Alcoholic beverages have been drunk in New Zealand since the early days of European arrival. New Zealand has no minimum consumption age for alcohol, however the minimum purchase age is 18.[1]

History

Temperance movement

Between 1836 and 1919, the New Zealand temperance movement became a powerful and popular lobby group, as similar movements did in the UK and the USA. In 1919 at a national referendum poll, prohibition gained 49% of the vote and was only defeated when the votes of returned servicemen were counted.[2]

Well known temperance activists in New Zealand include William Fox, Frank Isitt, Leonard Isitt, Elizabeth McCombs, James McCombs, Kate Sheppard, Robert Stout and Tommy Taylor.

Consumption

Beer

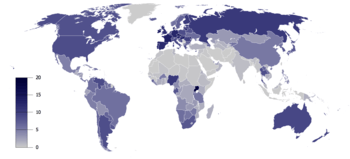

Beer is the most popular alcoholic drink in New Zealand, accounting for 63% of available alcohol for sale.[3] New Zealand is ranked 21st in beer consumption per capita, at around 75.5 litres per person per annum. The vast majority of beer produced in New Zealand is a type of lager, either pale or amber in colour, and between 4%–5% alcohol by volume.

Alcohol law

First Liquor Laws

The liquor laws of New Zealand begin with the Colonisation of New Zealand and the implementation of English Common Law to New Zealand between 1840 and 1842, when New Zealand was jurisdictionally part of the Colony of New South Wales.[4]

Laws for Maori

The First Laws regarding the prevention of Maori from consuming alcohol in New Zealand were established between 1847 and 1878. Laws were passed due to the common belief the Maori were susceptible to alcohol.[4]

For 100 years, from the 1847 laws to 1947, Maori were restricted to buying alcohol from off-licensed vendors. In 1947 Maori were given a right to drink alcohol.

Laws for Women

Prior to 1961, Women were restricted to buying alcohol from off-licensed vendors and private bars in hotels due to legislation denying them a right to drink publicly.

Regulation and Licensing

In 1842 the first licensing system was introduced to New Zealand. This licensing system was mainly based on the then-provincial councils, however this changed in 1873 when legislature was passed to establish a national licensing system.[4]

Until the 1990s off-licence alcohol sales where restricted to hotels, bottle shops, and private clubs were also allowed to sell alcohol for take home consumption. In 1990 supermarkets were granted permission to sell wine but not beer, but under amendments made in 1999,[5] supermarkets and some smaller grocers now had permission to extend there liquor licences to sell beer as well as wine.

The 1999 legislation also legalized the sale of alcohol on Sundays for the first time in nearly 120 years.[5]

Licensing Act, 1881

The Licensing Act of 1881 was enacted due to the dissolution of the Provincial Councils of New Zealand to centralize the inconsistent statutes of the former Provinces.[4]

The Licensing Act of 1881 banned some entertainments, including dancing girls. Section 127 stated: ‘Whereas a practice exists in certain parts of the colony of hiring women and young girls to dance in rooms and places where liquors are sold: any contract by which any females shall be hired to dance in any such room or place shall be null and void.’ Proprietors risked having their establishment identified as a ‘disorderly house’ (a brothel), receiving a fine or losing their liquor license if they hired dancing girls.[4]

The Act banned alcohol sales on Sundays, Christmas Day, and Good Friday.[4]

Legal Ages

The first registered consumption age limits were imposed for the first time meaning nobody under the age of 18 could drink in a public bar and nobody under the age of 13 could buy alcohol to take home.

The Licensing Act of 1881 created a minimum age of 16 to purchase alcohol in a bar, however did not impose a minimum age to purchase alcohol to be taken away.[4]

The legal drinking age was again amended in 1910 when the legal age to drink in hotels was increased to 21 - however minors could still buy alcohol to take home until 1914 when the age for both on and off licence purchase was set at 21.

In 1969 the purchase and public consumption age was lowered from 21 to 20. (although 18 year olds where allowed to drink in bars from 1990 on certain conditions.) But in 1999 the legal purchasing age was lowered from 20 to 18 and despite several calls and legislation to raise the drinking age again, Lawmakers have overwhelmingly favoured the status quo and the age remains 18. It has never been illegal for a minor to drink alcohol in their own home on supervision of their parents or guardians however in 2013, minors consuming alcohol in a private setting other than their homes had to acquire parental permission before doing so.

Six O'clock Swill

The most significant piece of alcohol legislation introduced in new Zealand was the Six O'clock Swill in 1917. Intended to only be a temporary wartime measure through the remainder of World War One, this new law required all hotel bars to close at 6pm nightly (and all day Sunday).

The Swill was made permanent in 1919 owing to pressure from the then powerful temperance movement. The new law was supposed to curb drunkenness and crime and to send men home early to encourage family life, however Six O'clock closing had the opposite effect. Men would finish work at 5pm and had only one hour to drink as much alcohol (usually beer and from half gallon (1.9 litre) jugs) as possible before closing. This phenonomen created a culture of binge drinking.

The six o'clock swill also encouraged men to drive home from the hotels extremely drunk and car crashes where the most common between 6pm and 8pm especially on Friday and Saturday evenings. This was not helped by the fact New Zealand had no realistic Blood Alcohol limits for driving until 1969.

The six o'clock swill ended on 9 October 1967 when pubs could stay open until 10pm after a referendum on 26 September overwhelmingly saw voters favour change. A Previous referendum in 1949 rejected later closing (due to economic rather than moral reasons).

Special Events

Under New Zealand law, pubs looking to operate after the 3-4am liquor sales ban will have to apply for special licencing from their local board.[6]

Licensing trusts

Licensing trusts, under New Zealand law, are community-owned companies with a monopoly on the development of premises licensed for the sale of alcoholic beverages and associated accommodation in an area.[7]

Production

Beer

Early history

There is no oral tradition or archaeological evidence of Māori brewing beer before the arrival of Europeans. Major ingredients of beer were not introduced to New Zealand until Europeans arrived in the late-18th century. Captain James Cook brewed a beer flavoured with local spruce tree needles while visiting New Zealand in 1773 in order to combat scurvy aboard ship.[8] He brewed the beer while anchored in Ship Cove in the outer reaches of Queen Charlotte Sound in January 1770. Here he experimented with the use of young rimu branches as a treatment against scurvy. It was brewed on Saturday 27 March 1773 on Resolution Island, in Dusky Sound, Fiordland. The beer was brewed using wort with addition of molasses and rimu bark and leaves. James Cook wrote:

"We also began to brew beer from the branches or leaves of a tree, which much resembles the American black-spruce. From the knowledge I had of this tree, and the similarity it bore to the spruce, I judged that, with the addition of inspissated juice of wort and molasses, it would make a very wholesome beer, and supply the want of vegetables, which this place did not afford; and the event proved that I was not mistaken."[9]

The first commercial brewery in New Zealand was established in 1835 by Joel Samuel Polack in Kororareka (now Russell) in the Bay of Islands. During the 19th century, New Zealand inherited the brewing traditions and styles of the United Kingdom and Ireland, being where the majority of European immigrants originated from during that time – thus the dominant beer styles would have been ales, porters & stouts.

20th century

The culture of the six o'clock swill was to have an influence on the styles of beer brewed and drunk in New Zealand. In the 1930s, the New Zealander Morton W. Coutts invented the continuous fermentation process. Gradually, beer production in New Zealand shifted from ales to lagers, using continuous fermentation. The style of beer made by this method has become known as New Zealand Draught, and became the most popular beer during the 6 o'clock swill period.

During the same period, there was a gradual consolidation of breweries, such that by the 1970s virtually all brewing concerns in New Zealand were owned by either Lion Breweries or Dominion Breweries. From the 1980s small boutique or microbreweries started to emerge, and consequently the range of beer styles being brewed increased. The earliest was Mac's Brewery, started in 1981 in Nelson. Some pubs operated their own small breweries, often housed within the pub itself.

21st century

In recent years, pale and amber lager, the largest alcoholic drinks sector in terms of volume sales, have been on a downward trend as a result of a declining demand for standard and economy products.[10]

Conversely, ale production in New Zealand is primarily undertaken by small independent breweries & brewpubs, the Shakespeare Brewery in Auckland city being the first opened in 1986 for the 'craft' or 'premium' sector of the beer market. In 2010, this 'craft/premium' sector grew by 11%, to around 8% of the total beer market.[3] This has been in a declining beer market, where availability of beer has dropped 7% by volume in the two previous years.

Craft beer and microbreweries were blamed for a 15 million litre drop in alcohol sales overall in 2012, with Kiwis opting for higher-priced premium beers over cheaper brands.[11]

The craft beer market in New Zealand is varied and progressive, with a full range of ale & lager styles of beer being brewed. New Zealand is fortunate in that it lies in the ideal latitude for barley and hops cultivation. A breeding programme had developed new hop varieties unique to New Zealand,[12] many of these new hops have become mainstays in New Zealand craft beer.

Given the small market and relative high number of breweries, many breweries have spare capacity. A recent trend has seen the rise of contract brewing, where a brewing company contracts to use space in existing breweries to bring the beer to the market. Examples of contract brewers include Funk Estate, Epic Brewing Company and Yeastie Boys.[13]

Over 2011 and 2012, New Zealand faced a shortage of hops, which affected several brewers countrywide, and was mainly due to a hop shortage in North America and an increase in demand for New Zealand hops overseas.[14][15]

Wine

Early history

Wine making and vine growing go back to colonial times in New Zealand. British Resident and keen oenologist James Busby was, as early as 1836, attempting to produce wine at his land in Waitangi.[16] In 1851 New Zealand's oldest existing vineyard was established by French Roman Catholic missionaries at Mission Estate in Hawke's Bay.[17] Due to economic (the importance of animal agriculture and the protein export industry), legislative (prohibition and the temperance) and cultural factors (the overwhelming predominance of beer and spirit drinking British immigrants), wine was for many years a marginal activity in terms of economic importance. Dalmatian immigrants arriving in New Zealand at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century brought with them viticultural knowledge and planted vineyards in West and North Auckland. Typically, their vineyards produced sherry and port for the palates of New Zealanders of the time, and table wine for their own community.

The three factors that held back the development of the industry simultaneously underwent subtle but historic changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1973, Britain entered the European Economic Community, which required the ending of historic trade terms for New Zealand meat and dairy products. This led ultimately to a dramatic restructuring of the agricultural economy. Before this restructuring was fully implemented, diversification away from traditional protein products to products with potentially higher economic returns was explored. Vines, which produce best in low moisture and low soil fertility environments, were seen as suitable for areas that had previously been marginal pasture. The end of the 1960s saw the end of the New Zealand institution of the "six o'clock swill", where pubs were open for only an hour after the end of the working day and closed all Sunday. The same legislative reform saw the introduction of BYO (bring your own) licences for restaurants.

Finally the late 1960s and early 1970s noted the rise of the "overseas experience," where young New Zealanders travelled and lived and worked overseas, predominantly in Europe. As a cultural phenomenon, the overseas experience predates the rise of New Zealand's premium wine industry, but by the 1960s a distinctly New Zealand identity had developed and the passenger jet made the overseas experience possible for a large numbers of New Zealanders who experienced first-hand the premium wine cultures of Europe.

First steps

In the 1970s, Montana in Marlborough started producing wines which were labelled by year of production (vintage) and grape variety (in the style of wine producers in Australia). The first production of a Sauvignon blanc of great note appears to have occurred in 1977. Also produced in that year were superior quality wines of Muller Thurgau, Riesling and Pinotage. The excitement created from these successes and from the early results of Cabernet Sauvignon from Auckland and Hawkes Bay launched the industry with ever increasing investment, leading to more hectares planted, rising land prices and greater local interest and pride. Such was the boom that over-planting occurred, particularly in the "wrong" varietals that fell out of fashion in the early 1980s. In 1984 the then Labour Government paid growers to pull up vines to address a glut that was damaging the industry. Ironically many growers used the Government grant not to restrict planting, but to swap from less economic varieties (such as Müller Thurgau and other hybrids) to more fashionable varieties (Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc), using the old root stock. The glut was only temporary in any case, as boom times returned swiftly.

Sauvignon blanc breakthrough

New Zealand is home to what many wine critics consider the world’s best Sauvignon blanc. Oz Clarke, a well-known British wine critic wrote in the 1990s that New Zealand Sauvignon blanc was "arguably the best in the world" (Rachman). Historically, Sauvignon blanc has been used in many French regions in both AOC and Vin de Pays wine. The most famous had been France’s Sancerre. It is also the grape used to make Pouilly Fumé. Following Robert Mondavi's lead in renaming Californian Sauvignon blanc Fumé Blanc (partially in reference to Pouilly Fumé and partially to denote the smokiness of the wine produced due to flinty soil properties and partial oak barrel ageing) there was a trend for oaked Sauvignon blanc in New Zealand during the late 1980s. Later the fashion for strong oaky overtones and also the name waned. In the 1980s, wineries in New Zealand, especially in the Marlborough region, began producing outstanding, some critics said unforgettable, Sauvignon blanc. "New Zealand Sauvignon blanc is like a child who inherits the best of both parents—exotic aromas found in certain Sauvignon blancs from the New World and the pungency and limy acidity of an Old World Sauvignon blanc like Sancerre from the Loire Valley" (Oldman, p. 152). One critic said that drinking one's first New Zealand Sauvignon blanc was like having sex for the first time (Taber, p. 244). "No other region in the world can match Marlborough, the northeastern corner of New Zealand's South Island, which seems to be the best place in the world to grow Sauvignon blanc grapes" (Taber, p. 244).

See also

- New Zealand cuisine

- Hokonui Hills, an area renowned for illicit alcohol production during the nineteenth century

- List of countries by alcohol consumption

- New Zealand alcohol licensing referendums 1894–1987

References

- Oldman, Mark. Oldman's Guide to Outsmarting Wine. NY: Penguin, 2004.

- Rachman, Gideon. "The globe in a glass". The Economist, 16 December 1999.

- Sogg, Daniel. "Standout Sauvignons", Wine Spectator, 10 November 2005, p. 108-111.

- Taber, George M. Judgment of Paris: California vs France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine. NY: Scribner, 2005.

- ↑ Bartistich, Marija. "Under 18s and the Law". Cheers.co.nz. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "Voting for prohibition" www.nzhistory.net.nz, retrieved 14 June 2011

- 1 2 Carroll, Joanne (20 March 2011). "Beer hops off buyers' lists". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand": 1. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- 1 2 Government of New Zealand, Her Majesties. "Sale of Liquor Amendment Act, 1999". legislation.govt.nz. Legislation New Zealand. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.nzherald.co.nz/brewing-and-liquor-industry/news/article.cfm?c_id=136&objectid=11465456

- ↑ "Opposition's voice heard on liquor bill". The New Zealand Herald (NZPA). 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ↑ Archived April 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ James Cook, A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World, Volume 1.

- ↑ Alcoholic Drinks in New Zealand

- ↑ "Craft beer sales increase by 20 million litres". 3 News NZ. February 26, 2013.

- ↑ NZ Hops website

- ↑ "News | Brewers Guild of New Zealand". Brewersguild.org.nz. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ Jono Galuszka (2011-10-01). "Beer Brewers Hit By Hop Shortage". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ Peter Watson And Fairfax (2012-10-23). "Co-op confident of avoiding hop shortage". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- ↑ winepros.com.au. Oxford Companion to Wine. "New Zealand".

- ↑ "Hawkes Bay Wineries". Jasons Travel Media.

Further reading

- Bollinger, Conrad Grog's Own Country: The Story of Liquor Licensing in New Zealand (Price Milburn Wellington, 1959: 2nd revised edition Minerva Auckland, 1967)

- Connor, J. L.; K. Kypri; M. L. Bell; K. Cousins (September 2010). "Alcohol outlet density, levels of drinking and alcohol-related harm in New Zealand: a national study". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 65 (10): 841. doi:10.1136/jech.2009.104935. ISSN 0143-005X.

- Huckle, Taisia; Megan Pledger; Sally Casswell (2011-12-12). "Increases in Typical Quantities Consumed and Alcohol-Related Problems During a Decade of Liberalizing Alcohol Policy". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 73 (1): 53. PMID 22152662.

External links

- Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand

- Law Commission - "Review of Regulatory Framework for the Sale and Supply of Liquor"

- Alcohol Action NZ, lobby group

- The Demon Drink, Alcohol and Prohibition in New Zealand, Bulletin No 33, 2000 from Hocken Library, Dunedin

- Temperance and Prohibition in New Zealand (1930 history by Murray & Cocker)