Alfonso VI of León and Castile

| Alfonso VI | |

|---|---|

|

Diego Gelmírez and Alfonso VI of León in a miniature from the Codex Calixtinus made in 1145. Located at Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. | |

| Emperor of All Spain | |

| Reign | 1077–1109 |

| Coronation | 1077 |

| Predecessor | Ferdinand I |

| Successor | Urraca & Alfonso |

| King of León | |

| Reign |

1065–1072 1072–1109 |

| Predecessor |

Ferdinand I Sancho II |

| Successor |

Sancho II Urraca |

| King of Castile | |

| Reign | 1072–1109 |

| Predecessor | Sancho II |

| Successor | Urraca |

| King of Galicia and Portugal | |

| Reign |

1071–1072 (jointly with Sancho) 1072–1109 |

| Predecessor |

García II Sancho II |

| Successor |

Sancho II Urraca |

| Born |

1047 Compostela |

| Died |

29 June/1 July 1109 (aged 69) Toledo |

| Burial | Sahagún, León, San Mancio chapel in the royal monastery of Santos Facundo y Primitivo |

| Spouses |

Agnes of Aquitaine Constance of Burgundy 3 more... |

| Issue |

Urraca Sancho Alfónsez Infanta Sancha Elvira, Queen of Sicily Elvira, Countess of Toulouse Theresa, Countess of Portugal |

| House | Jiménez |

| Father | Ferdinand I of León |

| Mother | Sancha of León |

Alfonso VI (1047[1][lower-alpha 1] – 29 June/1 July 1109), nicknamed the Brave (El Bravo) or the Valiant, was the son of Ferdinand I of León and Queen Sancha, daughter of Alfonso V and sister of Bermudo III. He was King of León from 1065, King of Castile and de facto King of Galicia from 1072.[3] After the conquest of Toledo in 1085 he was also the self-proclaimed victoriosissimo rege in Toleto, et in Hispania et Gallecia (most victorious king of Toledo, and of Spain and Galicia).[4]

Division of the kingdom

As the second son of King Ferdinand I and Sancha of León,[5] Alfonso was not meant to inherit the crown. Nevertheless, in 1063, his father convened the royal court to announce his decision to divide the kingdom among his sons: Alfonso was allotted León; Castile was given to his older brother Sancho; and Galicia to his younger brother García.[6] Each of the brothers was also assigned a sphere of influence among the Taifa states. Ferdinand's two daughters each received cities: Elvira that of Toro and Urraca that of Zamora. In giving them these territories, he expressed his desire that they respect his wishes and abide by the split.

Reign

After his father's death in 1065, Alfonso was crowned king of León in January 1066. He had to face the expansionist desires of his brother Sancho who, as the firstborn son, considered himself the legitimate heir of all of his father's kingdoms.[7] The conflict began in 1067 upon the death of Queen Sancha, an event that would lead to a seven-year period of war among the three siblings. Alfonso appears to have taken the first step in violating this division. In 1068 he invaded the Galician client Taifa of Badajoz and extorted tribute. In response, on 19 July 1068, Sancho attacked and defeated Alfonso at Llantada, a trial by ordeal, the outcome of which would be that the brother who was victorious would obtain the kingdom of the one who was defeated. Although Sancho won the combat, Alfonso did not live up to his part.

Despite this, however, both brothers maintained friendly relations as evidenced by the fact that on 26 May 1069, Alfonso was present at the wedding of his brother Sancho where both agreed to join forces to divide among themselves the Kingdom of Galicia which had been allotted to their brother Garcia, the youngest son of King Fernando. Sancho marched across Alfonso's León to conquer García's northern lands at the time that Alfonso was in the southern part of the Galician realm issuing charters. García fled to the taifa of Seville, and the remaining brothers then turned on each other. This conflict culminated in the Battle of Golpejera in early January 1072. Sancho proved victorious and Alfonso was forced to flee to his client Taifa of Toledo.

Later that year as Sancho was mopping up the last of the resistance, besieging his sister Urraca at Zamora in October, he was assassinated. This opened the way for Alfonso to return to claim Sancho's crown. García, induced to return from exile, was imprisoned by Alfonso for life, leaving Alfonso in uncontested control of the reunited territories of their father. In recognition of this and his role as the preeminent Christian monarch on the peninsula, in 1077 Alfonso proclaimed himself "Emperor of all Spain".

In the cantar de gesta Cantar del mio Cid, he plays the part attributed by medieval poets to the greatest kings, and to Charlemagne himself. He is alternately the oppressor and the victim of heroic and self-willed nobles—the idealized types of the patrons for whom the jongleurs and troubadours sang. He is the hero of a cantar de gesta which, like all but a very few of the early Spanish songs, such as the cantar of Bernardo del Carpio and the Infantes of Lara, exists now only in the fragments incorporated in the chronicle of Alfonso the Wise or in ballad form.

His flight from the monastery of Sahagún, where his brother Sancho endeavoured to imprison him, his chivalrous friendship with his host Almamun of Toledo, caballero aunque moro, "a knight although a Moor", the passionate loyalty of his vassal, Pedro Ansúrez, and his brotherly love for his sister Urraca of Zamora, may owe something to the poet who regarded him as a hero.

They are the answer to the poet of the nobles who represented the king as having submitted to taking a degrading oath at the hands of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (El Cid) to deny intervention in his brother's death in the church of Santa Gadea at Burgos, and as having then persecuted the brave man who defied him.

Reputation

Alfonso VI stands out as a strong king whose interest was in law and order. He was a leader of his state during the Reconquista who was regarded by the Arabs as a very fierce and astute enemy, but also as a man who kept his word. A story of Muslim origin tells of how he responded to a challenge during a game of chess made by Muhammad ibn Ammar, the favourite of Al Mutamid, the King of Seville. They played chess on a very beautiful table and with a set of chess pieces belonging to Ibn Ammar. The table and the chess pieces were to go to Alfonso if he won. If Ibn Ammar won, then he could name the stake. The latter did win and demanded that the Christians should spare Seville. Alfonso kept his word.

Whatever truth may lie behind the romantic tales of the relationships and interactions between the Christians and the Muslims during the Reconquista, Alfonso personified the influences that were then shaping the character and civilisation of the Iberian peninsula.

Alfonso showed a greater degree of interest than his predecessors in increasing the links between Iberia and the rest of Christian Europe. The past marital practices of the Iberian royalty had been to limit the choice of partners to the peninsula and Gascony, but Alfonso had French and Italian consorts, and arranged to marry his daughters to French princes and an Italian king. His second marriage was arranged, in part, through the influence of the French Cluniac Order, and Alfonso is said to have introduced them into Iberia, established them in Sahagun and choosing a French Cluniac, Bernard, as the first Archbishop of Toledo after its 1085 conquest. He also drew his kingdom nearer to the Papacy, a move which encouraged French crusaders to aid him in the reconquest of the peninsula from Muslim control, and it was Alfonso's decision which established the Roman ritual in place of the old missal of Saint Isidore—the Mozarabic rite.

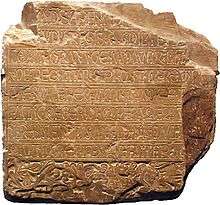

On the other hand, he was tolerant towards the Arabs living in Iberia. He protected the Muslims among his subjects and struck coins with inscriptions in Arabic letters. He also admitted to his court and to his bed the refugee Muslim princess Zaida of Seville.[8]

Marriages and children

Alfonso married at least five times and had two mistresses, one of whom he may later have married.[9][10][11][12] He is also thought to have been betrothed to a daughter of King William I of England, but her name is uncertain.[13]

In 1069, Alfonso married Agnes of Aquitaine, daughter of William VIII of Aquitaine and his second wife Mateoda. They last appear together in May 1077, and then Alfonso appears alone. This suggests that she had died, although Orderic Vitalis reports that in 1109 Alfonso's 'relict' Agnes remarried to Elias I of Maine, leading some to speculate that Alfonso and Agnes had divorced due to consanguinity. It seems more likely that Orderic gave the wrong name to Alfonso's widow, Beatrice. Agnes and Alfonso had no children.

Apparently between his first and second marriages he formed a liaison with Jimena Muñoz, a "most noble" (nobilissima) concubine "derived from royalty" (real generacion). She appears to have been put aside, given land in Ulver, at the time of Alfonso's remarriage. By her Alfonso had two illegitimate daughters, Elvira and Teresa.

His second wife, whom he married by May 1080, was Constance of Burgundy,[14] daughter of Robert I, Duke of Burgundy. This marriage initially faced papal opposition, apparently due to her kinship with Agnes. Her tenure as queen consort brought significant Cluniac influences into the kingdom. She died in September or October, 1093, the mother of Alfonso's eldest legitimate daughter Urraca, and of five other children who died in infancy.

Either before or shortly after Constance's death, Alfonso formed a liaison with a second mistress, Zaida of Seville, said by Iberian Muslim sources to be daughter-in-law of Al Mutamid, the Muslim King of Seville. She fled the fall of Seville for Alfonso's kingdom in 1091, and soon became his lover, having by him Alfonso's only son, Sancho, who, though illegitimate, was apparently not born of an adulterous relationship, and hence born after the death of Constance. He would be named his father's heir. Several modern sources have suggested that Zaida, baptised under the name of Isabel, is identical with Alfonso's later wife, Queen Isabel (or that she was a second queen named Isabel whom he married in succession to the first). Zaida/Isabel died in childbirth, but the date is unknown, and it is unclear whether the child being delivered was Sancho, an additional illegitimate child, otherwise unknown, or legitimate daughter Elvira (if Zaida was identical to Queen Isabel).

By April 1095, Alfonso married Bertha. Chroniclers report her as being from Tuscany, Lombardy, or alternatively, say she was French. Several theories have been put forward regarding her origin. Based on political considerations, proposals make her daughter of William I, Count of Burgundy or of Amadeus II of Savoy. She had no children and died in late 1099 (Alfonso first appears without her in mid-January 1100).

Within months, by May 1100, Alfonso again remarried, to Isabel, having by her two daughters, Sancha, (wife of Rodrigo González de Lara), and Elvira, (who married Roger II of Sicily).[15] A non-contemporary tomb inscription says she was daughter of a "king Louis of France", but this is chronologically impossible. It has been speculated that she was of Burgundian origin, but others conclude that Alfonso married his former mistress, Zaida, who had been baptized as Isabel. (In a novel twist, Reilly suggested that there were two successive queens named Isabel: first the French (Burgundian) Isabel, mother of Sancha and Elvira, with Alfonso only later marrying his mistress Zaida (Isabel), after the death of or divorce from the first Isabel.) Alfonso was again widowed in mid-1107.

By May 1108, Alfonso married his last wife, Beatrice. She, as widow of Alfonso, is said to have returned home to France, but nothing else is known of her origin unless she is the woman Orderic named as "Agnes, daughter of William, Duke of Poitou", who as relict of Alfonso, (Agnetem, filiam Guillelmi, Pictavorum ducis, relictam Hildefonsi senioris, Galliciae regis), remarried to Elias of Maine. If this is the case, she is likely daughter of William IX of Aquitaine and half-sister of Alfonso's first wife, the first Agnes of Aquitaine. Beatrice had no children by Alfonso.

Alfonso was defeated on 23 October 1086, at the battle of Sagrajas, at the hands of Yusuf ibn Tashfin, and Abbad III al-Mu'tamid, and was severely wounded in the leg. However, he recovered to continue as king of Leon and Castile.[16]

Alfonso's designated successor, his son Sancho, was slain after being routed at the Battle of Uclés in 1108, making Alfonso's eldest legitimate daughter, the widowed Urraca as his heir.[17] In order to strengthen her position as his successor, Alfonso began negotiations for her to marry her second cousin, Alfonso I of Aragon and Navarre, but died before the marriage could take place.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Alfonso VI of León and Castile | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

References

- ↑ Martínez Díez 2003, pp. 19,21 and 160.

- ↑ Salazar y Acha 1992–1993, p. 303.

- ↑ "Rege domno Adefonso, qui regebat Castella et Legione et tota Gallecia", Serrano, Luciano (1910). Becerro gótico de Cardeña (PDF). Valladolid: Cuesta. p. 18.

- ↑ Heráldica general y fuentes de las armas de España. (Spanish)

- ↑ Miranda Calvo 1976, p. 112.

- ↑ Martínez Díez 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ Martínez Díez 2003, p. 35.

- ↑ Reilly 1995, p. 92.

- ↑ Canal Sánchez-Pagín 1991, pp. 11–40.

- ↑ Reilly 1988.

- ↑ Salazar y Acha 1992–1993, pp. 299–336.

- ↑ Palencia 1988, pp. 281–90.

- ↑ Douglas 1964, pp. 393–95.

- ↑ Barton 2015, p. 187.

- ↑ Houben 2002, p. 35.

- ↑ Reilly 1995, p. 89.

- ↑ Reilly 1995, p. 97.

Bibliography

- This entry incorporates public domain text originally from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Arco y Garay, Ricardo del (1954). Sepulcros de la Casa Real de Castilla (in Spanish). Madrid: Instituto Jerónimo Zurita. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. OCLC 11366237.

- Barton, Simon (2015). "Spain in the Eleventh Century". In David Luscombe, Jonathan Riley–Smith. The New Cambridge Medieval History. 4, c.1024–c. 1198, Part II. Madrid: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107460638.

- Canal Sánchez-Pagín, José María (1991). "Jimena Muñoz, amiga de Alfonso VI". Anuario de Estudios Medievales (in Spanish). Barcelona: Universidad de Barcelona; Instituto de Historia Medieval de España; CSCIC (21): 11–40. ISSN 0066-5061.

- Carvalho Correia, Francisco (2008). O Mosteiro de Santo Tirso de 978 a 1588: a silhueta de uma entidade projectada no chao de uma história milenária (in Portuguese) (1st ed.). Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela: Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico. ISBN 978-84-9887-038-1.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact upon England. London: Eyre & Spottiswood. OCLC 930444939.

- Elorza, Juan C.; Vaquero, Lourdes; Castillo, Belén; Negro, Marta (1990). Junta de Castilla y León. Consejería de Cultura y Bienestar Social, ed. El Panteón Real de las Huelgas de Burgos. Los enterramientos de los reyes de León y de Castilla. Publisher Evergráficas S.A. ISBN 84-241-9999-5.

- Houben, Hubert (2002). Roger II of Sicily: A Ruler Between East and West. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521652087.

- Luis Corral, Fernando (2012). ""Y sometió a su autoridad todo el reino de los leoneses": formas de ejercicio del poder en la Historia Silense o cómo Alfonso VI llegó al trono". e-Spania. Revue interdisciplinaire d'etudes hispaniques médievales e modernes (in Spanish). Paris: Sorbonne Université (10 (December)). ISSN 1951-6169.

- Martin, George (2010). "Hilando un reino. Alfonso VI y las mujeres". e-Spania. Revue interdisciplinaire d'etudes hispaniques médievales e modernes (http://e-spania.revues.org/20134).

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2003). Alfonso VI: Señor del Cid, conquistador de Toledo (in Spanish). Madrid: Temas de Hoy, S.A. ISBN 84-8460-251-6.

- Mínguez Fernández, José María (2009). "Alfonso VI /Gregorio VII. Soberanía imperial frente a soberanía papal" (PDF). Argutorio: revista de la Asociación Cultural "Monte Irago" (in Spanish) (year 13, number 23). ISSN 1575-801X.

- Miranda Calvo, José (1976). "La Conquista de Toledo por Alfonso VI" (PDF). Toletum: boletín de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo (in Spanish) (7): 101–151. ISSN 0210-6310. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-20.

- Palencia, Clemente (1988). "Historia y leyendas de las mujeres de Alfonso VI". Estudios sobre Alfonso VI y la Reconquista de Toledo (in Spanish). Toledo: Instituto de Estudios Visigótico-Mozárabes de San Eugenio. pp. 281–290. ISBN 8450569826.

- Pallares Méndez, María del Carmen; Portela, Ermelindo (2006). La Reina Urraca (in Spanish). San Sebastián: Nerea, Seria media, 21. ISBN 978-84-96431-18-8.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1995). The Contest of Christian and Muslim Spain. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell. ISBN 9780631199649.

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1989). The Kingdom of León-Castilla under King Alfonso VI, 1065–1109. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1992–1993). "Contribución al reinado de Alfonso VI de Castilla: algunas aclaraciones sobre su política matrimonial". Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía. II. ISSN 1133-1240.

Further reading

- Solsten, Eric; Keefe, Eugene K. (1993). Luis R. Mortimer, ed. Portugal: a Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 9780844407760.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfonso VI of León and Castile. |

| Alfonso VI of León and Castile Born: before June 1040 Died: June 29/1 July 1109 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ferdinand I |

King of León 1065–1072 |

Succeeded by Sancho II |

| Preceded by García II |

King of Galicia 1071–1072 with Sancho II | |

| Preceded by Sancho II |

King of León, Castile and Galicia 1072–1109 |

Succeeded by Urraca |

| Preceded by Al-Qadir |

King of Toledo 1085–1109 | |

| Vacant Title last held by Ferdinand I |

Emperor of Spain 1077–1109 |

Succeeded by Urraca and Alfonso |

%2C_15th_Century.svg.png)

.svg.png)