Kingdom of Castile

| Kingdom of Castile | ||||||||||||

| Reino de Castilla (Spanish) Regnum Castellae (Latin) | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Capital | No settled capital[n. 1] | |||||||||||

| Languages | Castilian, Basque, Mozarabic, Andalusian Arabic | |||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic majority | |||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | |||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||

| • | 1065–1072 | Sancho II (first) | ||||||||||

| • | 1217–1230 | Ferdinand III (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||||

| • | Established | 1065 | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1230 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||

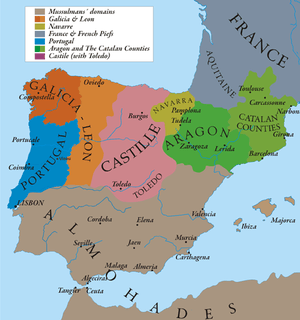

The Kingdom of Castile (/kæˈstiːl/; Spanish: Reino de Castilla, Latin: Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began as the County of Castile (Condado de Castilla), an eastern frontier lordship of the Kingdom of León in the 9th century. During the 10th century its counts increased their autonomy, but it was not until 1065 that it was separated from León and became a kingdom in its own right. Between 1072 and 1157 it was again united with León, and after 1230 this union became permanent. Throughout this period the Castilian kings made extensive conquests in the southern Iberia at the expense of the Islamic principalities. Castile and León, with their southern acquisitions, came to be known collectively as the Crown of Castile, a term that also came to encompass overseas expansion.

History

9th to 11th centuries: The beginnings

According to the chronicles of Alfonso III of Asturias; the first reference to the name "Castile" (Castilla) can be found in a document written during AD 800. In Al-Andalus chronicles from the Cordoban Caliphate, the oldest sources refer to it as Al-Qila, or "the castled" high plains past the territory of Alava, more south to it and the first encountered in their expeditions from Zaragoza. The name reflects its origin as a march on the eastern frontier of the Kingdom of Asturias, protected by castles, towers or castra.

The County of Castile, bordered in the south by the Montes de Toledo, was re-populated by inhabitants of Cantabria, Asturias, Vasconia and Visigothic and Mozarab origins. It had its own Romance dialect and customary laws.

From the first half of the 9th century until the middle of the century, in which it came to be paid more closer attention to, its administration and defense by the monarchs of Leon - due the increased incursions from the Emirate of Córdoba - its first repopulation settlements were led by small abbots and local counts from the other side of the Cantabrian ridge neighbor valleys, Trasmiera and Primorias and smaller ones, being its first settlers from the contiguous maritime valleys of Mena and Encartaciones in nearby Biscay, some of whom had abandoned those exposed areas of the Meseta a few decades earlier, and taken refuge by the much dense and intractable woods of the Atlantic valleys, so they were not that foreign to them.

A mix of settlers from the recently swelled with refugees Cantabrian and Basque coastal areas, were led under the protection of Abbot Vitulus and his brother, count Herwig, as registered in the local charters they signed around the first years of the 800's. The areas that they settled didn't extend far from the Cantabrian southeastern ridges, and not beyond the southern reaches of the high Ebro river valleys and canyon gores.

The first Count of a wider and more united Castile was Rodrigo in 850, under Ordoño I of Asturias and Alfonso III of Asturias, who settled and fortified the ancient Cantabrian hill town of Amaya, much farther west and south of the Ebro river to offer a more easy defense and command of the still functional Roman Empire main highway passing by, south of the Cantabrian ridge all the way to Leon, from the Muslim military expeditions. Subsequently, the region was subdivided, separate counts being named to Alava, Burgos, Cerezo & Lantarón, and a reduced Castile. In 931 the County was reunified by Count Fernán González, who rose in rebellion against the Kingdom of León, successor state to Asturias, and achieved an autonomous status, allowing the county to be inherited by his family instead of being subject to appointment by the Leonese king.

11th and 12th centuries: Expansion and union with the Kingdom of León

The minority of Count García Sánchez led Castile to accept Sancho III of Navarre, married to the sister of Count García, as feudal overlord. García was assassinated in 1028 while in León to marry the princess Sancha, sister of Bermudo III of León. Sancho III, acting as feudal overlord, appointed his younger son (García's nephew) Ferdinand as Count of Castile, marrying him to his uncle's intended bride, Sancha of León. Following Sancho's 1035 death, Castile returned to the nominal control of León, but Ferdinand, allying himself with his brother García Sánchez III of Navarre, began a war with his brother-in-law Bermudo. At the Battle of Tamarón Bermudo was killed, leaving no surviving offspring.[2] In right of his wife, Ferdinand then assumed the royal title as king of León and Castile, for the first time associating the royal title with the rule of Castile.[3]

When Ferdinand I died in 1065, the territories were divided among his children. Sancho II became King of Castile,[4] Alfonso VI, King of León and García, King of Galicia,[5] while his daughters were given towns, Urraca, Zamora, and Elvira, Toro.

Sancho II allied himself with Alfonso VI of León and together they conquered, then divided Galicia. Sancho later attacked Alfonso VI and invaded León with the help of El Cid, and drove his brother into exile, thereby reuniting the three kingdoms. Urraca permitted the greater part of the Leonese army to take refuge in the town of Zamora. Sancho laid siege to the town, but the Castilian king was assassinated in 1072 by Bellido Dolfos, a Galician nobleman. The Castilian troops then withdrew.

As a result, Alfonso VI recovered all his original territory of León, and now also became the king of Castile and Galicia. This was the second union of León and Castile, although the two kingdoms remained distinct entities joined only in a personal union. The sworn oath taken by El Cid before Alfonso VI in Santa Gadea de Burgos regarding the innocence of Alfonso in the matter of the murder of his brother is well known.

Under Alfonso VI, there was an approach to the rest of Europeans kingdoms, including France. He gave his daughters, Elvira, Urraca and Theresa, in marriage to Raymond of Toulouse, Raymond of Burgundy and Henry of Burgundy respectively. In the Council of Burgos in 1080 the traditional Mozarabic rite was replaced by the Roman one. Upon his death, Alfonso VI was succeeded by his daughter the widowed Urraca, who then married Alfonso I of Aragon, but they almost immediately fell out, and Alfonso tried unsuccessfully to conquer Urraca's lands, before he repudiated her in 1114. Urraca also had to contend with attempts by her son (offspring of her first marriage), the king of Galicia, to assert his rights. When Urraca died, this son became king of León and Castile as Alfonso VII. During his reign, Alfonso VII managed to annex parts of the weaker kingdoms of Navarre and Aragón which fought to secede after the death of Alfonso I of Aragon. Alfonso VII refused his right to conquer the Mediterranean coast for the new union of Aragón with the County of Barcelona (Petronila and Ramón Berenguer IV).

12th century: A link between Christianity and Islam

The centuries of Moorish rule had confirmed the high central tableland of Castile as a vast sheep pasturage; the fact that the greater part of Spanish sheep-rearing terminology was drawn from Arabic underscores the debt.[6]

The 8th and 9th centuries was preceded by a period of Umayyad conquests, as Arabs took control of previously Hellenized areas such as Egypt and Syria in the 7th century.[7] At this point they first began to encounter Greek ideas, though from the beginning, many Arabs were hostile to classical learning.[8] Because of this hostility, the religious Caliphs could not support scientific translations. Translators had to seek out wealthy business patrons rather than religious ones.[8] Until Abassid rule in the 8th century, however, there was little work in translation. Most knowledge of Greek during Umayyad rule was gained from those scholars of Greek who remained from the Byzantine period, rather than through widespread translation and dissemination of texts. A few scholars argue that translation was more widespread than is thought during this period, but theirs remains the minority view.[8]

The main period of translation was during Abbasid rule. The 2nd Abassid Caliph Al-Mansur moved the capital from Damascus to Baghdad.[9] Here he founded the great library with texts containing Greek Classical texts. Al-Mansur ordered this rich fund of world literature translated into Arabic. Under al-Mansur and by his orders, translations were made from Greek, Syriac, and Persian, the Syriac and Persian books being themselves translations from Greek or Sanskrit.[10]

Owing to the legacy of the 6th century King of Persia, Anushirvan (Chosroes I) the Just had introducing many Greek ideas into his kingdom.[11] Aided by this knowledge and juxtaposition of beliefs, the Abassids considered it valuable to look at Islam with Greek eyes, and to look at the Greeks with Islamic eyes.[8] Abassid philosophers also pressed the idea that Islam had from the very beginning stressed the gathering of knowledge as important to the religion. These new lines of thought allowed the work of amassing and translating Greek ideas to expand as it never before had.[12]

During the 12th century, Europe enjoyed a great advance in intellectual achievements sparked in part by the kingdom of Castile's conquest of the great cultural center of Toledo (1085). There Arabic classics were discovered, and contacts established with the knowledge and works of Muslim scientists. In the first half of the century a program of translations, traditionally called the "School of Toledo", was undertaken which rendered many philosophical and scientific works from the classical Greek and the Islamic worlds into Latin. Many European scholars, including Daniel of Morley and Gerard of Cremona travelled to Toledo to gain further education.

The Way of St. James further enhanced the cultural exchange between the kingdoms of Castile and León and the rest of Europe.

The 12th century saw the establishment of many new religious orders, after the European fashion, such as Calatrava, Alcántara and Santiago; and the foundation of many Cistercian abbeys.

Castile and León

13th century: Definitive union with the Kingdom of León

Alfonso VII restored the royal tradition of dividing his kingdom among his children. Sancho III became King of Castile and Ferdinand II, King of León.

The rivalry between both kingdoms continued until 1230 when Ferdinand III of Castile received the Kingdom of León from his father Alfonso IX, having previously received the Kingdom of Castile from his mother Berenguela of Castile in 1217. In addition, he took advantage of the decline of the Almohad empire to conquer the Guadalquivir Valley whilst his son Alfonso X took the taifa of Murcia.

The Courts from León and Castile merged, an event considered as the foundation of the Crown of Castile, consisting of the kingdoms of Castile, León, taifas and other domains conquered from the Moors, including the taifa of Córdoba, taifa of Murcia, taifa of Jaén and taifa of Seville.

14th and 15th centuries: The House of Trastámara

The House of Trastámara was a lineage that ruled Castile from 1369 to 1504, Aragón from 1412 to 1516, Navarre from 1425 to 1479, and Naples from 1442 to 1501.

Its name was taken from the Count (or Duke) of Trastámara.[13] This title was used by Henry II of Castile, of the Mercedes, before coming to the throne in 1369, during the civil war with his legitimate brother, King Peter of Castile. John II of Aragón ruled from 1458 to 1479 and upon his death, his daughter became Queen Eleanor of Navarre and his son became King Ferdinand II of Aragon.

Union of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon

The marriage of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, in 1469 at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid, began a familial union of the two kingdoms. They became known as the Catholic Monarchs (los Reyes Católicos). Isabella succeeded her brother as Queen of Castile and Ferdinand became jure uxoris King of Castile in 1474. When Ferdinand succeeded his father as King of Aragon in 1479, the Crown of Castile and the various territories of the Crown of Aragon were united in a personal union creating for the first time since the 8th century a single political unit referred to as España (Spain). 'Los Reyes Católicos' started policies to diminish the power of the bourgeoisie and nobility in Castile, and greatly reduced the powers of the Cortes (General Courts) to the point where they ' rubber-stamped ' the monarch's acts, and brought the nobility to their side. In 1492 the Kingdom of Castile conquered the last Moorish state of Granada, thereby ending Muslim rule in Iberia and completing the Reconquista.

16th century

On Isabella's death in 1504 her daughter, Joanna I, became Queen (in name) with her husband Philip I as King (in authority). After his death Joanna's father was regent, due to her perceived mental illness, as her son Charles I was only six years old. On Ferdinand II's death in 1516, Charles I was proclaimed as king of Castile and of Aragon (in authority) jointly with his mother Joanna I as the Queen of Aragon (in name).[14] As the first royal to reign over both Castile and Aragon he may be considered as the first operational King of Spain. Charles I also became Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1519.

Government: Municipal councils and parliaments

As with all medieval kingdoms, supreme power was understood to reside in the monarch "by the grace of God", as the legal formula explained. Nevertheless, rural and urban communities began to form assemblies to issue regulations to deal with everyday problems. Over time, these assemblies evolved into municipal councils, known as variously as ayuntamientos or cabildos, in which some of the inhabitants, the property-owning heads of households (vecinos), represented the rest. By the 14th century these councils had gained more powers, such as the right to elect municipal magistrates and officers (alcaldes, speakers, clerks, etc.) and representatives to the parliaments (Cortes).

Due to the increasing power of the municipal councils and the need for communication between these and the King, cortes were established in the Kingdom of León in 1188, and in Castile in 1250. In the earliest Leonese and Castilian Cortes, the inhabitants of the cities (known as "laboratores") formed a small group of the representatives and had no legislative powers, but they were a link between the king and the general population, something that was pioneered by the kingdoms of Castile and León. Eventually the representatives of the cities gained the right to vote in the Cortes, often allying with the monarchs against the great noble lords.

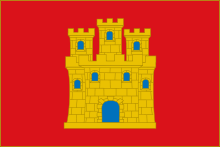

Arms of the Kingdom of Castile

During the reign of Alfonso VIII, the kingdom began to use as its emblem, both in blazons and banners, the canting arms of the Kingdom of Castile: gules, a three towered castle or, masoned sable and ajouré azure.

-

.svg.png)

Coat of arms of Castile

-

Coat of arms of Castile with the Royal Crest

See also

- Al Andalus

- Crown of Castile

- Council of Castile

- History of Spain

- List of Castilian counts

- List of Castilian monarchs

- List of Castilian battles

Notes

- ↑ Burgos, Valladolid and Toledo were centres of royal authority of the Kingdom and the later Crown of Castile.[1]

References

- ↑ Guillén, Fernando Arias. (2013). "A kingdom without a capital? Itineration and spaces of royal power in Castile, c.1252–1350". Journal of Medieval History, Vol. 39(4).

- ↑ Bernard F. Reilly, The Contest of Christian and Muslim Spain, (Blackwell Publishers, 1995), 27.

- ↑ Bernard F. Reilly, 27.

- ↑ Bernard F. Reilly, 39.

- ↑ Bernard F. Reilly, 39

- ↑ H.C. Darby, "The face of Europe on the eve of the great discoveries", in The New Cambridge Modern History vol. I, 1957:23.

- ↑ Rosenthal 2

- 1 2 3 4 Rosenthal 3-4

- ↑ Lindberg 55

- ↑ O'Leary 1922, p. 107.

- ↑ Brickman 84-85

- ↑ Rosenthal 5

- ↑ Ruiz, Teofilo F. (2007). Spain's Centuries of Crisis: 1300-1474. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4051-2789-9.

- ↑ Estudio documental de la Moneda Castilian de Carlos I fabricada en los Países Bajos (1517); José María de Francisco Olmos, pp. 139-140

External links

- The Kingdom of Castile (1157-1212) : Towards a Geography of the Southern Frontier

- History of the County of Castile - The origins of Castile

.svg.png)