Allosteric regulation

In biochemistry, allosteric regulation (or allosteric control) is the regulation of an enzyme by binding an effector molecule at a site other than the enzyme's active site.

The site to which the effector binds is termed the allosteric site. Allosteric sites allow effectors to bind to the protein, often resulting in a conformational change involving protein dynamics. Effectors that enhance the protein's activity are referred to as allosteric activators, whereas those that decrease the protein's activity are called allosteric inhibitors.

Allosteric regulations are a natural example of control loops, such as feedback from downstream products or feedforward from upstream substrates. Long-range allostery is especially important in cell signaling.[1] Allosteric regulation is also particularly important in the cell's ability to adjust enzyme activity.

The term allostery comes from the Greek allos (ἄλλος), "other," and stereos (στερεὀς), "solid (object)." This is in reference to the fact that the regulatory site of an allosteric protein is physically distinct from its active site.

Models of allosteric regulation

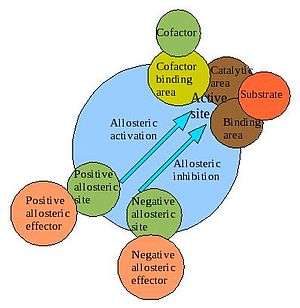

B - Allosteric site

C - Substrate

D - Inhibitor

E - Enzyme

This is a diagram of allosteric regulation of an enzyme.

Most allosteric effects can be explained by the concerted MWC model put forth by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux,[2] or by the sequential model described by Koshland, Nemethy, and Filmer.[3] Both postulate that enzyme subunits exist in one of two conformations, tensed (T) or relaxed (R), and that relaxed subunits bind substrate more readily than those in the tense state. The two models differ most in their assumptions about subunit interaction and the preexistence of both states.

Concerted model

The concerted model of allostery, also referred to as the symmetry model or MWC model, postulates that enzyme subunits are connected in such a way that a conformational change in one subunit is necessarily conferred to all other subunits. Thus, all subunits must exist in the same conformation. The model further holds that, in the absence of any ligand (substrate or otherwise), the equilibrium favors one of the conformational states, T or R. The equilibrium can be shifted to the R or T state through the binding of one ligand (the allosteric effector or ligand) to a site that is different from the active site (the allosteric site).

Sequential model

The sequential model of allosteric regulation holds that subunits are not connected in such a way that a conformational change in one induces a similar change in the others. Thus, all enzyme subunits do not necessitate the same conformation. Moreover, the sequential model dictates that molecules of a substrate bind via an induced fit protocol. In general, when a subunit randomly collides with a molecule of substrate, the active site, in essence, forms a glove around its substrate. While such an induced fit converts a subunit from the tensed state to relaxed state, it does not propagate the conformational change to adjacent subunits. Instead, substrate-binding at one subunit only slightly alters the structure of other subunits so that their binding sites are more receptive to substrate. To summarize:

- subunits need not exist in the same conformation

- molecules of substrate bind via induced-fit protocol

- conformational changes are not propagated to all subunits

Morpheein model

The morpheein model of allosteric regulation is a dissociative concerted model.[4]

A morpheein is a homo-oligomeric structure that can exist as an ensemble of physiologically significant and functionally different alternate quaternary assemblies. Transitions between alternate morpheein assemblies involve oligomer dissociation, conformational change in the dissociated state, and reassembly to a different oligomer. The required oligomer disassembly step differentiates the morpheein model for allosteric regulation from the classic MWC and KNF models. Porphobilinogen synthase (PBGS) is the prototype morpheein.

Allosteric resources online

Allosteric database

Allostery is a direct and efficient means for regulation of biological macromolecule function, produced by the binding of a ligand at an allosteric site topographically distinct from the orthosteric site. Due to the often high receptor selectivity and lower target-based toxicity, allosteric regulation is also expected to play an increasing role in drug discovery and bioengineering. The AlloSteric Database (ASD, http://mdl.shsmu.edu.cn/ASD)[5] provides a central resource for the display, search and analysis of the structure, function and related annotation for allosteric molecules. Currently, ASD contains allosteric proteins from more than 100 species and modulators in three categories (activators, inhibitors, and regulators). Each protein is annotated with detailed description of allostery, biological process and related diseases, and each modulator with binding affinity, physicochemical properties and therapeutic area. Integrating the information of allosteric proteins in ASD should allow the prediction of allostery for unknown proteins, to be followed with experimental validation. In addition, modulators curated in ASD can be used to investigate potential allosteric targets for a query compound, and can help chemists to implement structure modifications for novel allosteric drug design.

Allosteric residues & their prediction using the STRESS web server

Not all protein residues play equally important roles in allosteric regulation. The identification of residues that are essential to allostery (so-called “allosteric residues”) has been the focus of many studies, especially within the last decade.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] In part, this growing interest is a result of their general importance in protein science, but also because allosteric residues may be exploited in biomedical contexts. Pharmacologically important proteins with difficult-to-target sites may yield to approaches in which one alternatively targets easier-to-reach residues that are capable of allosterically regulating the primary site of interest. These residues can broadly be classified as surface- and interior-allosteric amino acids. Allosteric sites at the surface generally play regulatory roles that are fundamentally distinct from those within the interior; surface residues may serve as receptors or effector sites in allosteric signal transmission, whereas those within the interior may act to transmit such signals. STRucturally-identified ESSential residues (STRESS, http://stress.molmovdb.org) is a web tool that enables users to submit their own protein structures of interest in order to predict both surface- and interior-allosteric residues in an algorithmically efficient manner.[14] The software behind this server employs 3D structures to build models of conformational change in order to perform predictions.

Allosteric modulation

Positive modulation

Positive allosteric modulation (also known as allosteric activation) occurs when the binding of one ligand enhances the attraction between substrate molecules and other binding sites. An example is the binding of oxygen molecules to hemoglobin, where oxygen is effectively both the substrate and the effector. The allosteric, or "other", site is the active site of an adjoining protein subunit. The binding of oxygen to one subunit induces a conformational change in that subunit that interacts with the remaining active sites to enhance their oxygen affinity. Another example of allosteric activation is seen in cytosolic IMP-GMP specific 5'-nucleotidase II (cN-II), where the affinity for substrate GMP increases upon GTP binding at the dimer interface[15]

Negative modulation

Negative allosteric modulation (also known as allosteric inhibition) occurs when the binding of one ligand decreases the affinity for substrate at other active sites. For example, when 2,3-BPG binds to an allosteric site on hemoglobin, the affinity for oxygen of all subunits decreases. This is when a regulator is absent from the binding site.

Direct thrombin inhibitors provides an excellent example of negative allosteric modulation. Allosteric inhibitors of thrombin have been discovered which could potentially be used as anticoagulants.

Another example is strychnine, a convulsant poison, which acts as an allosteric inhibitor of the glycine receptor. Glycine is a major post-synaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter in mammalian spinal cord and brain stem. Strychnine acts at a separate binding site on the glycine receptor in an allosteric manner; i.e., its binding lowers the affinity of the glycine receptor for glycine. Thus, strychnine inhibits the action of an inhibitory transmitter, leading to convulsions.

Another instance in which negative allosteric modulation can be seen is between ATP and the enzyme Phosphofructokinase within the negative feedback loop that regulates glycolysis. Phosphofructokinase (generally referred to as PFK) is an enzyme that catalyses the third step of glycolysis: the phosphorylation of Fructose-6-phosphate into Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. PFK can be allosterically inhibited by high levels of ATP within the cell. When ATP levels are high, ATP will bind to an allosteoric site on phosphofructokinase, causing a change in the enzyme's three-dimensional shape. This change causes its affinity for substrate (fructose-6-phosphate and ATP) at the active site to decrease, and the enzyme is deemed inactive. This causes glycolysis to cease when ATP levels are high, thus conserving the body's glucose and maintaining balanced levels of cellular ATP. In this way, ATP serves as a negative allosteric modulator for PFK, despite the fact that it is also a substrate of the enzyme.

Types of allosteric regulation

Homotropic

A homotropic allosteric modulator is a substrate for its target enzyme, as well as a regulatory molecule of the enzyme's activity. It is typically an activator of the enzyme. For example, O2 and CO are homotropic allosteric modulators of hemoglobin.

Heterotropic

A heterotropic allosteric modulator is a regulatory molecule that is not the enzyme's substrate. It may be either an activator or an inhibitor of the enzyme. For example, H+, CO2, and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate are heterotropic allosteric modulators of hemoglobin.[16]

Some allosteric proteins can be regulated by both their substrates and other molecules. Such proteins are capable of both homotropic and heterotropic interactions.

Non-regulatory allostery

A non-regulatory allosteric site refers to any non-regulatory component of an enzyme (or any protein), that is not itself an amino acid. For instance, many enzymes require sodium binding to ensure proper function. However, the sodium does not necessarily act as a regulatory subunit; the sodium is always present and there are no known biological processes to add/remove sodium to regulate enzyme activity. Non-regulatory allostery could comprise any other ions besides sodium (calcium, magnesium, zinc), as well as other chemicals and possibly vitamins.

Pharmacology

Allosteric modulation of a receptor results from the binding of allosteric modulators at a different site (a "regulatory site") from that of the endogenous ligand (an "active site") and enhances or inhibits the effects of the endogenous ligand. Under normal circumstances, it acts by causing a conformational change in a receptor molecule, which results in a change in the binding affinity of the ligand. In this way, an allosteric ligand modulates the receptor's activation by its primary (orthosteric) ligand, and can be thought to act like a dimmer switch in an electrical circuit, adjusting the intensity of the response.

For example, the GABAA receptor has two active sites that the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binds, but also has benzodiazepine and general anaesthetic agent regulatory binding sites. These regulatory sites can each produce positive allosteric modulation, potentiating the activity of GABA. Diazepam is an agonist at the benzodiazepine regulatory site, and its antidote flumazenil is an antagonist.

More recent examples of drugs that allosterically modulate their targets include the calcium-mimicking cinacalcet and the HIV treatment maraviroc.

Allosteric sites as drug targets

Allosteric sites may represent a novel drug target. There are a number of advantages in using allosteric modulators as preferred therapeutic agents over classic orthosteric ligands. For example, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) allosteric binding sites have not faced the same evolutionary pressure as orthosteric sites to accommodate an endogenous ligand, so are more diverse.[17] Therefore, greater GPCR selectivity may be obtained by targeting allosteric sites.[17] This is particularly useful for GPCRs where selective orthosteric therapy has been difficult because of sequence conservation of the orthosteric site across receptor subtypes.[18] Also, these modulators have a decreased potential for toxic effects, since modulators with limited co-operativity will have a ceiling level to their effect, irrespective of the administered dose.[17] Another type of pharmacological selectivity that is unique to allosteric modulators is based on co-operativity. An allosteric modulator may display neutral co-operativity with an orthosteric ligand at all subtypes of a given receptor except the subtype of interest, which is termed "absolute subtype selectivity".[18] If an allosteric modulator does not possess appreciable efficacy, it can provide another powerful therapeutic advantage over orthosteric ligands, namely the ability to selectively tune up or down tissue responses only when the endogenous agonist is present.[18] Oligomer-specific small molecule binding sites are drug targets for medically relevant morpheeins.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Bu Z, Callaway DJ (2011). "Proteins MOVE! Protein dynamics and long-range allostery in cell signaling". Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. 83: 163–221. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381262-9.00005-7. ISBN 9780123812629. PMID 21570668.

- ↑ J. Monod, J. Wyman, J.P. Changeux. (1965). On the nature of allosteric transitions:A plausible model. J. Mol. Biol., May;12:88-118.

- ↑ D.E. Jr Koshland, G. Némethy, D. Filmer (1966) Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry. Jan;5(1):365-8

- ↑ E. K. Jaffe (2005). "Morpheeins - a new structural paradigm for allosteric regulation". Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 (9): 490–497. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.003. PMID 16023348.

- ↑ Huang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Cao, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, X.; et al. (2011). "ASD: a comprehensive database of allosteric proteins and modulators". Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D663–669. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1022.

- ↑ Panjkovich, Alejandro; Daura, Xavier (2012-01-01). "Exploiting protein flexibility to predict the location of allosteric sites". BMC Bioinformatics. 13: 273. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-13-273. ISSN 1471-2105. PMC 3562710

. PMID 23095452.

. PMID 23095452. - ↑ Süel, Gürol M.; Lockless, Steve W.; Wall, Mark A.; Ranganathan, Rama (2003-01-01). "Evolutionarily conserved networks of residues mediate allosteric communication in proteins". Nature Structural Biology. 10 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1038/nsb881. ISSN 1072-8368. PMID 12483203.

- ↑ Mitternacht, Simon; Berezovsky, Igor N. (2011-09-01). "Binding leverage as a molecular basis for allosteric regulation". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (9): e1002148. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002148. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 3174156

. PMID 21935347.

. PMID 21935347. - ↑ Gasper, Paul M.; Fuglestad, Brian; Komives, Elizabeth A.; Markwick, Phineus R. L.; McCammon, J. Andrew (2012-12-26). "Allosteric networks in thrombin distinguish procoagulant vs. anticoagulant activities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (52): 21216–21222. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218414109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3535651

. PMID 23197839.

. PMID 23197839. - ↑ Ghosh, Amit; Vishveshwara, Saraswathi (2008-11-04). "Variations in clique and community patterns in protein structures during allosteric communication: investigation of dynamically equilibrated structures of methionyl tRNA synthetase complexes". Biochemistry. 47 (44): 11398–11407. doi:10.1021/bi8007559. ISSN 1520-4995. PMID 18842003.

- ↑ Sethi, Anurag; Eargle, John; Black, Alexis A.; Luthey-Schulten, Zaida (2009-04-21). "Dynamical networks in tRNA:protein complexes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (16): 6620–6625. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810961106. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2672494

. PMID 19351898.

. PMID 19351898. - ↑ Vanwart, Adam T.; Eargle, John; Luthey-Schulten, Zaida; Amaro, Rommie E. (2012-08-14). "Exploring residue component contributions to dynamical network models of allostery". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 8 (8): 2949–2961. doi:10.1021/ct300377a. ISSN 1549-9626. PMC 3489502

. PMID 23139645.

. PMID 23139645. - ↑ Rivalta, Ivan; Sultan, Mohammad M.; Lee, Ning-Shiuan; Manley, Gregory A.; Loria, J. Patrick; Batista, Victor S. (2012-05-29). "Allosteric pathways in imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (22): E1428–1436. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120536109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3365145

. PMID 22586084.

. PMID 22586084. - ↑ Clarke, Declan; Sethi, Anurag; Li, Shantao; Kumar, Sushant; Chang, Richard W. F.; Chen, Jieming; Gerstein, Mark (2016-04-02). "Identifying Allosteric Hotspots with Dynamics: Application to Inter- and Intra-species Conservation". Structure (London, England: 1993). 24: 826–37. doi:10.1016/j.str.2016.03.008. ISSN 1878-4186. PMID 27066750.

- ↑ Srinivasan B; et al. (2014). "Allosteric regulation and substrate activation in cytosolic nucleotidase II from Legionella pneumophila.". FEBS J. 281 (6): 1613–1628. doi:10.1111/febs.12727. PMC 3982195

. PMID 24456211.

. PMID 24456211. - ↑ Edelstein, SJ (1975). "Cooperative interactions of hemoglobin". Annu Rev Biochem. 44: 209–232. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.001233. PMID 237460.

- 1 2 3 A. Christopoulos, L.T. May, V.A. Avlani and P.M. Sexton (2004) G protein-coupled receptor allosterism:the promise and the problem(s). Biochemical Society Transactions Volume 32, part 5

- 1 2 3 May, L.T.; Leach, K.; Sexton, P.M.; Christopoulos, A. (2007). "Allosteric Modulation of G Protein–Coupled Receptors". Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47: 1–51. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105159. PMID 17009927.

- ↑ E. K. Jaffe (2010). "Morpheeins - A new pathway for allosteric drug discovery". Open Conf. Proc. J. 1: 1–6. doi:10.2174/2210289201001010001. PMC 3107518

. PMID 21643557.

. PMID 21643557.

External links

- Instant insight introducing a classification system for protein allostery mechanisms from the Royal Society of Chemistry