Zine

A zine (/ˈziːn/ ZEEN; short for magazine or fanzine) is most commonly a small-circulation self-published work of original or appropriated texts and images, usually reproduced via photocopier. Usually zines are the product of a single person, or a very small group. Zines first emerged in the United States, where the photocopier was invented, and have always been more numerous there.

Popularly defined as having a circulation of 1,000 or fewer copies, in practice many zines are produced in editions of fewer than 100. The primary intent of publication is to advance the views of the editor rather than profit, since the time and materials necessary to create a zine are seldom matched by revenue from its sale. Zines have served as a significant medium of communication in various subcultures, and frequently draw inspiration from a "do-it-yourself" philosophy.

Zines are written in a variety of formats, from desktop-published text to comics to handwritten text (an example being the hardcore punk zine Cometbus). Print remains the most popular zine format, usually photocopied with a small circulation. Topics covered are broad, including fanfiction, politics, poetry, art and design, ephemera, personal journals, social theory, riot grrrl and intersectional feminism, single-topic obsession, or sexual content far outside of the mainstream enough to be prohibitive of inclusion in more traditional media. (An example of the latter is Boyd McDonald's Straight to Hell, which reached a circulation of 20,000.[1])

In recent years a number of photocopied zines have risen to prominence or professional status and have found wide bookstore and online distribution. Notable among these are Giant Robot, Dazed & Confused, Bust, Bitch, Cometbus, Doris, Brainscan, The Miscreant, and Maximum RocknRoll.

History

Overview and origins

The word zine is short for magazine or fanzine, and refers to "self-publications, motivated by a desire for self-expression, not for profit", according to the Barnard Zine Library.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary defines zine exclusively as a shortened form of fanzine.[3]

Dissidents and members of socially marginalized groups have published their own opinions in leaflet and pamphlet form for as long as such technology has been available. NYU professor Stephen Duncombe, Factsheet Five, and others trace the lineage from as far back as Thomas Paine's exceptionally popular 1775 pamphlet Common Sense and other 18th century political pamphlets.[4]

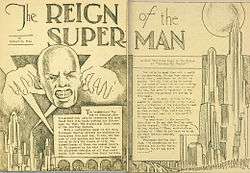

In the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin also started a literary magazine for psychiatric patients at a Pennsylvania hospital, which was distributed among the patients and hospital staff. This could be considered the first zine, since it captures the essence of the philosophy and meaning of zines.[5] The concept of zines had an ancestor in the amateur press movement of the late 19th and early 20th century, which would in its turn cross-pollinate with the subculture of science fiction fandom in the 1930s. Author H. P. Lovecraft had a major preoccupation with the amateur press movement.

1930s–1960s and science fiction

During and after the Great Depression, editors of "pulp" science fiction magazines became increasingly frustrated with letters detailing the impossibilities of their science fiction stories. Over time they began to publish these overly-scrutinizing letters, complete with their return addresses. This allowed these fans to begin writing to each other, now complete with a mailing list for their own science fiction fanzines.[6]

Fanzines enabled fans to write not only about science fiction but about fandom itself and, in self-proclaimed perzines (i.e. personal zine), about themselves. The Damien Broderick novel Transmitters (1984) illustrates how, unlike the typically isolated self-publisher, the more "fannish" (fandom-oriented) fanzine publishers had shared sensibilities and close-knit communities. The relationships between fans were as important as the literature that inspired them.

A number of leading science fiction and fantasy authors rose through the ranks of fandom, such as Frederik Pohl and Isaac Asimov. George R. R. Martin is also said to have started writing for fanzines, but has been quoted condemning the practice of fans writing stories set in other authors' worlds.

1970s and punk

Punk zines emerged as part of the punk subculture in the late 1970s. These started in the UK and the U.S.A. and by March 1977 had spread to other countries such as Ireland.[7] Cheap photocopying had made it easier than ever for anyone who could make a band flyer to make a zine.

1980s and Factsheet Five

During the 1980s and onwards, Factsheet Five (the name came from a short story by John Brunner), originally published by Mike Gunderloy and now defunct, catalogued and reviewed any zine or small press creation sent to it, along with their mailing addresses. In doing so, it formed a networking point for zine creators and readers (usually the same people). The concept of zine as an art form distinct from fanzine, and of the "zinesters" as member of their own subculture, had emerged. Zines of this era ranged from perzines of all varieties to those that covered an assortment of different and obscure topics that web sites (such as Wikipedia) might cover today but for which no large audience existed in the pre-internet era.

1990s and riot grrrl/girl zines

The zine subgenre of "girl zines" originates with the riot grrrl movement, and both are associated with third-wave feminism.[8]:2, 4, 9, 18 As feminist documents, these zines emerge from a longer legacy of feminist and/or women's self-publication that includes scrapbooking as well as the creation of women's health literature and a variety of mimeographed pamphlets. For women writing all of these documents, self-publishing allowed them to circulate ideas that would not otherwise be published.[8]:29 As traditional press coverage of riot grrrl zines and music was "superficial, at best, and damagingly counter-productive, at worst," zinesters Erika Rienstien and May Summer founded the Riot Grrrl Press to serve as a zine distribution network that would allow riot grrrls to "express themselves and reach large audiences without having to rely on the mainstream press".[9] Zine scholars Kevin Dunn and May Summer Farnsworth use this excerpt of Erika Reinstein's Fantastic Fanzine no. 2 to explain the relationship between politics and media production for girl zinesters:[10]

"BECAUSE we girls want to create mediums that speak to US. We are tired of boy band after boy band, boy zine after boy zine, boy punk after boy punk after boy . . ."BECAUSE in every form of media I see us/myself slapped, decapitated, laughed at, trivialized, pushed, ignored, stereotyped, kicked, scorned, molested, silenced, invalidated, knifed, shot, choked, and killed ...

BECAUSE every time we pick up a pen, or an instrument, or get anything done, we are creating the revolution. We ARE the revolution.”

— Reinstein, Fantastic Fanzine no. 2 (zine)

Girls used these zines to discuss their personal experiences, and commonly discussed themes include body image and sexuality as well as sexual violence, assault, abuse, and incest.[8][11] As first-person, grassroots texts,[8] girl zines emphasize lived experiences.[12] Girl zines also use a variety of rhetorical tropes that include expressions of intense anger, reclamation and refiguring of femininity, and juxtaposition of unassociated images or ideas.[8] Riot grrrl zines also employ an "aesthetics of access" or "revelatory confessional modes" that inspires intimacy with imagined readers and the riot grrrl community. Scholar and zinester Mimi Thi Nguyen notes that these norms unequally burdened riot grrrls of color with allowing white riot grrrls access to their personal experiences, an act which in itself was supposed to address systemic racism.[13]

Despite predictions that zines would die out with the rise of blogging and the Internet, women zinesters are still creating zines.[8] Many zinesters believe writing zines allow women to avoid harassment they might receive on more public blogs and allows for a more material record of their work.[8] Many of these zines are now housed in archival collections around the world, which are becoming increasingly important sites of feminist practice.[14]

Zines and the Internet

With the rise of the Internet in the late 1990s, zines initially faded from public awareness. It can be argued that the sudden growth of the Internet, and the ability of private web-pages to fulfill much the same role of personal expression as zines, was a strong contributor to their pop culture expiration. Indeed, many zines were transformed into websites, such as Boingboing or monochrom. However, zines have subsequently been embraced by a new generation, often drawing inspiration from craft, graphic design and artists' books, as well as for political and subcultural reasons.

Distribution and circulation

Zines are sold, traded or given as gifts through many different outlets, from zine symposiums and publishing fairs to record stores, book stores, zine stores, at concerts, independent media outlets, zine 'distros', via mail order or through direct correspondence with the author. They are also sold online either via websites, Etsy shops, or social networking profiles.

Zines distributed for free are either traded directly between zinesters, given away at the outlets mentioned or are available to download and print online.

Webzines are found in many places on the Internet.

Publishing

While zines are generally self-published, there are a few independent publishers who specialise in making art zines. One such 'art-zine' publisher (who also publishes books) is Nieves Books in Zurich, founded by Benjamin Sommerhalder. Another is Café Royal Books, UK based and founded by Craig Atkinson in 2005.

Distributors

Zines are most often obtained through mail-order distributors. There are many catalogued and online based mail-order distros for zines. Some of the longer running and most stable operations include Last Gasp in San Francisco, California,[15] Parcell Press in Philadelphia, Microcosm Publishing in Portland, Oregon, Great Worm Express Distribution in Toronto, CornDog Publishing in Ipswich in the UK, Café Royal Books in Southport in the UK, Fistful of Books in Scotland, AK Press in Oakland, California,[16] Missing Link Records in Melbourne[17] and Soft Skull Press in Brooklyn, New York.[18] Zine distros often have websites one can place orders on. Because these are small scale DIY projects run by an individual or small group, they often close after only a short time of operation. Those that have been around the longest are often the most dependable.

Zines in libraries

A number of major public and academic libraries carry zines and other small press publications, often with a specific focus (e.g. women's studies) or those that are relevant to a local region.

Libraries with notable zine collections include Barnard College Library and the University of Iowa Special Collections.[19][20] The Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History and Culture at Duke University has one of the largest collections of zines on the east coast, housed in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[21] Jenna Freedman is the founder and archivist of the Barnard College Zine collection. Freedman says zines are important because zinesters are "people controlling their own content and style" and also offers voices from "people with radical points of view."[22] Librarian Julie Bartel of the Salt Lake City Public Library argues that starting or maintaining a zine collection adheres to the American Library Association's Library Bill of Rights and principles of intellectual freedom. Bartel believes that librarians should be placing more of an emphasis on providing a wide array of ideas, regardless where the ideas come from (established publishing houses vs. self-published work) and how they are presented (professionally published books vs. zines).[23]

The Indie Photobook Library, an independent archive in the Washington, DC area, has a large collection of photobook zines from 2010 to the present.[24]

The metadata standard for cataloging zines is xZineCorex, which maps to Dublin Core.[25]

In science fiction

Science fiction fanzines vary in content, from short stories to convention reports to fanfiction. They were one of the earliest incarnations of the zine and influenced subsequent zines in topics such as rock 'n roll and LGBT rights.[26] "Zinesters" like Lisa Ben and Jim Kepner honed their talents in the science fiction fandom before tackling gay rights, creating zines such as “Vice Versa” and “ONE” that drew networking and distribution ideas from their SF roots.[27] Zines were often used to publish content that would have more difficulty in the mainstream market and would not otherwise be published. This was utilized by marginalized authors as a way to share their works.[8]

Star Trek Zines

Some of the earliest examples of academic fandom were written on Star Trek zines, specifically K/S (Kirk/Spock) slash zines. Author Joanna Russ wrote in her 1985 analysis of K/S zines that slash fandom at the time consisted of around 500 core fans and was 100% female.[28]

She wrote that, "K/S not only speaks to my condition. It is written in Female. I don't mean that literally, of course. What I mean is that I can read it without translating it from the consensual, public world, which is sexist, and unconcerned with women per se, and managing to make it make sense to me and my condition." [29] Unlike women authors who write "slant" against traditional (male) literature, Russ says that K/S is an art that is "truly ours."

Russ also observed that while SF fans looked down on Star Trek fans, Star Trek fans looked down on K/S writers.[29]

Kirk/Spock zines contained fanfiction, artwork, and poetry created by fans. They were then sent to a mailing list or sold at conventions. Many of the zines had high production values and some were sold at convention auctions for hundreds of dollars.[28]

Janus and Aurora

Janus, later called Aurora, was a science fiction feminist zine created by Janice Bogstad and Jeanne Gomoll in 1975. It contained short stories, essays, and film reviews. Among its contributors were authors such as Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ, Samuel R. Delany, and Suzette Hayden Elgin.[30] Janus/Aurora was nominated for the Hugo Award for "Best Fanzine" in 1978, 1979, and 1980. Janus/Aurora was the most prominent science fiction feminist zine during its run, as well as one of the only zines that dealt with such content.[31]

In punk

Zines played an important role in spreading information about different scenes in the punk era (e.g. British fanzines like Mark Perry’s Sniffin Glue and Shane MacGowan’s Bondage).

In the pre-Internet era, zines enabled readers to learn about bands, clubs, and record labels. Zines typically included reviews of shows and records, interviews with bands, letters, and ads for records and labels. Zines were DIY products, "proudly amateur, usually handmade, and always independent" and in the "’90s, zines were the primary way to stay up on punk and hardcore." They acted as the "blogs, comment sections, and social networks of their day."

In the American Midwest, the zine Touch and Go described the Midwest hardcore scene from 1979 to 1983. We Got Power described the LA scene from 1981 to 1984, and it included show reviews and band interviews with groups including D.O.A., the Misfits, Black Flag, Suicidal Tendencies and the Circle Jerks. My Rules was a photo zine that included photos of hardcore shows from across the US. In Effect, which began in 1988, described the New York City scene.

By 1990, Maximum Rocknroll "had become the de facto bible of the scene. A thick, monthly, cheaply printed wad of newsprint crammed with tiny print that came off on the hands", MRR had a "passionate yet dogmatic view" of what hardcore was supposed to be (as an example, MRR declined to review a prominent early emo record by Still Life). HeartattaCk and Profane Existence were "even more religious about its DIY ethos." HeartattaCk was mainly about emo and post-hardcore. Profane Existence was mostly about crust punk.

The Bay Area zine Cometbus "captured an entire dimension of ’90s punk culture that provided necessary roughage compared to the empty calories of mainstream punk’s MTV/Warped Tour narrative." Other 1990 zines included Gearhead, Slug and Lettuce and Riot Grrrl. In Canada, the zine Standard Issue chronicles the Ottawa hardcore scene.

With the arrival of the Internet, some hardcore punk zines became available online. One example is the e-zine chronicling the Australian hardcore scene, RestAssured.

alt.zines

The Usenet newsgroup alt.zines was created in 1992 by Jerod Pore and Edward Vielmetti for the discussion of zines and zine-related topics. Since that time, alt.zines has seen more than 26,000 postings.

From the original alt.zines charter: "alt.zines is a place for reviews of zines, announcements of new zines, tips on how to make zines, discussions of the culture of zines, news about zines, specific zines and related stuff."

"Related stuff" has included almost everything under the sun. Throughout the 1990s alt.zines was really the only forum for zinesters to promote, talk, and discuss small publishing issues and tips. And of course argue. It was a place where a zine reader or first time publisher could rub elbows with infamous zinesters.

While today there are many other online forums for zinesters and traffic on alt.zines has slowed down dramatically since the zinester flame wars of yesteryear, alt.zines remains one of the most influential places on the web for zine publishers and readers alike. Many long-time alt.zines participants now contribute to ZineWiki.

See also

References

- ↑ William E. Jones, True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and "Straight to Hell", Los Angeles: We Heard You Like Books, 2016, ISBN 9780996421812, p. 6.

- ↑ "About Zines: Definition". New York, N.Y.: Barnard Zine Library; Barnard College.

- ↑ "Zine, n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Piepmeier, Alison (2009). Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. NYU Press. p. 215 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dunn, Kevin (2016). Global Punk: Resistance and Rebellion in Everyday Life. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 163 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "zine info". www.allthumbspress.net. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ↑ "Early Irish fanzines". Loserdomzine.com. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Piepmeier, Alison (2009). Girl Zines: making media, doing feminism. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814767528. OCLC 326484782.

- ↑ Dunn, Kevin; Farnsworth, May Summer (2012). ""We Are The Revolution": Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-publishing". Women's studies. 41 (136-137): 142, 147, 150. doi:10.1080/00497878.2012.636334.

- ↑ Dunn, Kevin; Farnsworth, May Summer (March 2012). ""We ARE the Revolution": Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing". Women's Studies. 41 (2): 141. ISSN 0049-7878.

- ↑ Sinor, Jennifer (2003). "Another Form of Crying: Girl Zines as Life Writing". Prose Studies: History, Theory, Criticism. 26 (1-2): 246. doi:10.1080/0144035032000235909.

- ↑ Licona, Adela (2012). Zines in third space : radical cooperation and borderlands rhetoric. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 8. ISBN 1438443722.

- ↑ Nguyen, Mimi Thi (12 December 2012). "Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival". Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory. 22 (2-3): 173–196. doi:10.1080/0740770X.2012.721082. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ Eichhorn, Kate (2013). The archival turn in feminism outrage in order. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781439909539.

- ↑ "Last Gasp Books". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Welcome to AK Press". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Missing Link Digital". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Soft Skull: Home". Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Zine and Amateur Press Collections at the University of Iowa". Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Hevelin Collection". Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Bingham Center Zine Collections". Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Katz, Brigit (2014-02-16). "Totally rad: an interview with Jenna Freedman, activist librarian". Bibliopaths. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ↑ Bartel, Julie (2005). From A to Zine : Building a Winning Zine Collection in Your Library. ALA Editions. p. 28 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ http://www.indiephotobooklibrary.org/

- ↑ Miller, Milo. "xZineCorex: An Introduction" (PDF). Milo Miller. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bingham Center Zine Collections |". library.duke.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ↑ "LGBT found a voice in science fiction". Southern California Public Radio. http://www.scpr.org/programs/offramp/2015/09/04/44365/how-gay-rights-got-its-start-in-science-fiction/. 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2015-10-24. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 Grossberg, Lawrence; Nelson, Cary; Treichler, Paula (2013-02-01). Cultural Studies. Routledge. ISBN 9781135201265.

- 1 2 "Concerning K/S." Joanna Russ Papers, Series II: Literary Works: Box 13, Folder #, Page 25. University of Oregon Special Collections.

- ↑ "Culture : Janus/Aurora : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "Janus & Aurora |". sf3.org. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

Further reading

- Anderberg, Kirsten. Alternative Economies, Underground Communities: A First Hand Account of Barter Fairs, Food Co-ops, Community Clinics, Social Protests and Underground Cultures in the Pacific Northwest & CA 1978-2012. USA: 2012.

- Anderberg, Kirsten. Zine Culture: Brilliance Under the Radar. Seattle, USA: 2005.

- Bartel, Julie. From A to Zine: Building a Winning Zine Collection in Your Library. American Library Association, 2004.

- Biel, Joe $100 & a T-shirt: A Documentary About Zines in the Northwest. Microcosm Publishing, 2004, 2005, 2008 (Video)

- Block, Francesca Lia and Hillary Carlip. Zine Scene: The Do It Yourself Guide to Zines. Girl Press, 1998.

- Brent, Bill. Make a Zine!. Black Books, 1997 (1st edn.), ISBN 0-9637401-4-8. Microcosm Publishing, with Biel, Joe, 2008 (2nd edn.), ISBN 978-1-934620-06-9.

- Brown, Tim W. Walking Man, A Novel. Bronx River Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9789847-0-0.

- Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm Publishing, 1997, 2008. ISBN 1-85984-158-9.

- Kennedy, Pagan. Zine: How I Spent Six Years of My Life in the Underground and Finally...Found Myself...I Think (1995) ISBN 0-312-13628-5.

- Klanten, Robert, Adeline Mollard, Matthias Hübner, and Sonja Commentz, eds. Behind the Zines: Self-Publishing Culture. Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag, 2011.

- Piepmeier, Alison . Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. NYU Press. (2009) ISBN 978-0-8147-6752-8.

- Spencer, Amy. DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture. Marion Boyars Publishers, Ltd., 2005.

- Watson, Esther and Todd, Mark. "Watcha Mean, What's a Zine?" Graphia, 2006. ISBN 978-0-618-56315-9.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 1 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-0-7.

- Vale, V. Zines! Volume 2 (RE/Search, 1996) ISBN 0-9650469-2-3.

- Wrekk, Alex. Stolen Sharpie Revolution. Portland: Microcosm Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-9726967-2-5.

- Richard Hugo House Zine Archives and Publishing Project (ZAPP). "ZAPP Seattle". Seattle, USA.

External links

| Look up zine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Zine making |

- alti.zines newsgroup

- Sticky Institute's We Make Zines

- Zinewiki

- Barnard Zine Library: About Zines Elsewhere Directory of zine collections and websites