American Humanist Association

| |

| Abbreviation | AHA |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1941 |

| Type | Non-profit |

| Purpose | Advocate for progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, agnostics, and freethinkers. |

| Location | |

Key people |

Rebecca Hale (President) David Niose (Immediate Past President) Roy Speckhardt (Executive Director) |

| Website | www.americanhumanist.org |

The American Humanist Association (AHA) is an educational organization in the United States that advances Secular Humanism, a philosophy of life that, without theism or other supernatural beliefs, affirms the ability and responsibility of human beings to lead personal lives of ethical fulfillment that aspire to the greater good of humanity.[1]

The American Humanist Association was founded in 1941 and currently provides legal assistance to defend the constitutional rights of secular and religious minorities,[2] actively lobbies Congress on church-state separation and other issues,[3] and maintains a grassroots network of 150 local affiliates and chapters that engage in social activism, philosophical discussion and community-building events.[4] The AHA has several publications, including the bi-monthly magazine The Humanist, a quarterly newsletter Free Mind, a peer-reviewed semi-annual scholastic journal Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism, and a daily online news site TheHumanist.com.[5]

Background

| Part of a Philosophy series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| History |

| Secular humanism |

| Religious humanism |

| Other forms |

| Organizations |

| See also |

|

Philosophy portal |

In 1927 an organization called the "Humanist Fellowship" began at a gathering in Chicago. In 1928 the Fellowship started publishing the New Humanist magazine. H.G. Creel was the first editor. The New Humanist was published from 1928 to 1936. By 1935 the Humanist Fellowship had become the "Humanist Press Association", the first national association of humanism in the United States.[6]

The first Humanist Manifesto was issued by a conference held at the University of Chicago in 1933. Signatories included the philosopher John Dewey, but the majority were ministers (chiefly Unitarian) and theologians. They identified humanism as an ideology that espouses reason, ethics, and social and economic justice.[7]

In July 1939 a group of Quakers, inspired by the 1933 Humanist Manifesto, incorporated under the state laws of California the Humanist Society of Friends as a religious, educational, charitable nonprofit organization authorized to issue charters anywhere in the world and to train and ordain its own ministry. Upon ordination these ministers were then accorded the same rights and privileges granted by law to priests, ministers, and rabbis of traditional theistic religions.[8]

History

Curtis Reese was a leader in the 1941 reorganization and incorporation of the "Humanist Press Association" as the American Humanist Association. Along with its reorganization, the AHA began printing The Humanist magazine. The AHA was originally headquartered in Yellow Springs, Ohio, then San Francisco, California, and in 1978 Amherst, New York.[6] Subsequently, the AHA moved to Washington, D.C..

In 1952 the AHA became a founding member of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) in Amsterdam, Netherlands.[9] As an international coalition of Humanist organizations, the IHEU stands today as the only international umbrella group for Humanism.

The AHA was the first national membership organization to support abortion rights. Around the same time, the AHA joined hands with the American Ethical Union (AEU) to help establish the rights of nontheistic conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War. This time also saw Humanists involved in the creation of the first nationwide memorial societies, giving people broader access to cheaper alternatives than the traditional burial. In the late 1960s the AHA also secured a religious tax exemption in support of its celebrant program, allowing Humanist celebrants to legally officiate at weddings, perform chaplaincy functions, and in other ways enjoy the same rights as traditional clergy.

In 1991 the AHA took control of the Humanist Society, a religious Humanist organization that now runs the celebrant program. Since 1991 the organization has worked as an adjunct to the American Humanist Association to certify qualified members to serve in this special capacity as ministers. The Humanist Society's ministry prepares Humanist Celebrants to lead ceremonial observances across the nation and worldwide. Celebrants provide millions of Americans an alternative to traditional religious weddings, memorial services, and other life cycle events.[10] After this transfer, the AHA commenced the process of jettisoning its religious tax exemption and resumed its exclusively educational status. Today the AHA is recognized by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service as a nonprofit, tax exempt, 501(c)(3), publicly supported educational organization.

Membership numbers are disputed, but Djupe and Olson place it under 50,000.[11] The AHA has over 575,000 followers on Facebook and over 42,000 followers on Twitter.[12][13]

Adjuncts and affiliates

The AHA is also the supervising organization for various Humanist affiliates and adjunct organizations.

Black Humanist Alliance

The Black Humanist Alliance of the American Humanist Association was founded in 2016 as a pillar of its new "Initiatives for Social Justice."[14] Like the Feminist Humanist Alliance and the LGBT Humanist Alliance, the Black Humanist Alliance uses an intersectional approach to addressing issues facing the Black community. As its mission states, the BHA "concern ourselves with confronting expressions of religious hegemony in public policy," but is "also devoted to confronting social, economic, and political deprivations that disproportionately impact Black America due to centuries of culturally ingrained prejudices."[15]

Feminist Humanist Alliance

The Feminist Humanist Alliance (formerly the Feminist Caucus) of the American Humanist Association was established in 1977 as a coalition of both women and men within the AHA to work toward the advancement of women's rights and equality between the sexes in all aspects of society. Originally called the Women's Caucus, the new name was adopted in 1985 as more representative of all the members of the caucus and of the caucus' goals. Over the years, members of the Caucus have advocated for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and participated in various public demonstrations, including marches for women's and civil rights. In 1982, the Caucus established its annual Humanist Heroine Award, with the initial award being presented to Sonia Johnson. Other Humanist Heroines include Tish Sommers, Christine Craft, and Fran Hosken.[16] In 2012 the Feminist Caucus declared it would be organizing around two principal efforts: "Refocusing on passing the ERA" and "Promoting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights."[17]

In 2016, the Feminist Caucus, mirroring the Black Humanist Alliance and the LGBT Humanist Alliance, reorganized as the Feminist Humanist Alliance as a component of their larger "Initiatives for Social Justice." [14] As stated on its website, the "refinement in vision" emphasized "FHA's more active partnership with outreach programs and social justice campaigns with distinctly inclusive feminist objectives."[18] Its current goal is to provide a "movement powered by and for women, transpeople, and genderqueer people to fight for social justice. We are united to create inclusive and diverse spaces for activists and allies on the local and national level."[19]

LGBTQ Humanist Alliance

The LGBTQ Humanist Alliance (formerly LGBT Humanist Council) of the American Humanist Association is committed to advancing equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and their families. The alliance "seeks to cultivate safe and affirming communities, promote humanist values, and achieve full equality and social liberation of LGBTQ persons."[20]

Paralleling the Black Humanist Alliance and the Feminist Humanist Alliance, the Council reformed in 2016 as the LGBTQ Humanist Alliance as a larger part of the AHA's "Initiatives for Social Justice."[14]

Humanist Charities

Humanist Disaster Recovery (formerly Humanist Charities) was established in 2005 and its purpose includes applying uniquely Humanist approaches to those in need and directing the generosity of American humanists to worthy disaster relief and development projects around the world. In 2011 Humanist Charities raised $5,000 from AHA members to donate to the Japan Earthquake Relief Fund.[21]

In September 2008 Humanist Charities raised over $2,500 for the Children of the Border project, a relief and development project to expand emergency medical service and health care for expectant mothers living in the Haitian border region of the Dominican Republic.[22]

In June 2014 Humanist Charities joined forces with the Foundation Beyond Belief's Humanist Crisis Reposonse to form Humanist Disaster Recovery. AHA's Executive Director Roy Speckhardt commented that, “This merger is a positive move that will grow the relief efforts of the humanist community. The end result will be more money directed to charitable activities, dispelling the false claim that nonbelievers don’t give to charity.” As such, the American Humanist Association agreed to promote and raise awareness of Humanist Disaster Recovery while the Foundation Beyond Belief managed its implementation.[23]

Between 2013-2016, Humanist Disaster Recovery has raised funds for victims of the Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, the Syrian Refugee Crisis, Refugee Children of the U.S. Border, Tropical Cyclone Sam, and the Nepal and Ecuadoran Earthquakes.[24] They also facilitate a volunteer network called the Humanist Disaster Recovery (HDR) Teams, who directly help communities in need.[25] The HDR Teams helped to rebuild homes in Columbia, South Carolina after the effects of Hurricane Joaquin.[26]

Appignani Humanist Legal Center

The American Humanist Association launched the Appignani Humanist Legal Center (AHLC) in 2006 to ensure that humanists' constitutional rights are represented in court. Through amicus activity, litigation, and legal advocacy, a team of cooperating lawyers, including Jim McCollum, Wendy Kaminer, and Michael Newdow, provide legal assistance by challenging perceived violations of the Establishment Clause.

- The AHLC’s first independent litigation was filed on November 29, 2006, in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. Attorney James Hurley, the AHLC lawyer serving as lead counsel, filed suit against the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections on behalf of Plaintiff Jerry Rabinowitz, whose polling place was a church in Delray Beach, Florida. The church featured numerous religious symbols, including signs exhorting people to “Make a Difference with God” and anti-abortion posters, which the AHLC claimed demonstrated a violation of the Establishment Clause. In the voting area itself, "Rabinowitz observed many religious symbols in plain view, both surrounding the election judges and in direct line above the voting machines. He took photographs that will be entered in evidence."[27] U.S. District Judge Donald M. Middlebrooks ruled that Jerry Rabinowitz did not have standing to challenge the placement of polling sites in churches, and dismissed the case.[28]

- In February 2014, AHA brought suit to force the removal of the Bladensburg Peace Cross, a war memorial honoring 49 residents of Prince George's County, Maryland, who died in World War I. AHA represented the plaintiffs, Mr. Lowe, who drives by the memorial "about once a month" and Fred Edwords, former AHA Executive director.[29][30] AHA argued that the presence of a Christian religious symbol on public property violates the First Amendment clause prohibiting government from establishing a religion. Town officials feel the monument to have historic and patriotic significant to local residents.[30][31] A member of the local American Legion Post said, "I mean, to me, it's like they're slapping the veterans in the face. I mean, that's a tribute to the veterans, and for some reason, I have no idea what they have against veterans. I mean, if it wasn't for us veterans they wouldn't have the right to do what they're trying to do."[32]

- In March 2014, a Southern California woman reluctantly removed a roadside memorial from near a freeway ramp where her 19-year-old son was killed after the AHA contacted the city council calling the cross on city-owned property a "serious constitutional violation".[33]

- AHLC represented an atheist family who claimed that the equal rights amendment of the Massachusetts constitution prohibits mandatory daily recitations of the Pledge of Allegiance because the anthem contains the phrase “under God.” In November 2012 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court permitted a direct appeal with oral arguments set for early 2013.[34] In May 2014, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in a unanimous decision that the daily recitation of the phrase “under god” in the US Pledge of Allegiance does not violate the plaintiffs' equal protection rights under the Massachusetts Constitution.

- In February 2015 New Jersey Superior Court Judge David F. Bauman dismissed a lawsuit challenging the Pledge of Allegiance, ruling that "...the Pledge of Allegiance does not violate the rights of those who don't believe in God and does not have to be removed from the patriotic message."[35] In a twenty-one page decision, Bauman wrote, "Under (the association members') reasoning, the very constitution under which (the members) seek redress for perceived atheistic marginalization could itself be deem unconstitutional, an absurd proposition which (association members) do not and cannot advance here."[35]

Advertising campaigns

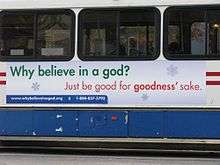

The American Humanist Association has received media attention for its various advertising campaigns; in 2010, the AHA's campaign was said to be the more expensive than similar ad campaigns from the American Atheists and Freedom From Religion Foundation.[36]

In 2008 the AHA ran ads on buses in Washington, D.C. that proclaimed "Why believe in a god? Just be good for goodness' sake",[37] and since 2009 the organization has paid for billboard advertisements nationwide.[38] One such billboard, which stated "No God...No Problem" was repeatedly vandalized.[39]

In 2010 the AHA launched another ad campaign promoting Humanism, which the New York Times said was the "first (atheist campaign) to include spots on television and cable"[40] and was described by CNN as the "largest, most extensive advertising campaign ever by a godless organization".[41] The campaign featured violent or sexist quotes from holy books, contrasted with quotes from humanist thinkers, including physicist Albert Einstein, biologist Richard Dawkins, and anthropologist Carleton Coon, and was largely underwritten by Todd Stiefel, a retired pharmaceutical company executive.[40]

In late 2011 the AHA launched a holiday billboard campaign, placing advertisements in 7 different cities: Kearny, New Jersey; Washington, D.C.; Cranston, Rhode Island; Bastrop, Louisiana; Oregon City, Oregon; College Station, Texas and Rochester Hills, Michigan", cities where AHA states "atheists have experienced discrimination due to their lack of belief in a traditional god".[42] The organization spent more than $200,000 on their campaign which included a billboard reading "Yes, Virginia, there is no god.".[43]

In November 2012, the AHA launched a national ad campaign to promote a new website, KidsWithoutGod.com, with ads using the slogans "I'm getting a bit old for imaginary friends" [44] and "You're Not The Only One." [45] The campaign included bus advertising in Washington, DC, a billboard in Moscow, Idaho, and online ads on the family of websites run by Cheezburger and Pandora Radio, as well as Facebook, Reddit, Google, and YouTube.[46] Ads were turned down for content by Disney, Time for Kids and National Geographic Kids.[47]

National Day of Reason

The National Day of Reason was created by the American Humanist Association and the Washington Area Secular Humanists in 2003. In addition to serving as a holiday for secularists, the National Day of Reason was created in response to the perceived unconstitutionality of the National Day of Prayer. According to the organizers of the National Day of Reason, the National Day of Prayer, "violates the First Amendment of the United States Constitution because it asks federal, state, and local government entities to set aside tax dollar supported time and space to engage in religious ceremonies".[48]

Several organizations associated with the National Day of Reason have organized food drives and blood donations, while other groups have called for an end to prayer invocations at city meetings.[49][50] Other organizations, such as the Oklahoma Atheists and the Minnesota Atheists, have organized local secular celebrations as alternatives to the National Day of Prayer.[51] Additionally, many individuals affiliated with these atheistic groups choose to protest the official National Day of Prayer.[52]

Reason Rally

In 2012, the American Humanist Association co-sponsored the Reason Rally, a national gathering of "humanists, atheists, freethinkers and nonbelievers from across the United States and abroad" in Washington, D.C.[53] The rally, held on the National Mall, had speakers such as Richard Dawkins, James Randi, Adam Savage, and student activist Jessica Ahlqvist. AHA Executive Director Roy Speckhardt also spoke. According to the Huffington Post, the event's attendance was between 8,000-10,000 while the Atlantic reported a crowd of nearly 20,000.[54][55]

The AHA also co-sponsored the 2016 Reason Rally, held at the Lincoln Memorial.[56]

Famous awardees

The American Humanist Association has named a "Humanist of the Year" annually since 1953. It has also granted other honors to numerous leading figures, including Salman Rushdie (Outstanding Lifetime Achievement Award in Cultural Humanism 2007), Oliver Stone (Humanist Arts Award, 1996), Katharine Hepburn (Humanist Arts Award 1985), John Dewey (Humanist Pioneer Award, 1954), Jack Kevorkian (Humanist Hero Award, 1996) and Vashti McCollum (Distinguished Service Award, 1991).

AHA's Humanists of the Year

The AHA website presents the list of the following Humanists of the Year:[57]

- Anton J. Carlson - 1953

- Arthur F. Bentley - 1954

- James P. Warbasse - 1955

- C. Judson Herrick - 1956

- Margaret Sanger - 1957

- Oscar Riddle - 1958

- Brock Chisholm - 1959

- Leó Szilárd - 1960

- Linus Pauling - 1961

- Julian Huxley - 1962

- Hermann J. Muller - 1963

- Carl Rogers - 1964

- Hudson Hoagland - 1965

- Erich Fromm - 1966

- Abraham H. Maslow - 1967

- Benjamin Spock - 1968

- R. Buckminster Fuller - 1969

- A. Philip Randolph - 1970

- Albert Ellis - 1971

- B.F. Skinner - 1972

- Thomas Szasz - 1973

- Joseph Fletcher - 1974

- Mary Calderone - 1974

- Henry Morgentaler - 1975

- Betty Friedan - 1975

- Jonas E. Salk - 1976

- Corliss Lamont - 1977

- Margaret E. Kuhn - 1978

- Edwin H. Wilson - 1979

- Andrei Sakharov - 1980

- Carl Sagan - 1981

- Helen Caldicott - 1982

- Lester A. Kirkendall - 1983

- Isaac Asimov - 1984

- John Kenneth Galbraith - 1985

- Faye Wattleton - 1986

- Margaret Atwood - 1987

- Leo Pfeffer - 1988

- Gerald A. Larue - 1989

- Ted Turner - 1990

- Lester R. Brown - 1991

- Kurt Vonnegut - 1992

- Richard D. Lamm - 1993

- Lloyd Morain - 1994

- Mary Morain - 1994

- Ashley Montagu - 1995

- Richard Dawkins - 1996

- Alice Walker - 1997

- Barbara Ehrenreich - 1998

- Edward O. Wilson - 1999

- William F. Schulz - 2000

- Stephen Jay Gould - 2001

- Steven Weinberg - 2002

- Sherwin T. Wine - 2003

- Daniel Dennett - 2004

- Murray Gell-Mann - 2005

- Steven Pinker - 2006

- Joyce Carol Oates - 2007

- Pete Stark - 2008

- PZ Myers - 2009

- Bill Nye - 2010

- Rebecca Goldstein - 2011

- Gloria Steinem - 2012

- Dan Savage - 2013

- Barney Frank - 2014

- Lawrence M. Krauss - 2015

- Jared Diamond - 2016

See also

References

- ↑ "About Humanism". Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ "AHLC mission statement". Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ↑ "AHA Action Center". Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ↑ "Local Group Information". Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ↑ List of Publications americanhumanist.org (Retrieved 2011-10-01)

- 1 2 Harris, Mark W., The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism, Scarecrow Press, 2009 ISBN 9780810863330

- ↑ Walter, Nicolas. Humanism: What's in the Word? (London: RPA/BHA/Secular Society Ltd, 1937), p.43.

- ↑ "Humanist Society's Early History". Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "IHEU founding". Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- ↑ "Humanist Society's Services". Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ Djupe, Paul A. and Olsen, Laura R., "American Humanist Association", Encyclopedia of American Religion and Politics", Infobase Publishing, 2014

- ↑ "Security Check Required". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "American Humanist (@americnhumanist) | Twitter". twitter.com. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- 1 2 3 "Humanist Group Launches Initiatives for Racial Justice, Women's Equality and LGBTQ Rights". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Mission - The Black Humanist Alliance - Menu". blackhumanists.org. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Feminist Caucus Previous Work". Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "The Feminist Caucus of the American Humanist Association". Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- ↑ "History - Feminist Humanist Alliance". feministhumanists.org. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "What We Do - Feminist Humanist Alliance". feministhumanists.org. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "About the LGBTQ Humanist Alliance". LGBTQ Humanist Alliance. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Recent Projects". Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "Humanist Charities Past Work". Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "Humanist Charities and Humanist Crisis Response Announce Merger". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "Humanist Disaster Recovery Drive". Foundation Beyond Belief. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "Humanist Disaster Recovery Teams". Foundation Beyond Belief. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ "HDR Teams: South Carolina 2016". Foundation Beyond Belief. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- ↑ Jones, Susan (2006-11-30). "'Humanists' Challenge Voting Booths in Churches". crosswalk.com. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "Voting in churches is constitutional, says Florida federal court.". www.thefreelibrary.com. 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- ↑ Brown, Matthew Hay. "Veterans' cross in Maryland at the center of national battle", Baltimore Sun, May 25, 2014

- 1 2 Kuruvilla, Carol. "Humanists suing to tear down cross-shaped World War I memorial", Daily News, March 1, 2014

- ↑ Jacobs, Danny. "Bladensburg Peace Cross Sparks Legal War", Daily Record, March 1, 2014

- ↑ "Bladensburg residents argue over WWI memorial". WJLA. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Mother Removes Cross Memorial After Dispute With Atheist Rights Group". NBC Southern California. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "SJC to hear case from atheist family". Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- 1 2 "'Under God' is not discriminatory and will stay in pledge, judge says". NJ.com. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Laurie Goodstein, Atheist Groups Promote a Holiday Message: Join Us, New York Times (November 9, 2010).

- ↑ "'Why Believe in a God?' Ad Campaign Launches on D.C. Buses". Fox News. 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "American Humanist Association | 2009". Americanhumanist.org. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ "Humanists replace billboard for the second time | News | KLEW CBS 3 - News, Weather and Sports - Lewiston, ID". Klewtv.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- 1 2 Goodstein, Laurie (2010-11-09). "Atheists' Holiday Message: Join Us". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Humanists launch huge 'godless' ad campaign". CNN. 2010-11-09.

- ↑ "Humanists Launch "Naughty" Awareness Campaign". Americanhumanist.org. 2011-11-21. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ "Ad Campaign Promoting Atheism Across U.S. Draws Ire and Protest - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ Duke, Barry (2012-11-14). "Getting too old for imaginary friends? American humanists have the answers". Freethinker.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ "Kids Without God ad campagin". Americanhumanist.org. 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ "National ad campaign promotes KidsWithoutGod.com on buses and online". Secular News Daily. 2012-11-14. Archived from the original on 2012-11-24. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ "Atheist Ad Campaign Promotes Kids Without God; Already, Companies Are Refusing to Run Ads". Patheos.com. 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- ↑ National Day of Reason History

- ↑ "Positive Protest Against the Day of Prayer! (Center for Atheism, New York)". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Janet Zinc (May 6, 2010). "On National Day of Prayer, atheists renew call to end invocations at Tampa city meetings". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ Minnesota Atheists Day of Reason Archived October 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "National Day of Reason May 5, 2011". WordPress.com. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ "American Humanist Association Sponsors Reason Rally, Largest Atheist Event in History". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "PHOTOS: Atheists Rally On National Mall For Political Change". The Huffington Post. 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ Woods, Benjamin Fearnow and Mickey. "Richard Dawkins Preaches to Nonbelievers at Reason Rally". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "American Humanist Association to Co-Sponsor Reason Rally 2016, National Gathering of Humanists and Atheists". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "The Humanist of the Year". American Humanist Association. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to American Humanist Association. |

- Official website

- American Humanist Association at GuideStar

- "Edwin H. Wilson Papers of the American Humanist Association, 1913-1989". Special Collections Research Center. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University.

- Bladensburg War Memorial in Town of Bladensburg