Andrea Doria-class battleship

Andrea Doria during World War I | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: | |

| Preceded by: | Conte di Cavour class |

| Succeeded by: |

|

| Built: | 1912–16 |

| In service: | 1915–53 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 2 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 24,729 long tons (25,126 t) (deep load) |

| Length: | 176 m (577 ft 5 in) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 28 m (91 ft 10 in) |

| Draft: | 9.4 m (30 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 4,800 nmi (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| General characteristics (after reconstruction) | |

| Displacement: | 28,882–29,391 long tons (29,345–29,863 t) (deep load) |

| Length: | 186.9 m (613 ft 2 in) |

| Beam: | 28.03 m (92 ft 0 in) |

| Draft: | 10.3 m (33 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) |

| Range: | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,520 |

| Armament: |

|

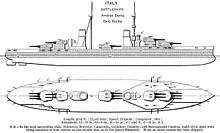

The Andrea Doria class (usually called Caio Duilio class in Italian sources) was a pair of dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) during the early 1910s. The two ships—Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio—were completed during World War I. The class was an incremental improvement over the preceding Conte di Cavour class. Like the earlier ships, Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio were armed with a main battery of thirteen 305-millimeter (12.0 in) guns.

The two ships spent World War I based in southern Italy to keep the Austro-Hungarian Navy bottled up in the Adriatic, but neither vessel saw any combat. After the war, they cruised the Mediterranean and were involved in several international incidents, including the Corfu Incident in 1923. Both ships were placed in reserve a decade later and began a lengthy reconstruction in 1937. The modifications included removing their center main battery turret and boring out the rest of the guns to 320 mm (12.6 in), strengthening their armor protection, installing new boilers and steam turbines, and lengthening their hulls. The reconstruction work lasted until 1940, by which time Italy was already engaged in World War II.

The two ships were moored in Taranto on the night of 11/12 November 1940 when the British launched a carrier strike on the Italian fleet. In the resulting Battle of Taranto, Caio Duilio was hit by a torpedo and forced to beach to avoid sinking. Andrea Doria was undamaged in the raid; repairs for Caio Duilio lasted until May 1941. Both ships escorted convoys to North Africa in late 1941, including Operation M42, where Andrea Doria saw action at the inconclusive First Battle of Sirte on 17 December. Fuel shortages curtailed further activity in 1942 and 1943, and both ships were interned at Malta following Italy's surrender in September 1943. Italy was permitted to retain both battleships after the war, and they alternated as fleet flagship until the early 1950s, when they were removed from active service. Both ships were scrapped after 1956.

Design and description

The Andrea Doria-class ships were designed by naval architect Vice Admiral (Generale del Genio navale) Giuseppe Valsecchi and were ordered in response to French plans to build the Bretagne-class battleships. The design of the preceding Conte di Cavour-class battleships was generally satisfactory and was adopted with some minor changes. These mostly concerned the reduction of the superstructure by shortening the forecastle deck, the consequent lowering of the amidships gun turret and the upgrading of the secondary armament to sixteen 152-millimeter (6 in) guns in lieu of the eighteen 120-millimeter (4.7 in) guns of the older ships.[1]

General characteristics

The ships of the Andrea Doria class were 168.9 meters (554 ft 2 in) long at the waterline, and 176 meters (577 ft 5 in) overall. They had a beam of 28 meters (91 ft 10 in), and a draft of 9.4 meters (30 ft 10 in). They displaced 22,956 long tons (23,324 t) at normal load, and 24,729 long tons (25,126 t) at deep load.[2] They were provided with a complete double bottom and their hulls were subdivided by 23 longitudinal and transverse bulkheads. The ships had two rudders, both on the centerline. They had a crew of 31 officers and 969 enlisted men.[3]

Propulsion

The ships were fitted with three Parsons steam turbine sets, arranged in three engine rooms. The center engine room housed one set of turbines that drove the two inner propeller shafts. It was flanked by compartments on either side, each housing one turbine set powering the outer shafts. Steam for the turbines was provided by 20 Yarrow boilers, 8 of which burned oil and 12 of which burned coal sprayed with oil. Designed to reach a maximum speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) from 32,000 shaft horsepower (24,000 kW), neither of the ships reached this goal on their sea trials, only achieving speeds of 21 to 21.3 knots (38.9 to 39.4 km/h; 24.2 to 24.5 mph). The ships could store a maximum of 1,488 long tons (1,512 t) of coal and 886 long tons (900 t) of fuel oil that gave them a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

Armament

As built, the ships' main armament comprised thirteen 46-caliber 305-millimeter guns,[5] designed by Armstrong Whitworth and Vickers,[6] in five gun turrets. The turrets were all on the centerline, with a twin-gun turret superfiring over a triple-gun turret in fore and aft pairs, and a third triple turret amidships, designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X', and 'Y' from front to rear. The turrets had an elevation capability of −5 to +20 degrees and the ships could carry 88 rounds for each gun. Sources disagree regarding these guns' performance, but naval historian Giorgio Giorgerini says that they fired 452-kilogram (996 lb) armor-piercing (AP) projectiles at the rate of one round per minute and that they had a muzzle velocity of 840 m/s (2,800 ft/s), which gave a maximum range of 24,000 meters (26,000 yd).[7][Note 1]

The secondary armament on the two ships consisted of sixteen 45-caliber 152-millimeter (6 in) guns, also designed by Armstrong Whitworth,[9] mounted in casemates on the sides of the hull underneath the main guns. Their positions tended to be wet in heavy seas, especially the rear guns. These guns could depress to −5 degrees and had a maximum elevation of +20 degrees; they had a rate of fire of six shots per minute. They could fire a 22.1-kilogram (49 lb) high-explosive projectile with a muzzle velocity of 830 meters per second (2,700 ft/s) to a maximum distance of 16,000 meters (17,000 yd). The ships carried 3,440 rounds for them. For defense against torpedo boats, the ships carried nineteen 50-caliber 76 mm (3.0 in) guns; they could be mounted in 39 different positions, including on the turret roofs and upper decks. These guns had the same range of elevation as the secondary guns, and their rate of fire was higher at 10 rounds per minute. They fired a 6-kilogram (13 lb) AP projectile with a muzzle velocity of 815 meters per second (2,670 ft/s) to a maximum distance of 9,100 meters (10,000 yd). The ships were also fitted with three submerged 45-centimeter (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.[10]

Armor

The Andrea Doria-class ships had a complete waterline armor belt with a maximum thickness of 250 millimeters (9.8 in) that reduced to 130 millimeters (5.1 in) towards the stern and 80 millimeters (3.1 in) towards the bow.[11] Above the main belt was a strake of armor 220 millimeters (8.7 in) thick that extended up to the lower edge of the main deck. Above this strake was a thinner one, 130 millimeters thick, that protected the casemates. The ships had two armored decks: the main deck was 24 mm (0.94 in) thick in two layers on the flat that increased to 40 millimeters (1.6 in) on the slopes that connected it to the main belt. The second deck was 29 millimeters (1.1 in) thick, also in two layers. Fore and aft transverse bulkheads connected the belt to the decks.[12]

The frontal protection of the gun turrets was 280 millimeters (11.0 in) in thickness with 240-millimeter (9.4 in) thick sides, and an 85-millimeter (3.3 in) roof and rear. Their barbettes had 230-millimeter (9.1 in) armor above the deck that reduced to 180 millimeters (7.1 in) between the forecastle and upper decks and 130 millimeters below the upper deck. The forward conning tower had walls 320 millimeters (12.6 in) thick; those of the aft conning tower were 160 millimeters (6.3 in) thick.[12]

Modifications and reconstruction

During World War I, a pair of 50-caliber 76-millimeter guns on high-angle mounts were fitted as anti-aircraft (AA) guns, one gun at the bow and the other on top of 'X' turret. In 1925 the number of 50-caliber 76-millimeter guns was reduced to 13, all mounted on the turret tops, and six new 40-caliber 76-millimeter guns were installed abreast the aft funnel. Two license-built 2-pounder AA guns were also fitted. In 1926 the rangefinders were upgraded and a fixed aircraft catapult was mounted on the port side of the forecastle for a Macchi M.18 seaplane.[13]

By the early 1930s, the Regia Marina had begun design work on the new Littorio-class battleships, but it recognized that they would not be complete for some time. As a stop-gap measure in response to the new French Dunkerque-class battleships, the navy decided to modernize its old battleships; work on the two surviving Conte di Cavours began in 1933 and the two Andrea Dorias followed in 1937.[14] The work lasted until July 1940 for Duilio and October 1940 for Andrea Doria. The existing bow was dismantled and a new, longer, bow section was built, which increased their overall length by 10.91 meters (35 ft 10 in) to 186.9 meters (613 ft 2 in) (on the Cavour-class the new bow had been grafted over the existing one, instead). Their beam increased to 28.03 meters (92 ft 0 in)[15] and their draft at deep load increased to 10.3 meters (33 ft 10 in).[16] The changes made during their reconstruction increased their displacement to 28,882 long tons (29,345 t) for Andrea Doria and 29,391 long tons (29,863 t) for Duilio at deep load.[11] The ships' crews increased to 70 officers and 1,450 enlisted men.[16]

Two of the propeller shafts were removed and the existing turbines were replaced by two sets of Belluzzo geared steam turbines rated at 75,000 shp (56,000 kW). The boilers were replaced by eight superheated Yarrow boilers. On their sea trials the ships reached a speed of 26.9–27 knots (49.8–50.0 km/h; 31.0–31.1 mph), although their maximum speed was about 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) in service. The ships now carried 2,530 long tons (2,570 t) of fuel oil, which provided them with a range of 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at a speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).[16]

The center turret and the torpedo tubes were removed and all of the existing secondary armament and AA guns were replaced by a dozen 135-millimeter (5.3 in) guns in four triple-gun turrets and ten 90-millimeter (3.5 in) AA guns in single turrets. In addition the ships were fitted with fifteen 54-caliber Breda 37-millimeter (1.5 in) light AA guns in six twin-gun and three single mounts and sixteen 20-millimeter (0.8 in) Breda Model 35 AA guns, also in twin mounts. The 305-millimeter guns were bored out to 320 millimeters (13 in) and their turrets were modified to use electric power. They had a fixed loading angle of +12 degrees, but there is uncertainty on their new maximum elevation, with some sources citing a maximum value of +27 degrees,[17] while others claim one of +30 degrees.[18] The 320-millimeter AP shells weighed 525 kilograms (1,157 lb) and had a maximum range of 28,600 meters (31,300 yd) with a muzzle velocity of 830 m/s (2,700 ft/s).[19] In early 1942 the rearmost 20-millimeter mounts were replaced by twin 37-millimeter gun mounts and the 20-millimeter guns were moved to the roof of Turret 'B', while the RPC motors from the stabilized mounts of the 90 mm guns were removed[20][21] The forward superstructure was rebuilt with a new forward conning tower, protected with 260-millimeter (10.2 in) thick armor. Atop the conning tower there was a fire-control director fitted with three large rangefinders.[16]

The deck armor was increased during reconstruction to a total of 135 millimeters (5.3 in). The armor protecting the secondary turrets was 120 millimeters (4.7 in) thick.[16] The existing underwater protection was replaced by the Pugliese system that consisted of a large cylinder surrounded by fuel oil or water that was intended to absorb the blast of a torpedo warhead.[22]

These modernizations have been criticized by some naval historians, given that not only these ships would eventually prove to be inferior to the British battleships they were meant to face (namely the Queen Elizabeth-class), since by the time the decision to proceed was taken a war between Italy and the United Kingdom seemed more likely, but also because the cost of the reconstruction would be not much less than the cost of building a brand new Littorio-class battleship; moreover, the reconstruction work caused bottlenecks in the providing of steel plates, that caused substantial delays in the construction of the modern battleships, which otherwise might have been completed at an earlier date.[23]

Ships

| Ship | Namesake | Builder[5] | Laid down[5] | Launched[5] | Completed[2] | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrea Doria | Admiral Andrea Doria[24] | La Spezia Arsenale, La Spezia | 24 March 1912 | 30 March 1913 | 13 March 1916 | Scrapped, 1961[24] |

| Caio Duilio | Gaius Duilius[25] | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia, Castellammare di Stabia | 24 February 1912 | 24 April 1913 | 10 May 1915 | Scrapped, 1957[26] |

Service history

Both battleships were completed after Italy entered World War I on the side of the Triple Entente, though neither saw action, since Italy's principal naval opponent, the Austro-Hungarian Navy, largely remained in port for the duration of the war.[20] Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, the Italian naval chief of staff, believed that Austro-Hungarian submarines and minelayers could operate effectively in the narrow waters of the Adriatic.[27] The threat from these underwater weapons to his capital ships was too serious for him to use the fleet in an active way.[27] Instead, Revel decided to implement a blockade at the relatively safer southern end of the Adriatic with the battle fleet, while smaller vessels, such as the MAS torpedo boats, conducted raids on Austro-Hungarian ships and installations. Meanwhile, Revel's battleships would be preserved to confront the Austro-Hungarian battle fleet in the event that it sought a decisive engagement.[28]

Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio both cruised in the eastern Mediterranean after the war, and both were involved in postwar disputes over control of various cities. Caio Duilio was sent to provide a show of force during a dispute over control of İzmir in April 1919 and Andrea Doria assisted in the suppression of Gabriele D'Annunzio's seizure of Fiume in November 1920. Caio Duilio cruised the Black Sea after the İzmir affair until she was replaced in 1920 by the battleship Giulio Cesare. Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio were present during the Corfu incident in 1923 as part of the naval demonstration protesting the murder of General Enrico Tellini and four other Italians. In January 1925, Andrea Doria visited Lisbon, Portugal, to represent Italy during the celebration marking the 400th anniversary of the death of explorer Vasco da Gama. The two ships performed the normal routine of peacetime cruises and goodwill visits throughout the 1920s and early 1930s; both were placed in reserve in 1933.[29]

Both Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio went into drydock in the late 1930s for extensive modernizations; this work lasted until October and April 1940, respectively. By that time, Italy had entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers. The two ships joined the 5th Division based at Taranto. Caio Duilio participated in a patrol intended to catch the British battleship HMS Valiant and a convoy bound for Malta, but neither target was found. She and Andrea Doria were present during the British attack on Taranto on the night of 11/12 November 1940. A force of twenty-one Fairey Swordfish torpedo-bombers, launched from HMS Illustrious, attacked the ships moored in the harbor. Andrea Doria was undamaged in the raid, but Caio Duilio was hit by a torpedo on her starboard side. She was grounded to prevent her from sinking in the harbor and temporary repairs were effected to allow her to travel to Genoa for permanent repairs, which began in January 1941.[30][31] In February, she was attacked by the British Force H; several warships attempted to shell Caio Duilio while she was in dock, but they scored no hits.[32] Repair work lasted until May 1941, when she rejoined the fleet at Taranto.[33]

In the meantime, Andrea Doria participated in several operations intended to catch British convoys in the Mediterranean, including the Operation Excess convoys in January 1941. By the end of the year, both battleships were tasked with escorting convoys from Italy to North Africa to support the Italian and German forces fighting there. These convoys included Operation M41 on 13 December and Operation M42 on 17–19 December. During the latter, Andrea Doria and Giulio Cesare engaged British cruisers and destroyers in the First Battle of Sirte on the first day of the operation. Neither the Italians nor the British pressed their attacks and the battle ended inconclusively. Caio Duilio was assigned to distant support for the operation, and was too far away to actively participate in the battle. Convoy escort work continued into early 1942, but thereafter the fleet began to suffer from a severe shortage of fuel, which kept the ships in port for the next two years.[30] Caio Duilio sailed away from Taranto on 14 February with a pair of light cruisers and seven destroyers in order to intercept the British convoy MW 9, bounded from Alexandria to Malta, but the force could not locate the British ships, and so returned to port. After learning of Caio Duilio departure, however, British escorts scuttled the transport Rowallan Castle, previously disabled by German aircraft.[34]

Both ships were interned at Malta following Italy's surrender on 3 September 1943. They remained there until 1944, when the Allies allowed them to return to Italian ports; Andrea Doria went to Syracuse, Sicily, and Caio Duilio returned to Taranto before joining her sister at Syracuse. Italy was allowed to retain the two ships after the end of the war, and they alternated in the role of fleet flagship until 1953, when they were both removed from service. Andrea Doria carried on as a gunnery training ship, but Caio Duilio was simply placed in reserve. Both battleships were stricken from the naval register in September 1956 and were subsequently broken up for scrap.[35][36]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Giorgerini, p. 278

- 1 2 Gardiner & Gray, p. 260

- ↑ Giorgerini, pp. 270, 272

- ↑ Giorgerini, pp. 272–73, 278

- 1 2 3 4 Preston, p. 179

- ↑ Friedman, p. 234

- ↑ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 276, 278

- ↑ Friedman, pp. 233–34

- ↑ Friedman, p. 240

- ↑ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 277–78

- 1 2 Whitley, p. 162

- 1 2 Giorgerini, p. 271

- ↑ Whitley, p. 164

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin, p. 379

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 162, 164

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brescia, p. 62

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 158, 164–65

- ↑ Campbell, p. 324

- ↑ Campbell, p. 322

- 1 2 Whitley, p. 165

- ↑ Campbell, p. 343

- ↑ Whitley, p. 158

- ↑ De Toro, Augusto. "DALLE "LITTORIO" ALLE "IMPERO" - Navi da battaglia, studi e programmi navali in Italia nella seconda metà degli anni Trenta" (PDF). Marina Militare. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- 1 2 Silverstone, p. 294

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 297

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 296

- 1 2 Halpern, p. 150

- ↑ Halpern, pp. 141–42

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 165–67

- 1 2 Whitley, pp. 166–68

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 47

- ↑ Ireland, p. 64

- ↑ Whitley, p. 166

- ↑ Woodman, pp. 285–286

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 167–68

- ↑ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 284

References

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-913-8.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Giorgerini, Giorgio (1980). "The Cavour & Duilio Class Battleships". In Roberts, John. Warship IV. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 267–79. ISBN 0-85177-205-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Ireland, Bernard (2004). War in the Mediterranean 1940–1943. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-84415-047-X.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

- Woodman, Richard (2000). Malta Convoys 1940-1943. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6408-5.

Further reading

- Cernuschi, Ernesto; O'Hara, Vincent P. (2010). "Taranto: The Raid and the Aftermath". In Jordan, John. Warship 2010. London: Conway. pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0105-3.

- Stille, Mark (2011). Italian Battleships of World War II. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-831-2.

External links

Media related to Andrea Doria-class battleship at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Andrea Doria-class battleship at Wikimedia Commons