Art in modern Scotland

Art in modern Scotland includes all aspects of the visual arts in the country since the beginning of the twentieth century. In the early twentieth century, the art scene was dominated by the work of the members of the Glasgow School known as the Four, led Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who gained an international reputation for their combination of Celtic revival, Art and Crafts and Art Nouveau. They were followed by the Scottish Colourists and the Edinburgh School. There was a growing interest in forms of Modernism, with William Johnstone helping to develop the concept of a Scottish Renaissance. In the post-war period, major artists, including John Bellany and Alexander Moffat, pursued a strand of "Scottish realism". Moffat's influence can be seen in the work of the "new Glasgow Boys" from the late twentieth century. In the twenty-first century Scotland has continued to produce influential artists such as Douglas Gordon and Susan Philipsz.

Scotland possess significant collections of art, like the National Gallery of Scotland and National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the Burrell Collection and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. Prominent schools of art include the Edinburgh College of Art and the Glasgow School of Art. The major funding body with responsibility for the arts in the country is Creative Scotland. Support is also provided by local councils and independent foundations.

Early twentieth century

Glasgow School

For the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, developments in Scottish art are associated with the Glasgow School, a term that is used for a number of loose groups based around the city. The most important grouping, active from about 1890 and known as "The Four" or the "Spook School", was composed of acclaimed architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928), his wife the painter and glass artist Margaret MacDonald (1865–1933), her sister the artist Frances (1873–1921), and her husband, the artist and teacher Herbert MacNair (1868–1955). They produced a distinctive blend of influences, including the Celtic Revival, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and Japonisme, which found favour throughout the modern art world of continental Europe and helped define the Art Nouveau style.[1]

Scottish Colourists

The first significant group of Scottish artists to emerge in the twentieth century were the Scottish Colourists in the 1920s. The name was retrosepctively given to John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961), Francis Cadell (1883–1937), Samuel Peploe (1871–1935) and Leslie Hunter (1877–1931).[2] They knew each other and exhibited together, but did not form a cohesive group. All had spent time in France between 1900 and 1914[3] and looked for inspiration to Paris, particularly to the Fauvists, such as Monet, Matisse and Cézanne, whose techniques they combined with the painting traditions of Scotland.[4] They have been described as the first Scottish modern artists and were the major mechanism by which post-impressionism reached Scotland. Fergusson in particular would later be a major influence on bringing modernism to Scottish art.[3]

Edinburgh School

The group of artists connected with Edinburgh, most of whom had studied at Edinburgh College of Art during or soon after the First World War, became known as the Edinburgh School,[5] many of whom belonged to the informal 1922 Group.[6] They were influenced by French painters and the St. Ives School.[7] Their art was characterised by use of vivid and often non-naturalistic colour and the use of bold technique above form.[5] Members included William Gillies (1898–1973), who focused on landscapes and still life, John Maxwell (1905–62) who created both landscapes and studies of imaginative subjects, William Geissler (1894-1963),[8][9] watercolourist of landscapes in Perthshire, East Lothian and Hampshire,[10][11] William Crozier (1893–1930), whose landscapes were created with glowing colours, William MacTaggart (1903–81), noted for his landscapes of East Lothian, France and Norway[5] and Anne Redpath (1895–1965), best known for her two dimensional depictions of everyday objects.[12]

Modernism and the Scottish Renaissance

The philosopher, sociologist, town planner and writer Patrick Geddes (1854–1932) coined the phrase Scottish Renaissance in his magazine Evergreen. He argued that technological development needed to be in parallel with the arts. These ideas were taken up by a new generation, led by the poet Hugh MacDiarmid who argued for a synergy between science and art, the introduction of modernism into art and the creation of a distinctive national art. These ideas were expressed in art in the inter-war period by figures including Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976), William McCance (1894–1970), William Johnstone (1897–1981) and Fergusson.[13] Stanley Cursiter was influenced by the Celtic revival, post-impressionism and Futurism, as can be seen in his Rain on Princess Street (1913) and Regatta (1913). He went on to be a major painter of the coastline of this native Orkney, director of the National Gallery of Scotland and proposed the creation of a National Gallery of Modern Art in 1930.[14][15] Fergusson was one of the few British artists who could claim to have played a part in the creation of modernism and probably played a major part in the formulation of MacDiarmid's thought. His interest in machine imagery can be seen in paintings like Damaged Destroyer (1918). He co-operated with MacDiarmid on the journal Scottish Art and Letters and MacDiarmid quoted extensively from his work.[16]

William McCance's early work was in a bold post-impressionist style. After the First World War he moved to London with his wife, fellow student Agnes Miller Parker (1895–1980), where he joined the same circles as Fergusson, vorticist Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957) and nationalist composer Francis George Scott. Under these influences his work became increasingly abstract and influenced by vorticism, as can be seen in Women on an Elevator (1925) and The Engineer and his Wife (1925).[17] William Johnstone (1897–1981) was a cousin of F. G. Scott and met MacDiarmid as a student at Edinburgh. He studied cubism, surrealism and was introduced to new American art by his wife the sculptor Flora Macdonald. He moved towards abstraction, attempting to utilise aspects of landscape, poetry and Celtic art. His most significant work, A Point in Time (1929–38), has been described by art historian Duncan Macmillan as "one of the most important Scottish pictures of the century and one of the most remarkable pictures by any British painter in the period".[14][18][19]

Other artists influenced by modernism included James McIntosh Patrick (1907–98) and Edward Baird (1904–49).[14] Both trained in Glasgow, but spent most of their careers in and around their respective native cities of Dundee and Montrose. Both were influenced by surrealism and the work of Bruegel. They focused on landscape, as can be seen in McIntosh Patrick's Traquair House (1938) and more overtly Baird's The Birth of Venus (1934). Before his success in painting, McIntosh Patrick gained a reputation as an etcher. Leading figures in the field in the inter-war period included William Wilson (1905–72) and Ian Fleming (1906–94).[20]

New Scottish Group

The longest surviving member of the Scottish Colourists, Fergusson, returned to Scotland from France in 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, where he became a leading figure of a group of Glasgow artists. Members of Fergusson's group formed the New Art Club in 1940, in opposition to the established Glasgow Art Club. In 1942 they held the first exhibition of their own exhibiting society, the New Scottish Group, with Fergusson as its first president.[21]

The group had no single style, but shared left-wing tendencies and included artists influenced by trends in contemporary continental art. Painters involved included Donald Bain (1904–79), who was influenced by expressionism. William Crosbie (1915–99) was strongly influenced by surrealism. Marie de Banzie (1918–90), was influenced by expressionism and particularity post-expressionist Gauguin. Isabel Babianska (b. 1920), was influenced by expressionist Chaim Soutine. Expressionism can also be seen as an influence on the work of Millie Frood (1900–88), which included vivid colours and brushwork reminiscent of Van Gogh. Frood's urban scenes contain an element of social commentary and realism, influenced by Polish refugees Josef Herman (1911–2000), who was resident in Glasgow between 1940 and 1943[22] and Jankel Adler (1895–1949) who was in Kirkudbright from 1941–43.[23] Also influenced by Herman were husband and wife Tom MacDonald (1914–85) and Bet Low (1924–2007), who with painter William Senior (b. 1927) formed the Clyde Group, aimed at promoting political art. Their work included industrial and urban landscapes such as MacDonald's Transport Depot (1944–45) and Bet Low's Blochairn Steelworks (c. 1946).[22]

Photography

In the early twentieth century notable photographic work in Scotland included that of visiting artists, such as Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966), whose produced illustrations for the work of Robert Louis Stevenson and Paul Strand (1890–1976), as well as atmospheric depictions of Hebridean landscapes. There was also the record of the Gorbals in Glasgow made by Bert Hardy (1913–95), Joseph MacKenzie (b. 1929) and Oscar Marzaroli (1933–88), but, having pioneered photography in the late nineteenth century, the artistic attainment of native photographers was not high in the early twentieth century.[24]

Later twentieth century to the present

Post-war artists

Notable post-war artists included Robin Philipson (1916–92), who was influenced by the Colourists, but also Pop Art and neo-Romanticism.[25] Robert MacBryde (1913–66), Robert Colquhoun (1914–64) and Joan Eardley (1921–63), were all graduates of the Glasgow School of Art. MacBryde and Colquhoun were influenced by neo-Romanticism and the Cubism of Adler. The English-born Eardley moved to Glasgow and explored the landscapes of Kincardineshire coast and created depictions of Glasgow tenements and children in the streets.[26] Scottish artists that continued the tradition of landscape painting and joined the new generation of modernist artists of the St Ives School were Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) and Margaret Mellis (1914–2009).[27]

Paris continued to be a major destination for Scottish artists, with William Gear (1916–97) and Stephen Gilbert (1910–2007) encountering the linear abstract painting of the avant-garde COBRA group there in the 1940s. Their work was highly coloured and violent in execution.[28] Also a visitor to Paris was Alan Davie (b. 1920-2014),[29] who was influenced by jazz and Zen Buddhism, and moved further into abstract expressionism.[14] Ian Hamilton Finlay's (1925–2006) work explored the boundaries between sculpture, print making, literature (especially concrete poetry) and landscape architecture. His most ambitious work, the garden of Little Sparta opened in 1960.[30]

Scottish Realism and the Glasgow Pups

John Bellany (1942–2013), mainly focusing on the coastal communities of his birth, and Alexander Moffat (b. 1943), who concentrated on portraiture, grouped under the description of "Scottish Realism", were among the leading Scottish intellectuals from the 1960s.[31] The artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, sometimes known as the "new Glasgow Boys", or "Glasgow pups", were associated with Moffat and the Glasgow School of Art.[32] They included Steven Campbell (1953–2007), Peter Howson (b. 1958), Ken Currie (b. 1960) and Adrian Wisniewski (b. 1958). Their figurative work had a comic book-like quality and put an emphasis on social commentary.[33] Campbell and Wisniewski's post-modern painting adopted a whimsical approach to history. Campbell often employed figures reminiscent of characters from 1930s novels confronted by the disorder and confusion of the real world, as in his Young Men in Search of Simplicity (1989).[34] Currie revived historical painting devoted to the socialist history of Glasgow in a series of paintings for the People's Palace in 1987. Currie also approached the problems of historical painting through his series of prints The Saracen Heads (1988).[35] A parallel movement in Edinburgh, focused around the 369 Gallery in the city, included Caroline McNairn (b. 1955–2010), Robert Maclaurin (b. 1965) and Gwen Hardie (b. 1962).[36]

Sculpture

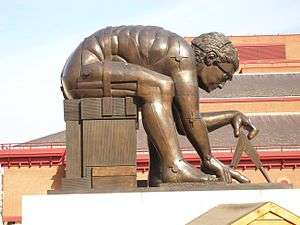

The sculpture of Eric Schilsky (1898–1974) and Hew Lorimer (1907–93) was in the existing tradition of modelling and carving.[7] In contrast sculptor and artist Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005) was a pioneer of pop art and in a varied career produced many works that examined juxtapositions between fantasy and the modern world.[12] New sources of direct government arts funding encouraged greater experimentation among a new generation of sculptors that incorporated aspects of modernism, such as Jake Harvey (b. 1948), Doug Cocker (b. 1945), Ainslie Yule (b. 1941) and Gavin Scobie (1940–2012).[7] In contrast Sandy Stoddart (b. 1959) works primarily on "nationalist" figurative sculpture in clay within the neoclassical tradition. He is best known for his civic monuments, including 10 feet (3.0 m) bronze statues of the philosophers David Hume and Adam Smith, on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh.[37]

Photographic renaissance

In the late twentieth century, photography in Scotland enjoyed a renaissance, encouraged by figures including Richard Hough (1945–85) who founded the Stills Gallery for photography in Edinburgh in 1977 and Murray Johnston (1949–90), who was its director (1982–86).[38] Notable practitioners in Scotland included the American Thomas Joshua Cooper (b. 1946).[24] More recent exponents who have received acclaim include Pradip Malde (b. 1957), Maud Sulter (1960–2008) and Owen Logan (b. 1963).[24]

Contemporary artists

Since the 1990s, the most commercially successful artist has been Jack Vettriano (b. 1959), whose work usually consists of figure compositions, with his most famous painting The Singing Butler (1992), often cited as the best selling print in Britain. However, he has received little acclaim from critics.[39] Contemporary artists emerging from Glasgow and Dundee include David Mach (b. 1960), working in the medium of installation art,[40] Richard Wright (b. 1960), noted for his intricate wall paintings, James Lambie (b. 1965) who specialises in colourful sculptural installations[41] and Susan Philipsz (b. 1965) who works in sound installations.[42] A group that emerged from Glasgow School of Art in the early 1990s, and later described as "The Irascibles", includes Roderick Buchanan (b. 1965), who works in installations, film and photography, Douglas Gordon (b. 1966) working in video art, Christine Borland (1965), whose work focuses on forensic science, and sculptor Martin Boyce (b. 1967).[43] In the generation of more recent artists Lucy McKenzie's (b. 1977) painting is often sexually explicit,[44] while Sandy Smith (b. 1983) has produced installation art that combines video and landscape art.[45]

Institutions

Art museums and galleries

Major art galleries in Edinburgh include the National Gallery of Scotland, which has a collection of national and international art. The National Museum of Scotland was formed by the merger of the Royal Museum of Scotland and the National Museum of Antiquities and includes items from the decorative arts, ethnography and archaeology. The Scottish National Portrait Gallery has portraits of major national figures. The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, houses the national collection of twentieth-century Scottish and international art. The Dean Gallery houses the Gallery of Modern Art's collection of Dada and Surreal art.[46] The Talbot Rice Gallery houses both old masters and contemporary Scottish works.[47]

Glasgow galleries include the Burrell Collection, housing the extensive and eclectic collection of art left to the city by shipping magnate Sir William Burrell. The Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum houses a collection of international art and products of the Glasgow School. The Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery houses sixty works by James McNeil Whistler and works by Mackintosh, as well as an international collection of masters from the seventeenth century onwards.[48] Other major collections include the Aberdeen Art Gallery, which houses a major collection of British and international art[49] and Dundee Contemporary Arts, which houses two contemporary art galleries.[50] An attempt to found a Scottish National Photography Centre in Edinburgh at the beginning of the 2000s failed, but the National Portrait Gallery, refurbished in 2011 now contains a dedicated permanent photographic gallery[51] and photography is represented in the Stills and Portfolio Galleries in Edinburgh and at Streetlevel Photoworks in Glasgow.[24]

Art schools and colleges

Scotland has had schools of art since the eighteenth century, many of which continue to exist in different forms today. Edinburgh College of Art developed from the Trustees Academy, founded in the city in 1760, and was established in its current form in 1907. After a long independent history, in 2011 it became part of the University of Edinburgh.[52] Glasgow School of Art grew from the city's School of Design, founded in 1845. Grays School of Art in Aberdeen was founded in 1885. Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design was founded in Dundee in 1909.[53] There are also smaller private institutions such as the Leith School of Art founded in a former Lutheran church in 1988.[54] Photography is represented by courses at the major colleges of art and universities.[24]

Organisations

Creative Scotland is the national agency for the development of the arts in Scotland. It superseded the Scottish Arts Council, which was formed in 1994 following a restructuring of the Arts Council of Great Britain, but had existed as an autonomous body since a royal charter of 1967.[55][56] In addition, some local authorities and private interests have supported to the arts, although this has been more limited since local government reorganisation in 1996.[57] Independent arts foundations that promote the visual arts include the Royal Scottish Academy, founded in 1826 and granted a Royal Charter in 1837.[58] Photography is promoted by the Scottish Society for the History of Photography.[24]

References

Notes

- ↑ S. Tschudi-Madsen, The Art Nouveau Style: a Comprehensive Guide (Mineola, NY: Courier Dover, 2002), ISBN 0-486-41794-8, pp. 283–4.

- ↑ "The Scottish Colourists", Visit Scotland.com, archived from the original on 29 April 2008, retrieved 7 May 2010

- 1 2 I. Chilvers, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 0-19-953294-X, p. 575.

- ↑ "The Scottish Colourists", Explore Art, archived from the original on 12 November 2012, retrieved 12 November 2012

- 1 2 3 "The Edinburgh School", Edinburgh Museums and Galleries, retrieved 10 April 2013

- ↑ http://www.artbiogs.co.uk/2/societies/1922-group, retrieved 7 October 2015

- 1 2 3 D. Macmillan, "Culture: modern times 1914–: art", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 153–4.

- ↑ http://www.s-s-a.org/presidents-and-secretaries/

- ↑ http://www.rsw.org.uk/pages/past_members.php?pageNum_rsPastMembers=10&totalRows_rsPastMembers=313

- ↑ The Life and Art of William Geissler (1894-1963): Norman Shaw, MPhil Thesis, Edinburgh College of Art, 1994

- ↑ The Art of William Geissler 1894-1963, Poetry of Place, Author: Alistair (Introduction) Rowan, Publisher: Edinburgh College of Art, 1996

- 1 2 L. A. Rose, M. Macaroon, V. Crow, Frommer's Scotland (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 12th edn., 2012), ISBN 1-119-99276-1, p. 25.

- ↑ D. Macmillan, Scottish Art 1460–1990 (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1990), ISBN 0500203334, p. 348.

- 1 2 3 4 M. Gardiner, Modern Scottish Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-7486-2027-3, p. 173.

- ↑ M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, pp. 163–4.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art , p. 350.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art, pp. 348–50.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art, pp. 351–2.

- ↑ D. Macmillan, "Review: Painters in Parallel: William Johnstone & William Gillies", Scotsman.com, 19 January 2012, retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, pp. 175–6.

- ↑ D. Macmillan, Scottish Art in the 20th century, 1890–2001 (Mainstream, 2001), p. 80.

- 1 2 D. Macmillan, Scottish Art, 1460–1990 (Mainstream, 1990), ISBN 1851582517, pp. 370–1.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 D. Burn, "Photography", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 476–7.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, pp. 189–90.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, pp. 191–2.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, p. 193.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art, p. 376.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, p. 194.

- ↑ K. Johnson (31 March 2006), "Ian Hamilton Finlay, 80, poet and conceptual artist, dies", The New York Times, archived from the original on 26 September 2012

- ↑ C. Richardson, Scottish Art Since 1960: Historical Reflections and Contemporary Overviews (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), ISBN 0-7546-6124-5, p. 58.

- ↑ Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, p. 255.

- ↑ D. Reid, The Rough Guide to Edinburgh (London: Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 1-85828-887-8, p. 114.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art, p. 405.

- ↑ Macmillan, Scottish Art, p. 406.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scottish Art, p. 212.

- ↑ C. Aslet, "Alexander Stoddart: talking statues" The Daily Telegraph, retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ↑ C. Henry, "Scots photography loses a champion", Glasgow Herald, 6 January 1990, retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, p. 657.

- ↑ P. Küppers, The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performances And Contemporary Art (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), ISBN 0-8166-4653-8, p. 61.

- ↑ C. Richardson, Scottish Art Since 1960: Historical Reflections and Contemporary Overviews (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), ISBN 0-7546-6124-5, p. 177.

- ↑ C. Higgins (17 October 2011), "Glasgow's Turner connection", guardian.co.uk, archived from the original on 9 May 2012

- ↑ N. Mulholland, The Cultural Devolution: Art in Britain in the Late Twentieth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003) ISBN 0-7546-0392-X, p. 144.

- ↑ S. Thornton, Seven Days in the Art World (Granta, 2012), ISBN 1-84708-693-4.

- ↑ G. Wichert, "The Object Moved by Its Own Success", 15 Bytes, 17 October 2008, retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ↑ D. Porter, and D. Prince, Frommer's Scotland (John Wiley & Sons, 10th edn., 2008), ISBN 0470249129, pp. 109–111.

- ↑ N. Wilson, Edinburgh Encounter 2 (Lonely Planet, 2nd edn., 2011), ISBN 1741794757, p. 47.

- ↑ Porter, and Prince, Frommer's Scotland, pp. 191–4.

- ↑ Porter, and Prince, Frommer's Scotland, p. 282.

- ↑ N. Wilson and A. Murphy, Scotland (Lonely Planet, 5th edn., 2010), ISBN 1742203744, p. 235.

- ↑ R. Simpson, The Photography of Victorian Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), ISBN 0748654615, pp. 192–4.

- ↑ Edinburgh College of Art guide, The Telegraph, 20 June 2011, retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ D. Arnold and D. P. Corbett, A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), ISBN 1118313771.

- ↑ G. Ramsden, Leith: Scotland's Independent Art School: Founders and Followers (Edinburgh: Stone Trough Books, 2009), ISBN 0954454227.

- ↑ M. Garber, Patronizing the Arts (Princeton University Press, 2008), ISBN 1400830036, pp. 55–6.

- ↑ R.-B. M. Quinn, Public Policy and the Arts: a Comparative Study of Great Britain and Ireland (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), ISBN 1840141743, p. 137.

- ↑ M. Chisholm, Structural Reform of British Local Government: Rhetoric and Reality (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), ISBN 071905771X, p. 141.

- ↑ Whitaker's Concise Almanack 2012 (A&C Black, 2011), ISBN 1408142309, p. 410.

Bibliography

- Arnold, D., and Corbett, D. P., A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), ISBN 1118313771.

- Aslet, C., "Alexander Stoddart: talking statues" The Daily Telegraph, retrieved 12 July 2008.

- Burn, D., "Photography", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056.

- Chilvers, I., ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 0-19-953294-X.

- Chisholm, M., Structural Reform of British Local Government: Rhetoric and Reality (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), ISBN 071905771X.

- Garber, M., Patronizing the Arts (Princeton University Press, 2008), ISBN 1400830036.

- Gardiner, M., Modern Scottish Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-7486-2027-3.

- Henry, C., "Scots photography loses a champion", Glasgow Herald, 6 January 1990, retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Küppers, P., The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performances And Contemporary Art (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), ISBN 0-8166-4653-8.

- MacDonald, M., Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334.

- Macmillan, D., "Culture: modern times 1914–: art", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056.

- Macmillan, D., Scottish Art 1460–1990 (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1990), ISBN 0500203334.

- Macmillan, D., "Review: Painters in Parallel: William Johnstone & William Gillies", Scotsman.com, 19 January 2012, retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Mulholland, N., The Cultural Devolution: Art in Britain in the Late Twentieth Century (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003) ISBN 0-7546-0392-X.

- Porter, D., and Prince, D., Frommer's Scotland (John Wiley & Sons, 10th edn., 2008), ISBN 0470249129.

- Quinn, R.-B. M., Public Policy and the Arts: a Comparative Study of Great Britain and Ireland (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), ISBN 1840141743.

- Ramsden, G., Leith: Scotland's Independent Art School: Founders and Followers (Edinburgh: Stone Trough Books, 2009), ISBN 0954454227.

- Reid, D., The Rough Guide to Edinburgh (London: Rough Guides, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 1-85828-887-8.

- Richardson, C., Scottish Art Since 1960: Historical Reflections and Contemporary Overviews (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), ISBN 0-7546-6124-5.

- Rose, L. A., Macaroon, M., Crow, V., Frommer's Scotland (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 12th edn., 2012), ISBN 1-119-99276-1.

- Simpson, R., The Photography of Victorian Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), ISBN 0748654615.

- Thornton, S., Seven Days in the Art World (Granta, 2012), ISBN 1-84708-693-4.

- Tschudi-Madsen, S., The Art Nouveau Style: a Comprehensive Guide (Mineola, NY: Courier Dover, 2002), ISBN 0-486-41794-8.

- Wichert, G., "The Object Moved by Its Own Success", 15 Bytes, 17 October 2008, retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Wilson, N., Edinburgh Encounter 2 (Lonely Planet, 2nd edn., 2011), ISBN 1741794757.

- Wilson, N., and Murphy, A., Scotland (Lonely Planet, 5th edn., 2010), ISBN 1742203744.

- Whitaker's Concise Almanack 2012 (A&C Black, 2011), ISBN 1408142309.