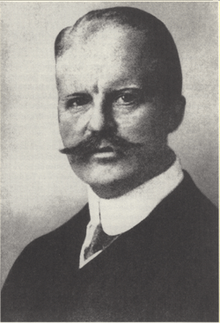

Arthur Zimmermann

Arthur Zimmermann (5 October 1864 – 6 June 1940) was State Secretary for Foreign Affairs of the German Empire from 22 November 1916 until his resignation on 6 August 1917. His name is associated with the Zimmermann Telegram during World War I. However, he was closely involved in plans to support an Irish rebellion, an Indian rebellion, and to help the Communists undermine Tsarist Russia.

Career

He was born in Marggrabowa, East Prussia, then in the Kingdom of Prussia (present-day Olecko, Mazury, Poland). He studied law from 1884-87 in Königsberg, East Prussia, and Leipzig. A period as a junior lawyer followed and later he received his doctorate of law. In 1893, he took up a career in diplomacy and entered the consular service in Berlin. He arrived in China in 1896 (Canton in 1898), and rose to the rank of consul in 1900. While stationed in the Far East, he witnessed the Boxer Rebellion in China. As part of his transfer to the Foreign Office, he returned to Germany in 1902. A portion of this trip was via railroad across the Continental United States, a fact he would later use to inflate his supposed expertise on the nation.[1]

Later he was called to the Foreign Office, became Under Secretary of State in 1911, and on 24 November 1916, he accepted his confirmation as Secretary of State, succeeding Gottlieb von Jagow in this position. Actually, he had assumed a large share of his superior's negotiations with foreign envoys for several years prior to his appointment because of von Jagow's reservedness in office. He was the first non-aristocrat to serve as foreign secretary.

Kronrat

As acting secretary Zimmerman took part in the so-called Kronrat, the deliberations in 1914, with Kaiser Wilhelm II and Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, in which the decision was taken to support Austria-Hungary after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria at Sarajevo, which ultimately was to lead to the outbreak of war. He later disavowed the name Kronrat since it was the Kaiser's opinion that was decisive in the discussion, but with which Bethmann-Hollweg and Zimmermann concurred.

Irish rebellion

In late 1914 Zimmermann was visited by Roger Casement, the Irish revolutionary. A plan was laid to land 25,000 soldiers in the west of Ireland with 75,000 rifles. However, the German general staff did not agree. In April 1916 Casement returned to Ireland in a U-boat and was captured and executed. A German ship (the Libau) renamed the Aud, flying Norwegian colours, shipped 20,000 rifles to the south Irish coast, but it failed to link up with the rebels and was scuttled. Planning on this support, a minority of the Irish Volunteers launched the Easter Rising in Dublin. Though the Rising failed, its political effect led on to the Anglo-Irish war in 1919–22 and the formation of the Irish Free State.

Resignation and Death

On 6 August 1917, Zimmermann resigned as foreign secretary and was succeeded by Richard von Kühlmann. One of the causes of his resignation was the famous Zimmermann Telegram he sent on 16 January 1917. He died in Berlin in 1940 of pneumonia.[2]

Zimmermann telegram and resignation

Background

Two and a half years into World War I, the United States had maintained a status of neutrality while the Allied armies had been fighting those of the Central Powers in the trenches of northern France and Belgium. Although President Woodrow Wilson had been re-elected – winning the election on the slogan, "He kept us out of the war" – it became increasingly difficult to maintain that position.[3]

After the Royal Navy had been engaged in a successful naval blockade against all German shipping for some time, the German Supreme High Command concluded that only a total submarine offensive would break the stranglehold. Although the decision was made on 9 January 1917, the Americans were uninformed of the operation until 31 January.[4]

The Germans abrogated their Sussex pledge (not to sink merchant ships without due warning and to save human lives wherever possible) and began an unrestricted U-boat campaign on February 1, 1917. Since it was obvious that US shipping would also come under attack in the course of this operation, it became just a matter of time before the USA was drawn into the conflict.

Germany had been pursuing various interests in Mexico from the beginning of the 20th century. Although a latecomer in the area, with Spain, Britain, and France having established themselves there centuries earlier, the Kaiser's Germany attempted to secure a continuing presence. This entailed many different approaches to the Mexican Republic and its changing, often revolutionary, governments as well as assuring the United States (most of the time) of Germany's peaceful intentions. German diplomacy in the area depended on sympathetic relations with the Mexican government of the day. Among the options discussed during Arthur Zimmermann's period in office was a German offer to improve communications between the two nations and a suggestion that Mexico purchase German submarines for its navy. After Francisco Villa's cross-border raids into New Mexico President Wilson sent a punitive expedition into Mexico to pursue the raiders.

This encouraged the Germans to believe (mistakenly) that this and other US concerns in the area would tie up US resources and military operations for some time to come, sufficiently to justify the overtures made by Arthur Zimmermann in his telegram to the Venustiano Carranza government. His proposals included an agreement for a German alliance with Mexico, while Germany would still try to maintain a state of neutrality with the United States. If this policy were to fail, the note suggested, the Mexican government should make common cause with Germany, try to persuade the Japanese government to join the new alliance, and attack the US. Germany for its part would promise financial assistance and the restoration of its former territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona to Mexico.[5]

Sending

Effect

On 24 February, the telegram was finally delivered to the US ambassador in Britain, Walter Hines Page, who two days later retransmitted it to President Wilson. On 1 March, the United States Government passed the text of the telegram to the press. At first, some sectors of the US papers, especially those of the Hearst press empire, questioned whether the telegram was a forgery made by British intelligence in an attempt to persuade the US government to enter the war on Britain's side. This opinion was reinforced by German and Mexican diplomats, as well as pro-German and pacifist opinion-formers in the United States. However, on 29 March 1917, Zimmermann gave a speech to the Reichstag confirming the text of the telegram and so put an end to all speculation as to its authenticity. By that time a number of US ships had been torpedoed with heavy loss of life.

On 2 April, President Wilson asked Congress to agree to declare war on Germany, citing, among other grievances, that Germany "means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors".[6] On 6 April, Congress approved the resolution for war by a wide margin, with the Senate voting 82 to 6 in favor.[7] The United States had entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

Arthur Zimmermann's speech

On 29 March 1917, Zimmerman delivered a speech intended to explain his side of the situation.[8] He began that he had not written a letter to Carranza but had given instructions to the German ambassador via a "route that had appeared to him to be a safe one".

He also said that despite the submarine offensive, he had hoped that the USA would remain neutral. His instructions (to the Mexican government) were only to be carried out after the US declared war, and he believed his instructions to be "absolutely loyal as regards the US". In fact, he blamed President Wilson for breaking off relations with Germany "with extraordinary roughness" after the telegram was received, and that therefore the German ambassador "no longer had the opportunity to explain the German attitude, and that the US government had declined to negotiate".

Mexico's reply

Later, a general assigned by Carranza to assess the realities of a Mexican takeover of their former provinces came to the conclusion that it would not work. Taking over the three states would almost certainly cause future problems and possibly war with the US; Mexico would also be unable to accommodate a large Anglo population within its borders; and Germany would not be able to supply the arms needed in the hostilities that would surely arise. Carranza declined Zimmermann's proposals on 14 April.

The fact-finding mission of Nuncio Pacelli

At the end of June 1917, Zimmermann found the first real opportunity for paving the way to peace negotiations during his period of administration. At several meetings with the Bavarian Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli (later to become Pope Pius XII) and Uditore Schioppa, who were on a fact-finding mission, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and Zimmermann outlined their plans.

There would be no annexations of territories, no border adjustments with Russia, Poland was to remain an independent state, all occupied areas of France and Belgium were to be evacuated, and Alsace-Lorraine would be ceded to France. The only exception in return was to be the restitution of all former German colonies to Germany. None of these plans came to fruition because neither of the two German participants would be very much longer in office. As an afterthought, it was Chancellor von Bethmann-Hollweg's belief – unlike that of the General Staff's – that once the United States entered the war, the prospects for Germany would indeed be bleak.

Peace in the East

In March 1917, with the imminent collapse of the Russian front, Zimmermann took steps to promote Peace in the East with the Russians, a proposal that was of immense importance to Germany at the time. The foreign secretary set forth the following: regulations for frontline contacts with the opposite side; reciprocal withdrawal of the occupied areas; an amicable agreement about Poland, Lithuania, and Kurland; and a promise to aid Russia in its reconstruction and rehabilitation. Last not least, Lenin and the émigré revolutionaries would be allowed to pass through Germany to Russia by train. These proposals once carried out, would free Germany's armies in the east and allow them to be concentrated in the west, a master-stroke that would reinforce the German western front vastly. Zimmermann thus contributed to the outcome of the October Revolution.

References

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2014) World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ABC-CLIO, pg. 1704

- ↑ "Arthur Zimmermann" Germany State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, WWI". Totallyhistory.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Woodrow Wilson: Speech of Acceptance". Presidency.ucsb.edu, 2 September 1916; retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Schmidt, Donald E. (2005). The Folly of War: American foreign policy, 1898–2005. Algora Publishing. pg. 83; ISBN 0-87586-383-3.

- ↑ "Arthur Zimmermann profile". Britannica.com. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Wilson's War Message to Congress - World War I Document Archive". Wwi.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Primary Documents - Arthur Zimmermann on the Zimmermann Telegram". First World War.com. 29 March 1917. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arthur Zimmermann. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Arthur Zimmermann. |

- The Zimmermann speech

- Japanese Prime Minister Count Terauchi on the Zimmermann Telegram

- Works by or about Arthur Zimmermann in libraries (WorldCat catalog)