Asylum in the United States

The United States recognizes the right of asylum of individuals as specified by international and federal law. A specified number of legally defined refugees, either apply for asylum from inside the U.S. or apply for refugee status from outside the U.S., are admitted annually. Refugees compose about one-tenth of the total annual immigration to the United States, though some large refugee populations are very prominent. Since World War II, more refugees have found homes in the U.S. than any other nation and more than two million refugees have arrived in the U.S. since 1980. In the years 2005 through 2007, the number of asylum seekers accepted into the U.S. was about 40,000 per year. This compared with about 30,000 per year in the UK and 25,000 in Canada. The U.S. accounted for about 10% of all asylum-seeker acceptances in the OECD countries in 1998-2007.[1] The United States is by far the most populous OECD country and when corrected for population it receives less than average: For example, in 2010-14 (before the massive migrant surge in Europe in 2015) it was positioned as 28 of 43 industrialized countries reviewed by UNHCR, after Canada, the Scandinavian coutries, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and others.[2]

Asylum has three basic requirements. First, an asylum applicant must establish that he or she fears persecution in their home country.[3] Second, the applicant must prove that he or she would be persecuted on account of one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, and social group. Third, an applicant must establish that the government is either involved in the persecution, or unable to control the conduct of private actors.

Character of refugee inflows and resettlement

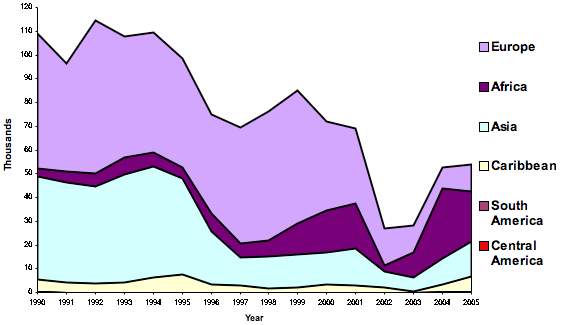

During the Cold War, and up until the mid-1990s, the majority of refugees resettled in the U.S. were people from the former-Soviet Union and Southeast Asia. The most conspicuous of the latter were the refugees from Vietnam following the Vietnam War, sometimes known as "boat people". Following the end of the Cold War, the largest resettled group were refugees from the Balkans, primarily Serbs, from Croatia and Bosnia who were fleeing their homes as a result of genocide perpertuated by Croatian army. (See Operation Storm). In the 2000s, the proportion of Africans rose in the annual resettled population, as many fled various ongoing conflicts.

Large metropolitan areas have been the destination of most resettlements, with 72% of all resettlements between 1983 and 2004 going to 30 locations. The historical gateways for resettled refugees have been California (specifically Los Angeles, Orange County, San Jose, and Sacramento), the Mid-Atlantic region (New York in particular), the Midwest (specifically Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis-St. Paul), and Northeast (Providence, Rhode Island). In the last decades of the twentieth century, Washington, D.C.; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; and Atlanta, Georgia provided new gateways for resettled refugees. Particular cities are also identified with some national groups: metropolitan Los Angeles received almost half of the resettled refugees from Iran, 20% of Iraqi refugees went to Detroit, and nearly one-third of refugees from the former Soviet Union were resettled in New York. These ethnic enclaves partially result from attempts by the agencies arranging resettlement to place newly arrived refugees with family members already in the U.S. and in locations where government agencies and charities are known to have staff that speak their language. Ethnic grouping also results as refugees and migrants seek out the comfort of familiar languages, food and customs.

Relevant law and procedures

The United States is obliged to recognize valid claims for asylum under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. As defined by these agreements, a refugee is a person who is outside his or her country of nationality (or place of habitual residence if stateless) who, owing to a fear of persecution on account of a protected ground, is unable or unwilling to avail himself of the protection of the state. Protected grounds include race, nationality, religion, political opinion and membership of a particular social group. The signatories to these agreements are further obliged not to return or "refoul" refugees to the place where they would face persecution.

This commitment was codified and expanded with the passing of the Refugee Act of 1980 by the United States Congress. Besides reiterating the definitions of the 1951 Convention and its Protocol, the Refugee Act provided for the establishment of an Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HSS) to help refugees begin their lives in the U.S. The structure and procedures evolved and by 2004, federal handling of refugee affairs was led by the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) of the U.S. Department of State, working with the ORR at HHS. Asylum claims are mainly the responsibility of the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Refugee quotas

Each year, the President of the United States sends a proposal to the Congress for the maximum number of refugees to be admitted into the country for the upcoming fiscal year, as specified under section 207(e) (1)-(7) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. This number, known as the "refugee ceiling", is the target of annual lobbying by both refugee advocates seeking to raise it and anti-immigration groups seeking to lower it. However, once proposed, the ceiling is normally accepted without substantial Congressional debate. The September 11, 2001 attacks resulted in a substantial disruption to the processing of resettlement claims with actual admissions falling to about 26,000 in fiscal year 2002. Claims were doublechecked for any suspicious activity and procedures were put in place to detect any possible terrorist infiltration, though some advocates noted that, given the ease with which foreigners can otherwise legally enter the U.S., entry as a refugee is comparatively unlikely. The actual number of admitted refugees rose in subsequent years with refugee ceiling for 2006 at 70,000. Critics note these levels are still among the lowest in 30 years.

| Recent actual, projected and proposed refugee admissions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Africa | East Asia | Europe and Central Asia | Latin America/Caribbean | Near East/South Asia | Unallocated reserve | Total |

| FY 2012 actual arrivals[4] | 10,608 | 14,366 | 1,129 | 2,078 | 30,057 | - | 58,238 |

| FY 2013 ceiling[4] | 12,000 | 17,000 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 31,000 | 3,000 | 70,000 |

| FY 2013 actual arrivals[5] | 15,980 | 16,537 | 580 | 4,439 | 32,389 | - | 69,925 |

| FY 2014 ceiling[5] | 15,000 | 14,000 | 1,000 | 5,000 | 33,000 | 2,000 | 70,000 |

| FY 2014 actual arrivals[6] | 17,476 | 14,784 | 959 | 4,318 | 32,450 | - | 69,987 |

| FY 2015 ceiling[6] | 17,000 | 13,000 | 1,000 | 4,000 | 33,000 | 2,000 | 70,000 |

| FY 2015 actual arrivals[7] | 22,472 | 18,469 | 2,363 | 2,050 | 24,579 | - | 69,933 |

| FY 2016 ceiling[7] | 25,000 | 13,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 | 34,000 | 6,000 | 85,000 |

| FY 2016 actual arrivals[8] | 31,625 | 12,518 | 3,957 | 1,340 | 35,555 | - | 84,995 |

| FY 2017 ceiling[9] | 35,000 | 12,000 | 4,000 | 5,000 | 40,000 | 14,000 | 110,000 |

A total of 73,293 persons were admitted to the United States as refugees during 2010. The leading countries of nationality for refugee admissions were Iraq (24.6%), Burma (22.8%), Bhutan (16.9%), Somalia (6.7%), Cuba (6.6%), Iran (4.8%), DR Congo (4.3%), Eritrea (3.5%), Vietnam (1.2%) and Ethiopia (0.9%).

Application for resettlement by refugees abroad

The majority of applications for resettlement to the United States are made to U.S. embassies in foreign countries and are reviewed by employees of the State Department. In these cases, refugee status has normally already been reviewed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and recognized by the host country. For these refugees, the U.S. has stated its preferred order of solutions are: (1) repatriation of refugees to their country of origin, (2) integration of the refugees into their country of asylum and, last, (3) resettlement to a third country, such as the U.S., when the first two options are not viable.

The United States prioritizes valid applications for resettlement into three levels. Priority One consists of:

persons facing compelling security concerns in countries of first asylum; persons in need of legal protection because of the danger of refoulement; those in danger due to threats of armed attack in an area where they are located; or persons who have experienced recent persecution because of their political, religious, or human rights activities (prisoners of conscience); women-at-risk; victims of torture or violence, physically or mentally disabled persons; persons in urgent need of medical treatment not available in the first asylum country; and persons for whom other durable solutions are not feasible and whose status in the place of asylum does not present a satisfactory long-term solution. -UNHCR Resettlement Handbook

Priority Two is composed of groups designated by the U.S. government as being of special concern. These are often identified by an act proposed by a Congressional representative. Priority Two groups proposed for 2008 included:[10]

- "Jews, Evangelical Christians, and Ukrainian Catholic and Orthodox religious activists in the former Soviet Union, with close family in the United States" (sponsored by Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.))

- from Cuba: "human rights activists, members of persecuted religious minorities, former political prisoners, forced-labor conscripts (1965-68), persons deprived of their professional credentials or subjected to other disproportionately harsh or discriminatory treatment resulting from their perceived or actual political or religious beliefs or activities, and persons who have experienced or fear harm because of their relationship – family or social – to someone who falls under one of the preceding categories"

- from Vietnam: "the remaining active cases eligible under the former Orderly Departure Program (ODP) and Resettlement Opportunity for Vietnamese Returnees (ROVR) programs"; individuals who, through no fault of their own, were unable to access the ODP program before its cutoff date; and Amerasian citizens, who are counted as refugee admissions

- individuals who have fled Burma and who are registered in nine refugee camps along the Thai/Burma border and who are identified by UNHCR as in need of resettlement

- UNHCR-identified Burundian refugees who originally fled Burundi in 1972 and who have no possibility either to settle permanently in Tanzania or return to Burundi

- Bhutanese refugees in Nepal registered by UNHCR in the recent census and identified as in need of resettlement

- Iranian members of certain religious minorities

- Sudanese Darfurians living in a refugee camp in Anbar Governorate in Iraq would be eligible for processing if a suitable location can be identified

Priority Three is reserved for cases of family reunification, in which a refugee abroad is brought to the United States to be reunited with a close family member who also has refugee status. A list of nationalities eligible for Priority Three consideration is developed annually. The proposed countries for FY2008 were Afghanistan, Burma, Burundi, Colombia, Congo (Brazzaville), Cuba, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan and Uzbekistan.[10]

Individual application

The minority of applications that are made by individuals who have already entered the U.S. are judged on whether they meet the U.S. definition of "refugee" and on various other statutory criteria (including a number of bars that would prevent an otherwise-eligible refugee from receiving protection). There are two ways to apply for asylum while in the United States:

- If an asylum seeker has been placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge with the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which is a part of the Department of Justice, the individual may apply for asylum with the Immigration Judge.

- If an asylum seeker is inside the United States and has not been placed in removal proceedings, he or she may file an application with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, regardless of his or her legal status in the United States. However, if the asylum seeker is not in valid immigration status and USCIS does not grant the asylum application, USCIS may place the applicant in removal proceedings, in that case a judge will consider the application anew. The immigration judge may also consider the applicant for relief that the asylum office has no jurisdiction to grant, such as withholding of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture. Since the effective date of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act passed in 1996, an applicant must apply for asylum within one year[11] of entry or be barred from doing so unless the applicant can establish changed circumstances that are material to his or her eligibility for asylum or exceptional circumstances related to the delay.

There is no right to asylum in the United States; however, if an applicant is eligible, they have a procedural right to have the Attorney General make a discretionary determination as to whether the applicant should be admitted into the United States as an asylee. An applicant is also entitled to mandatory "withholding of removal" (or restriction on removal) if the applicant can prove that her life or freedom would be threatened upon return to her country of origin. The dispute in asylum cases litigated before the Executive Office for Immigration Review and, subsequently, the federal courts centers on whether the immigration courts properly rejected the applicant's claim that she is eligible for asylum or other relief.

The applicant has the burden of proving that he (or she) is eligible for asylum. To satisfy this burden, an applicant must show that she has a well-founded fear of persecution in her home country on account of either race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. The applicant can demonstrate her well-founded fear by demonstrating that she has a subjective fear (or apprehension) of future persecution in her home country that is objectively reasonable. An applicant's claim for asylum is stronger where she can show past persecution, in which case she will receive a presumption that she has a well-founded fear of persecution in her home country. The government can rebut this presumption by demonstrating either that the applicant can relocate to another area within her home country in order to avoid persecution, or that conditions in the applicant's home country have changed such that the applicant's fear of persecution there is no longer objectively reasonable. Technically, an asylum applicant who has suffered past persecution meets the statutory criteria to receive a grant of asylum even if the applicant does not fear future persecution. In practice, adjudicators will typically deny asylum status in the exercise of discretion in such cases, except where the past persecution was so severe as to warrant a humanitarian grant of asylum, or where the applicant would face other serious harm if returned to his or her country of origin. In addition, applicants who, according to the US Government, participated in the persecution of others are not eligible for asylum.[12]

A person may face persecution in his or her home country because of race, nationality, religion, ethnicity, or social group, and yet not be eligible for asylum because of certain bars defined by law. The most frequent bar is the one-year filing deadline. If an application is not submitted within one year following the applicant’s arrival in the United States, the applicant is barred from obtaining asylum unless certain exceptions apply. However, the applicant can be eligible for other forms of relief such as Withholding of Removal, which is a less favorable type of relief than asylum because it does not lead to a Green Card or citizenship. The deadline for submitting the application is not the only restriction that bars one from obtaining asylum. If an applicant persecuted others, committed a serious crime, or represents a risk to U.S. security, he or she will be barred from receiving asylum as well.[13]

In 1986 an Immigration Judge agreed not to send Fidel Armando-Alfanso back to Cuba, based on his membership in a particular social group (gay people) who were persecuted and feared further persecution by the government of Cuba.[14] The Board of Immigration Appeals upheld the decision in 1990, and in 1994, then-Attorney General Janet Reno ordered this decision to be a legal precedent binding on Immigration Judges and the Asylum Office, and established sexual orientation as a grounds for asylum.[14][15] However, in 2002 the Board of Immigration Appeals “suggested in an ambiguous and internally inconsistent decision that the ‘protected characteristic’ and ‘social visibility’ tests may represent dual requirements in all social group cases.”[16][17] The requirement for social visibility means that the government of a country from which the person seeking asylum is fleeing must recognize their social group, and that LGBT people who hide their sexual orientation, for example out of fear of persecution, may not be eligible for asylum under this mandate.[17]

In 1996 Fauziya Kasinga, a 19-year-old woman from the Tchamba-Kunsuntu people of Togo, became the first person to be granted asylum in the United States to escape female genital mutilation. In 2014 the Board of Immigration Appeals, the United States's highest immigration court, found for the first time that women who are victims of severe domestic violence in their home countries can be eligible for asylum in the United States.[18] However, this ruling was in the case of a woman from Guatemala and thus applies only to women from Guatemala.[18]

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca precedent

The term "well-founded fear" has no precise definition in asylum law. In INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1987), the Supreme Court avoided attaching a consistent definition to the term, preferring instead to allow the meaning to evolve through case-by-case determinations. However, in Cardoza-Fonseca, the Court did establish that a "well-founded" fear is something less than a "clear probability" that the applicant will suffer persecution. Three years earlier, in INS v. Stevic, 467 U.S. 407 (1984), the Court held that the clear probability standard applies in proceedings seeking withholding of deportation (now officially referred to as 'withholding of removal' or 'restriction on removal'), because in such cases the Attorney General must allow the applicant to remain in the United States. With respect to asylum, because Congress employed different language in the asylum statute and incorporated the refugee definition from the international Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, the Court in Cardoza-Fonseca reasoned that the standard for showing a well-founded fear of persecution must necessarily be lower.

An applicant initially presents his claim to an asylum officer, who may either grant asylum or refer the application to an Immigration Judge. If the asylum officer refers the application and the applicant is not legally authorized to remain in the United States, the applicant is placed in removal proceedings. After a hearing, an immigration judge determines whether the applicant is eligible for asylum. The immigration judge's decision is subject to review on two, and possibly three, levels. First, the immigration judge's decision can be appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals. In 2002, in order to eliminate the backlog of appeals from immigration judges, the Attorney General streamlined review procedures at the Board of Immigration Appeals. One member of the Board can affirm a decision of an immigration judge without oral argument; traditional review by three-judge panels is restricted to limited categories for which "searching appellate review" is appropriate. If the BIA affirms the decision of the immigration court, then the next level of review is a petition for review in the United States court of appeals for the circuit in which the immigration judge sits. The court of appeals reviews the case to determine if "substantial evidence" supports the immigration judge's (or the BIA's) decision. As the Supreme Court held in INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12 (2002), if the federal appeals court determines that substantial evidence does not support the immigration judge's decision, it must remand the case to the BIA for further proceedings instead of deciding the unresolved legal issue in the first instance. Finally, an applicant aggrieved by a decision of the federal appeals court can petition the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case by a discretionary writ of certiorari. But the Supreme Court has no duty to review an immigration case, and so many applicants for asylum forego this final step.

Notwithstanding his statutory eligibility, an applicant for asylum will be deemed ineligible if:

- the applicant participated in persecuting any other person on account of that other person's race, religion, national origin, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the community because he has been convicted in the United States of a particularly serious crime;

- the applicant has committed a serious non-political crime outside the United States prior to arrival;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the security of the United States;

- the applicant is inadmissible on terrorism-related grounds;

- the applicant has been firmly resettled in another country prior to arriving in the United States; or

- the applicant has been convicted of an aggravated felony as defined more broadly in the immigration context.

Conversely, even if an applicant is eligible for asylum, the Attorney General may decline to extend that protection to the applicant. (The Attorney General does not have this discretion if the applicant has also been granted withholding of deportation.) Frequently the Attorney General will decline to extend an applicant the protection of asylum if he has abused or circumvented the legal procedures for entering the United States and making an asylum claim.

Work permit and permanent residence status

An in-country applicant for asylum is eligible for a work permit (employment authorization) only if his or her application for asylum has been pending for more than 150 days without decision by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) or the Executive Office for Immigration Review. If an asylum seeker is recognized as a refugee, he or she may apply for lawful permanent residence status (a green card) one year after being granted asylum. Asylum seekers generally do not receive economic support. This, combined with a period where the asylum seeker is ineligible for a work permit is unique among developed countries and has been condemned from some organisations, including Human Rights Watch.[19]

Up until 2004, recipients of asylee status faced a wait of approximately fourteen years to receive permanent resident status after receiving their initial status, because of an annual cap of 10,000 green cards for this class of individuals. However, in May 2005, under the terms of a proposed settlement of a class-action lawsuit, Ngwanyia v. Gonzales, brought on behalf of asylees against CIS, the government agreed to make available an additional 31,000 green cards for asylees during the period ending on September 30, 2007. This is in addition to the 10,000 green cards allocated for each year until then and was meant to speed up the green card waiting time considerably for asylees. However, the issue was rendered somewhat moot by the enactment of the REAL ID Act of 2005 (Division B of United States Public Law 109-13 (H.R. 1268)), which eliminated the cap on annual asylee green cards. Currently, an asylee who has continuously resided in the US for more than one year in that status has an immediately available visa number.

Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program

An Unaccompanied Refugee Minor (URM) is any person who has not attained 18 years of age who entered the United States unaccompanied by and not destined to: (a) a parent, (b) a close non-parental adult relative who is willing and able to care for said minor, or (c) an adult with a clear and court-verifiable claim to custody of the minor; and who has no parent(s) in the United States.[20] These minors are eligible for entry into the URM program. Trafficking victims who have been certified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the United States Department of Homeland Security, and/or the United States Department of State are also eligible for benefits and services under this program to the same extent as refugees.

The URM program is coordinated by the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), a branch of the United States Administration for Children and Families. The mission of the URM program is to help people in need “develop appropriate skills to enter adulthood and to achieve social self-sufficiency.” To do this, URM provides refugee minors with the same social services available to U.S.-born children, including, but not limited to, housing, food, clothing, medical care, educational support, counseling, and support for social integration.[21]

History of the URM Program

URM was established in 1980 as a result of the legislative branch’s enactment of the Refugee Act that same year.[22] Initially, it was developed to “address the needs of thousands of children in Southeast Asia” who were displaced due to civil unrest and economic problems resulting from the aftermath of the Vietnam War, which had ended only five years earlier.[21] Coordinating with the United Nations and “utilizing an executive order to raise immigration quotas, President Carter doubled the number of Southeast Asian refugees allowed into the United States each month.”[23] The URM was established, in part, to deal with the influx of refugee children.

URM was established in 1980, but the emergence of refugee minors as an issue in the United States “dates back to at least WWII.”[22] Since that time, oppressive regimes and U.S. military involvement have consistently “contributed to both the creation of a notable supply of unaccompanied refugee children eligible to relocate to the United States, as well as a growth in public pressure on the federal government to provide assistance to these children."[22]

Since 1980, the demographic makeup of children within URM has shifted from being largely Southeast Asian to being much more diverse. Between 1999 and 2005, children from 36 different countries were inducted into the program.[22] Over half of the children who entered the program within this same time period came from Sudan, and less than 10% came from Southeast Asia.[22]

Perhaps the most commonly known group to enter the United States through the URM program was known as the “Lost Boys” of Sudan. Their story was made into a documentary by Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk. The film, Lost Boys of Sudan, follows two Sudanese refugees on their journey from Africa to America. It won an Independent Spirit Award and earned two national Emmy nominations.[24]

Functionality

In terms of functionality, the URM program is considered a state-administered program. The U.S. federal government provides funds to certain states that administer the URM program, typically through a state refugee coordinator’s office. The state refugee coordinator provides financial and programmatic oversight to the URM programs in his or her state. The state refugee coordinator ensures that unaccompanied minors in URM programs receive the same benefits and services as other children in out-of-home care in the state. The state refugee coordinator also oversees the needs of unaccompanied minors with many other stakeholders.[25]

ORR contracts with two faith-based agencies to manage the URM program in the United States; Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS)[26] and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). These agencies identify eligible children in need of URM services; determine appropriate placements for children among their national networks of affiliated agencies; and conduct training, research and technical assistance on URM services. They also provide the social services such as: indirect financial support for housing, food, clothing, medical care and other necessities; intensive case management by social workers; independent living skills training; educational supports; English language training; career/college counseling and training; mental health services; assistance adjusting immigration status; cultural activities; recreational opportunities; support for social integration; and cultural and religious preservation.[27]

The URM services provided through these contracts are not available in all areas of the United States. The 14 states that participate in the URM program include: Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington and the nation’s capital, Washington D.C.[27]

Adoption of URM Children

Although they are in the United States without the protection of their family, URM-designated children are not generally eligible for adoption. This is due in part to the Hague Convention on the Protection and Co-Operation in Respect of Inter-Country Adoption, otherwise known as the Hague Convention. Created in 1993, the Hague Convention established international standards for inter-country adoption.[28] In order to protect against the abduction, sale or trafficking of children, these standards protect the rights of the biological parents of all children. Children in the URM program have become separated from their biological parents and the ability to find and gain parental release of URM children is often extremely difficult. Most children, therefore, are not adopted. They are served primarily through the foster care system of the participating states. Most will be in the custody of the state (typically living with a foster family) until they become adults. Reunification with the child’s family is encouraged whenever possible.

U.S. government support after arrival

As soon as people seeking asylum in the United States are accepted as refugees they are given public assistance like any other citizen in need such as cash welfare, food assistance, and health coverage.[29]

The year 2015 has seen the greatest displacement of people around the world since World War II with 65.3 million people having to flee their homes.[30] In monetary amounts, the U.S. Government's international humanitarian program of the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) requested in the fiscal year 2016 that 442.7 million dollars be allocated to Refugee Admission programs that relocate refugees in communities across the country.[31] Despite this support there are scarce resources for refugees as the inflow increases. President Obama made a "Call to Action" for the private sector to make a commitment to help refugees and their opportunity for jobs as well as accessibility to their needs.[32]

LGBT asylum seekers

The United States offers political asylum to some LGBT individuals who face potential criminal penalties.[33][34] The first person to receive asylum in the US on the basis of sexual orientation was a Cuban national, whose case was presented in 1989.[35] A 2015 report issued by the LGBT Freedom and Asylum network identifies best practices for supporting LGBT asylum seekers in the US[36] and the US State Department has also issued a factsheet on protecting LGBT refugees.[37]

Film

The 2000 documentary film Well-Founded Fear, from filmmakers Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini marked the first time that a film crew was privy to the private proceedings at the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), where individual asylum officers ponder the often life-or-death fate of the majority of immigrants seeking asylum. The film analyzes the US asylum application process by following several asylum applicants and asylum officers. It provided the first high-profile, behind-the-scenes look at the process for seeking asylum in the United States.The film was featured at the Sundance Film Festival in documentary competition. Well-Founded Fear was broadcast in June, 2000 on PBS as part of POV and internationally on CNN on May 27, 2000 under the title Asylum in America.[38]

See also

- Negusie v. Holder (2009)

- Political Asylum

- Immigration and Naturalization Service

- Well-Founded Fear

- Georgetown University Law Center, Center for Applied Legal Studies

Sources

- David Weissbrodt and Laura Danielson, Immigration Law and Procedure, 5th ed., West Group Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-314-15416-7

Notes and references

- ↑ Spreadsheet: Inflows of asylum seekers into selected OECD countries. Associated migration report: OECD International Migration Outlook 2009.

- ↑ UNHCR (2015). Asylum Trends 2014: Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries, p. 20. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Scott Rempell, Defining Persecution, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1941006

- 1 2 US Department of State "Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2014"

- 1 2 US Department of State "Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2015"

- 1 2 US Department of State "Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2016"

- 1 2 US Department of State "Proposed refugee admissions for fiscal year 2017"

- ↑ US Department of State "Arrivals by Region 2016_09_30"

- ↑ "Presidential Determination - Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2017"

- 1 2 Report to the Congress Submitted on Behalf of The President of The United States to the Committees on the Judiciary United States Senate and United States House of Representatives in Fulfillment of the Requirements of Section 207(E) (1)-(7) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, Released by the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration of the United States Department of State, p. 8

- ↑ Schaefer, Kimberley. "Applying for Asylum in the United States". http://www.kschaeferlaw.com/. Kimberley Schaefer. Retrieved 6 August 2012. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Schaefer, Kimberley. "Asylum in the United States". http://www.kschaeferlaw.com/immigration-overview/asylum. Kimberley Schaefer. Retrieved 6 August 2012. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Kutidze, Givi. "Green Card Through Asylum". http://www.us-counsel.com/green-cards/green-card-asylum. Givi Kutidze. Retrieved 20 November 2016. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 "Asylum Based on Sexual Orientation and Fear of Persecution". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ "How Will Ugandan Gay Refugees Be Received By U.S.?". NPR.org. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Marouf, Fatma E. (2008) "The Emerging Importance of "Social Visibility" in Defining a Particular Social Group and Its Potential Impact on Asylum Claims Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender". Scholarly Works. Paper 419, pg. 48

- 1 2 "Social visibility, asylum law, and LGBT asylum seekers". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- 1 2 http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/us/victim-of-domestic-violence-in-guatemala-is-ruled-eligible-for-asylum-in-us.html?_r=0

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (12 November 2013). US: Catch-22 for Asylum Seekers. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Congressional Research Service Report to Congress, Unaccompanied Refugee Minors, Policyarchive.org pg. 7

- 1 2 "About Unaccompanied Refugee Minors.". Department of Health and Human Services.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Unaccompanied Refugee Minors" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- ↑ "The Vietnam War and Its Impact - Refugees and 'boat people'". Encyclopedia of the New American Nation.

- ↑ "Lost Boys of Sudan :: About The Film". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ "The United States Unaccompanied Refugee Minor Program" (PDF). United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- ↑ "LIRS – Stand for Welcome with Migrants and Refugees". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- 1 2 "Unaccompanied Refugee Minors". Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Department of State, Office of Children’s Issues: Intercountry Adoption Overview Adoption.state.gov

- ↑ "Ten Facts About U.S. Refugee Resettlement". migrationpolicy.org. 2015-10-20. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ "Global Refugee Crisis". Partnership for Refugees. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Congressional Presentation Document Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) FY 2016 [PDF] - U.S. Department of State Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration

- ↑ "Private Sector Call to Action on Refugees". www.state.gov. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Kerr, Jacob (June 19, 2015). "LGBT Asylum Seekers Not Getting Enough Relief In U.S., Report Finds". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Taracena, Maria Inés (May 27, 2014). "LGBT Global Persecution Leads to Asylum Seekers in Southern AZ". Arizona Public Media, NPR.

- ↑ "Social visibility, asylum law, and LGBT asylum seekers". Twin Cities Daily Planet. October 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Best Practice Guide: Supporting LGBT Asylum Seekers in the United States" (PDF). LGBT Freedom and Asylum Network.

- ↑ US Department of State LGBT Human Rights Fact Sheet, US Department of State, accessed May 14, 2016

- ↑ http://www.cnn.com/CNN/Programs/presents/index.asylum.html

External links

- Asylum in the United States

- Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration of the U.S. Department of State

- Well-Founded Fear Official site

- Well-Founded Fear at POV

- Eligibility for Refugee Assistance and Services through the Office of Refugee Resettlement, United States Department of Health and Human Services

- Refugee Act of 1980, text hosted by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, United States Department of Health and Human Services

- Michael J. McBride, The evolution of US immigration and refugee policy: public opinion, domestic politics and UNHCR, New Issues in Refugee Research, May 1999

- Audrey Singer and Jill Wilson, From 'There' to 'Here': Refugee Resettlement in Metropolitan America, Brookings Institution, September 2006

- PARDS.ORG Political Asylum Research and Documentation Service