Orgelbüchlein

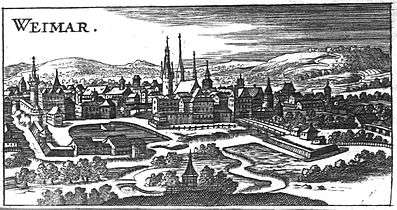

The Orgelbüchlein ("Little Organ Book") BWV 599−644 is a collection of 46 chorale preludes for organ written by Johann Sebastian Bach. All but three of them were composed during the period 1708–1717, while Bach was court organist at the ducal court in Weimar. The remaining three, along with a short two-bar fragment, were added in 1726 or later, after Bach's appointment as cantor at the Thomasschule in Leipzig.

The collection was originally planned as a set of 164 chorale preludes spanning the whole liturgical year. The chorale preludes form the first of Bach's masterpieces for organ with a mature compositional style in marked contrast to his previous compositions for the instrument. Although each of them takes a known Lutheran chorale and adds a motivic accompaniment, Bach explored a wide diversity of forms in the Orgelbüchlein. Many of the chorale preludes are short and in four parts, requiring only a single keyboard and pedal, with an unadorned cantus firmus. Others involve two keyboards and pedal: these include several canons, four ornamental four-part preludes, with elaborately decorated chorale lines, and a single chorale prelude in trio sonata form. The Orgelbüchlein has a four-fold purpose: it is a collection of organ music for church services, a treatise on composition, a religious statement, and an organ-playing manual.

| “ | A further step towards perfecting this form was taken by Bach when he made the contrapuntal elements in his music a means of reflecting certain emotional aspects of the words. Pachelbel had not attempted this; he lacked the fervid feeling which would have enabled him thus to enter into his subject. And it is entering into it, and not a mere depicting of it. For, once more be it said, in every vital movement of the world external to us we behold the image of a movement within us; and every such image must react upon us to produce the corresponding emotion in that inner world of feeling. | ” | |

| — Philipp Spitta, 1873, writing about the Orgelbüchlein in Volume I of his biography of Bach | |||

| “ | Here Bach has realised the ideal of the chorale prelude. The method is the most simple imaginable and at the same time the most perfect. Nowhere is the Dürer-like character of his musical style so evident as in these small chorale preludes. Simply by the precision and the characteristic quality of each line of the contrapuntal motive he expresses all that has to be said, and so makes clear the relation of the music to the text whose title it bears. | ” | |

| — Albert Schweitzer, Jean-Sebastien Bach, le musicien-poête, 1905 | |||

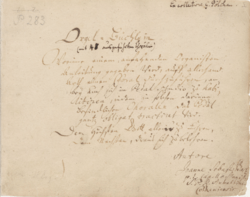

Title page

Orgel-Büchlein

Worrine einem anfahenden Organisten

Anleitung gegeben wird, auff allerhand

Arth einen Choral durchzuführen, an-

bey auch sich im Pedal studio zu habi-

litiren, indem in solchen darinne

befindlichen Choralen das Pedal

gantz obligat tractiret wird.

Dem Höchsten Gott allein' zu Ehren,

Dem

Nechsten, draus sich zu belehren.

Autore

Joanne Sebast. Bach

p. t. Capellae Magistri

S. P. R. Anhaltini-

Cotheniensis.

Title page of autograph of the Orgelbüchlein

The title page of the autograph score reads in English translation:[1]

Little Organ Book

In which a beginning organist receives given instruction as to performing a chorale in a multitude of ways while achieving mastery in the study of the pedal, since in the chorales contained herein the pedal is treated entirely obbligato.

In honour of our Lord alone

That my fellow man his skill may hone.

Composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, Capellmeister to his Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen

| Planned content of the Orgelbüchlein as indicated in the autograph manuscript[2] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Title | Liturgical significance | Page | BWV |

| 1 | Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland | Advent | 1 | 599 |

| 2 | Gott, durch dein Güte or Gottes Sohn ist kommen | Advent | 2-3 | 600 |

| 3 | Herr Christ, der ein'ge Gottessohn or Herr Gott, nun sei gepreiset | Advent | 4 | 601 |

| 4 | Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott | Advent | 5 | 602 |

| 5 | Puer natus in Bethlehem | Christmas | 6-7 | 603 |

| 6 | Lob sei Gott in des Himmels Thron | Christmas | 7 | |

| 7 | Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ | Christmas | 8 | 604 |

| 8 | Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich | Christmas | 9 | 605 |

| 9 | Von Himmel hoch, da komm ich her | Christmas | 10 | 606 |

| 10 | Von Himmel kam der Engel Schar | Christmas | 11-10 | 607 |

| 11 | In dulci jubilo | Christmas | 12-13 | 608 |

| 12 | Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich | Christmas | 14 | 609 |

| 13 | Jesu, meine Freude | Christmas | 15 | 610 |

| 14 | Christum wir sollen loben schon | Christmas | 16 | 611 |

| 15 | Wir Christenleut | Christmas | 17 | 612 |

| 16 | Helft mir Gotts Güte preisen | New Year | 18 | 613 |

| 17 | Das alte Jahr vergangen ist | New Year | 19 | 614 |

| 18 | In dir ist Freude | New Year | 20-21 | 615 |

| 19 | Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin [Nunc dimittis] | Purification | 22 | 616 |

| 20 | Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf | Purification | 23-23a | 617 |

| 21 | O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig | Passiontide | 24-24a | 618 |

| 22 | Christe, du Lamm Gottes | Passiontide | 25 | 619 |

| 23 | Christus, der uns selig macht | Passiontide | 26 | 620a/620 |

| 24 | Da Jesu an dem Kreuze stund | Passiontide | 27 | 621 |

| 25 | O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross | Passiontide | 28-29 | 622 |

| 26 | Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, dass du für uns gestorben bist | Passiontide | 30 | 623 |

| 27 | Hilf Gott, das mir's gelinge | Passiontide | 31-30a | 624 |

| 28 | O Jesu, wie ist dein Gestalt | Passiontide | 32 | |

| 29 | O Traurigkeit, o Herzeleid (fragment) | Passiontide | 33 | Anh. 200 |

| 30 | Allein nach dir, Herr, allein nach dir, Herr Jesu Christ, verlanget mich | Passiontide | 34-35 | |

| 31 | O wir armen Sünder | Passiontide | 36 | |

| 32 | Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen | Passiontide | 37 | |

| 33 | Nun gibt mein Jesus gute Nacht | Passiontide | 38 | |

| 34 | Christ lag in Todesbanden | Easter | 39 | 625 |

| 35 | Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der den Tod überwand | Easter | 40 | 626 |

| 36 | Christ ist erstanden | Easter | 41-43 | 627 |

| 37 | Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ | Easter | 44 | 628 |

| 38 | Erscheinen ist der herrliche Tag | Easter | 45 | 629 |

| 39 | Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn | Easter | 46-47 | 630 |

| 40 | Gen Himmel aufgefahren ist | Ascension | 48 | |

| 41 | Nun freut euch, Gottes Kinder, all | Ascension | 49 | |

| 42 | Komm, Heiliger Geist, erfüll die Herzen deiner Gläubigen | Pentecost | 50-51 | |

| 43 | Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott | Pentecost | 52-53 | |

| 44 | Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist | Pentecost | 54 | 631a/631 |

| 45 | Nun bitten wir den Heil'gen Geist | Pentecost | 55 | |

| 46 | Spiritus Sancti gratia or Des Heil'gen Geistes reiche Gnad | Pentecost | 56 | |

| 47 | O Heil'ger Geist, du göttlich's Feuer | Pentecost | 57 | |

| 48 | O Heiliger Geist, o heiliger Gott | Pentecost | 58 | |

| 49 | Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend | Pentecost | 59 | 632 |

| 50 | Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier | Pentecost | 60 | 634 |

| 51 | Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (distinctius) | Pentecost | 61 | 633 |

| 52 | Gott der Vater wohn uns bei | Trinity | 62-63 | |

| 53 | Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr | Trinity | 64 | |

| 54 | Der du bist drei in Einigkeit | Trinity | 65 | |

| 55 | Gelobet sei der Herr, der Gott Israel [Benedictus] | St. John the Baptist | 66 | |

| 56 | Meine Seele erhebt den Herren [Magnificat] | Visitation | 67 | |

| 57 | Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir | St. Michael and All Angels | 68 | |

| 58 | Er stehn vor Gottes Throne | St. Michael and All Angels | 69 | |

| 59 | Herr Gott, dich loben wir | St. Simon and St. Jude, Apostles | 70-71 | |

| 60 | O Herre Gott, dein göttlich Wort | Reformation Festival | 72 | |

| 61 | Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot | Ten Commandments | 73 | 635 |

| 62 | Mensch, willst du leben seliglich | Ten Commandments | 74 | |

| 63 | Herr Gott, erhalt uns für und für | Ten Commandments | 75 | |

| 64 | Wir glauben all an einem Gott | Creed | 76-77 | |

| 65 | Vater unser im Himmelreich | Lord's Prayer | 78 | 636 |

| 66 | Christ, unser Herr, zu Jordan kam | Holy Baptism | 79 | |

| 67 | Auf tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir [Psalm 130] | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 80 | |

| 68 | Erbarm dich mein, o Herre Gott | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 81 | |

| 69 | Jesu, der du meine Seele | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 82 | |

| 70 | Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 83 | |

| 71 | Ach Gott und Herr | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 84 | |

| 72 | Herr Jesu Christ, du höchstes Gut | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 85 | |

| 73 | Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 86 | |

| 74 | Wo soll ich fliehen hin | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 87 | |

| 75 | Wir haben schwerlich | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 88 | |

| 76 | Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 89 | 637 |

| 77 | Es ist das Heil uns kommen her | Confession, Penitence and Justification | 90 | 638 |

| 78 | Jesus Christus, unser Heiland | Lord's Supper | 91 | |

| 79 | Gott sei gelobet und gebenedeiet | Lord's Supper | 92-93 | |

| 80 | Der Herr is mein getreuer Hirt [Psalm 23] | Lord's Supper | 94 | |

| 81 | Jetzt komm ich als ein armer Gast | Lord's Supper | 95 | |

| 82 | O Jesu, du edle Gabe | Lord's Supper | 96 | |

| 83 | Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, dass du das Lämmlein worden bist | Lord's Supper | 97 | |

| 84 | Ich weiss ein Blümlein hübsch und fein | Lord's Supper | 98 | |

| 85 | Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g'mein | Lord's Supper | 99 | |

| 86 | Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren [Psalm 103] | Lord's Supper | 100-101 | |

| 87 | Wohl dem, der in Gottes Furcht steht | Christian Life and Conduct | 102 | |

| 88 | Wo Gott zum Haus nicht gibt sein Gunst [Psalm 127] | Christian Life and Conduct | 103 | |

| 89 | Was mein Gott will, das g'scheh allzeit | Christian Life and Conduct | 104 | |

| 90 | Kommt her zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn | Christian Life and Conduct | 105 | |

| 91 | Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ | Christian Life and Conduct | 106-107 | 639 |

| 92 | Weltlich Ehr und zeitlich Gut | Christian Life and Conduct | 107 | |

| 93 | Von Gott will ich nicht lassen | Christian Life and Conduct | 108 | |

| 94 | Wer Gott vertraut | Christian Life and Conduct | 109 | |

| 95 | Wie's Gott gefällt, so gefällt mir's auch | Christian Life and Conduct | 110 | |

| 96 | O Gott, du frommer Gott | Christian Life and Conduct | 111 | |

| 97 | In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr [Psalm 31] | Christian Life and Conduct | 112 | |

| 98 | In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr (alia modo) | Christian Life and Conduct | 113 | 640 |

| 99 | Mag ich Unglück nicht widertstahn | Christian Life and Conduct | 114 | |

| 100 | Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein | Christian Life and Conduct | 115 | 641 |

| 101 | An Wasserflüssen Babylon [Psalm 137] | Christian Life and Conduct | 116-117 | |

| 102 | Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz | Christian Life and Conduct | 118 | |

| 103 | Frisch auf, mein Seel, verzage nicht | Christian Life and Conduct | 119 | |

| 104 | Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid | Christian Life and Conduct | 120 | |

| 105 | Ach Gott, erhör mein Seufzen und Wehklagen | Christian Life and Conduct | 121 | |

| 106 | So wünsch ich nun eine gute Nacht [Psalm 42] | Christian Life and Conduct | 122 | |

| 107 | Ach lieben Christen, seid getrost | Christian Life and Conduct | 123 | |

| 108 | Wenn dich Unglück tut greifen an | Christian Life and Conduct | 124 | |

| 109 | Keinen hat Gott verlassen | Christian Life and Conduct | 125 | |

| 110 | Gott ist mein Heil, mein Hülf und Trost | Christian Life and Conduct | 126 | |

| 111 | Wass Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan, kein einig Mensch ihn tadeln kann | Christian Life and Conduct | 127 | |

| 112 | Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan, es bleibt gerecht sein Wille | Christian Life and Conduct | 128 | |

| 113 | Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten | Christian Life and Conduct | 129 | 642 |

| 114 | Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein [Psalm 12] | Psalm Hymns | 130 | |

| 115 | Es spricht der Unweisen Mund wohl [Psalm 14] | Psalm Hymns | 131 | |

| 116 | Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott [Psalm 46] | Psalm Hymns | 132 | |

| 117 | Es woll uns Gott genädig sein [Psalm 67] | Psalm Hymns | 133 | |

| 118 | Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit [Psalm 124] | Psalm Hymns | 134 | |

| 119 | Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält [Psalm 124] | Psalm Hymns | 135 | |

| 120 | Wie schön leuchtet der Morgernstern | Word of God and Christian Church | 136-137 | |

| 121 | Wie nach einer Wasserquelle [Psalm 42] | Word of God and Christian Church | 138 | |

| 122 | Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort | Word of God and Christian Church | 139 | |

| 123 | Lass mich dein sein und bleiben | Word of God and Christian Church | 140 | |

| 124 | Gib Fried, o frommer, treuer Gott | Word of God and Christian Church | 141 | |

| 125 | Du Friedefürst, Herr Jesu Christ | Word of God and Christian Church | 142 | |

| 126 | O grosser Gott von Macht | Word of God and Christian Church | 143 | |

| 127 | Wenn mein Stündlein vorhanden ist | Death and Dying | 144 | |

| 128 | Herr Jesu Christ, wahr Mensch und Gott | Death and Dying | 145 | |

| 129 | Mitten wir im Leben sind | Death and Dying | 146-147 | |

| 130 | Alle Menschen müssen sterben | Death and Dying | 148 | |

| 131 | Alle Menschen müssen sterben (alio modo) | Death and Dying | 149 | 643 |

| 132 | Valet will ich dir geben | Death and Dying | 150 | |

| 133 | Nun lasst uns den Leib begraben | Death and Dying | 151 | |

| 134 | Christus, der ist mein Leben | Death and Dying | 152 | |

| 135 | Herzlich lieb hab ich dich, o Herr | Death and Dying | 152-153 | |

| 136 | Auf meinen lieben Gott | Death and Dying | 154 | |

| 137 | Herr Jesu Christ, ich weiss gar wohl | Death and Dying | 155 | |

| 138 | Mach's mit mir, Gott, nach deiner Güt | Death and Dying | 156 | |

| 139 | Herr Jesu Christ, meins Lebens Licht | Death and Dying | 157 | |

| 140 | Mein Wallfahrt ich vollendet hab | Death and Dying | 158 | |

| 141 | Gott hat das Evangelium | Death and Dying | 159 | |

| 142 | Ach Gott, tu dich erbarmen | Death and Dying | 160 | |

| 143 | Gott des Himmels und der Erden | Morning | 161 | |

| 144 | Ich dank dir, lieber Herre | Morning | 162 | |

| 145 | Aus Meines Herzens Grunde | Morning | 163 | |

| 146 | Ich dank dir schon | Morning | 164 | |

| 147 | Das walt mein Gott | Morning | 165 | |

| 148 | Christ, der du bist der helle Tag | Evening | 166 | |

| 149 | Christe, der du bist Tag und Licht | Evening | 167 | |

| 150 | Werde munter, mein Gemüte | Evening | 168 | |

| 151 | Nun ruhen alle Wälder | Evening | 169 | |

| 152 | Dankt dem Herrn, denn er ist sehr freundlich [Psalm 136] | After Meals | 170 | |

| 153 | Nun lasst uns Gott dem Herren | After Meals | 171 | |

| 154 | Lobet dem Herren, denn er ist sehr freundlich [Psalm 147] | After Meals | 172 | |

| 155 | Singen wir aus Herzensgrund | After Meals | 173 | |

| 156 | Gott Vater, der du deine Sonn | Good Weather | 174 | |

| 157 | Jesue, meines Herzens Freud | Appendix | 175 | |

| 158 | Ach, was soll ich Sűnder machen | Appendix | 176 | |

| 159 | Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig | Appendix | 177 | 644 |

| 160 | Ach, was ist doch unser Leben | Appendix | 178 | |

| 161 | Allenthalben, wo ich gehe | Appendix | 179 | |

| 162 | Hast du denn, Jesu, dein Angesicht gänzlich verborgen or Soll ich denn, Jesu, mein Leben in Trauern beschliessen |

Appendix | 180 | |

| 163 | Sei gegrüsset, Jesu gütig or O Jesu, du edle Gabe | Appendixhe | 181 | |

| 164 | Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele | Appendix | 182 | |

History

Bach's formal training as a musician started when he was enrolled as a chorister at the Michaelskirche in Lüneburg in 1700–1702. Manuscripts in Bach's hand recently discovered in Weimar by the Bach scholars Peter Wollny and Michael Maul show that while in Lüneburg he studied the organ with Georg Böhm, composer and organist at the Johanniskirche. The documents are hand copies made in Böhm's home in tablature format of organ compositions by Reincken, Buxtehude and others. They indicate that already at the age of 15 Bach was an accomplished organist, playing some of the most demanding repertoire of the period.[4] After a brief spell in Weimar as court musician in the chapel of Johann Ernst, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, Bach was appointed as organist at St. Boniface's Church (now called the Bachkirche) in Arnstadt in the summer of 1703, having inspected and reported on the organ there earlier in the year. In 1705–1706 he was granted leave from Arnstadt to study with the organist and composer Dieterich Buxtehude in Lübeck, a pilgrimage he famously made on foot. In 1707 Bach became organist at St. Blasius' Church in Mühlhausen, before his second appointment at the court in Weimar in 1708 as concertmaster and organist, where he remained until 1717.

During the period before his return to Weimar, Bach had composed a set of 31 chorale preludes: these were discovered independently by Christoph Wolff and Wilhelm Krunbach in the library of Yale University in the mid-1980s and first published as Das Arnstadter Orgelbuch. They form part of a larger collection of organ music compiled in the 1790s by the organist Johann Gottfried Neumeister (1756–1840) and are now referred to as the Neumeister Chorales BWV 1090–1120. These chorale preludes are all short, either in variation form or fughettas.[5] Only a few other organ works based on chorales can be dated with any certainty to this period. These include the chorale partitas BWV 766-768 and 770, all sets of variations on a given chorale.[6]

During his time as organist at Arnstadt, Bach was upbraided in 1706 by the Arnstadt Consistory "for having hitherto introduced sundry curious embellishments in the chorales and mingled many strange notes in them, with the result that the congregation has been confused." The type of chorale prelude to which this refers, often called the "Arnstadt type", were used to accompany the congregation with modulating improvisatory sections between the verses: examples that are presumed to be of this form include BWV 715, 722, 726, 729, 732 and 738. The earliest surviving autograph manuscript of a chorale prelude is BWV 739, Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, based on an Advent hymn. It dates from 1705 and possibly was prepared for Bach's visit to Lübeck.[7]

-

Autograph manuscript of BWV 739

-

Cranach altarpiece in St Peter und Paul, where Bach played the organ

-

View of Weimar, 1686: Wilhelmsburg in centre, St Peter and Paul behind, Rote Schloss over footbridge on left

-

Wilhelmsburg, Weimar, c 1730, built in the 1650s and destroyed by fire in 1774

Purpose

| “ | The Orgelbüchlein is simultaneously a compositional treatise, a collection of liturgical organ music, an organ method, and a

theological statement. These four identities are so closely intertwined that it is hard to know where one leaves off and another begins. |

” | |

| — Stinson (1999, p. 25) | |||

Compositional style

Although there are a few important departures, the chorale preludes of the Orgelbüchlein were composed with a number of common stylistic features, which characterise and distinguish the so-called "Orgelbüchlein style:"[8]

- They are harmonisations of a cantus firmus which is taken by the soprano voice.

- They are in four parts, with three accompanying voices.

- The harmonies are filled out in the accompanying voices by motifs or figures derived from the cantus and written imitatively.

- They begin directly with the cantus, either with or without accompaniment.

- There are no breaks between the lines of the cantus for ritornellos or interludes in the accompanying voices.

- The notes ending verse lines in the cantus are marked by fermata (pauses).

Exceptions include:

- BWV 611, Christum wir sollen loben schon, where the cantus is in the alto voice

- BWV 600, 608, 618, 619, 620, 624, 629 and 633/634 where the soprano cantus is in canon with another voice.

- BWV 615, In dir ist Freude, where the cantus is heard in canon in all the voices over the accompanying motifs.

- BWV 599, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, and BWV 619, Christe du Lamm Gottes, which are written for five voices.

- BWV 639, Ich ruf' zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, which is written for three voices.

- BWV 617, 618, 619 and 637, where the accompaniment starts before the cantus.

Chorale Preludes BWV 599–644

- The brief descriptions of the chorale preludes are based on the detailed analysis in Williams (2003) and Stinson (1999).

- To listen to a MIDI recording, please click on the link.

- To listen to an MP3 recording of James Kibbie on the 1717 Trost organ, St. Walpurgis, Großengottern, Germany, please right click on the external link.

Advent BWV 599–602

- BWV 599 Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland [Come now Saviour of heathens]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Luther's advent hymn Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland with the translation in English of George MacDonald.

|

|

Although it has often been suggested that this opening advent chorale prelude resembles a French overture, in construction, with its texture of arpeggiated chords, it is more similar to the baroque keyboard preludes of German and French masters, such as Couperin. The accompanying motif in the lower three or sometimes four parts is derived from a suspirans in the melodic line, formed of a semiquaver (16th note) rest—a "breath"—followed by three semiquavers and a longer fourth note. Some commentators have seen this falling figure as representing a descent to earth, but it could equally well reflect a repetition of the words "Nun komm" in the text. The suspirans is made up of intervals of a rising second, a falling fourth following by yet another rising second. It is derived from the first line of the melody of the cantus firmus and often shared out freely between voices in the accompaniment. The mystery of the coming of the Saviour is reflected by the somewhat hidden cantus firmus, over harmonies constantly reinventing themselves. It is less predictable and regular than other settings of the same hymn by Bach or predecessors like Buxtehude, only the second and third lines having any regularity. The last line repeats the first but with the suspirans suppressed and the dotted rhythms of the bass replaced by a long pedal note, possibly reflecting the wonder described in the third and fourth lines of the first verse.

- BWV 600 Gott, durch deine Güte [God, through your goodness] (or Gottes Sohn ist kommen [The Son of God is come])

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first of three verses of Johann Spannenberg's advent hymn with the translation in English of Charles Sanford Terry.

|

|

It is set to the same melody as Johann Roh's advent hymn Gottes Sohn ist kommen, the first verse of which is given here with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

This chorale prelude is a canon at the octave in the soprano and tenor voices, with the tenor entering one bar after the soprano. The stops for the canonic parts were explicitly marked by Bach in the autograph score, with the high tenor part in the pedal, written at the pitch Bach intended and also within the compass of the Weimar organ. Bach left no indication that the manualiter parts were to be played on two keyboards: indeed, as Stinson (1996) points out, the autograph score brackets all the keyboard parts together; in addition technically at certain points the keyboard parts have to be shared between the two hands. The accompaniment is a skillful and harmonious moto perpetuo in the alto and bass keyboard parts with flowing quavers (eighth notes) in the alto, derived from the first four quaver suspirans figure, played above a walking bass in detached crotchets (quarter notes). The hymn was originally written in duple time but, to facilitate the canonic counterpoint, Bach adopted triple time with a minim beat, at half the speed of the bass. The bass accompaniment at first is derived directly from the melody; during the pauses in the soprano part, a second motif recurs. The continuous accompaniment in quavers and crotchets is an example of the first of two types of joy motif described by Schweitzer (1911b), used to convey "direct and naive joy." In the words of Albert Riemenschneider, "the exuberance of the passage work indicates a joyous background."

- BWV 601 Herr Christ, der einge Gottes-Sohn [Lord Christ, the only Son of God] (or Herr Gott, nun sei gepreiset [Lord God, now be praised])

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of Elisabeth Cruciger's hymn for Epiphany Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn with the English translation of Myles Coverdale.

|

|

The same melody was used in the postprandial grace Herr Gott, nun sei gepreiset, the first verse of which is given below with the English translation of Charles Sanford Terry.

|

|

According to the chronology of Stinson (1996), this chorale prelude was probably the first to be entered by Bach in the autograph manuscript. Already it shows with beguiling simplicity all the features typical of the Orgelbüchlein preludes. The cantus firmus is presented unadorned in the soprano line with the other three voices on the same keyboard and in the pedal. The accompaniment is derived from the suspirans pedal motif of three semiquavers (16th notes) followed by two quavers (eighth notes). For Schweitzer (1911b) this particular motif signified "beatific joy", representing either "intimate gladness or blissful adoration." Although the chorale prelude cannot be precisely matched to the words of either hymn, the mood expressed is in keeping both with joy for the coming of Christ and gratitude for the bountifulness of God. The motif, which is anticipated and echoed in the seamlessly interwoven inner parts, was already common in chorale preludes of the period. Easy to play with alternating feet, it figured in particular in the preludes of Buxtehude and Böhm as well as an earlier manualiter setting of the same hymn by Bach's cousin, Johann Gottfried Walther. Bach, however, goes beyond the previous models, creating a unique texture in the accompaniment which accelerates, particularly in the pedal, towards the cadences. Already in the opening bar, as Williams (2003) points out, the subtlety of Bach's compositional skills are apparent. The alto part anticipates the pedal motif and, with it and the later dotted figure, echos the melody in the soprano. This type of writing—in this case with hidden and understated imitation between the voices, almost in canon, conveying a mood of intimacy—was a new feature introduced by Bach in his Orgelbüchlein.

- BWV 602 Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott [Praise be to God Almighty]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first two verses of Michael Weisse's advent hymn with the English translation of John Gambold.

|

|

The cantus firmus for this chorale prelude originates in the Gregorian chant Conditor alme siderum. Although in the phrygian mode, Bach slightly modifies it, replacing some B♭s by B♮s in the melody, but still ends in the key of A. The accompaniment is composed of two motifs, both suspirans: one in the inner parts contains a joy motif; and the other, shared between all three lower parts, is formed of three semiquavers (16th notes) and a longer note or just four semiquavers. In the pedal part this prominent descending motif has been taken to symbolise the "coming down of divine Majesty." Some commentators have suggested that the motion of the inner parts in parallel thirds or sixths might represent the Father and Son in the hymn. Albert Riemenschneider described the lower voices as creating "an atmosphere of dignified praise."

Christmas BWV 603–612

- BWV 603 Puer natus in Bethlehem [A boy is born in Bethlehem]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of the traditional Latin carol Puer natus in Bethlehem with the English translation of Hamilton Montgomerie MacGill.

|

|

The cantus firmus in the soprano voice of this chorale prelude is a slight variant of the treble part of a four-part setting of Puer natus by Lossius. The chorale prelude is in four parts for single manual and pedals. It is unusual in that in most published versions no repeats are marked. However, in the autograph score there are markings by Bach at the end of the score which might indicate that a repeat of the whole prelude was envisaged with first and second time versions for the last bar. Some recent editions have incorporated this suggestion. The two inner voices and pedal follow the usual Orgelbüchlein pattern, providing a harmonious accompaniment, with gently rocking quavers in the inner voices and a repeated motif in the pedal, rising first and then descending in crotchet steps. Various commentators have proposed interpretations of the accompanying motifs: the rocking motif to suggest the action of swaddling; and the pedal motif as symbolising either the "journey of the Magi" to Bethlehem (Schweitzer (1905)) or Christ's "descent to earth" (Chailley (1974)). On a purely musical level, a mood of increasing wonder is created as the accompaniment intensifies throughout the chorale with more imitative entries in the inner parts.[9][10]

- BWV 604 Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ [Praised be you, Jesus Christ] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Martin Luther's version "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" (1524) of the traditional Christmas hymn Gratis nunc omnes reddamus, with the English translation of Myles Coverdale.

|

|

Bach used the same hymn in other organ compositions as well as in the cantatas BWV 64, 91 and 248, parts I and III (the Christmas Oratorio). The chorale prelude is scored for two manuals and pedal, with the cantus firmus in the soprano voice on the upper manual. On the lower manual the two inner voices provide the harmonic accompaniment, moving stepwise in alternating semiquavers. The pedal part responds throughout with a constantly varying motif involving octave semiquaver leaps. The chorale prelude is in the mixolydian mode. Combined with the unadorned but singing melody and its gentle accompaniment, this produces a mood of tenderness and rapture.

- BWV 605 Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich [The day is so full of joy] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the German version of the Christmas hymn Dies est latitiae with the English translation by Charles Sanford Terry.

|

|

The melody, medieval in origin, was published with the text in 1529. Apart from BWV 606, Bach composed a harmonisation of the hymn in BWV 294 and set it as a chorale prelude, BWV 719 in the Neumeister Collection. The chorale prelude BWV 605 is written for two manuals and pedal with the cantus firmus in the soprano part. The frequent F♮s are a hint of the mixolydian mode. The accompanying motif is shared between the two inner voices on the second manual which together provide a continuous stream of semiquavers with two hemidemiquavers on the second semiquaver of each group. The pedal provides a rhythmic pulse with a semiquaver walking bass with sustained notes at each cadence. Williams (2003) suggests that the relative simplicity of BWV 605 and the uniformity of the accompaniment could be signs that it was one of the earliest composed pieces in Orgelbüchlein. Dissonances in the pedal in bars 3 and 5, however, could also be signs of Bach's more mature style. Ernst Arfken and Siegfried Vogelsänger have interpreted some of the dissonant F♮s as references to elements of foreboding in the text (for example Ei du süsser Jesu Christ in the second verse). The accompanying figure in the inner voices has been interpreted as a joy motif by Schweitzer (1905); as an evocation of rocking by Keller (1948); and as symbolising the miracle of virgin birth by Arfken. Many commentators have agreed with Spitta (1899) that the lively and rhythmic accompaniment conveys "Christmas joy".[11][12]

- BWV 606 Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her [From Heaven on high I come here]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first, second and last verses of the Christmas hymn Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her by Martin Luther with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The melody of Vom Himmel hoch was published in 1539. The hymn was performed throughout the Christmas period, particularly during nativity plays. Many composers set it to music for both chorus and organ: closest to Bach's time, Pachelbel and Johann Walther [13] wrote chorale preludes. Bach's use of the hymn in his choral works includes the Magnificat, BWV 243 and 3 settings in the Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248. Apart from BWV 606, his organ settings include the early chorale preludes BWV 701 and 702 from the Kirnberger Collection and BWV 738 from the Neumeister Collection; the five Canonic Variations, BWV 769 were composed towards the end of his life.

The chorale prelude BWV 606 is written for single manual and pedal with the cantus firmus in the soprano part. As in all his other organ settings, Bach changed the rhythmic structure of the melody by drawing out the initial upbeats to long notes. This contrasts with Bach's choral settings and the chorale preludes of Pachelbel and Walther, which follow the natural rhythm of the hymn. In BWV 606, the rhythm is further obscured by the cadences of the second and final lines falling on the third beat of the bar. The accompaniment on the keyboard is built from semiquaver motifs, made up of four-note groups of suspirans semiquavers (starting with a rest or "breath"). These include turning figures and ascending or descending scales all presented in the first bar. The semiquaver figures, sometimes in parallel thirds or sixths, run continuously throughout the upper parts, including the soprano part, further obscuring the melody. Below the upper voices, there is a striding pedal part in quavers with alternate footing. In the two closing bars, there is a fleeting appearance of figures usually associated with crucifixion chorales, such as Da Jesu an dem Kreuzer stund, BWV 621: semiquaver cross motifs[14] in the upper parts above delayed or dragging entries in the pedal.

The predominant mood of the chorale prelude is one of joyous exultation. The semiquaver motifs, in constant motion upwards and downwards, create what Schweitzer (1905) called "a charming maze," symbolising angels heralding the birth of Christ. As Anton Heiller and others have observed, the brief musical allusions to the crucifixion in the closing bars bring together themes from Christmas and Easter, a momentary reminder that Christ came into the world to suffer; in the words of Clark & Peterson (1984), "Christ's Incarnation and Passion are inseparable, and Bach tried to express this through musical means." [15][16][17][18]

- BWV 607 Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar [From Heaven came the host of angels]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and fourth verses of Martin Luther's Christmas hymn with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The cantus firmus of this chorale prelude is in the soprano voice and is drawn from the tenor part of the four-part setting of Puer natus by Lossius. It is the only time Bach that used this hymn tune. Although there is some ambiguity in the autograph manuscript, the crossing of parts suggests that the intended scoring is for single manual and pedals. The motifs in the intricately crafted accompaniment are descending and ascending scales, sometimes in contrary motion, with rapid semiquaver scales shared between the inner voices and slower crotchet scales in the walking bass of the pedal part following each phrase of the melody. The mood of the chorale prelude is "ethereal" and "scintillating", veering elusively between the contemplative harmonised melody and the transitory rushing scales: towards the close the scales in the inner voices envelope the melody. The semiquaver motifs have been taken to represent flights of angels in the firmament: for Spitta (1899), "Bach's music rushes down and up again like the descending and ascending messengers of heaven."[19][20]

- BWV 608 In dulci jubilo [In sweet joy]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the traditional fourteenth century German/Latin Christmas carol In dulci jubilo with the English/Latin translation of Robert Lucas de Pearsall.

|

|

This chorale prelude is based on a traditional Christmas carol in canon that predates Luther. Prior to Bach, there had been settings of the carol as a canon by Fridolin Sicher and Johann Walther for organ and by Michael Praetorius for choir. Bach's chorale prelude is written for single manual and pedals, with the leading voice in the soprano. The canon—normally in the tenor part in the carol—is taken up one bar later in the pedal. As was Bach's custom, it was notated in the autograph manuscript at the pitch at which it should sound, although this fell outside the range of baroque pedalboards. The desired effect was achieved by using a 4' pedal stop, playing the pedals an octave lower. The two accompanying inner voices, based on a descending triplet motif, are also in canon at the octave: such a double canon is unique amongst Bach's organ chorales. Following baroque convention, Bach notated the triplets in the accompaniment as quavers instead of crotchets, to make the score more readable for the organist. The accompaniment also has repeated crotchets on the single note of A, which, combined with the A's in the main canon, simulate the drone of a musette sounding constantly through the chorale until the A♯ in bar 25. At that point the strict canon in the accompaniment stops, but the imitative triplet motif continues until the close, also passing effortlessly into the soprano part. Over the final pedal point, it sounds in all three of the upper voices. There is some ambiguity as to whether Bach intended the crotchets in the accompanying motif to be played as a dotted rhythm in time with the triplets or as two beats against three. The deliberate difference in spacing in the autograph score and the intended drone-like effect might suggest adopting the second solution throughout, although modern editions often contain a combination of the two.

The piping triplets above the musette drone create a gentle pastoral mood, in keeping with the subject of the carol. For Williams (2003) the constant sounding of A major chords, gently embellished by the accompaniment, suggest unequivocally the festive spirit of the dulci and jubilo in the title; Schweitzer (1905) already described the accompanying triplets as representing a "direct and naive joy." Williams further suggests that the F♯ major chord at bar 25 might be a reference to leuchtet als die Sonne ("shines like the sun") in the first verse; and the long pedal point at the close to Alpha es et Omega ("You are the Alpha and the Omega") at the end of the first verse. The mood also reflects the first two lines of the third verse, "O love of the father, O gentleness of the newborn!" Bach often used canons in his chorale preludes to signify the relation between "leader" and "follower" as in his settings of Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot ("These are the Ten Commandments"); Stinson (1999) considers that this was unlikely to be the case here, despite the words Trahe me post te ("Draw me to thee") in the second verse.[21][22]

- BWV 609 Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich [Praise God, you Christians all together]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of Nikolaus Herman's Christmas hymn with the English translation by Arthur Russell.

|

|

The melody first appeared with this text in a 1580 hymnbook. Prior to Bach, there were choral settings by Michael Praetorius and Samuel Scheidt and a setting for organ in the choral prelude BuxWV 202 by Dieterich Buxtehude. Apart from BWV 609, Bach set the hymn in the cantatas BWV 151 and 195, the two harmonisations BWV 375 and 376 and the chorale prelude BWV 732. The chorale prelude BWV 609 is scored for single manual and pedal with the cantus firmus unembellished in the soprano voice. The accompaniment in the inner voices is a uniform stream of semiquavers shared between the parts, often in parallel sixths but occasionally in contrary motion. It is built up from several four-note semiquaver motifs first heard in the opening bars. Beneath them in the pedal is a contrasting walking bass in quavers with sustained notes at the end of each phrase. Unlike the inner voices, the pedal part has a wide range: there are two scale-like passages where it rises dramatically through two octaves, covering all the notes from the lowest D to the highest D. The four voices together convey a mood of joyous exultation. Stinson (1999) speculates that the passages ascending through all the notes of the pedalboard might symbolise the word allzugleich ("all together"); and Clark & Peterson (1984) suggest that the widening intervals at the start between the cantus and the descending pedal part might symbolise the opening up of the heavens (schließt auf sein Himmelreich).[23][24]

- BWV 610 Jesu, meine Freude [Jesus, my joy]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first two verses of Johann Frank's hymn Jesu, meine Freude with the English translation by Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The melody was first published with the text in Johann Crüger's hymnal Praxis pietatis melica of 1653. In later hymnbooks the hymn became associated with Christmas and Epiphany; it was also frequently included amongst the so-called Jesuslieder, devotional hymns addressed to Jesus, often for private use. One of the earliest settings of the hymn was Dieterich Buxtehude's cantata BuxWV 60 for four voices, strings and continuo, composed in the 1680s. Bach's friend and colleague Johann Walther composed an organ partita on the hymn in 1712. Apart from BWV 610, Bach's organ settings include the chorale preludes BWV 713 in the Kirnberger Collection, BWV 1105 in the Neumeister Collection and BWV 753 composed in 1720. Amongst his choral settings are the harmonisation BWV 358, the motet BWV 227 for unaccompanied choir and cantatas BWV 12, 64, 81 and 87.

The chorale prelude BWV 610 is scored for single manual and pedal, with the cantus firmus unadorned in the soprano voice. Marked Largo, the cantus and accompanying voices in the two inner parts and pedal are written at an unusually low pitch, creating a sombre effect. The accompaniment is based on semiquaver motifs first heard in their entirety in the pedal in bar one; the inner parts often move in parallel thirds followed by quasi-ostinato responses in the pedal. The rich and complex harmonic structure is partly created by dissonances arising from suspensions and occasional chromaticisms in the densely scored accompanying voices: the motifs are skillfully developed but with restraint.

Both Williams (2003) and Stinson (1999) concur with the assessment of Spitta (1899) that "fervent longing (sehnsuchtsvoll Innigkeit) is marked in every line of the exquisite labyrinth of music in which the master has involved one of his favourite melodies." As Honders (1988) has pointed out, when composing this chorale prelude Bach might have had in mind one of the alternative more intimate texts for the melody such as Jesu, meine Freude, wird gebohren heute, available in contemporary Weimar hymnbooks and reprinted later in Schemellis Gesangbuch of 1736.[25][26]

- BWV 611 Christum wir sollen loben schon [We should indeed praise Christ] Choral in Alto

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Martin Luther's hymn Christum wir sollen loben schon with the original Latin text A solis ortus cardine of Coelius Sedulius and the English translation of Charles Kinchen.

|

|

|

- BWV 612 Wir Christenleut [We Christians]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and third verses of the hymn of Caspar Fuger with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

New Year BWV 613–615

* BWV 613 Helft mir Gotts Güte preisen [Help me to praise God's goodness] ![]() play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of this New Year's hymn of Paul Eber with the English translation by John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

* BWV 614 Das alte Jahr vergangen ist [The old year has passed] a 2 Clav. et Ped. ![]() play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the six verses of this New Year's hymn with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

Customarily sung on New Year's Day, the hymn addresses thanks for the past year and prayers for the coming year to Christ. Although primarily a supplication looking forwards to the future, the hymn also looks back at the past, reflecting on the perils facing man, his sins and his transitory existence.

The version of the hymn that Bach used for BWV 614 only emerged gradually. The first two verses of the hymn text were first published in Clemens Stephani's Nuremberg hymnbook of 1568; the entire six verses of the text appeared in Johann Steuerlein's Erfurt hymnbook of 1588. An early version of the melody also appeared in Steuerlein's hymnbook, but set to different words (Gott Vater, der du deine Sonn). That melody first appeared with the text in Erhard Bodenschatz's Leipzig hymnbook of 1608. One of the earliest known sources for the version of the hymn used by Bach is Gottfried Vopelius's Leipzig hymnbook of 1682. Prior to modern scientific methods for dating Bach's autograph manuscripts, scholars had relied on identifying hymnbooks available to him to determine exactly when Orgelbüchlein was written. Terry (1921) erroneously assigned a date after 1715, because the earliest source for Das alte Jahr he had been able to locate was Christian Friedrich Witt's Gotha hymnbook, first published in 1715. As is now known, Bach set Das alte Jahr early in his career as BWV 1091, one of the chorale preludes in the Neumeister Collection; he also composed two four-part harmonisations, BWV 288 and 289.[27][28][29][30]

The chorale prelude BWV 614 is written for two manuals and pedal with the cantus firmus in the soprano voice. Despite starting starkly with two repeated crotchets—unaccompanied and unembellished—in the cantus, BWV 614 is an ornamental chorale prelud: the highly expressive melodic line, although restrained, includes elaborate ornamentation, coloratura melismas (reminiscent of Bach's Arnstadt chorale preludes) and "sighing" falling notes, which at the close completely subsume the melody as they rise and fall in the final cadence. The accompaniment is built from the motif of a rising chromatic fourth heard first in the response to the first two notes of the cantus. The motif is in turn linked to the melodic line, which later on in bar 5 is decorated with a rising chromatic fourth. Bach ingeniously develops the accompaniment using the motif in canon, inversion and semiquaver stretto. The three lower voices respond to each other and to the melodic line, with the soprano and alto voices sighing in parallel sixths at the close. The chromatic fourth was a common form of the baroque passus duriusculus, mentioned in the seventeenth century musical treatise of Christoph Bernhard, a student of Heinrich Schütz. The chromaticism creates ambiguities of key throughout the chorale prelude. The original hymn melody is in the aeolian mode of A (the natural form of A minor) modulating to E major in the final cadence. Renwick (2006) analyses the mysteries of the key structure in BWV 614. In addition to giving a detailed Schenkerian analysis, he notes that the cadences pass between D minor and A until the final cadence to E major; that the modal structure moves between the Dorian mode on D and the Phrygian mode on E through the intermediary of their common reciting note A; and that the key changes are mediated by the chromatic fourths in the accompaniment.[31][32][33][34]

Since the nineteenth century successive commentators have found the mood of the chorale prelude to be predominantly sad, despite that not being in keeping with the hymn text. The chromatic fourth has been interpreted as a "grief motif". It has been described as "melancholic" by Schweitzer (1905); as having "the greatest intensity" by Spitta (1899); as a "prayer" with "anxiety for the future" by Ernst Arfken; and as a crossroads between "the past and the future" by Jacques Chailley. Williams (2003) suggests that the grieving mood might possibly reflect tragic events in Bach's life at the time of composition; indeed in 1713 his first wife gave birth to twins who died within a month of being born. Renwick (2006) takes a different approach, suggesting that Bach's choice of tonal structure leads the listener to expect the E's that end the chorale prelude to be answered by A's, the notes that start it. To Renwick such "cyclicity" reflects the themes of the hymn: "a turning point; a Janus-like reflection backward and forward; regret for the past and hope for the future; the place between before and after." [35][36][37]

* BWV 615 In dir ist Freude [In you is joy] ![]() play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of this hymn of Johann Lindemann with the English translation by Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

Lindemann wrote the text in 1598, and Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi supplied the melody in 1591.[38]

Epiphany BWV 616–617

- BWV 616 Mit Fried' und Freud' ich fahr' dahin [With peace and joy I depart]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Martin Luther's version of the Nunc dimittis, Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin, with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

- BWV 617 Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf [Lord God, now unlock Heaven]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of Tobias Kiel's hymn with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

Lent BWV 618–624

- BWV 618 O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig [Oh innocent Lamb of God] Canon alla Quinta

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse and refrain of the third verse of this version of the Agnus Dei, O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig, with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

- BWV 619 Christe, du Lamm Gottes [Christ, Lamb of God] in Canone alla Duodecime, a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse and refrain of the third verse of Christe, du Lamm Gottes, a German version of the Agnus Dei, with the English translation of Charles Sanford Terry.

|

|

- BWV 620 Christus, der uns selig macht [Christ, who makes us blessed] in Canone all'Ottava

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the first and last verse of the Passiontide hymn with the English translation of John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

- BWV 621 Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund [As Jesus hung upon the Cross]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the first and last verses of the Passiontide hymn with the English translation of Charles Sanford Terry.

|

|

- BWV 622 O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß [Oh Man, bewail your great sins] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the first stanza of the hymn O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß by Sebald Heyden with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

"O Mensch" is one of the most celebrated of Bach's chorale preludes. The cantus firmus, composed in 1525 by Matthias Greitter and associated with Whitsuntide, was also later used with the same words for the closing chorale of the first part of the St Matthew Passion, taken from the 1725 version of the St John Passion. Bach ornamented the simple melody, in twelve phrases reflecting the twelve lines of the opening verse, with an elaborate coloratura. It recalls but also goes beyond the ornamental chorale preludes of Buxtehude. The ornamentation, although employing coventional musical figures, is highly original and inventive. While the melody in the upper voice is hidden by coloratura over a wide range, the two inner voices are simple and imitative above the continuo-style bass. Bach varies the texture and colouring of the accompaniment for each line of what is one of the longest melodies in the collection.

In the penultimate line, accompanying the words "ein schwere Bürd" (a heavy burden), the inner parts intensify moving in semiquavers (16th notes) with the upper voice to a climax on the highest note in the prelude. The closing phrase, with its mounting chromatic bass accompanying bare unadorned crotchets (quarter notes) in the melody to end in an unexpected modulation to C♭ major, recall but again go beyond earlier compositions of Pachelbel, Frohberger and Buxtehude. It has been taken by some commentators as a musical allusion to the words kreuze lange in the text: for Spitta the passage was "full of imagination and powerful feeling." As Williams (2003) comments, however, the inner voices, "with their astonishing accented passing-notes transcend images, as does the sudden simplicity of the melody when the bass twice rises chromatically."

- BWV 623 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ [We give thanks to you, Lord Jesus Christ]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the hymn with the English translation of Benjamin Hall Kennedy.

|

|

- BWV 624 Hilf, Gott, daß mir's gelinge [Help me, God, that I may succeed] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the hymn with an English translation of the period.

|

|

Easter BWV 625–630

- BWV 625 Christ lag in Todesbanden [Christ lay in the bonds of death]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and fourth verses of Martin Luther's Easter hymn Christ lag in Todesbanden with the English translation of Paul England.[39]

|

|

BWV 625 is based on the hymn tune of Luther's "Christ lag in Todesbanden". The sharp on the second note was a more modern departure, already adopted by the composer-organists Bruhns, Böhm and Scheidt and by Bach himself in his early cantata Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4.[40] The chorale prelude is in four parts for single manual and pedals, with the cantus firmus in the soprano voice. It closely follows the four voices of Bach's earlier harmonisation in the four-part chorale BWV 278, with virtually no changes in the cantus firmus.[41] The two accompanying inner parts and pedal are elaborated by a single motif of four or eight semiquavers descending in steps. It is derived from the final descending notes of the melody:

The semiquaver motif runs continuously throughout the piece, passing from one lower voice to another. Commentators have given different interpretations of what the motif might symbolise: for Schweitzer (1905) it was "the bonds of death" (Todesbanden) and for Hermann Keller "the rolling away of the stone". Some have also seen the suspensions between bars as representing "the bonds of death". These interpretations can depend on the presumed tempo of the chorale prelude. A very slow tempo was adopted by the school of late nineteenth and early twentieth century French organists, such as Guilmant and Dupré: for them the mood of the chorale prelude was quiet, inward-looking and mournful; Dupré even saw in the descending semiquavers "the descent by the holy women, step by step, to the tomb". At a faster tempo, as has become more common, the mood becomes more exultant and vigorous, with a climax at the words Gott loben und dankbar sein ("praise our God right heartily"), where the music becomes increasingly chromatic. Williams (2003) suggests that the motif might then resemble the Gewalt ("power") motif in the cello part of BWV 4, verse 3; and that the turmoil created by the rapidly changing harmonies in some bars might echo the word Krieg ("war") in verse 4.[42][43]

- BWV 626 Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der den Tod überwand [Jesus Christ, our Saviour, who conquered death]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Martin Luther's Easter hymn Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der den Tod überwand with the English translation by George MacDonald.

|

|

- BWV 627 Christ ist erstanden [Christ is risen]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the text of the three verses of the Easter hymn Christ ist erstanden with the English translation of Myles Coverdale.

|

|

- BWV 628 Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ [The holy Christ is risen]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the traditional Easter carol Surrexit Christus hodie in German and English translations.

|

|

- BWV 629 Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag [The glorious day has come] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Nikolaus Herman's hymn with the English translation of Arthur Russell.

|

|

- BWV 630 Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn [Today the Son of God triumphs]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Caspar Stolshagen's Easter hymn Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn by Bartholomäus Gesius with the English translation of George Ratcliffe Woodward.

|

|

Pentecost BWV 631–634

- BWV 631 Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist [Come God, Creator, Holy Ghost]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of Martin Luther's hymn for Pentecost Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist with the English translation of George MacDonald.

|

|

- BWV 632 Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend [Lord Jesus Christ, turn to us]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and third verses of this hymn by William, Duke of Saxe-Weimar with the English translation of John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

- BWV 633 Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (distinctius) [Dearest Jesus, we are here] in Canone alla Quinta, a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

- BWV 634 Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier [Dearest Jesus, we are here] in Canone alla Quinta, a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI

play MIDI

Below is the first verse of Tobias Clausnitzer's hymn with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

Catechism hymns BWV 635–638

- BWV 635 Dies sind die heil'gen zehn Gebot [These are the ten commandments]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last two verses of the Lutheran catechism hymn of the Ten Commandments with an English translation by George MacDonald.

|

|

The Lutheran Erfurter Enchiridion of 1524 contains the text with the melody, which was also used for In Gottes Nahmen fahren wir, a pilgrims' hymn. Bach wrote a four-part chorale on the hymn tune in BWV 298; he used it for the trumpet canon in the opening chorus of cantata BWV 77; and much later he set it for organ in the first two of the catechism chorale preludes, BWV 678 and 679, of Clavier-Übung III.

The chorale prelude BWV 635 is in the mixolydian mode with the cantus firmus in the soprano voice in simple minims. The accompaniment in the three lower voices is built up from two motifs each containing the repeated notes that characterise the theme. The first motif in quavers is a contracted version of the first line of the cantus (GGGGGGABC), first heard in the pedal bass in bars 1 and 2. It also occurs in inverted form. This emphatic hammering motif is passed imitatively between the lower voices as a form of canon. The second motif, first heard in the alto part in bars 2 and 3, is made up of five groups of 4 semiquavers, individual groups being related by inversion (first and fifth) and reflection (second and third). The pivotal notes CCCDEF in this motif are also derived from the theme. The second motif is passed from voice to voice in the accompaniment—there are two passages where it is adapted to the pedal with widely spaced semiquavers alternating between the feet—providing an unbroken stream of semiquavers complementing the first motif.

The combined affekt of the four parts, with 25 repetitions of the quaver motif, is one of "confirming" the biblical laws chanted in the verses of the hymn. There is likewise a reference to "law" in the canon of the quaver motif. For Spitta (1899) the motif had "an inherent organic connection with the chorale itself." Some commentators, aware that the number "ten" of the Ten Commandments has been detected in the two chorale preludes of Clavier-Übung III, have endeavoured to find a hidden numerology in BWV 635. The attempts of Schweitzer (1905) have been criticised: Harvey Grace felt that Bach was "expressing the idea of insistence, order, dogma—anything but statistics." Williams (2003) points out, however, that if there is any intentional numerology, it might be in the occurrences of the strict form of the motif, with tone and semitone intervals matching the first entry: it occurs precisely ten times in the chorale prelude (b1 – bass; b1 – tenor; b2 – bass; b4 – bass; b9 – tenor; b10 – bass; b11 – tenor; b13 – tenor; b15 – alto; b18 – tenor).[44][45]

- BWV 636 Vater unser im Himmelreich [Our Father who art in Heaven]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of the Lutheran version of the Lord's Prayer with the English translation of George MacDonald.

|

|

Following the publication of the text and melody in 1539, the hymn was used in many choral and organ compositions. Amongst Bach's immediate predecessors, Dieterich Buxtehude wrote two settings of the hymn for organ—a freely composed chorale prelude in three verses (BuxWV 207) and a chorale prelude for two manuals and pedal (BuxWV 219); and Georg Böhm composed a partita and two chorale preludes (previously misattributed to Bach as BWV 760 and 761). Bach himself harmonised the hymn in BWV 416, with a later variant in one of the chorales from the St John Passion. He used it in cantatas BWV 90, 100 and 102 with a different text. Amongst the early organ compositions on Vater unser attributed to Bach, only the chorale prelude BWV 737 has been ascribed with any certainty. After Orgelbüchlein, Bach returned to the hymn with a pair of chorale preludes (BWV 682 and 683) in Clavier-Übung III.

In the chorale prelude BWV 636 the plain cantus firmus is in the soprano voice. The accompaniment in the inner parts and pedal is based on a four-note semiquaver suspirans motif (i.e. preceded by a rest or "breath") and a longer eight-note version; both are derived from the first phrase of the melody. In turn Bach's slight alteration of the melody in bars 1 and 3 might have been dictated by his choice of motif. The two forms of the motif and their inversions pass from one lower voice to another, producing a continuous stream of semiquavers; semiquavers in one voice are accompanied by quavers in the other two. The combined effect is of the harmonisation of a chorale by arpeggiated chords. Hermann Keller even suggested that Bach might have composed the chorale prelude starting from an earlier harmonisation; as Williams (2003) points out, however, although the harmonic structure adheres to that of a four-part chorale, the pattern of semiquavers and suspended notes is different for each bar and always enhances the melody, sometimes in unexpected ways. Schweitzer (1905) described the accompanying motifs as representing "peace of mind"(quiétude).[46][47][48]

- BWV 637 Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt [Through Adam's fall are wholly ruined]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and seventh verses of the hymn written in 1524 by Lazarus Spengler with an English translation by John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

The penitential text, written in the Nuremberg of Hans Sachs and the Meistersingers where Spengler was town clerk, is concerned with "human misery and ruin," faith and redemption; it encapsulates some of the central tenets of the Lutheran Reformation. The melody, originally for a Reformation battle hymn of 1525, was first published with Spengler's text in 1535. Bach previously set it as a chorale prelude in the Kirnberger Collection (BWV 705) and Neumeister Collection (BWV 1101); the seventh verse also recurs in the closing chorales of cantatas BWV 18 and BWV 109. Dieterich Buxtehude had already set the hymn as a chorale prelude (BuxWV 183) prior to Bach.

The chorale prelude BWV 637 is one of the most original and imaginative in the Orgelbüchlein, with a wealth of motifs in the accompaniment. Scored for single manual and pedal, the unadorned cantus firmus is in the soprano voice. Beneath the melody in a combination of four different motifs, the inner parts wind sinuously in an uninterrupted line of semiquavers, moving chromatically in steps. Below them the pedal responds to the melodic line with downward leaps in diminished, major and minor sevenths, punctuated by rests. Bach's ingenious writing is constantly varying. The expressive mood is heightened by the fleeting modulations between minor and major keys; and by the dissonances between the melody and the chromatic inner parts and pedal. The abrupt leaps in the pedal part create unexpected changes in key; and halfway through the chorale prelude the tangled inner parts are inverted to produce an even stranger harmonic texture, resolved only in the final bars by the modulation into a major key.

The chorale prelude has generated numerous interpretations of its musical imagery, its relation to the text and to baroque affekt. Williams (2003) records that the dissonances might symbolise original sin, the downward leaps in the pedal the fall of Adam, and the modulations at the close hope and redemption; the rests in the pedal part could be examples of the affekt that the seventeenth century philosopher Athanasius Kircher called "a sighing of the spirit." Stinson (1999) points out that the diminished seventh interval used in the pedal part was customarily associated with "grief." The twisting inner parts have been interpreted as illustrating the words verderbt ("ruined") by Hermann Keller and Schlang ("serpent") by Jacques Chailley. Terry (1921) described the pedal part as "a series of almost irremediable stumbles"; in contrast Ernst Arfken saw the uninterrupted cantus firmus as representing constancy in faith. For Wolfgang Budday, Bach's departure from normal compositional convention was itself intended to symbolise the "corruption" and "depravity" of man. Spitta (1899) also preferred to view Bach's chorale prelude as representing the complete text of the hymn instead of individual words, distinguishing it from Buxtehude's earlier precedent. Considered to be amongst his most expressive compositions—Snyder (1987) describes it as "imbued with sorrow"—Buxtehude's setting employs explicit word-painting.[49][50][51]

- BWV 638 Es ist das Heil uns kommen her [Salvation has come to us]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

The first verse of the Lutheran hymn Es ist das Heil uns kommen her of Paul Speratus is given below with the English translation of John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

The text treats a central Lutheran theme—only faith in God is required for redemption. The melody is from an Easter hymn. Many composers had written organ settings prior to Bach, including Sweelinck, Scheidt and Buxtehude (his chorale prelude BuxWV 186). After Orgelbüchlein, Bach set the entire hymn in cantata Es ist das Heil uns kommen her, BWV 9; and composed chorales on single verses for cantatas 86, 117, 155 and 186.

In the chorale prelude BWV 638 for single manual and pedal, the cantus firmus is in the soprano voice in simple crotchets. The accompaniment in the inner voices is built on a four-note motif—derived from the hymn tyne—a descending semiquaver scale, starting with a rest or "breath" (suspirans): together they provide a constant stream of semiquavers, sometimes in parallel sixths, running throughout the piece until the final cadence. Below them the pedal is a walking bass in quavers, built on the inverted motif and octave leaps, pausing only to mark the cadences at the end of each line of the hymn. The combination of the four parts conveys a joyous mood, similar to that of BWV 606 and 609. For Hermann Keller, the running quavers and semiquavers "suffuse the setting with health and strength." Stinson (1999) and Williams (2003) speculate that this chorale prelude and the preceding BWV 637, written on opposite sides of the same manuscript paper, might have been intended as a pair of contrasting catechism settings, one about sin, the other about salvation. Both have similar rhythmic structures in the parts, but one is in a minor key with complex chromatic harmonies, the other in a major key with firmly diatonic harmonies.[52][53]

Miscellaneous BWV 639–644

- BWV 639 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ [I call to you, Lord Jesus Christ] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of Johann Agricola's hymn with the English translation of John Christian Jacobi.

|

|

"Ich ruf zu dir" is amongst the most popular chorale preludes in the collection. Pure in style, this ornamental chorale prelude has been described as "a supplication in time of despair." Written in the meantone key of F minor, it is the unique prelude in trio form with voices in the two manuals and the pedal. It is possible that the unusual choice of key followed Bach's experience playing the new organ at Halle which employed more modern tuning. The ornamented melody in crotchets (quarter notes) sings in the soprano above a flowing legato semiquaver (16th note) accompaniment and gently pulsating repeated quavers (eighth notes) in the pedal continuo. Such viol-like semiquaver figures in the middle voice already appeared as "imitatio violistica" in the Tabalutara nova (1624) of Samuel Scheidt. The instrumental combination itself was used elsewhere by Bach: in the third movement of the cantata Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele, BWV 180 for soprano, violoncello piccolo and continuo; and the 19th movement of the St John Passion, with the middle voice provided by semiquaver arpeggios on the lute.

- BWV 640 In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr [In you have I put my hope, Lord]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below is the first verse of the hymn of Adam Reissner with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The text of the hymn is derived from the first six lines of Psalm 31 and was associated with two different melodies, in major and minor keys. The hymn tune in the major key was used many times by Bach, most notably in the funeral cantata BWV 106, the Christmas Oratorio and the St. Matthew Passion. BWV 640 is the only occasion he used the melody in the minor key, which can be traced back to an earlier reformation hymn tune for Christ ist erstanden and medieval plainsong for Christus iam resurrexit.

In Bach's chorale prelude BWV 640, the cantus firmus is in the soprano voice, several times held back for effect. Beneath it the two inner voices—often in thirds—and the pedal provide an accompaniment based on a motif derived from the melody, a falling three-note anapaest consisting of two semiquavers and a quaver. The motif is passed imitatively down through the voices, often developing into more flowing passages of semiquavers; the motif in the pedal has an added quaver and—punctuated by rests—is more fragmentary. The harmonies resulting from the combined voices produce a hymn-like effect. Schweitzer (1905) described the anapaest as a "joy" motif; to Hermann Keller it symbolised "constancy". For Williams (2003), the angular motifs and richer subdued textures in the lower registers are consonant with the "firm hope" of the text, in contrast to more animated evocations of joy.[54][55]

- BWV 641 Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein [When we are in the greatest distress] a 2 Clav. et Ped.

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first two verses of the hymn of Paul Eber with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The cantus firmus of this ornamental chorale prelude was written by Louis Bourgeois in 1543. It was used again the last of the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes, BWV 668. The accompaniment in the two middle voices, often in parallel sixths, and the pedal is derived from the first four notes of the melody. The highly ornate ornamentation is rare amongst Bach's chorale preludes, the only comparable example being BWV 662 from the Great Eighteen. The vocal ornamentation and portamento appoggiaturas of the melody are French in style. Coloratura passages lead into the unadorned notes of the cantus firmus. Williams (2003) describes this musical device, used also in BWV 622 and BWV 639, as a means of conveying "a particular kind of touching, inexpressible expressiveness." The prelude has an intimate charm: as Albert Schweitzer commented, the soprano part flows "like a divine song of consolation, and in a wonderful final cadence seems to silence and compose the other parts."

- BWV 642 Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten [He who allows dear God to lead him]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of the hymn Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten of Georg Neumark with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

The melody was also composed by Neumark: it and the text were first published in his hymn book of 1657. The hymn tune was later set to other words, notably Wer weiss, wie nahe mir mein Ende ("Who knows how near is my end?"). Neumark originally wrote the melody in 3/2 time. Bach, however, like Walther, Böhm and Krebs, generally preferred a version in 4/4 time for his fourteen settings in chorale preludes and cantatas: it appears in cantatas BWV 21, BWV 27, BWV 84, BWV 88, BWV 93, BWV 166, BWV 179 and BWV 197, with words taken from one or other of the two hymn texts. In the chorale prelude BWV 642, the unadorned cantus firmus in 4/4 time is in the soprano voice. The two inner voices, often in thirds, are built on a motif made up of two short beats followed by a long beat—an anapaest—often used by Bach to signify joy (for example in BWV 602, 605, 615, 616, 618, 621, 623, 627, 629, 637 and 640). The pedal has a walking bass which also partly incorporates the joy motif in its responses to the inner voices. For Schweitzer (1905) the accompaniment symbolised "the joyful feeling of confidence in God's goodness." BWV 642 has similarities with the earlier chorale prelude BWV 690 from the Kirnberger collection, with the same affekt of a delayed entry in the second half of the cantus firmus. The compositional structure for all four voices in BWV 642 is close to that of BWV 643.[56][57]

- BWV 643 Alle Menschen müssen sterben [All mankind must die]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last two verses of the funeral hymn of Johann Georg Albinus with the English translation of Catherine Winkworth.

|

|

BWV 643 is one of the most perfect examples of Bach's Orgelbüchlein style. A mood of ecstasy permeates this chorale prelude, a funeral hymn reflecting the theme of heavenly joy. The simple cantus firmus sings in crotchets (quarter notes) above an accompanying motif of three semiquavers (16th notes) followed by two quavers (eighth notes) that echoes between the two inner parts and the pedal. This figure is also found in the organ works of Georg Böhm and Daniel Vetter from the same era. Schweitzer (1905) describes its use by Bach as a motif of "beatific peace", commenting that "the melody of the hymn that speaks of the inevitability of death is thus enveloped in a motif that is lit up by the coming glory." Despite the harmonious thirds and sixths in the inner parts, the second semiquaver of the motif produces a momentary dissonance that is instantly resolved, again contributing to the mood of joy tinged by sadness. As Spitta (1899) comments, "What tender melancholy lurks in the chorale, Alle Menschen müßen sterben, what an indescribable expressiveness, for instance, arises in the last bar from the false relation between c♯ and c', and the almost imperceptible ornamentation of the melody!"

- BWV 644 Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig [Oh how fleeting, oh how feckless]

play MIDI • play MP3

play MIDI • play MP3

Below are the first and last verses of Michael Franck's hymn of 1652 with the English translation of Sir John Bowring.

|

|