Bắc Lệ ambush

| Bac Le ambush | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tonkin Campaign | |||||||

The Bac Le ambush, 23 June 1884 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 450 French troops, 350 Tonkinese auxiliaries | 4,600 Chinese regulars | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 22 killed, 70 wounded | around 300 killed and wounded | ||||||

The Bac Le ambush (French: guet-apens de Bac-Lé, Vietnamese: trận Bắc Lệ or trận cầu Quan Âm) was a clash during the Tonkin Campaign in June 1884 between Chinese troops of the Guangxi Army and a French column sent to occupy Lang Son and other towns near the Chinese border.[4] The French claimed that their troops had been ambushed by the Chinese. The incident led to the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).

Background

In late 1883 France and China began to fight an undeclared war in Tonkin. In December 1883, in the Son Tay Campaign, the French defeated the Black Flag Army and captured the town of Son Tay. In March 1884, in the Bac Ninh campaign, they defeated China's Guangxi Army and captured the strategically important town of Bac Ninh on the Mandarin Road.

The defeat at Bac Ninh, coming close on the heels of the fall of Son Tay, strengthened the hand of the moderate element in the Chinese government and temporarily discredited the extremist 'Purist' party led by Zhang Zhidong, which was agitating for a full-scale war against France. Further French successes in the spring of 1884, including the capture of Hung Hoa and Thai Nguyen, convinced the Empress Dowager Cixi that China should come to terms, and an accord was reached between France and China in May. The negotiations took place in Tianjin (Tientsin). Li Hongzhang, the leader of the Chinese moderates, represented China; and Captain François-Ernest Fournier, commander of the French cruiser Volta, represented France. The Tientsin Accord, concluded on 11 May 1884, provided for a Chinese troop withdrawal from Tonkin in return for a comprehensive treaty that would settle details of trade and commerce between France and China and provide for the demarcation of its disputed border with Vietnam.

Fournier was not a professional diplomat, and the Tientsin Accord contained several loose ends. Crucially, it failed to explicitly state a deadline for the Chinese troop withdrawal from Tonkin. The French asserted that the troop withdrawal was to take place immediately, while the Chinese argued that the withdrawal was contingent upon the conclusion of the comprehensive treaty. In fact, the Chinese stance was an ex post facto rationalisation, designed to justify their unwillingness or inability to put the terms of the accord into effect. The accord was extremely unpopular in China, and provoked an immediate backlash. The war party called for Li Hongzhang's impeachment, and his political opponents intrigued to have orders sent to the Chinese troops in Tonkin to hold their positions.[5]

Li Hongzhang hinted to the French that there might be difficulties in enforcing the accord, but nothing specific was said. The French assumed that the Chinese troops would leave Tonkin as agreed, and made preparations for occupying Lang Son and other cities up to the Chinese border.

The approach march

In early June 1884 a French column under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alphonse Dugenne advanced to occupy the border towns of Lang Son, Cao Bang and That Khe. Dugenne's column consisted of a battalion of marine infantry (chef de bataillon Reygasse), an artillery battery (Captain Jourdy), a newly recruited company of Tonkinese riflemen, and a small force of chasseurs d'Afrique (Captain Laperrine).[Note 1] Reygasse's marsouins were veteran soldiers, who had served under the command of Commandant Henri Rivière at the Capture of Nam Dinh (March 1883), but the Tonkinese riflemen had only been recruited several days earlier, and were of negligible military value. The column needed to take food and rations for 45 days, and the combatants (450 Frenchmen and 350 Tonkinese) were accompanied by 1,000 Vietnamese porters, 240 French mule drivers and 200 mules. As the French were advancing through unknown country, Captain Jean-François-Alphonse Lecomte of the topographical service rode with the column to map the route. Lecomte, who served with distinction on General Louis Brière de l'Isle's staff throughout the Sino-French War, would later write a detailed account of the ambush, Le guet-apens de Bac-Lé (Paris, 1890).

The column formed at Phu Lang Thuong, the most advanced French post on the Mandarin Road, on 11 June. It set off for Lang Son on 12 June, reaching Phu Xuyen on 13 June, Kep on 14 June and Cau Son on 15 June. The march, under a sweltering summer sun, was gruelling, and on 15 June Dugenne sent Jourdy's battery back to Phu Lang Thuong. At the same time he was reinforced by a company of zéphyrs from chef de bataillon Servière's 2nd African Light Infantry Battalion.

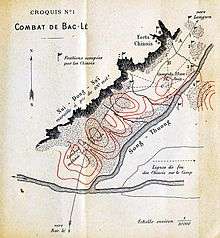

Recent heavy rain had swollen the Song Thuong river, and the French were unable to use the ford at Cau Son. The column therefore remained at Cau Son for three days while its engineers bridged the Song Thuong, and only resumed its march on 19 June. For the next three days the column pressed on to the northeast, marching parallel to the course of the Thuong river and camping in the open country between Cau Son and the small town of Bac Le. The French now became aware that their march was being observed. Single shots were heard in the distance at regular intervals, and on one occasion French cavalry scouts came under fire. It was not clear whether the attackers were Vietnamese bandits or Chinese soldiers. On the morning of 22 June the French column reached Bac Le. Continuing their march in the afternoon, the French descended once more into the Song Thuong valley and rejoined the river. Dugenne's intention was to cross the Song Thuong and continue up the Mandarin Road to Thanh Moy and Lang Son. The river was still swollen, and on the evening of 22 June Dugenne scouted its southern bank for a suitable ford. Chinese soldiers were visible on the other side of the river, and Laperrine's troopers covered them with their carbines while a French NCO tested the depth of the river. Neither side opened fire. Believing that he was dealing with stragglers from the Guangxi Army who would not oppose his passage, Dugenne gave orders for a crossing of the Song Thuong the following morning.[6]

In fact Dugenne was facing a force of 3,100 regular Chinese soldiers of the Guangxi Army under the command of Wan Zhongxuan (萬重暄). This force consisted of eight battalions under the command of Huang Yuxian (黃玉賢) and one battalion under the command of Wang Hongshun (王洪順). A further 1,500 Chinese troops under the command of Pan Dingxin (潘鼎新) were camped close by. Most of the Chinese troops were armed with modern rapid-firing Remington rifles. Both commanders were aware of the provisions of the Tientsin Accord, but as a result of the political intrigues aimed at Li Hongzhang they had received no instructions to withdraw from Tonkin. They had instead been ordered by the commander of the Guangxi Army (a yung-ying regional army), Wang Debang (王德榜), to hold their positions.[7] Wang Debang had experience serving with General Zuo Zongtang.[8][9]

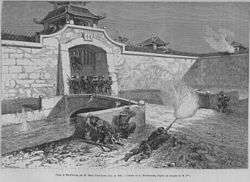

The ambush

At dawn on 23 June Captain Lecomte crossed the Song Thuong with the column's advance guard (two companies of French infantry, a section of Tonkinese riflemen and a small party of cavalry). The crossing was observed by a force of Chinese infantry deployed in a defensive position on a wooded hill 250 metres behind the river. The Chinese allowed the French troops to cross unmolested, but opened fire while the Tonkinese riflemen were crossing. Their shots were high, and it is possible that they were intended to warn rather than to kill. Lecomte reacted immediately to this hostile demonstration, deploying his infantry to flank the Chinese out of their position. The French drove the Chinese from the hill, and Lecomte established a defensive position to shelter the crossing of the rest of the column. By 11 a.m. the entire French column had crossed the Song Thuong.[10]

By then an interesting situation had developed at the French advance posts. At 9 a.m. three Chinese envoys came forward with a written message for Dugenne from the Chinese commanders. Lecomte let them through, and an interview took place. Although Dugenne's Vietnamese interpreters were unable to grasp some of the subtleties in the Chinese message, they were able to establish that the French were facing regular troops of the Guangxi Army and that the Chinese commanders were aware of their obligations under the Tientsin Accord. The Chinese generals explained that they had received no orders to withdraw, and were consequently obliged to remain in their positions until further notice. They requested Dugenne to send a heliograph message back to Hanoi to seek instructions.[11]

In view of the diplomatic significance of the confrontation, Dugenne should have reported the presence of the Chinese force to Hanoi and asked for further instructions. Instead, he informed the Chinese at 3 p.m. that he would continue his march up the Mandarin Road in one hour's time. According to Captain Lecomte (normally a reliable source), Dugenne believed that the Chinese would let him pass, and his intention was merely to get his column away from the swollen Song Thuong River and to find a secure camping ground for the night.[12]

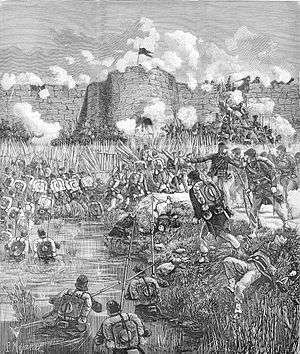

At 4 p.m. Dugenne resumed his advance. Aware of the potential for a misunderstanding, he gave strict instructions that nobody was to open fire except on his order. For several minutes the French column marched unmolested along a jungle path towards a group of Chinese forts on the cliffs of Nui Dong Nai. Seeing the path opening into a clearing, Dugenne ordered Laperrine's cavalry to replace an inexperienced section of Tonkinese riflemen at the front of the column. As the French cavalry spurred their horses forward to move to the front of the column, Chinese infantry in the Nui Dong Nai forts suddenly opened fire on them. Seconds later, Chinese infantry shadowing the march of the French column opened fire on both its flanks. It is not clear whether the Chinese were alarmed by the sudden movement of the French cavalry or (as the French believed) they mistook the horsemen for a party of senior officers and deliberately fired on this tempting target.[14]

The marine infantry of the French vanguard deployed as best they could and replied to the Chinese fire. Dugenne, who was leading the column's main body, ordered a bugler to sound for a ceasefire, but the bugle call had no effect. The Chinese were sounding their own trumpets to bring more of their own men into action, and as it became clear that the battle could not be stopped Dugenne planned his defence. He formed his men into a square, enclosing his vulnerable baggage train, and ordered them to dig trenches. During the late afternoon of 23 March the French successfully repelled repeated Chinese attacks, and were even able to counterattack with some effect. However, the Chinese brought up fresh troops during the night, and occupied positions on the heights of Nui Dong Nai from which they could fire down on the French square.[15]

On the morning of June 24, the Chinese worked their way around the sides of the French square in an attempt to cut the column's line of retreat to the Song Thuong. Dugenne made several local counterattacks to take some air around his positions, but it soon became obvious that, with no artillery support, the French would be encircled and annihilated if they remained where they were. At 11 a.m. Dugenne issued orders for a withdrawal to the Song Thuong.[16]

Although the column suffered heavy casualties from rifle fire during the withdrawal and was forced to abandon its baggage train, Dugenne successfully fought his way out of the threatened encirclement and extricated his small force. Captain Laperrine, the commander of Dugenne's small cavalry contingent, dismounted his troopers so that wounded men could be loaded onto the cavalry horses. The successful evacuation of the wounded was due in no small measure to the coolness with which Laperrine and his chasseurs d'Afrique covered the retreat.[17]

Falling back by echelons, the French recrossed the Song Thuong under fire and regrouped on its southern bank. In the afternoon of 24 June the column retreated to Bac Le, followed at a respectful distance by the victorious Chinese, and occupied a defensive position on a high plateau.[18]

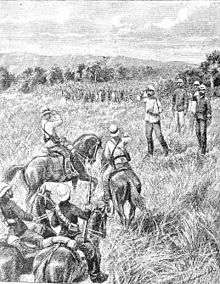

The relief expedition

Dugenne had heliographed news of the battle back to Hanoi during the night of 23 June, and General Millot, the French commander-in-chief, immediately despatched General François de Négrier and Lieutenant-Colonel Letellier to Dugenne's assistance with a substantial relief column assembled from the garrisons of Hanoi and Bac Ninh. He also ordered the 2nd Brigade of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps to concentrate at Phu Lang Thuong. De Négrier left Hanoi on 24 June with two Turco battalions, two companies of the 143rd Line Battalion and two 80-millimetre artillery batteries.[Note 2] Travelling upriver aboard a flotilla of steamboats to Phu Lang Thuong and thereafter marching light, de Négrier's relief column reached Cau Son on the evening of 25 June.[19]

De Négrier joined Dugenne's column near Bac Le on the morning of 27 June and made preparations for an immediate counterattack to throw the Chinese back across the Song Thuong. The French scouted the Chinese positions during the afternoon, and de Négrier issued orders for an attack the following morning. However, on the evening of 27 June he received a heliograph message from Millot, ordering him to return to Hanoi at once. The French premier Jules Ferry had decided to lodge a diplomatic protest and demand an explanation from the Chinese government. De Négrier complied with this unwelcome order. During the night of 28 June, under cover of a heavy thunderstorm, he and Dugenne withdrew their respective commands from the Bac Le plateau unnoticed by the Chinese. On the afternoon of 29 June the French reached Cau Son, where the wounded from the Bac Le battle were evacuated back to Phu Lang Thuong by junk. At Phu Lang Thuong the wounded were transferred to the gunboat Éclair, which ferried them rapidly back to Hanoi. In early July the exhausted men of Dugenne's column returned to Hanoi. De Négrier remained at Phu Lang Thuong with the 2nd Brigade, pressing Millot in vain for orders to attack the Chinese.[20]

Casualties

French casualties in the Bac Le Ambush were 22 dead and 70 wounded. Chinese casualties were markedly higher, approximately 300 dead and wounded in total.

Millot's order of the day

On July 1, 1884, General Millot issued the following order of the day to the men of Dugenne's column. Significantly, he blamed the engagement near Bac Le on the bad faith of the Chinese and described it as an ambush. Henceforth, the battle became, in French eyes, the 'Bac Le ambush'.

Partis en petit nombre pour occuper, conformément aux ordres du Gouvernement et suivant les conventions de Tien-Tsin, les places frontières du Tonkin et de la Chine, vous avez étés attaqués dans les gorges de Lang-Son par un ennemi déloyal qui s’était préparé pour vous attaquer dans un guet-apens. Mais grâce à votre énergie, vous avez déjoué toutes ses ruses, vous avez combattu avec succès à une contre dix et vous avez fait respecter le drapeau et l’honneur de nos armes. Quelques baggages abandonnés par les coolies sont restés au pouvoir de l’ennemi. Je le proclame bien haut : vous valez les soldats de la première République. Si vous n’avez pas vaincu, vous avez rassuré la France par votre courage, votre constance et votre héroïsme. Honneur à vous, soldats, la République vous remercie et inscrira un glorieux fait d’armes dans ses annales.[21]

(Setting out in modest force to occupy the fortresses on the frontier between Tonkin and China, in obedience to the orders of the government and in line with the provisions of the Tientsin Conventions, you were attacked in the Lang Son gorges by a treacherous enemy who set an ambush for you. Thanks to your energy you foiled all his ruses. You fought successfully at odds of one to ten and made the enemy respect our flag and the honour of our arms. Only some baggage, abandoned by the coolies, remains in his hands. I declare this firmly: you have equalled the soldiers of the First Republic. Although you have not conquered, you have reassured France with your courage, your steadfastness and your heroism. Honour to you, soldiers! The Republic sends you her thanks, and will inscribe your glorious feat of arms in her annals.)

Significance

When news of the 'Bac Le ambush' reached Paris, there was fury at what was perceived as blatant Chinese treachery. Ferry’s government demanded an apology, an indemnity, and the immediate implementation of the terms of the Tientsin Accord. The Chinese government agreed to negotiate, but refused to apologise or pay an indemnity. The mood in France was against compromise, and although negotiations continued throughout July, Admiral Amédée Courbet was ordered to take his Far East Squadron to Fuzhou (Foochow). The negotiations broke down in mid-August and on 23 August 1884, at the Battle of Fuzhou, Courbet annihilated China's Fujian Fleet, inaugurating the nine-month Sino-French War. The defeat of the French forces also resulted in the unsuccessful French attempt to attack and take Taiwan, where the Chinese Huai Army under Liu Mingchuan defeated the French at the Keelung Campaign and Battle of Tamsui.[22]

Notes

- ↑ The infantry in Dugenne’s column included the 21st, 22nd and 23rd Companies, 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Buquet, Jeannin and Penther), the 2nd Company, 2nd African Battalion (Captain Maillard), and the 12th Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain Bouchet and Lieutenants Delmotte and Bataille).

- ↑ The column included two companies of the 143rd Line Battalion (Captains Astier and Barbier) and the 11th and 12th Army Artillery Batteries (Captains Palle and de Saxcé).

Footnotes

- ↑ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

Unlike the Black Flag, the Qing troops tended to use conventional military tactics over guerilla warfare. Chinese land victories against the French were notable, albeit few in number, and the June 1884 Baclé incident is perhaps the most well known of the Chinese military victories.

- ↑ John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

In late June 1884, led by Wang Te-pang, one of Tso Tsung-t'ang's former officers, yung-ying troops participated in defeating the French near Baclé after three days of heavy fighting.

- ↑ Lloyd E. Eastman (1 January 1967). Throne and Mandarins: China's Search for a Policy During the Sino-French Controversy, 1880-1885. Harvard University Press. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-0-674-89115-9.

- ↑ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

During spring 1884, negotiations between Captain Francois Ernest Fourier and Li Hongzhang resulted in a preliminary agreement, signed on 11 May, which specified that all Chinese troops would withdraw from Tonkin and return to China, Although Li had agreed that China would retreat, the exact timetable was unclear. Thinking that the Chinese had already left Annam, a French force of 900, under Lieutenant Colonel Alphonse Dugenne, was sent to occupy Lang Son during early June 1884. Before reaching Lang Son, however, Dugenne's troops encountered a Chinese garrison near Baclé and fighting erupted.

- ↑ Lung Chang, 222–6

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 1–102

- ↑ Lung Chang, 243–5

- ↑ John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

In late June 1884, led by Wang Te-pang, one of Tso Tsung-t'ang's former officers, yung-ying troops participated in defeating the French near Baclé after three days of heavy fighting.

- ↑ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

The exact origins of the hostilities are difficult to determine. On the Chinese side, the garrison reportedly acknowledged the Li-Fourier agreement but stated that they had not yet received specific orders to leave. They therefore asked the French officers to be patient until instructions could be obtained form their superiors. As for the French, Dugenne evidently demanded immediate withdrawal according to the terms of the agreement and, when this was not forthcoming, ordered the assault on 23 June 1884. Once the fighting began, Wang Debang, a Chinese officer who received his training under Zuo Zongtang, led the Chinese troops in a three-day battle against the French forces. Although the Chinese casualties were high-approximately 300 Chinese killed to France's twenty-two dead and sixty wounded-the Chinese pushed back the French force. The Chinese portray the Baclé incident as a French defeat. Because of the ambiguity underlying the origins of the conflict, however, French accounts referred to it as a Chinese "ambush."192 Lloyd Eastman has commented on how this incident filled the French public with a "sense of righteous indignation."193

- ↑ Lecomte, Vie militaire, 47–52

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 111–19

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 119–20

- ↑ LEONORE base

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 123–6

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 131–9

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 144–9

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 149–58

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 158–65

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 175–6; Thomazi, Conquête, 196; Histoire militaire, 90

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 179–91

- ↑ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 206–7

- ↑ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

Spurred on by their defeat at Baclé, the French decided to blockade the Chinese island of Taiwan (Formosa). Beginning on 5 August 1884, Admimral Lespes bombarded Taiwan's forts at Jilong (Keelung) Harbor on the northeast coast and destroyed the gun emplacements. However, Liu Mingchuan, a former commander of the Huai Army, successfully defended Jilong against an assault by Admiral Lespes' troops the following day; the French abandoned this attack in the face of the much large Chinese forces.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sino-French War. |

- Lecomte, J., La vie militaire au Tonkin (Paris, 1893)

- Lecomte, J., Le guet-apens de Bac-Lé (Paris, 1890)

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l’Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)