Battle of Tamsui

The Battle of Tamsui, Danshui, or Hobe (2–8 October 1884) was a significant French defeat by the Qing Empire at Tamsui on Taiwan during the Keelung Campaign of the Sino-French War.

Background

The battle of Tamsui was part of the Keelung Campaign (August 1884–April 1885). Following the outbreak of the Sino-French War on 23 August 1884, the French decided to put pressure on China by landing an expeditionary corps in northern Formosa to seize Keelung and Tamsui. On 1 October Lieutenant-Colonel Bertaux-Levillain landed at Keelung with a force of 1,800 marine infantry, forcing the Chinese to withdraw to strong defensive positions which had been prepared in the surrounding hills. Meanwhile, a second French force under the command of Rear Admiral Sébastien Lespès prepared to attack Tamsui.

Liu Mingchuan took measures to reinforce Tamsui, in the river nine torpedo mines were planted and the entrance was blocked with ballast boats filled with stone which were sunk on September 3, matchlock armed "Hakka hill people" were used to reinforce the mainland Chinese battalion, and around the British Consulate and Customs House at the Red Fort hilltop, Shanghai Arsenal manufactured Krupp guns were used to form an additional battery.[2]

At Tamsui, the entrance of the river had been closed by laying down six torpedoes in the shape of a semi-circle on the inside of the bar. The Douglas steamers Fokien and Hailoong running to the port, as well as the German steamer Welle, were, whenever necessary, piloted over the torpedoes by the Chinese who had laid them down. The mandarins engaged in planting the guns that had been brought to the island by the latter steamer.Trade was resumed during the middle of the month at Twatutia, it being regarded for the time as safe, and the country thereabouts had quieted down to such an extent that a good deal of tea was brought in. Life for the foreigners was very much cramped. They were prohibited from making trips into the country; and even in the settlement, with religious processions, crackers, and, gongs going at all times of day, and the watchmen making a great noise with bamboos all night, rest was well nigh impossible except to the Chinese guards told off to protect foreign hongs, who after disappearing all day, except at meal times, "return at night, and instead of guarding the property, turn in early and sleep as soundly as Rip van Winkle did till morning."

Under the impression that the French would attempt to enter the Tamsui river, ballast boats and junks loaded with stones were sunk at the entrance. A number of Hakka hillmen were added to the government force. They were armed with their own matchlocks, which in their ignorance they preferred to foreign rifles. Much was expected of them, as the life of warfare they had led on the savage border had trained them to be good shots and handy with their knives.

By the end of August the French had succeeded in holding the shore line at Kelung, but were unable to advance beyond it; and as Chinese soldiers had for some days been erecting earthworks and digging entrenchments on the hills on the east side of the bay overlooking the shipping, the French sent word ashore for the Europeans to come on board the Bayard, as they intended opening fire on the earthworks which were now just visible.1 The firing was not successful either that day or the next, the nature of the country being in favor of the Chinese; and for many days the shelling was a regular event, the Chinese not apparently suffering much damage themselves, or being able to inflict any upon the French. This condition of affairs continued through September, the French having gained only the summits of the near hills surrounding the harbor.

General Liu Ming-chuan left Kelung on the 9th to visit Tamsui and Taipehfu. On his arrival at the latter place he was met at the wharf by some 200 soldiers, 5 buglers, and 2 or 3 drummers. The march up the street with the soldiers in front, the band next, and the general in the rear in his chair, made an imposing parade. His presence is also said to have had a most stimulating effect on the soldiers on guard in the foreign hongs. All appeared in full force with uniforms and rifles, although for several days the muster in one hong had produced only one soldier and a boy in a soldier's coat.

Liu Ming-chuan with some 6,000 men was stationed at Taipehfu in the Banka plain, while the forces at Hobe were daily strengthened, until, in the middle of October, there were assembled about 6,000 men in the neighborhood. Among these were new levies of Hakka hillmen. They were considered by the foreigners to be a dangerous lot to have in the neighborhood, and as they did not speak the same language as the general and other officers, it was feared that misunderstandings might arise with serious results. The other soldiers present were principally northern men, and were said to be well armed. The Hakkas, although armed with their primitive matchlocks, were considered to be brave men and were hardened to the privations of warfare. Their matchlocks are described as long-barrelled guns, fixed into semi-circular shaped stocks, with pans for priming powder, and armlets made of rattan, worn around the right wrist and containing pieces of bark-cord, which, when lighted, would keep alight for hours, if necessary. When in action the Hakka pours a charge of powder down the muzzle; on top of that are dropped two or three slug shot or long pieces of iron, without wadding. The trigger is made to receive the lighted piece of bark, and when powder covers the priming pan and all is ready, the trigger is pulled and if,—if the weather is dry, off goes the gun. The ordinary method of handling these weapons is to place the lower end of the butt against the right breast, high enough to enable the curved end to rest against the cheek, and the eye to look down the large barrel, upon which there are ordinarily no sights. This method is sometimes varied by discharging the guns from the hip, and it is quite customary for the Hakka to lie flat on his back, place the muzzle between his toes, and, raising his head sufficiently to sight along the barrel, to take deliberate aim and fire. He is able to make good practice; while his presence, especially when surrounded by rank grass, is decidedly difficult to determine.Rev. Dr. Mackay's Tamsui Mission Hospital, with Dr. Johansen in charge, which had rendered such great services to the Chinese wounded and had no doubt been the means of saving many lives, was visited on the 19th by General Sun, who thanked the doctor in charge as well as Dr. Browne of the Cockcliafer (who had given valuable assistance) for their attentions to the sick and wounded. The patients then numbered only a dozen, a good many of the wounded having left, fearing that the French might land again and kill them; others, seeing their wounds healing nicely, went away into the town. One man who had been shot through the left shoulder, in the region of the collar bone, after a week or ten days' treatment suddenly shouldered his rifle and left for the front, preferring life with his comrades to being confined in the hospital. It was supposed that the bullet had pierced the upper part of his lungs. Another instance occurred seven days after the French landing, when a Chinese walked into the hospital with his skull wounded and the brain visible. Several others, shot through the thighs and arms, bones being splintered in many pieces, bore their pain most heroically. Soon after the engagement, when there were seventy men in the hospital, some being badly wounded with as many as three shots apiece, there was scarcely a groan to be heard. One of the wounded came to the hospital after having had a bullet in his calf for nine or ten days. Dr. Browne extracted the bullet, and off the man went back to the front. Many other instances like the foregoing might be recorded, all of which indicated that the Chinese could recover in a few days from wounds, which, if not actually fatal, would have laid foreign soldiers up for months.

— Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present, [4]

Bombardment on 2 October

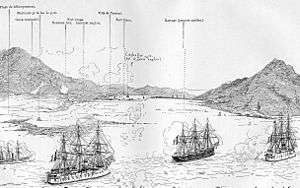

On 1 October 1884, while the Formosa expeditionary corps went ashore at Keelung, Lespès lay off Tamsui with the ironclads La Galissonnière and Triomphante, the cruiser d’Estaing and the gunboat Vipère. His orders from Courbet were to bombard the Chinese forts at Tamsui, destroy the barrage across the Tamsui River and seize Tamsui itself.

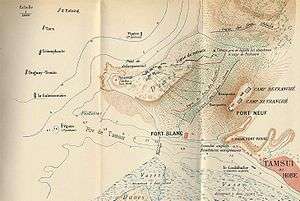

The town of Tamsui or Hobe had a population of around 6,000 at this period, including a small European colony. Tamsui was defended by two major forts, both to the west of the town. The 'White Fort',[lower-alpha 1] so called by the French to distinguish it from Fort San Domingo, the seventeenth-century Spanish 'Red Fort'[lower-alpha 3] that had become the premises of the British consulate in Tamsui, was a shore battery that commanded the entrance to the Tamsui River. To the northeast, defending the town against a landing, was a fort still under construction, the 'New Fort' (Fort Neuf). Although the New Fort was only partly armed, it had an excellent all-round field of fire. Other important fortification works had been built on all the neighbouring ridges.

The arrival of the French flotilla was the signal for feverish activity ashore, as the Chinese worked throughout the afternoon and evening to arm the New Fort and deployed their troops to repel any attempt to land by the French. The European residents of Tamsui, many of whom were British, hastily hung out Union Jacks from their houses to signal their neutrality to the French ships.[5]

As the French warships were unable to enter the Tamsui River, Lespès decided to bombard the White Fort and the New Fort on the morning of 2 October. In fact hostilities were begun by the Chinese, who began firing at sunrise on 2 October with three cannon which they had placed in the barbette of the New Fort the previous evening. The French flotilla immediately replied, delivering a heavy bombardment which lasted for several hours, eventually destroying the three Chinese guns and putting both the New Fort and the White Fort out of action.[6]

More than 2,000 shells were fired against the two forts. Many failed to explode on impact, and remained dangerous for days afterwards. Others missed their targets, because the bombardment was delivered from long range, and damaged many buildings in Tamsui itself, including all the European residences. The Canadian Presbyterian missionary George Mackay remained in his house in Tamsui during the French bombardment, refusing to take shelter aboard the British gunboat HMS Cockchafer anchored off Tamsui, because he could not take his Formosan converts with him.[7] He left a vivid description of the attack:

When the bombarding began we put our little children under the floor of the house, that they might not be alarmed. My wife went out and in during these trying hours. I paced the front of the house with A Hoa, while shot and shell whizzed and burst all around us. One shell struck a part of Oxford College, another a corner of the Girls’ School, and still another a stone in front of us, and sent it into mid-air in a thousand atoms. A little to the west of us another went into the ground, gouging a great hole and sending up a cloud of dust and stones. The suction of one, as it passed, was like a sudden gust of wind. Amid the smoke from forts and ships, and the roar and thunder of shot and shell, we walked to and fro, feeling that our God was round about us.— George Mackay, From Far Formosa, [8]

Mackay said later, in a conversation recorded by the Anglican missionary William Campbell, that the French marksmanship had been very inaccurate and had recklessly endangered the lives of innocent civilians.[9]

French preparations on 2–7 October

Realising that his naval bombardment had failed to achieve its objective and as he had only a small landing force at his disposal, Admiral Lespès sent d’Estaing back to Keelung on the evening of 2 October to request reinforcements of a battalion of marine infantry to enable him to make a landing to the north of the river, seize the forts, then destroy the command post from which the mines could be detonated. The French could then clear the pass by exploding a large powder charge, and the ships could enter the river. Meanwhile, he attempted to neutralise the mines himself. On the evening of 2 October the gunboat Vipère scouted the pass and located the buoys of the mines. On the following night the launches tried to drag the electric wires. They failed, and one of them was almost destroyed when the Chinese exploded one of the mines at a distance.[10]

D'Estaing reached Keelung on the afternoon of 3 October. By then the French had already secured the hills to the west of the town and the Chinese had retreated, but Courbet was reluctant to release one of his three battalions of marine infantry. It was probably the correct decision, though it would later be criticised. Although the Chinese had momentarily fallen back, they might launch a counterattack at any moment and, if they did, the French would need every man to hold the extensive defence perimeter they had just established at Keelung.[11]

Courbet nevertheless did what he could to give Lespès a respectable landing force. He sent him three more ships (Tarn, Châteaurenault and Duguay-Trouin), which arrived off Tamsui on the evening of 5 October. They carried their own landing companies and also the landing company from Bayard, giving Lespès a total of 600 men available for shore operations. Lespès thereupon began making preparations for a landing to assault the defences of Tamsui and clear the mines from the mouth of the Tamsui River.[12]

He organised the 600 sailors available for a landing into a battalion of five companies under the command of capitaine de frégate Martin of La Galissonnière, who had commanded the landing force at Keelung on 5 August with distinction. The ironclads Bayard, La Galissonnière and Triomphante each supplied one company. The smaller vessels d'Estaing and Châteaurenault provided a fourth company, and Tarn and Duguay-Trouin a fifth.[13]

Chinese preparations on 2–7 October

The Chinese defence was commanded by General Sun Kaihua, who had been responsible for building the New Fort in 1876. He was assisted by General Zhang Gaoyuan[lower-alpha 5] and Brigadier-General Liu Chaoyou,[lower-alpha 6] Liu Mingchuan’s great-nephew. According to Liu Mingchuan’s official report of the battle, the Chinese force included the Cho-Sheng Regiment, whose commanders included Gong Zhan'ao[lower-alpha 7] (right wing), Li Dingming[lower-alpha 8] (centre division) and Fan Huiyi[lower-alpha 9] (rear division). Two other regular battalions from different regiments were also present, under the direct command of Zhang Gaoyuan and Liu Chaoyou. A battalion of Formosan hillmen, recently enrolled by Li Tong'en,[lower-alpha 10] also fought in a skirmishing role, under the command of Tio Li-xieng.[lower-alpha 11] The Chinese force seems to have numbered around 1,000 infantry in total.[14]

General Sun deployed the Cho-Sheng Regiment in the front line. He entrenched one line of infantry in front of Fort San Domingo facing northwest, the direction from which a French assault was expected, and placed a second line of infantry in wooded terrain on the right flank, almost at a right angle to the main Chinese trenches, where it could enfilade the French advance before it reached the main defences. According to Liu Mingchuan’s report, Gong's division was posted at a spot known as 'the false creek' (Chia-chiang), and Li's division lay in ambush at Yu-ch'e-k'ou. Neither locality can now be identified. Sun commanded the regiment's defence in person.[14]

Behind Fort San Domingo, General Zhang and Brigadier-General Liu lay in reserve with two battalions of regulars, each from a different regiment, ready to counterattack when the moment was ripe. Tio Li-xieng’s hillmen were posted close to the shore in the hills to the north of the main Chinese positions, enabling them to skirmish against the left flank of the advancing French. These were intelligent dispositions, well-chosen to repulse a frontal attack.[14]

Battle on 8 October

Rough seas on 6 October and 7 October prevented a landing, but on 8 October the sea was finally calm enough for a landing to take place, and Admiral Lespès landed his 600 fusiliers-marins opposite the New Fort early in the morning. Captain Martin of La Galissonnière, the officer originally scheduled to command the attack, was ill, and command of the attack was transferred at the last moment to capitaine de frégate Boulineau of Châteaurenault. The squadron was deployed in line ahead off the harbour entrance to support the attack, facing north. The line was headed by Châteaurenault, followed by d’Estaing, Tarn, Triomphante, Duguay-Trouin and La Galissonnière, with Vipère bringing up the rear.[15]

Many of the town's European residents, excited by the prospect of a battle, formed picnic parties and flocked to vantage points on the nearby hills to obtain a good view of events. They were confident that the French would win, and expected Tamsui to be in French hands by nightfall.[16]

Boulineau deployed his five companies into two lines, with a strong guard out to the left where the danger of a flanking attack by the Chinese was strongest. His first line consisted of the landing companies of La Galissonnière and Triomphante, each of 120 men, under the respective command of lieutenants de vaisseau Fontaine and Dehorter. Dehorter’s company held the right of the line. The second line, 200 metres behind the first, consisted of the two mixed companies from the smaller ships, each of 130 men. The company from Tarn and Duguay-Trouin, under the command of enseigne de vaisseau Deman, was on the right, behind Dehorter’s company. Bayard’s landing company, 100 men strong, was posted on the left flank of the main body. The deployment, which was completed by 10 a.m. was protected by naval gunfire from the French flotilla, which swept the ground between the beach and the forts.[17]

At 10 am, Boulineau led his small force forward at a smart pace over the sand dunes. Things immediately began to go wrong. The dunes had hidden the ground beyond from the sight of the French squadron. The French had been expecting to find an open terrain of rice paddies and small clumps of trees. Instead, they discovered that the approaches to the forts were thickly wooded. The battlefield was dotted with small cultivated fields surrounded by tall hedges and spiny plants. The ground was also broken by ditches, and covered with tall bushy trees. This broken terrain provided perfect cover for the Chinese, and made control by the French commanders almost impossible.[18]

The companies and sections lost sight of one another as soon as they entered the scrub. They also began to drift off the line of advance prescribed by Admiral Lespès. Boulineau realised that there was nothing he could do to regain control, and decided he would have to rely on the initiative of his company commanders. The New Fort was still visible in the distance, so the four companies of his main body could at least see the direction in which they were supposed to be heading.[18]

Around 11:30 am, the sailors from Triomphante, on the right of the first line, made contact with Sun Kaihua's troops, concealed in the bushes and trenches between the White Fort and the New Fort. A firefight began at this point, which quickly spread along the French front line and drew in the landing company of La Galissonnière. The French front line was now under heavy fire from both the Chinese trenches to its front and from the concealed enemy positions in the woods and hedges on its left. The two reserve companies, which had fallen into disorder while picking their way across the broken ground, came up to the front line shortly afterwards. The landing company from D'Estaing and Châteaurenault entered the line between Fontaine and Dehorter's companies, while Deman's company joined the left of the line.[19]

Meanwhile, the Chinese had begun to put pressure on the French left. Despite the supporting fire provided by the French ships, Zhang Gaoyuan’s troops were able to force back the French flankguard from Bayard, pushing it back on the French main body. Bayard's sailors were able to link up with Deman's company, but the French landing force was now deployed in a single line around one and a half kilometres long. It no longer had any reserves. The firefight extended along the entire French front.[20]

The Chinese and French were separated by a distance of about 100 metres. The situation called for regular, controlled volleys by the French, but the excited sailors were firing individually into the bushes, as fast as they could. Boulineau realised that they were simply wasting their ammunition. He repeatedly yelled orders to his men to cease fire, but only a small part of his command could hear him. No bugle signals could be sent, as Boulineau's bugler had been shot dead shortly after the start of the action. The French line continued to waste its ammunition on an elusive target.[20]

The initiative now passed decisively to the Chinese. General Zhang's troops kept up their pressure on the French left, working their way around the flank of Bayard's company. General Sun's regulars also began to lap around the company from Triomphante on the French right flank, issuing out of the White Fort in large numbers. To deal with the threat to the French left, Deman took part of his company out of the front line and brought it up in support of Fontaine's men. On the right the sailors from Triomphante made a series of charges to hold back Sun's troops.

The pressure on the French line now began to tell. The French had been engaged for an hour, and had used up two-thirds of their ammunition. As the number of wounded rose, men had to be detailed to take them back to the beach. The French line also began to drift backwards. Any hope of stemming the retreat disappeared when several French officers fell in close succession. Lieutenant de vaisseau Fontaine of La Galissonnière was wounded in the foot close to the Chinese positions on the left of the French line, where the enemy fire from both front and flank was heaviest, and fell not far from the Chinese lines. Two sailors tried to bring him in, but all three men were captured by the Chinese and immediately beheaded. Enseigne de vaisseau Deman was wounded close by, and on the French right flank lieutenant de vaisseau Dehorter of Triomphante was also mortally wounded.[20]

Fontaine and Dehorter's fall was decisive. Both French flanks gave way. The landing company from Triomphante was now almost out of ammunition, and could no longer resist the pressure from Sun Kaihua's troops. On the left Bayard's company was at one point cut off from the rest of the French line by Zhang Gaoyuan's men and had to charge to disengage itself.

At midday Boulineau gave the order for retreat. The landing companies fell back to the shore, bringing their wounded and some of their dead with them. Nearly one man in every ten had been wounded, and the retreat was necessarily slow. It was covered by the landing companies of La Galissonnière and Triomphante, which fell back slowly, in good order, firing measured volleys to keep the Chinese at a distance. The French had to leave several of their dead behind during the retreat, including the bodies of Lieutenant Fontaine and his two helpers.[20]

The re-embarkation began shortly afterwards. The sea had become very rough, and the boats were unable to ground. The sailors on the beach had to wade out in water up to their necks to embark. As the sailors crowded together in the choppy water, the landing force was at the mercy of a well-timed Chinese attack. Fortunately for the French, the Chinese came up slowly and did little to hinder the evacuation. During the confusion, as the French sailors struggled to clamber aboard the boats, one of the launches capsized, tipping all its occupants into the sea. The Hotchkiss canon-revolver mounted at its bow also fell overboard. The launch was soon righted but the French had to abandon the Hotchkiss, which was later recovered by the Chinese and displayed as a trophy of victory.[21]

Lieutenant de vaisseau Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère of Vipère realised the potential danger of a Chinese counter-attack, and was given permission by Lespès to move his small gunboat to a position close inshore to cover the French withdrawal. From there it fired shells to keep the Chinese at a distance.[22]

At half past midday the first boats put out from the shore and steered towards the French ships. By 1:10 pm, they had all left the beach. Vipère followed them slowly, firing at increasingly long range at the Chinese troops on the shore. At 1.30 p.m. the boats reached the ships. The sea was now very rough, and the wounded cried out in pain as their comrades helped them up the ladders onto the ships' decks.[23]

Aftermath

The failure of the attack was an embarrassing setback to the French. Captain Garnot later blamed the defeat on the small size of the landing force, and on the use of naval landing companies rather than trained infantry:

There is no doubt that the main reason for the repulse was that the landing force was too small, but poor tactics also played their part. There was no vanguard to cover the advance of the line of battle. The firing line advanced without a preliminary reconnaissance into difficult terrain, under fire from Chinese snipers who were well dug-in and protected. Confusion and lack of direction was evident in the conduct of the battle. The courage and dash shown by our officers and sailors, who had not been trained for a land battle, cannot conceal the fact that we opened fire in a disorderly manner; that the reserves came up to join the line of battle prematurely, without orders; and that our troops lost our heads, firing wildly at the enemy and using up their ammunition in a few minutes. Infantry tactics cannot simply be improvised, as our landing companies learned by bitter experience.— Garnot, L' expédition française de Formose, [24]

The French defeat left them stuck on the northern part, unable to advance or capture more land.[lower-alpha 12]

Casualties

French casualties at Tamsui were 17 dead and 49 wounded.[lower-alpha 13] The French wounded were evacuated to Keelung aboard Tarn on 9 October and were then taken to Saigon aboard the state transport Nive. Lieutenant Dehorter, mortally wounded, was brought back to the French ships and evacuated with the other wounded. He died aboard Nive on 12 October while the transport was still at sea, and his remains were buried in Saigon.[26]

The French dead also included lieutenant de vaisseau Fontaine of La Galissonnière. The French were unable to recover Fontaine's body nor those of two French sailors killed nearby. The bodies of the three dead Frenchmen, abandoned on the battlefield, were beheaded by the Chinese, and the severed heads were paraded through Tamsui on the evening of 8 October by the victorious Chinese army. Captain Boteler of HMS Cockchafer and the British consul Frater complained strongly to Sun Kaihua about the lack of respect shown to the French dead, and the three severed heads were handed over to them for Christian burial.[27] The Chinese took prisoner and beheaded 11 French marines who were injured in addition to La Gailissonniere's captain Fontaine and used bamboo poles to display the heads in public, to incite anti-French feelings in China pictures of the decapitation of the Frenchmen were published in the Tien-shih-tsai Pictorial Journal in Shanghai.[28]

Chinese casualties, according to European employees of the Tamsui customs, were 80 dead and around 200 wounded.[29]

The New Zealand Wanganui Chronicle reported that the Chinese beheaded and killed around 20 French soldiers.[30]

Accounts of the beheadings of French troops

A most unmistakable scene in the market place occurred. Some six heads of Frenchmen, heads of the true French type were exhibited, much to the disgust of foreigners. A few visited the place where they were stuck up, and were glad to leave it—not only on account of the disgusting and barbarous character of the scene, but because the surrounding crowd showed signs of turbulence. At the camp also were eight other Frenchmen's heads, a sight which might have satisfied a savage or a Hill-man, but hardly consistent with the comparatively enlightened tastes, one would think, of Chinese soldiers even of to-day. It is not known how many of the French were killed and wounded; fourteen left their bodies on shore, and no doubt several wounded were taken back to the ships. (Chinese accounts state that twenty were killed and large numbers wounded.)In the evening Captain Boteler and Consul Frater called on General Sun, remonstrating with him on the subject of cutting heads off, and allowing them to be exhibited. Consul Frater wrote him a despatch on the subject strongly deprecating such practices, and we understand that the general promised it should not occur again, and orders were at once given to bury the heads. It is difficult for a general even situated as Sun is—having to command troops like the Hillmen, who are the veriest savages in the treatment of their enemies—to prevent such barbarities.

"It is said the Chinese buried the dead bodies of the Frenchmen after the engagement on 8th instant by order of General Sun. The Chinese are in possession of a machine gun taken or found on the beach.

— Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present[31]

ENGAGEMENT BETWEEN FRENCH AND CHINESE TROOPS AT TAMSUI. MEMORIAL FROM LIU MING-CHUAN, PUBLISHED IN MANUSCRIPT "PEKING GAZETTE" OF NOVEMBER 11th, 1884." His Majesty's Slave Liu Ming-chuan, Director of Affairs in Formosa, who holds the brevet of Provincial Governor, humbly submits the following report, showing how the enemy's troops were landed and attacked at Hobe (Tamsui), when our troops fought a sanguinary battle and gained a victory. "

The Memorialist has already reported to His Majesty the details of attack by different divisions of the French fleet upon Hobe, and of the energetic resistance that was offered by detachments of the Chinese troops selected as reinforcements for that place.

" On the 4th of October, the French fleet was reinforced by three vessels, making a total of eight in all, and these opened fire from their heavy guns against the Hobe forts, the cannonade being kept up on successive days. So unintermittent and fierce was this fire that our troops were unable to maintain their ground, and Sun K'ai-hua, Chang Kao-yuan, and Liu Chao-yuan [sic] had no resource but to conceal their troops in the woods which skirted the shore, where the men remained on the alert, passing the nights in the open air, afraid to take any rest whatsoever. At 5 a.m. on the 8th, the enemy's ships suddenly dispersed, and Sun K'ai-hua, feeling assured from certain indications that a force would be landed, directed Kung Chan-ao, the officer in charge of the right wing of the Cho Sheng regiment, to conceal himself in a place known as Chia Chang, or "dummy creek," Li Ting-ming, who commanded the central division of the same regiment, having orders to lie in ambush in a place called Yu-ch'e K'ou, while Fan Hui-yi, officer in command of the rear division, was directed to hold himself in the rear. Chang Kao-yuan and Liu Chao-yuan [sic] ensconced themselves with two battalions, each from different regiments, behind the hill at the back of the large fort in order to prevent the enemy from circumventing our forces, and a battalion of the hillmen enrolled by Li T'ung-en, under Chang Li-ch'eng, were concealed in a gully in the hill on the northern road

" These arrangements had jnst been completed when a lateral fiie was opened by the enemy's ships, which discharged no less than several hundred rounds from their heavy guns, filling the sky with smoke and flame, the shell falling round like hail. While this fire was going on, about a thousand of the enemy's troops were embarked in launches and foreign boats and landed at three points on the shore, from whence they made a straight rush for the fort, their bearing being fierce in the extreme.

" As soon as Sun K'ai-hua saw that the enemy were pressing close upon him, he stopped their advance at different points with the aid of Li Ting-ming and Fan Hui-yi, Chang Kao-yuan and others advancing fought with all their might, the struggle lasting without intermission from 7 a.m. till noon. Time after time were they driven back, but they advanced again and again. Our men engaged them fiercely at close quarters, Chang Li-ch'eng attacking them on the flank, while Sun K'ai-hua assailed them boldly in the front and killed a standard bearer, capturing the flag which he carried. The zeal of our men was increased when they witnessed the capture of the flag, aud a simultaneous rush was made from every side upon the enemy, twenty-five of whom were beheaded, amongst them being two officers, exclusive ofdd killed by musketry fire. The enemy, being unable to hold their own, finally broke and fled, our men pursuing them to the sea shore, where some seventy or more were drowned in the struggle to get to the boats. The enemy's ships while endeavoring to cover this retreat with their guns struck one of their own steam-launches, and a Gatling gun which had been left behind was captured by our men.

" The two divisions under the command of Sim K'ai-hua were the foremost to carry out his plans, and bore the brunt of the fight for a longer period than any others; they had consequently the largest number of casualties, three lieutenants being killed and over a hundred privates. All the other battalions also to the attack from the northern road. The enemy's men were armed with weapons of precision an about three hunre suffered loss.

"The above particulars of the victory were reported to the Memorialist by Sun K'ai-hua, and he would draw attention to the fierce attack made by the enemy's troops on this occasion upon the port of Hobe, when they landed their men with a fixed determination to gain the day, the intensity of their resolve to fight to the death being evidenced by the fact that their boats stood out to sea as soou as the men had been landed, in order to cut off their retreat. After the destruction of the fort our men had no guns to protect them, and had to rely solely on their own muscle in the deadly struggle that took place. Though shot and shell rained down upon them, their courage never failed them, nor did they once flinch, aud in spite of the odds agaiust them they managed to behead the standard-bearer and frustrate the fierce intentions of the foe, therein assuredly displaying energy of no ordinary kind."

The memorialist then proceeds to mention certain of the most deserving officers, naming the form of reward which he suggests should be bestowed on each. Sun K'ai-hua heads the list, his name being followed by that of the commanders of the battalions who led the van of the fight.

Commemoration

The French defeat at Tamsui on 8 October 1884 was widely publicised in China, and had a far greater effect on national morale than the simultaneous French victories in Tonkin during the Kep Campaign (6–10 October 1884). A detailed account of the battle by Liu Mingchuan, which absurdly multiplied French casualties, was published in the Peking Gazette in November 1884. In this report, Liu claimed that 300 French troops had been killed:

The French fleet being stationed off Taipei, Hobe and other places, the French troops made a vigorous attack on 8 October and landed. Sun K'ai-hua, provincial commander-in-chief, advanced by different routes to attack them with the forces under his command. Chang Kao-yuan, provincial commander-in-chief, and others also led their divisions against the enemy. The French troops were repulsed, and again advanced several times, but our troops engaged them at close quarters, Sun K'ai-hua making a direct advance upon them with his men, and beheading the officer bearing the standard, which he captured, besides killing about 300 of the enemy.— Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present[14]

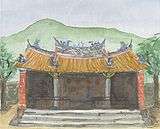

The Chinese victory is still commemorated in Tamsui. Sun Kaihua owed his victory to the intervention of the Chinese sea goddess Mazu, the deified form of the medieval Fujianese shamaness Lin Moniang, revered by the seafaring Chinese and their descendants in Taiwan. On receiving Liu Mingchuan's report of the victory, the Guangxu Emperor observed with satisfaction, "The goddess has been kind to my people and kind to myself". A wooden commemorative tablet in the Fuyou Temple,[lower-alpha 14] a Matsu temple in Tamsui completed in 1796, bears the inscription "Bright Heaven's Blessing"[lower-alpha 15] in allusion to the emperor's words.[33][34]

Significance

The battle, one of the more uncommon French defeats in the Sino-French War, was of considerable political significance. China's war party had been placed on the defensive after the loss of China's Fujian fleet in the Battle of Fuzhou on 23 August 1884, but the unexpected Chinese victory at Tamsui six weeks later bolstered the position of the hardliners in the Qing court. A court conference convened by the Empress Dowager Cixi on 28 October decided to continue the war against France until the French withdrew their demand for the payment of an indemnity for the Bac Le ambush. On 5 November the Qing court offered the French peace terms so extreme that they had no chance whatever of being accepted. They included demands for the cancellation of the Tientsin Accord, the abandonment by France of its protectorate over Annam and Tonkin, and the continuing occupation of Lao Cai, Cao Bang and Lang Son by Chinese troops. The British foreign secretary Lord Granville, who was seeking to mediate the dispute between France and China, described the Chinese terms as 'those from a victor to the vanquished' and refused to transmit them to the French. The intransigence of the Qing court ensured that the Sino-French War would continue for several more months, with increasing losses and expenditure on both sides.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Chinese: t 白砲臺, s 白炮台, p Bái Pàotái, w Pai P‘ao-t‘ai; French: Fort Blanc. The fort was also known in Chinese as Fort Zhonglun.[lower-alpha 2]

- ↑ Chinese: t 中崙砲台, s 中仑炮台, p Zhōnglún Pàotái, w Chung-lun P‘ao-t‘ai.

- ↑ French: Fort Rouge, but known in Chinese as the "Redheads' Fort".[lower-alpha 4]

- ↑ Chinese: t 紅毛城, s 红毛城, p Hóngmáo Chéng, w Hung-mao Ch‘êng.

- ↑ Chinese: 章高元, p Zhāng Gāoyuán, w Chang Kao-yuan.

- ↑ Chinese: t 劉朝祐, s 刘朝祐, p Liú Cháoyòu, w Liu Ch‘ao-yu.

- ↑ Chinese: t 龔占鼇, s 龚占鳌, p Gōng Zhàn'áo, w Kung Chan-ao.

- ↑ Chinese: 李定明, p Lǐ Dìngmíng, w Li Ting-ming.

- ↑ Chinese: 范惠意, p Fàn Huìyì, w Fan Hui-yi.

- ↑ Chinese: 李彤恩, p Lǐ Tóng'ēn, w Li T‘ung-ên.

- ↑ Chinese: t 張李成, s 张李成, p Zhāng Lǐchéng, w Chang Li-ch‘êng.

- ↑ According to Elleman: "Following this setback, the Qing court officially declared war on France on 26 August 1884. On 1 October, Admiral Courbet landed at Jilong with 2,250 men, and the city fell to the French. Chinese forces continued to encircle Jilong throughout the rest of the War. Although a French blockade thwarted all subsequent Chinese efforts to send a fleet to relieve Taiwan, the French troops never succeeded in taking the riverside town of Danshui (Tamsui) in Taiwan's northwestern coastal plain, immediately north of modern-day Taipei. As a result, French control over Taiwan was limited merely to the northern coast. China's central fleet, based in Jiangsu Province, proved unable to break through Admiral Courbet's blockade of Taiwan. Although the south quickly requested assistance from the northern fleet, Li Hongzhang refused to place his own ships in danger. This decision almost guaranteed that China's coastal waters would be dominated by the French."[25]

- ↑ The casualties among individual ships' companies were distributed as follows: La Galissonnière, 9 dead, 9 wounded; Triomphante, 4 dead, 17 wounded; Duguay-Trouin, 4 wounded; Châteaurenault, 7 wounded; Tarn, 2 dead, 4 wounded; Bayard, 3 wounded; d’Estaing, 2 dead, 5 wounded.

- ↑ Chinese: t 福佑宮, s 福佑宫, Fúyòu Gōng.

- ↑ Chinese: 翌天昭佑, yì tiān zhāo yòu.

References

Citations

- ↑ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800-1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ↑ Tsai 2009, p. 97

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 223–4

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 230–1

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 225

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 49–50

- ↑ Mackay 1896, p. 193

- ↑ Mackay 1896, pp. 193–4

- ↑ Campbell 1915, p. 156

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 50; Loir 1886, pp. 196–8

- ↑ Loir 1886, pp. 198–9

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 50–53

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 53

- 1 2 3 4 Davidson 1903, pp. 241–2

- ↑ Loir 1886, pp. 200

- ↑ Davidson 1903, pp. 225–31

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 53–4; Loir 1886, pp. 200–201

- 1 2 Garnot 1894, p. 54

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 54–5

- 1 2 3 4 Garnot 1894, p. 55

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 55–6

- ↑ Loir 1886, pp. 203

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 56

- ↑ Garnot 1894, pp. 57

- ↑ Elleman, Bruce A. (April 6, 2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 9780415214735.

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 56; Loir 1886, pp. 204–5

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 229; Garnot 1894, p. 56

- ↑ Tsai 2009, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Garnot 1894, p. 56; Lung 1993, p. 326

- ↑ "Telegraphic. Latest Cablegrams. Home and Foreign.". Wanganui Chronicle. Volume XXVIII (Issue 10653). 16 October 1884. p. 2.

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 229

- ↑ Davidson 1903, p. 241

- ↑ Crook, Steven (2014), "Fuyou Temple", Taiwan, 2nd ed., Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, pp. 32–3.

- ↑ "福佑宮", The Wonderful Color of Tamsui, Tamsui, 2002. (Chinese)

- ↑ Eastman 1967, pp. 174–83; Lung 1993, pp. 294–305

Bibliography

- Campbell, William (1915). Sketches from Formosa. London: Marshall Brothers. OL 7051071M.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan & co. OL 6931635M.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa : historical view from 1430 to 1900, history, people, resources and commercial prospects, tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants and other productions. OCLC 780197423.

- Duboc. Émile Charles Eutrope (1898). 35 mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin. Paris: Charavay, Mantoux, Martin. OCLC 9328158.

- Eastman, Lloyd E. (1967). Throne and Mandarins: China's Search for a Policy during the Sino-French Controversy, 1880-1885. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 575485068. OL 5535411M.

- Ferrero, Stéphane (2005). Formose vue par un marin français du XIXe siècle. Paris: Harmattan. ISBN 9782747594158.

- Garnot, Eugène Germain (1894). L' expédition française de Formose, 1884-1885. Paris: Librairie C. Delagrave. OCLC 3986575. OL 5225244M.

- Loir, Maurice (1886). L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet. Paris: Berger-Levrault. LCCN 03013530. OCLC 23421595.

- Lung, Chang (1993). 越南與中法戰爭 [Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (in Chinese). Taipei: 臺灣商務印書館. ISBN 9789570513141.

- Mackay, George L. (1896). From Far Formosa. New York: F. H. Revell Co. OCLC 855518794.

- Poyen-Bellisle, Isidore Henry de (1888). L'artillerie de la Marine à Formose. Paris. OCLC 752993458.

- Rollet de l'Isle, M. (1886). Au Tonkin et dans les mers de Chine. OCLC 12425765. OL 23279748M.

- Rouil, Christophe (2001). Formose: des batailles presque oubliées. Taipei. ISBN 9789578820050.

- Thomazi, Auguste (1934). La conquête de l'Indochine. Paris: Payot. OCLC 4422548. OL 6313805M.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765623287. Archived from the original on Jul 13, 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

Further reading

- Dodd, John (1888). Journal of a Blockaded Resident in North Formosa during the Franco-Chinese War, 1884-5. OCLC 464653492. OL 24154022M.

External links

- Te Aroha News - Cablegrams European

- 滬尾之戰 at the Tamsui Wiki (Chinese)

Coordinates: 25°11′N 121°25′E / 25.19°N 121.41°E