Battleships in World War II

The Second World War saw the end of the battleship as the dominant force in the world's navies. On the outbreak of the War, large fleets of battleships—many inherited from the dreadnought era decades before—were one of the decisive forces in naval thinking. By the end of the War, battleship construction was all but halted, and almost every remaining battleship was retired or scrapped within a few years of its end.

However, some farsighted commanders saw the aircraft carrier as the capital ship of the future, which was cemented by the devastating Pearl Harbor attack in 1941; the resultant Pacific War saw aircraft carriers take precedence. There were just two engagements in the Pacific Theater where battleships fought each other.[1] (There were three battleship versus battleship engagements in the Atlantic.)

Battleships remained the most heavily protected ships afloat; nonetheless, sixteen were sunk or crippled by bombs or torpedoes delivered by aircraft, while three more were sunk by submarine-launched torpedoes.[2] To make matters worse, the war had seen the development of the first guided bombs, which would make it much easier for aircraft to sink battleships in the future.

Operations

The German pre-dreadnought battleship SMS Schleswig-Holstein fired the first shots of World War II with the bombardment of the Polish garrison at Westerplatte;[3] and the final surrender of the Japanese Empire took place aboard a United States Navy battleship USS Missouri. Between the two events, it became clear that battleships were now essentially auxiliary craft, and aircraft carriers were the new principal ships of the fleet.

Still, battleships played a part in major engagements in Atlantic, Pacific and Mediterranean theatres. In the Atlantic, the Germans experimented with taking the battleship beyond conventional fleet action, using their pocket battleships as independent commerce raiders. Although there were a few battleship-on-battleship engagements, battleships had little impact on the destroyer and submarine Battle of the Atlantic, and aircraft carriers determined the outcome of most of the decisive fleet clashes of the Pacific War.

In June 1940 Scharnhorst and Gneisenau surprised and sank the lightly escorted aircraft carrier HMS Glorious off western Norway [4] This engagement marked the first and last time surface gunnery sank a fleet carrier. In the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, British capital ships opened fire on the French battleships harboured in Algeria with their own heavy guns, and later pursued fleeing French ships with planes from aircraft carriers.

Taranto and Matapan

In late 1940 and 1941, a range of engagements saw battleships harassed by carrier aircraft.

The first example of the power of naval aviation was the British air attack on the Italian naval base at Taranto that took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940. A small number of Royal Navy aircraft attacked the Italian fleet at harbour, succeeding in sinking one Italian battleship and damaging two others.

Importantly, the attack forced the Italian navy to change tactics and seek battle against the superior British navy, which resulted in their defeat at the Battle of Cape Matapan. In that battle, British carrier-deployed torpedo bombers damaged an Italian battleship sufficiently to force it to withdraw from the main force, and then at night British battleships sank the Italian force's three heavy cruisers.

Scharnhorst class

The Scharnhorst class were the first capital ships, alternatively referred to as battlecruisers or battleships, built for Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine after World War I. The class comprised two vessels: the lead ship Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Scharnhorst was launched first,[5] and so she is considered to be the lead ship by some sources; however, they are also referred to as the Gneisenau class in some other sources,[6] as Gneisenau was the first to be laid down and commissioned.[5] They marked the beginning of German naval rearmament after the Treaty of Versailles. The ships were armed with nine 28 cm (11 in) SK C/34 guns in three triple turrets, though there were plans to replace these weapons with six 38 cm (15 in) SK C/34 guns in twin turrets.

Bismarck

The battleship war in the Atlantic was driven by the attempts of German capital ship commerce raiders—two battleships, the Bismarck and the Tirpitz, and two battlecruisers—to influence the Battle of the Atlantic by destroying Atlantic convoys supplying the United Kingdom. The superior numbers of British surface units devoted themselves to protecting the convoys, and to seek-and-destroy missions against the German ships, assisted by both naval and land-based aircraft and by sabotage attacks. On 24 May 1941, during its attempt to break out into the North Atlantic, the commerce raider Bismarck engaged the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Hood. Due primarily to the Bismarck's superior range-finding and accuracy, it soon sank Hood with an apparent hit to her magazines. Bismarck and Prince of Wales hit each other three times, the damage compelling the Prince of Wales to withdraw[7] and the Bismarck to call off its commerce raiding operation, as part of its fuel reserve had been contaminated with salt water. While the Bismarck was heading for St. Nazaire, the Royal Navy continued to hunt it, and eventually an attack by Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers from the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal disabled Bismarck's rudder and significantly reduced her speed. This enabled two Royal Navy battleships, cruisers and destroyers to close in for the kill.

The Pacific battles

In many of the crucial battles of the Pacific, for instance Coral Sea and Midway, battleships were either absent or overshadowed as carriers launched wave after wave of planes into the attack at a range of hundreds of miles. The primary tasks for battleships in the Pacific became shore bombardment and anti-aircraft defense for the carriers. The two largest battleships ever constructed, Japan's Yamato class, which carried a main battery of nine 18.1-inch (460 millimetre) guns were designed to be a principal strategic weapons, but Yamato fired her main guns in only one engagement, while Mushashi never fired her main guns in an engagement. They were hampered by technical deficiencies (slow battleships were incapable of operating with fast carriers), faulty military doctrine (the Japanese waited for a "decisive battle", which never came), and defective dispositions (as at Midway).[8]

Pearl Harbor

Before hostilities broke out in the Pacific Theatre, extensive pre-war planning centered around dreadnoughts. The Royal Navy could not achieve parity with the estimated nine Japanese capital ships in Southeast Asia, since doing so would leave only a handful of ships to use against Nazi Germany. However, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was optimistic about the improving situation in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean and allocating two ships to the defense of Singapore was seen as a compromise. Furthermore, the U.S. Navy later agreed to send its Pacific Fleet with its eight powerful battleships to Singapore in the event of hostilities with Japan.[9]

On 7 December 1941 the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Five out of eight U.S. battleships were quickly either sunk or sinking, with the rest seriously damaged (of those sunk two were total losses). The Japanese thus neutralized the U.S. battleship force in the Pacific by an air attack, and thereby proved Mitchell's theory that air forces had rendered navies obsolete, and showed the vulnerability of warships lying at anchor, as at Taranto. The loss of the battleships led the US Navy to rely on aircraft carriers as capital ships to make counterattacks against the Japanese such as the Doolittle raid April 1942 and to engage Japanese naval forces at the Battle of the Coral Sea May 1942 and the Battle of Midway June 1942.

The sinking of the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and her escort, the battlecruiser HMS Repulse, further demonstrated the vulnerability of a battleship to air attack, in this case while at sea without air cover. Both ships were on their way to assist in the defense of Singapore when Japanese land-based bombers and fighters found and sank them on 10 December 1941. Prince of Wales had the unwanted distinction of being the first modern battleship sunk by aircraft while underway and able to defend herself.[10]

Midway

Commonly understood as a victory of carriers, Midway showed up deficiencies in Japanese operational planning. Yamamoto, considering his battleships the most valuable units, kept them far to the rear, in line with traditional practice. This placed them too far away to assist Nagumo (and they would have been too slow to keep up with him in any case). Yet, when Nagumo's carriers were sunk, Yamamoto lost an opportunity to salvage something. Carriers, for all their evident potency, were virtually defenseless at night, and Fletcher might have been dealt a crushing blow by Yamato the night of 6–7 June, had Yamamoto stayed closer.[11]

Guadalcanal

Initially, when the U.S. entered the war in December 1941, none of the nine Pacific Fleet battleships were available. One was being overhauled at Puget Sound Navy Yard from June 1941 until March 1942. Of the eight at Pearl Harbor, two were total losses and six had been sunk or crippled and were sent to West Coast shipyards for repair and reconstruction. With a top speed of only 21 knots, they would not have been able to keep up with the fleet carriers in any case. The new fast battleships of the North Carolina class and South Dakota class were still undergoing trials. North Carolina and South Dakota were ready by summer of 1942 and provided crucial anti-aircraft defense during the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands carrier battles.

By contrast, the Imperial Japanese Navy had the advantage of a dozen operational battleships early in the war, but chose not to deploy them in any significant engagements. The two Fusō and two Ise-class battleships, despite their extensive modernization and respectable speeds, were relegated to training and home defense, while the two Nagato and two Yamato class were being saved due to fuel limitations for a "decisive battle", which never came. In fact, the only Japanese battleships to see much action in the early stages were the four Kongō-class battlecruisers, which served mostly as carrier escorts due to their high speed and antiaircraft armament.[12]

During the later part of the Guadalcanal campaign in fall 1942, Japan and the U.S. were both forced to commit their battleships to surface combat, due to the need to carry out night operations, and because of the exhaustion of their carrier forces. During the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, battleships Hiei and Kirishima were driven off by a force of U.S. cruisers and destroyers. Several USN ships were lost and others were crippled, but they inflicted critical damage on Hiei, which was abandoned after being subject to repeated air attacks that made salvage impossible. The following evening, at the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on 15 November 1942, the United States battleships South Dakota and Washington fought and destroyed Kirishima, but only after the Japanese ship had inflicted heavy damage on South Dakota. North Carolina was also temporarily put out of action by I-19, which was credited with sinking USS O'Brien (DD-415) escorting her.

The Japanese also used battleships a single time for shore bombardment, sending Kongō and Haruna, against Henderson Field. In the most successful Japanese battleship action of the war,[13] this action killed 41 defenders and put the airfield out of action for about 12 hours.

Leyte Gulf

At the Battle of the Philippine Sea, heavy aircraft losses left the Japanese carrier fleet ineffectual and forced the Japanese to finally commit their dreadnoughts, both old and new, to the upcoming Leyte Campaign. The objective in this "decisive battle" was to stop the Allies from capturing the Philippines, which would cut off the Japanese oil supply and render their navy useless.

In the Battle of Leyte Gulf, two Japanese battleship forces converged on the American landing forces at Leyte Gulf. The Center Force of five fast battleships attacked from the north; the Southern Force of two slower old battleships attacked from the south. In the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea on 24 October 1944, the Center Force came under attack by American aircraft and Musashi, sister ship to Yamato, was sunk long before she could come within gun range of the American fleet. At the Battle of Surigao Strait early on 25 October, the Japanese Southern Force of two battleships encountered six American battleships (five of them raised and repaired from Pearl Harbor), led by Admiral Jesse Oldendorf of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, which sank Admiral Shoji Nishimura's flagship Yamashiro and would have sunk Fusō if it had not already been broken in two by destroyer torpedoes moments earlier. This engagement marked the last time in history when battleship faced battleship.

In the Battle off Samar later on 25 October 1944, the remaining four powerful battleships of the Center Force, including Yamato, Kongō, Haruna and Nagato and their cruiser escort, were defeated by the seemingly much weaker American task force of "Taffy 3" consisting of destroyers and escort carriers. American destroyers and aircraft attacked the battleships, enabling Taffy 3 to disengage and forcing the Center Force to withdraw.

Japanese Coast

During July and August 1945 several American battleships and HMS King George V conducted naval bombardments of several Japanese coastal cities. These attacks targeted major factories as well as the cities' harbors and nearby rail infrastructure.[14]

Soviet and Finnish battles

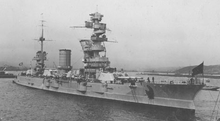

During the Soviet-Finnish Winter War, the Soviet battleships Marat and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya made several attempts to neutralize the Finnish coastal batteries to facilitate a full naval blockade. The Soviets inflicted little damage on the Finnish positions, and the defenders hit back, claiming at least one hit on Marat.[15]

During the German assault on the Soviet Union, the Soviet battleships served as convoy escorts during the evacuation of Tallinn, and as floating batteries during the siege of Leningrad.[16] The dense German and Finnish minefields and the submarine nets effectively restricted Soviet traffic in the Gulf of Finland, forcing the larger vessels to remain at port.[16][17] The German Stuka pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel eventually sank Marat at her moorings on 23 September 1941. Still, the vessel was able to serve as a battery for the remainder of the siege. The Soviets later refloated Marat and both it and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya served until the 1950s.[18]

Capabilities and tactics

Fire support

With the German capital-ship raiders sunk or forced to remain in port, shore bombardment became the focus of Allied battleships in the Atlantic. It was while covering the Allied invasion of Morocco that the USS Massachusetts fought and disabled Vichy French battleship Jean Bart on 27 October 1942. Six battleships came together as part of Operation Neptune, in support of the D-Day landings in June 1944. D-Day also saw the humble sacrifice of two old dreadnoughts (Courbet and HMS Centurion), which were scuttled as part of the breakwater around the Allied Mulberry harbours.

Aerial defense

The sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse off the coast of Malaya in 1941 demonstrated that even the most modern battleships could not hold off aerial attacks without decent aerial defenses. The British HACS fire control system had been rendered inoperable by the extreme heat and humidity of the Malaya tropical climate, and the anti-aircraft artillery had managed to shoot down only a handful of attackers.

An aircraft carrier's combat air patrol proved to be the most effective form of defense against enemy bombers. Nonetheless, a modern fast battleship could provide a vital point defense against attackers that broke through the fighter screen. The North Carolina and South Dakota demonstrated just that in the battles of the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands, respectively, with North Carolina downing between 7 and 14 planes, while South Dakota shot down between 26 and 32. The battleships' presence was crucial during these engagements in 1942, as the U.S. were still months from being able to realize their material advantage, with too few planes and ships to interdict enough of the skilled Japanese pilots. No American battleships were lost or seriously damaged by aerial attacks in open seas in World War II. By 1944, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance had arrayed his forces in a complex defense formation. The first line of protection was a radar-vectored combat air patrol, and any attackers who managed to get through would face anti-aircraft fire from a line of screening battleships and cruisers. This exacted such a heavy toll on the Japanese during the Battle of the Philippine Sea that they failed to cause any significant damage to their main targets, the aircraft carriers. The most damage that the Japanese caused was a bomb hit on South Dakota which caused many casualties but did little damage to the battleship.[19] Circumstances were vastly different from 1942 as the Japanese aircrews were inexperienced and they were up against veteran U.S. pilots. Also, the U.S. has clear numerical superiority in that battle with larger numbers of battleships and fleet carriers (with larger airwings).

AA guns

At the outbreak of World War II, most battleships had large anti-aircraft batteries. The battleships used the same light AA guns (the Allies used autocannons such as the Bofors 40 mm gun and Oerlikon 20 mm cannon) as those on smaller ships, but in greater number. The later development of proximity fuzes and radar vastly increased the effectiveness of these batteries.

_Oerlikon_20mm_AA_gun_mount.jpg)

Post–World War I battleships, particularly British and American, had discarded single purpose secondary batteries mounted in casemates used to engage surface targets in favour of turret-mounted dual purpose secondary batteries (5-inch or 6-inch caliber). Secondaries were initially designed to deal with rushing destroyers and torpedo boats, but there arose a need for heavy anti-aircraft armament as the potency of aircraft grew, particularly dive bombers and torpedo bombers. The rationale was that it is unlikely that a battleship would be simultaneously facing both destroyers and aircraft, but it would take up too much space to have separate types of guns to deal with both threats. Both weapons had similar calibers and so they could be merged into a single battery type, and the turret mountings were less susceptible to flooding and had a better firing arc than casemates. The space saved from combining the two types of guns added to simplification of supply, increased deck armor coverage, stowage of other equipment, more light anti-aircraft batteries, and other needs.

The Nelson-class battleship, incorporating many concepts from the G3 battlecruiser, was the first design to include a dual-purpose secondary battery, useful against both surface and airborne attacks. Compared to light AA they had a slower rate of fire, but they had a greater range and sufficient punch to knock enemy planes out of the sky. This proved a crucial defense against Japanese kamikazes in the latter years of World War II. They could also fire into the sea to create waterspouts that slapped low-flying torpedo bombers with tonnes of water. Battleships could mount many more of these DP batteries than cruisers or carriers.

German vessels such as the Bismarck class possessed dedicated secondary anti-ship batteries as well as dedicated heavy anti-aircraft batteries, rather than adopting the dual-purpose secondaries like the British or Americans. Bismarck for instance had a battery of twelve 5.9 inch (150 mm) cannon and another sixteen 4.1 inch (105 mm) battery was mounted to deal with air threats. The cannon could be used against ships only, as they could not be elevated to fire on high-level targets. This tended to complicate ammunition supplies, take up more space, and reduce the numbers of both guns (reducing the anti-ship or anti-aircraft broadside). The Imperial Japanese Navy suffered similar problems to the Germans', as their secondaries were too slow to track aircraft.[20]

The Japanese even used the "San Shiki" (the Beehive) Model 13 anti-aircraft shell for the main gun armament of the Yamato-class battleships, which would have in theory functioned as a super-sized "shotgun", though this was not considered a success.[21]

HMS Prince of Wales had one of the most advanced naval anti-aircraft systems of the time, the High Angle Control System, which demonstrated accurate long range radar directed AA fire during Operation Halberd in August and September 1941.[22] However the extreme heat and humidity in Malayan waters in December of that year rendered her AA FC radars unserviceable and her 2 pounder ammunition had deteriorated as well.[23] Royal Air Force technicians were called in to examine the Prince's radars but did not have sufficient time to make the repairs, rendering her HACS ineffective.[24]

Armor

In the aftermath of the Battle of Jutland and post–World War I era, designers began drawing up armor schemes that protected against ordnance dropped by aircraft or submarines. World War I ships fired at direct 90 degree trajectories. The introduction of high-angle battleship fire and plane bombings forced shipbuilders to consider adding significant armor to the top of battleships. The five ships of the American Tennessee and Colorado classes had considerably improved underwater hull protection over previous battleships, as the result of extensive experimentation and testing. The new class of Battleship was to include 40" of armored plating. The proposed G3 battlecruiser was planned to incorporate a thoroughly tested torpedo defense scheme, which was later used in the Nelson class. Not surprisingly, as many World War I battleships lacked such a protection system, they fared poorly against torpedoes, which in World War II were increasingly being delivered by submarines and aircraft.

Battleships had an armored belt along the waterline. It was intended to stop shells that hit their sides and to prevent flooding by underwater explosions due to near misses. World War I battleship, German and Italian World War II battleships had lighter upper armored belts to protect sides up to the main or weather deck. Main belt thickness along the waterline ranged from 10" to 15", upper belt thickness ranged from 4" to 10". Most ships of the World War II period had a sloped main belt (internal in some classes), to increase resistance to incoming shells; and no upper belt, to save weight. Thicknesses of belt armor ranged from 10" for Strasbourg class - large battlecruisers rather than pure battleships - or from 12" South Dakota and Iowa classes) to 16" (Yamato class).[25][26]

World War I ships had a light upper armored deck to protect the secondary guns and a main armored deck whose sides sloped down to meet the lower edge of the belt, but their thickness was usually no more than 1.5", or 2" for the slopes. As soon as long-range engagements became common and aerial threats increased, crash programs to improve deck and turret roof protection started. US Navy "all-or-nothing" armor layout introduced a flat heavy armor deck, which abutted the upper edges of the armored belt, and light armored weather and lower decks: this design was used by all World War II ships except Reichsmarine units, that kept a heavier lower deck and a lighter upper deck. Main deck armor thickness ranged from 4" to 6" or even 9" for Yamato class, usually increased over magazines: lighter decks were 1.5" to 2" thick.[26]

From the lessons of Jutland, the protection scheme incorporated a sophisticated torpedo defense system (TDS).[27] By adopting a turbo-electric drive, this allowed a wholesale rearrangement and close subdivision of the machinery spaces, while simultaneously narrowing them and permitting more space outboard for a layered system of voids, liquid-filled tanks and thin armored bulkheads.[28] By contrast, "thin-skinned" cruisers and carriers relied only on numerous compartments to prevent flooding from spreading. Some were upgraded with anti-torpedo blisters, though these were much inferior to the battleship's armored belt. During the Pearl Harbor attack, TDS and damage control counterflooding saved West Virginia from nine torpedo hits, while Oklahoma, which lacked it, capsized after just three.

For the Attack on Pearl Harbor the JNAF adapted 16" shells from Nagato-class battleships into an aerial bomb specifically designed to penetrate the deck armor of the American battleships. It was one of these weapons, dropped from a Nakajima B5N level bomber, which resulted in the destruction of the USS Arizona.[29][30]

During the attack on Yamato, according to a PBS documentary, U.S. torpedo bombers were taught to aim for either the bow or the stern, where the protective belt did not extend. For torpedo bombers to make their runs successfully, fighters strafed the battleship to suppress AA guns, and dive bombers wreaked havoc on the upper decks, destroying AA weapons and fire control systems. Pilots were also instructed to focus on one side of the ship, causing massive flooding which was difficult to counteract, leading to the ship capsizing. A bow hit was deadly, since the onrushing water from the battleship's high speed could wrench the hole open wider and collapse compartment bulkheads, which was why Yamato's sister, Musashi, foundered at Sibuyan Sea.[31] The stern attacks are best demonstrated by the cases of Bismarck and Prince of Wales; the rudders and screws were similarly vulnerable.

Fleet Air Arm planned to release their armor-piercing bombs from above a certain height so they would penetrate Tirpitz's thick armor during Operation Tungsten.[32] As the British pilots did not release their ordnance from the optimal altitude, Tirpitz suffered extensive damage to her upperworks but her deck armor remained intact.[33] While the suicide air attacks—the so-called kamikaze—struck many U.S. battleships, none were seriously damaged due to their thick armor. Kamikaze were much more successful against lesser-armored ships.[34]

There were limits to the battleship's protection scheme, since it could not keep pace with the faster pace of developments in ordnance. For instance, the TDS in the South Dakota and Iowa-class battleships were designed to absorb the energy from an underwater explosion equivalent to 700 pounds (317 kg) of TNT — the Navy's best guess in the 1930s about Japanese weapons. But unbeknownst to U.S. Naval Intelligence, the Japanese 24-inch (60 cm) Type 93 torpedo, carried a charge equivalent to 891 pounds (405 kg) of TNT. And no amount of armor that could be practically incorporated would have saved the Tirpitz from the massive 12,000 lb (5.4t) Tallboys dropped by RAF Lancaster bombers during Operation Catechism.[35][36] Notably a Tallboy bomb that hit Tirpitz amidships between the aircraft catapult and the funnel blew a massive hole into the ship's side and bottom, destroying the entire section of belt armour abreast of the bomb hit, which caused significant flooding and contributed to the ship's rapid list and eventual capsizing.[37]

Coordination and waves

In a well-planned attack, fighter planes strafed the battleship to suppress the AA guns, while dive bombers used their armor-piercing bombs to cause topside damage and havoc. The fighters and dive bombers, however, were diversions to allow the delivery of aerial torpedoes.

Battleships were able to sustain more punishment and had fewer vulnerable spots than cruisers and carriers, so it was difficult to rely upon scoring a critical hit (the cases of the Bismarck and Prince of Wales are considered exceptional). Instead, the way to defeat battleships was by attrition, by overwhelming them with repeated waves of attacks inflicting accumulating damage. This is best demonstrated at the Battle of Leyte Gulf; at the Sibuyan Sea where the super-dreadnought Musashi eventually succumbed to her damage, after being beset by waves of U.S. carrier aircraft and with her being the primary focus of their attacks. The U.S. planes would have accomplished less if they spread out to attack the rest of the ships in Kurita's powerful force. By contrast, the 24 October air attack on Nishimura's southern pincer did little damage, even though both of his Fusō-class battleships were slow World War I-era dreadnoughts and his force had far fewer screening ships, as he only faced a single wave from U.S. carriers Franklin and Enterprise.

Innovative Attacks

The Axis Powers implemented some unconventional methods. The Italians used with success their tested method of having frogmen delivering explosive charges to the ships, managing to severely damage HMS Queen Elizabeth and to a lesser extent HMS Valiant in the shallow waters of the harbor of Alexandria, putting Valiant out of action until mid-1942 and Queen Elizabeth until mid-1943. Other more or less successful Italian methods included manned torpedoes and small motor assault boats, which were filled with explosives, aimed at the target, sped up to full speed, while the pilot catapulted himself out from the dashing craft.[38]

The Germans developed a series of stand-off weapons, e.g., the guided bomb Fritz X, which scored some early successes. On 9 September 1943, the Germans managed to sink the Italian battleship Roma and severely damage her sister ship, the Italia, while they were underway to surrender. The first one hit Roma amidship between 90 mm AA gun mounts, piercing deck and side, then exploded, halving her speed; the other one hit above deck between turret #2 and the conning tower. It caused an explosion that threw the turret overboard and affected the boilers, starting a major fire that detonated the main magazines. 1,353 lives were lost; only 596 survivors, most badly burned, were rescued. Among those killed was the Italian Commander in Chief of Naval Battle Forces, Admiral Carlo Bergamini. One week later, the Germans scored another hit on the British battleship HMS Warspite. The bomb penetrated six decks before exploding against the bottom of the ship, blowing a large hole in her. The ship took in a total of 5,000 tonnes of water, lost steam (and thus all power, both to the ship herself and to all her systems), and had to be taken in tow. She reached Malta but was out of action for the next 12 months.[39]

The British further developed their ability to sink battleships in harbour with minisubs and very heavy bombs dropped by strategic bombers. The last active German battleship, Tirpitz, lurked until late into the war in Norwegian fjords protected by anti-submarine weapons and shore based anti-aircraft guns. She was severely damaged in September 1943 during Operation Source, a daring covert attack by British mini-subs. After several air strikes, including Operation Tungsten, which was made with carrier aircraft, Tirpitz was finally sunk in harbour by RAF heavy bombers carrying massive tallboy bombs. During that action, codenamed Operation Catechism, two of the bombs penetrated her armor, one holing her portside and the other starting a fire that eventually detonated her magazines and blew off her Caesar turret, causing her to capsize and killing 1,000 of the 1,700 men aboard.[23][36]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Pearl Harbor attack was a radical development of Japanese strategy that only occurred in 1941. It is also likely the American plan for the Pacific involved a prompt battleship engagement. Evans and Peattie, p.471-7

- ↑ The battleships Conte di Cavour, Arizona, Utah, Oklahoma, Prince of Wales, Roma, Musashi, Tirpitz, Yamato, Schleswig-Holstein, Impero, Lemnos, Kilkis, Marat, Ise and Hyūga were all put out of commission or destroyed by aerial attack including bombs, air-dropped torpedoes and missiles fired from aircraft.

- ↑ Gibbons, p. 163

- ↑ Gibbons, pp. 246–247

- 1 2 Gröner, p. 32.

- ↑ Collier, p. 99.

- ↑ Gibbons, pp. 228–229

- ↑ Willmott, H.P. Barrier and the Javelin (Annapolis: USNIPress, 1983).

- ↑ The sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse (Forcez-survivors.org)

- ↑ Axell, Albert: Kamikaze, p. 14

- ↑ Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin, passim.

- ↑ Gibbons, pp. 262–263

- ↑ Stille, Cdr Mark (2008). Imperial Japanese Navy Battleships 1941–1945. p 19, Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-280-6

- ↑ Morison (1960), pp. 312–316, 331–332

- ↑ Appel, Erik: Finland i krig 1939–1940, p. 182

- 1 2 Linder, Jan: Ofredens hav, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Brunila, Kai: Finland i krig 1940–1944, pp. 100–108, 220–225

- ↑ Greger, René: Schlachtschiffe der Welt, pp. 201

- ↑ Battle of the Philippine Sea (CombinedFleet.com)

- ↑ Japanese Naval Ordnance (CombinedFleet.com)

- ↑ "Jap Yamoto bat" (txt). Ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ↑ The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean Convoys. A Naval Staff History, p26

- 1 2 Battleship: The Loss of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, Middlebrook

- ↑ Alan Matthews, 2006, "The sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse" (Force Z Survivors Association). Access date: 13 October 2007.

- ↑ Gardner 1980, pp.98-99

- 1 2 Gardner 1980, p.178

- ↑ Best Battleship: Underwater Protection (CombinedFleet.com)

- ↑ A Survey of the American "Standard Type" Battleship (navweaps.com)

- ↑ Note: This weapon was called 800 kg armor-piercing bomb Type 99, No 80, Mark 5. The development of this bomb is described in At Dawn We Slept.

- ↑ Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn We Slept: The untold story of Pearl Harbor. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1981. ISBN 0-07-050669-8 p.161.

- ↑ The Loss of Battleship KONGO: As told in Chapter "November Woes" of "Total Eclipse: The Last Battles of the IJN - Leyte to Kure 1944 to 1945". (CombinedFleet.com)

- ↑ Best Battleship: Armor (CombinedFleet.com)

- ↑ Tirpitz: The History (www.bismarck-class.dk/tirpitz/history/tiropertungsten.html)

- ↑ Axell, Albert: Kamikaze, pp. 205–213

- ↑ Tamelander, Michael: Slagskeppet Tirpitz

- 1 2 Jacobsen, Alf R.: Dödligt angrepp

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin, p. 273.

- ↑ Taylor, A. J. P.: 1900-talet, p. 139

- ↑ Ireland, Bernard: Jane's War at Sea, pp. 190–191

References

- Appel, Erik; et al. (2001). Finland i krig 1939–1940 - första delen (in Swedish). Espoo, Finland: Schildts förlag Ab. p. 261. ISBN 951-50-1182-5.

- Archibald, E. H. H. (1984). The Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1897–1984. Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-1348-8.

- Axell, Albert; et al. (2004). Kamikaze - Japans självmordspiloter (in Swedish). Lund, Sweden: Historiska media. p. 316. ISBN 91-85057-09-6.

- Brown, D. K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. Book Sales. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Brown, D. K. (2003). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Caxton Editions. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-84067-531-3.

- Brunila, Kai; et al. (2000). Finland i krig 1940–1944 - andra delen (in Swedish). Espoo, Finland: Schildts förlag Ab. p. 285. ISBN 951-50-1140-X.

- Burr, Lawrence (2006). British Battlecruisers 1914–18. New Vanguard No. 126. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-008-0.

- Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) and Gray, Randal (Author) (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Naval Institute Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) (1980). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Gardiner, Robert (Ed.) and Lambert, Andrew (Ed.). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The steam warship 1815–1905 - Conway's History of the Ship. Book Sales. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7858-1413-9.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers - A Technical Directory of all the World's Capital Ships from 1860 to the Present Day. London, UK: Salamander Books Ltd. p. 272. ISBN 0-517-37810-8.

- Greger, René (1993). Schlachtschiffe der Welt (in German). Stuttgart, Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. p. 260. ISBN 3-613-01459-9.

- Ireland, Bernard and Grove, Eric (1997). Jane's War At Sea 1897–1997. London: Harper Collins Publishers. p. 256. ISBN 0-00-472065-2.

- Jacobsen, Alf R. (2005). Dödligt angrepp - miniubåtsräden mot slagskeppet Tirpitz (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Natur & Kultur. p. 282. ISBN 91-27-09897-4.

- Kennedy, Paul M. (1983). The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery. London. ISBN 0-333-35094-4.

- Lambert, Andrew (1984). Battleships in Transition - The Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815–1860. London: Conway Maritime Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-85177-315-X.

- Lenton, H. T. (1971). Krigsfartyg efter 1860 (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Forum AB. p. 160.

- Linder, Jan; et al. (2002). Ofredens hav - Östersjön 1939–1992 (in Swedish). Avesta, Sweden: Svenska Tryckericentralen AB. p. 224. ISBN 91-631-2035-6.

- Massie, Robert (2005). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-411-3.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1960). Victory in the Pacific. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Volume Fourteen. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07065-8.

- O'Connell, Robert L. (1991). Sacred Vessels: the Cult of the Battleship and the Rise of the U.S. Navy. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1116-0.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships. first published Seeley Service & Co, 1957, published United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Anthony (Foreword) (1989). Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. London, UK: Random House Ltd. p. 320. ISBN 1-85170-494-9.

- Russel, Scott J. (1861). The Fleet of the Future. London.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare 1815–1914. London. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

- Stilwell, Paul (2001). Battleships. New Your, USA: MetroBooks. p. 160. ISBN 1-58663-044-X.

- Tamelander, Michael; et al. (2006). Slagskeppet Tirpitz - kampen om Norra Ishavet (in Swedish). Norstedts Förlag. p. 363. ISBN 91-1-301554-0.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (Red.); et al. (1975). 1900-talet: Vår tids historia i ord och bild; Part 12 (in Swedish). Helsingborg: Bokfrämjandet. p. 159.

- Wetterholm, Claes-Göran (2002). Dödens hav - Östersjön 1945 (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Bokförlaget Prisma. p. 279. ISBN 91-518-3968-7.

- Wilson, H. W. (1898). Ironclads in Action - Vol 1. London.

- Zetterling, Niklas; et al. (2004). Bismarck - Kampen om Atlanten (in Swedish). Stockholm, Sweden: Nordstedts förlag. p. 312. ISBN 91-1-301288-6.

- Corbett, Sir Julian. "Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905." (1994). Originally Classified and in two volumes. ISBN 1-55750-129-7.