Belisarius

| Flavius Belisarius | |

|---|---|

Belisarius may be this bearded figure [1] on the right of Emperor Justinian I in the mosaic in the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, which celebrates the reconquest of Italy by the Byzantine army. Compare Lillington-Martin (2009) page 16 | |

| Native name | Βελισάριος |

| Born |

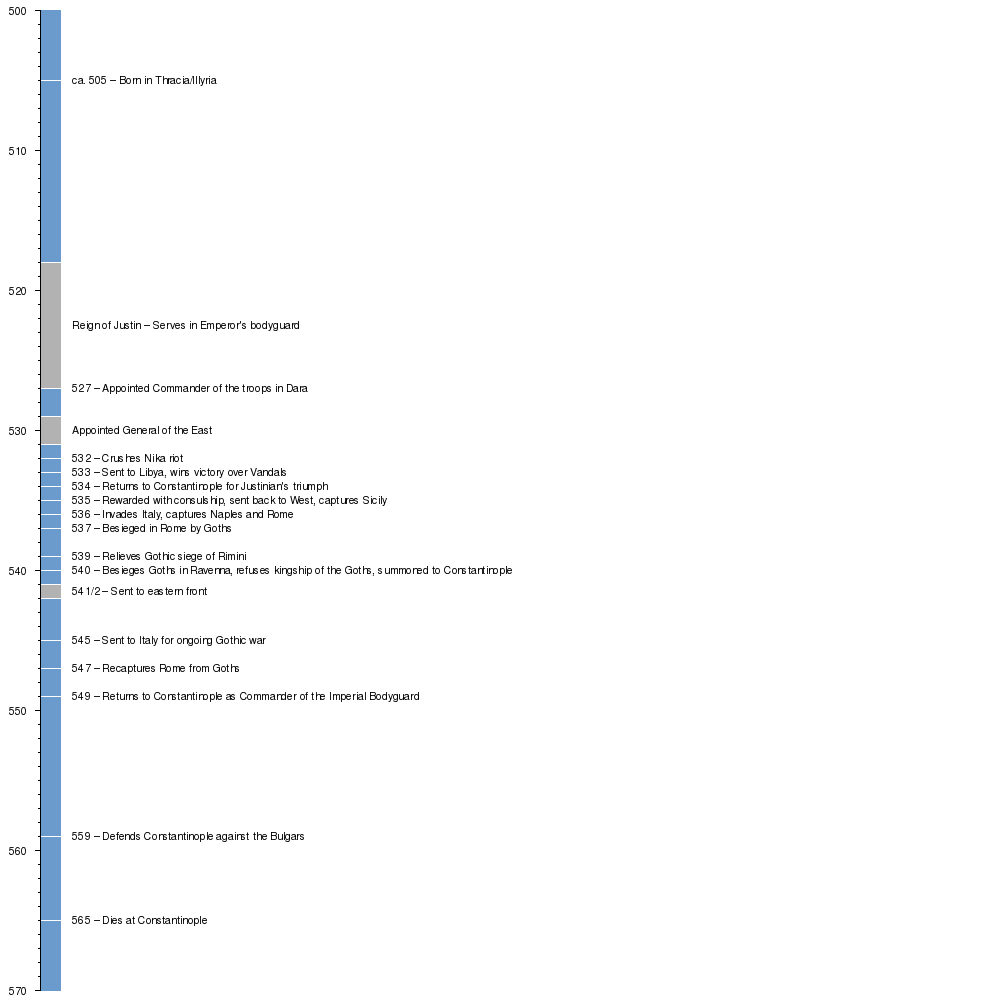

c. 505 Germane, modern-day Sapareva Banya |

| Died |

c. March 565 (age 59/60) Rufinianae, Chalcedon |

| Buried at | Saints Peter and Paul |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Byzantine army |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held | Roman army in the east, land and sea expedition against the Vandal Kingdom, Roman army |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Dara, Battle of Callinicum |

| Spouse(s) | Antonina |

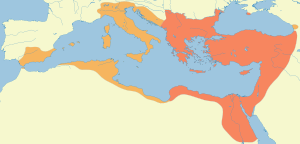

Flavius Belisarius (Greek: Βελισάριος, c. 505[2] – 565) was a general of the Byzantine Empire. He was instrumental to Emperor Justinian's ambitious project of reconquering much of the Mediterranean territory of the former Western Roman Empire, which had been lost less than a century previously.

One of the defining features of Belisarius' career was his success despite varying levels of support from Justinian. His name is frequently given as one of the so-called "Last of the Romans".

Early life and career

Belisarius was probably born in Germane or Germania, a fortified town (some archaeological remains exist) on the site of present-day Sapareva Banya in south-west Bulgaria, in the borders of Thrace and Paeonia or in Germen a town in Thrace near Adrianople, nowadays in Greece.[3] Born into an Illyrian[4][5][6][7][8] or Thracian[9] family of possible Gothic ancestry,[10] he spoke Latin as a mother tongue and became a Roman soldier as a young man, serving as bodyguard of Emperor Justin I.[4][11]

He came to the attention of Justin and his nephew, Justinian, as a promising and innovative officer. He was given permission by the emperor to form a bodyguard regiment (bucellarii), of heavy cavalry, which he later expanded into a personal household regiment, 1,500 strong. Belisarius' bucellarii were the nucleus around which all the armies he would later command were organized. Armed with a lance, (possibly Hunnish style) composite bow, and broadsword, they were fully armoured to the standard of heavy cavalry of the day. A multi-purpose unit, they were capable of skirmishing at a distance with bow, like the Huns; or could act as heavy shock cavalry, charging an enemy with lance and sword. In essence, they combined the best and most dangerous aspects of both of Rome's greatest enemies, the Huns and the Goths.

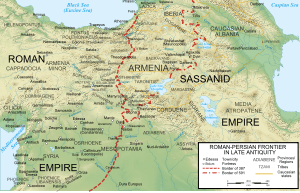

Following Justin's death in 527, the new emperor, Justinian I, appointed Belisarius to command the Roman army in the east to deal with incursions from the Sassanid Empire. He quickly proved himself an able and effective commander, defeating the larger Sassanid army through superior generalship. In June/July 530, during the Iberian War, he led the Romans to a stunning victory over the Sassanids in the Battle of Dara, followed by a tactical defeat at the Battle of Callinicum on the Euphrates in 531—this was perhaps a strategic victory in that the Persians retreated to their own borders. This led to the negotiation of an "Eternal Peace" with the Persians, and Roman payment of heavy tributes for years in exchange for peace with Persia. This freed resources for redeployment elsewhere.

In 532, he was the highest-ranking military officer in the Imperial capital of Constantinople when the Nika riots broke out in the city (among factions of chariot racing fans) and nearly resulted in the overthrow of Justinian. Belisarius, with the help of the magister militum of the Illyricum, Mundus, along with Narses and John the Armenian, suppressed the rebellion with a bloodbath in the Hippodrome, the gathering place of the rebels, that is said to have claimed the lives of 30,000 people.

Military campaigns

Against the Vandals

For his efforts, Belisarius was rewarded by Justinian with the command of a land and sea expedition against the Vandal Kingdom, mounted in 533–534. The Romans had political, religious, and strategic reasons for such a campaign. The pro-Roman Vandal king Hilderic had been deposed and murdered by the usurper Gelimer, giving Justinian a legal pretext. Furthermore, the Arian Vandals had periodically persecuted the Nicene Christians within their kingdom, many of whom made their way to Constantinople seeking redress. The Vandals had launched many pirate raids on Roman trade interests, hurting commerce in the western areas of the Empire. Justinian also wanted control of the Vandal territory in north Africa, which was one of the wealthiest provinces and the breadbasket of the Western Roman Empire and was now vital for guaranteeing Roman access to the western Mediterranean.

In the late summer of 533, Belisarius sailed to Africa and landed near Caput Vada (near Chebba on the coast of Tunisia). He ordered his fleet not to lose sight of the army, then marched along the coastal highway toward the Vandal capital of Carthage. He did this to prevent supplies from being cut off, and to avoid a great defeat such as occurred during Basiliscus' first attempt to retake northern Africa 65 years before, which had ended in the Roman disaster at the Battle of Cap Bon in 468.

Ten miles from Carthage, the forces of Gelimer (who had just executed Hilderic) and Belisarius finally met at the Battle of Ad Decimum on September 13, 533. It nearly turned into a defeat for the Romans. Gelimer had chosen his position well and had some success along the main road. The Romans, however, seemed dominant on both sides of the main road to Carthage. At the height of the battle, Gelimer became distraught upon learning of the death of his brother in battle. This gave Belisarius a chance to regroup, and he went on to win the battle and capture Carthage. A second victory at the Battle of Tricamarum on December 15 of the same year resulted in Gelimer's surrender early in 534 at Mount Papua, restoring the lost Roman provinces of north Africa to the empire. For this achievement, Belisarius was granted a Roman triumph (the last ever given) when he returned to Constantinople. According to Procopius in the procession were paraded the spoils of the Temple of Jerusalem (the Vandal treasure, including many objects looted from Rome 80 years earlier, the imperial regalia and the menorah of the Second Temple among them) which had been recovered from the Vandal capital along with Gelimer himself before he was sent into peaceful exile. Medals were stamped in his honor with the inscription Gloria Romanorum, though none seem to have survived to modern times. Belisarius was also made sole Consul in 535, being one of the last persons ever to hold this office, which originated in the ancient Roman Republic.

Nevertheless, the recovery of Africa was not complete; army mutinies and revolts by the native Berbers would plague the new praetorian prefecture of Africa for almost 15 years.

Against the Ostrogoths

Justinian now resolved to restore as much of the Western Roman Empire as he could. In 535, he commissioned Belisarius to attack the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy. Belisarius landed in Sicily and took the island for use as a base against Italy, while Mundus recovered Dalmatia. The preparations for the invasion of the Italian mainland were interrupted in Easter 536, when Belisarius sailed to Africa to counter an uprising of the local army. His reputation made the rebels abandon the siege of Carthage, and Belisarius pursued and defeated them at Membresa. Thereupon he returned to Sicily, and then crossed into mainland Italy, where he captured Naples in November and Rome in December 536.

In 537–538 he successfully defended Rome against the Goths and moved north to take the Ostrogoth capital of Ravenna in 540, where the Goth king Witiges was captured. Shortly before the taking of Ravenna, the Ostrogoths had offered to make Belisarius the western emperor. Belisarius feigned acceptance and entered Ravenna via its sole point of entry, a causeway through the marshes, accompanied by a comitatus of bucellarii, his personal household regiment. Soon afterwards, he proclaimed the capture of Ravenna in the name of the Emperor Justinian.

The Goths' offer raised suspicions in Justinian's mind and Belisarius was recalled. He returned home with the Gothic treasure, king and warriors.

Belisarius was recalled in part to deal with the Persian conquest of Syria, a crucial province of the empire, where he successfully fended off renewed attacks. He defeated the Persian army under Nabades at Nisibis, but couldn't take the city because it was fortified and well defended by the Persians. He captured Sisauranon, a small Persian fort to the east. Here Belisarius sent Harith with 1200 Roman troops under John the Glutton and Trajan to plunder Assyria. The expedition was successful, penetrating far into enemy territory and gathering much plunder. In the campaign of 542, Belisarius' presence just to the west of the Euphrates effectively prevented Khusro from advancing further, and the king decided to retreat. Belisarius was nonetheless acclaimed throughout the East for his success in repelling the Persians.[12]

Belisarius returned to Italy in 544, where he found that the situation had changed greatly. In 541 the Ostrogoths had elected Totila as their new leader and had mounted a vigorous campaign against the Romans, recapturing all of northern Italy and even driving the Romans out of Rome. Belisarius managed to recover Rome briefly but his Italian campaign proved unsuccessful, due in no small part to his limited supplies and reinforcements, perhaps as Justinian's empire had suffered from the plague of 541–542. In 548/9, Justinian relieved him. In 551, after economic recovery (from the effects of the plague) the eunuch Narses led a large army to bring the campaign to a successful conclusion. For his part, Belisarius retired from military affairs. At the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople (553), Belisarius was one of the Emperor's envoys to Pope Vigilius in their tug of war over The Three Chapters. The Patriarch Eutychius, who presided over this council in place of Pope Vigilius, was the son of one of Belisarius' generals.

Deposition of Pope Silverius

During the Siege of Rome an incident occurred for which the general would be long condemned: Belisarius, a Byzantine Rite Christian, was commanded by the monophysite Christian Empress Theodora to depose the reigning Pope, who had been installed by the Goths. This Pope was the former subdeacon Silverius, the son of Pope Hormisdas. Belisarius was to replace him with the Deacon Vigilius, Apocrisarius of Pope John II in Constantinople. Vigilius had in fact been chosen in 531 by Pope Boniface II to be his successor, but this choice was strongly criticised by the Roman clergy and Boniface eventually reversed his decision.

In 537, at the height of the siege, Silverius was accused of conspiring with the Gothic King and several Roman senators to secretly open the gates of the city. Belisarius had him stripped of his vestments and exiled to Patara in Lycia in Asia Minor. Following the advocacy of his innocence by the bishop of Patara he was ordered to return to Italy at the command of the Emperor Justinian and, if cleared by investigation, reinstated. However, Vigilius had already been installed in his place and Silverius was intercepted before he could reach Rome and exiled once more, this time on the island of Palmarola (Ponza), where by one account he is said to have starved to death, others say he left for Constantinople. However that may be, he remains the patron saint of Ponza today.

Belisarius, for his part, built a small oratory on the site of the present church of Santa Maria in Trivio in Rome as a sign of his repentance. He also built two hospices for pilgrims and a monastery, which have since disappeared. Santa Maria in Trivio is around the corner from the Trevi fountain; a 12th-century inscription is the only surviving monument of the great general.

Later life and campaigns

The retirement of Belisarius came to an end in 559, when an army of Kutrigur Bulgars under Khan Zabergan crossed the Danube River to invade Roman territory for the first time and threatened Constantinople itself. Justinian recalled Belisarius to command the Roman army. In his last campaign, Belisarius defeated the Kutrigurs and drove them back across the river with the greatly outnumbered force under his command.

In 562, Belisarius stood trial in Constantinople on a charge of corruption. The charge is presumed to be trumped-up, and modern research suggests that his former secretary Procopius of Caesarea may have judged his case. Belisarius was found guilty and imprisoned. However, not long after, Justinian pardoned him, ordered his release, and restored him to favour at the imperial court.

In the first five chapters of his Secret History, Procopius characterises Belisarius as a cuckold husband, who was emotionally dependent on his debauched wife, Antonina. According to the historian, Antonina cheated on Belisarius with their adopted son, the young Theodosius. Procopius claims that the love affair was well known in the imperial court and the general was regarded as weak and ridiculous; this view is often considered biased, as Procopius nursed a longstanding hatred of both Belisarius and Antonina. Empress Theodora reportedly helped and saved Antonina when Belisarius tried to charge his wife at last.

Fittingly, Belisarius and Justinian, whose partnership increased the size of the empire by 45%, died within a few months of each other in 565. Belisarius owned the estate of Rufinianae on the Asiatic side of the Constantinople suburbs. He may have died there and been buried near one of the two churches in the area, perhaps Saints Peter and Paul.

Timeline

Legend as a blind beggar

According to a story that gained popularity during the Middle Ages, Justinian is said to have ordered Belisarius' eyes to be put out, and reduced him to the status of homeless beggar near the Pincian Gate of Rome, condemned to asking passers-by to "give an obolus to Belisarius" (date obolum Belisario), before pardoning him. Most modern scholars believe the story to be apocryphal, though Philip Stanhope, a 19th-century British philologist who wrote Life of Belisarius—the only exhaustive biography of the great general—believed the story to be true. Based on a parsing of the available primary sources, Stanhope created an argument for the legend's authenticity.

Though the legend remains of dubious provenance, after the publication of Jean-François Marmontel's novel Bélisaire (1767), this account became a popular subject for progressive painters and their patrons in the later 18th century, who saw parallels between the actions of Justinian and the repression imposed by contemporary rulers. For such subtexts, Marmontel's novel received a public censure by Louis Legrand of the Sorbonne, which contemporary divines regarded as model expositions of theological knowledge and clear thinking (Catholic Encyclopedia: "Louis Legrand"). Marmontel and the painters and sculptors (a bust of Belisarius by the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Stouf is at the J. Paul Getty Museum) depicted Belisarius as a kind of secular saint, sharing the suffering of the downtrodden poor. The most famous of these paintings, by Jacques-Louis David, combines the themes of charity (the alms giver), injustice (Belisarius), and the radical reversal of power (the soldier who recognises his old commander). Others portray him being helped by the poor after his rejection by the powerful.

In art and popular culture

Belisarius was featured in several works of art before the 20th century. The oldest of them is the historical treatise by his secretary, Procopius. The Anecdota, commonly referred to as the Arcana Historia or Secret History, is an extended attack on Belisarius and Antonina, and on Justinian and Theodora, indicting Belisarius as a love-blind fool and his wife as unfaithful and duplicitous. Other works include:

Belisarius as a character

Drama

- Belasarius: a play by Jakob Bidermann (1607)

- The life and history of Belisarius, who conquer'd Africa and Italy, with an account of his disgrace, the ingratitude of the Romans, and a parallel between him and a modern hero: a drama by John Oldmixon (1713)

- Belasarius: a drama by William Philips (1724)

Literature

- Bélisaire: a novel by Jean-François Marmontel (1767)

- Belisarius: A Tragedy: by Margaretta Faugères (1795). Though she wrote it as a play, Faugères "intended [this work] for the closet," i.e., to be read and not performed. Her preface voices complaints about "maledictions" and long-winded rhetoric in popular tragic drama, which she says tend to bore and even outrage a reader, and announces her intent to "substitute concise narrative and plain sense." The drama's plot and character development are secondary to moral conflicts, mainly between vengeance and mercy/pity, respectively associated with pride and humility.

- Beliar: 18th-century poem by Friedrich de la Motte Fouque.

- Ein Kampf um Rom: an historical novel by Felix Dahn (1867)

- Belisarius, 19th-century poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

- Count Belisarius: a novel by Robert Graves (1938); Ostensibly written from the viewpoint of the eunuch Eugenius, servant to Belisarius' wife, but actually based on Procopius's history, the book portrays Belisarius as a solitary honorable man in a corrupt world, and paints a vivid picture of not only his startling military feats but also the colorful characters and events of his day, such as the savage Hippodrome politics of the Constantinople chariot races, which regularly escalated to open street battles between fans of opposing factions, and the intrigues of the emperor Justinian and the empress Theodora.

- Lest Darkness Fall: an alternative history novel by L. Sprague de Camp (1939). Belisarius appears first as the Roman opponent of the time traveler Martin Padway who tries to spread modern science and inventions in Gothic Italy. Eventually Belisarius becomes a general in Padway's army and secures Italy for him.

- The character "Bel Riose" in Foundation and Empire by Isaac Asimov is based on Belisarius (1952)

- A Flame in Byzantium: an historical horror fiction novel by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (1987)

- The Belisarius series: six science fiction novels by Eric Flint and David Drake. Alternate history exploring what might have happened if Belisarius and a rival were granted knowledge of future events and technologies. The first four books are available as free ebooks from the Baen Free Library, or all six at The Fifth Imperium website.[13]

- Belisarius: The First Shall Be Last (2006) and Belisarius: Glory of the Romans (2010): novels by Paolo Belzoni[14]

Opera

- Belisario: tragedia lirica by Gaetano Donizetti, libretto by Salvatore Cammarano after Luigi Marchionni's adaptation of Eduard von Schenl's Belisarius (1820), scenography by Francesco Bagnara, premiered during the Stagione di Carnevale, 4 February 1836, Venezia, Teatro La Fenice.

Comics

- Destiny: A Chronicle of Deaths Foretold: comic book miniseries authored by Alisa Kwitney with art by Kent Williams, Michael Zulli, Scott Hampton, and Rebecca Guay (1997). Belisarius briefly appears as a jealous husband, imprisoning his wife in their quarters due to rumors of her affairs, instead of fighting in Italy.

Games

- Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings: A video game by Ensemble Studios (1999). Belisarius is a "Hero" that can only be accessed in the map editor. He has the appearance of a Cataphract, the Byzantine unique unit.

- Civilization IV: A video game by Take Two (2005). Belisarius is a "Great Person"; specifically, one of many Great Generals that arise through gameplay via successful warfare with other civilizations but not barbarians.

- Civilization V: Belisarius, like in Civilization IV, appears as a "Great General".

- Total War: Attila: The player can command the army of Belisarius at the Battle of Ad Decimum. He is also featured as the main protagonist in "The Last Roman" Campaign Pack where you can take the role of Belisarius, tasked with reclaiming the former territory of the Western Empire.

- He is in a tutorial level of Empire Earth.

Films

- Belisarius was portrayed by Lang Jeffries in the 1968 German movie Kampf um Rom I, directed by Robert Siodmak.

References and mentions

Literature

- Mardi: novel by Herman Melville (1849); Melville playfully assigns the moniker "my Belisarius" to the Samoan Islander first encountered aboard the abandoned vessel "Parki".

- Jorge Luis Borges mentioned the legend of Belisario as a blind beggar in some of his poetic works, for example, "A quien ya no es joven," the first verse of which reads: "Ya puedes ver el tragico escenario y cada cosa en lugar debido; la espada y la ceniza para Dido y la moneda para Belisario."[15]

- Foundation and Empire: a science fiction novel by Isaac Asimov, second novel in the Foundation Series (1952). The character Bel Riose, based on Belisarius, is the last great general of the first Galactic Empire, which was modelled on the late Roman Empire.

- The General: a series of military science fiction novels by S. M. Stirling and David Drake. The plot draws much from the life and campaigns of Belisarius; the main character, Raj Whitehall, sets out to reunite the planet of Bellevue after the fall of galactic civilization.

- The Sarantine Mosaic: a pair of alternate historical fantasy novels by Guy Gavriel Kay which follows the mosaicist Crispin and his entanglement in the affairs of the court under Emperor Valerius II and his general Leontes, loosely based on Justinian and Belisarius in the time immediately before and leading up to the attempt to reclaim the lost Western empire.

- Buffy The Vampire Slayer: Immortal Belasarius was turned into a Vampire by Veronqiue back in that time period. No one knew and thus he remained General while serving Veronique.

- The Belisarius Series is a fictional saga in the alternate history and military history subgenres of science fiction, written by American authors David Drake and Eric Flint.

Games

- Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb: a video game by LucasArts (2003). During his quest to find the tomb of the first emperor of China, Indiana Jones learns that the Nazis have discovered Belisarius' "sunken temple" beneath a mosque in Constantinople.

- The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion: a video game by Bethesda Softworks (2006). A soldier named Belisarius is found in the Cloud Ruler Temple as a non-player character and another character with the name Belisarius is a speaker of the Black Hand only seen in the final Dark Brotherhood quest Honor thy Mother.

- Freespace 2: A video game by Volition Inc. The ship NTCv Belisarius is destroyed after emerging from subspace, heavily damaged and defiant of all calls to surrender, despite facing a superior enemy.

- "Belisarius' War" game by Decision Games.

Television

- Belisarius is the namesake of Donald Bellisario's production company, Belisarius Productions.

See also

-

Byzantine Empire portal

Byzantine Empire portal

Notes

- ↑ Mass, Michael (June 2013). "Las guerras de Justiniano en Occidente y la idea de restauración". Desperta Ferro (in Spanish). 18: 6–10. ISSN 2171-9276.

- ↑ The exact date of his birth is unknown. PLRE III, p. 182

- ↑ Robert Graves, Count Belisarius and Procopius’s Wars, 1938

- 1 2 Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A history of the Byzantine state and society. Stanford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the later Roman Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-299-03944-8. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ↑ History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the death of Justinian volume 2, by J.B.Bury p.56

- ↑ The Age of Faith: The Story of Civilization by Will Durant, Chapter V

- ↑ Count Marcellinus and His Chronicle by Brian Croke, p.75

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). Battles that changed history : an encyclopedia of world conflict (1st ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0.

- ↑ Frassento, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 1-57607-263-0. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ Evans, James Allan (2003-10-01). The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian. University of Texas Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-292-70270-7. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 363-628 by Geoffrey Greatrex,Samuel N. C. Lieu, p. 108-110

- ↑ http://baencd.thefifthimperium.com/15-WhentheTideRisesCD/

- ↑ http://www.arxpub.com/literary/Belisarius.html

- ↑ El Otro, El Mismo (1964) in Jorge Luis Borges, Obra Poética p.218

References

Primary sources

- Procopius, Belisarius and Narses, Academic Fellowship, 1964.

- Procopius, The Secret History of the Court of Justinian, online at Gutenberg Project.

Secondary sources

- "Belisarius" Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 27 Apr 2009

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Belisarius". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Belisarius". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- R. Boss, R. Chapman, P. Garriock, Justinian's War: Belisarius, Narses and the Reconquest of the West, Montvert Publications, 1993, ISBN 1-874101-01-9.

- Henning Börm, Justinians Triumph und Belisars Erniedrigung. Überlegungen zum Verhältnis zwischen Kaiser und Militär im späten Römischen Reich. In: Chiron 43 (2013), pages 63–91.

- Glanville Downey, Belisarius: Young general of Byzantium, Dutton, 1960

- Edward Gibbon has much to say on Belisarius in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 41 online.

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher 2006–2013:

- 2006, "Pilot Field-Walking Survey near Ambar & Dara, SE Turkey", British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara:Travel Grant Report, Bulletin of British Byzantine Studies, 32 (2006), pages 40–45;

- 2007, "Archaeological and Ancient Literary Evidence for a Battle near Dara Gap, Turkey, AD 530: Topography, Texts and Trenches" in: BAR –S1717, 2007 The Late Roman Army in the Near East from Diocletian to the Arab Conquest Proceedings of a colloquium held at Potenza, Acerenza and Matera, Italy edited by Ariel S. Lewin and Pietrina Pellegrini, p 299–311;

- 2008, "Roman tactics defeat Persian pride" in Ancient Warfare edited by Jasper Oorthuys, Vol. II, Issue 1 (February 2008), pages 36–40;

- 2009, "Procopius, Belisarius and the Goths" in: Journal of the Oxford University History Society,(2009) Odd Alliances edited by Heather Ellis and Graciela Iglesias Rogers. ISSN 1742-917X, pages 1– 17, https://sites.google.com/site/jouhsinfo/issue7specialissueforinternetexplorer;

- 2010, "Source for a handbook:Reflections of the Wars in the Strategikon and archaeology" in: Ancient Warfare edited by Jasper Oorthuys, Vol. IV, Issue 3 (June 2010), pages 33–37;

- 2011, "Secret Histories", http://classicsconfidential.co.uk/2011/11/19/secret-histories/;

- 2012, "Hard and Soft Power on the Eastern Frontier: a Roman Fortlet between Dara and Nisibis, Mesopotamia,Turkey, Prokopios' Mindouos?" in: The Byzantinist, edited by Douglas Whalin, Issue 2 (2012), pages 4–5, http://oxfordbyzantinesociety.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/obsnews2012final.pdf;

- 2013a, "La defensa de Roma por Belisario" in: Justiniano I el Grande (Desperta Ferro) edited by Alberto Pérez Rubio, 18 (July 2013), pages 40–45, ISSN 2171-9276;

- 2013b, "Procopius on the struggle for Dara and Rome" in: War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives (Late Antique Archaeology 8.1–8.2 2010–11) by Sarantis A. and Christie N. (2010–11) edd. (Brill, Leiden 2013), pages 599–630, ISBN 978-90-04-25257-8.

- Martindale, John R.; Jones, A. H. M.; Morris, J. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. IIIa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 181–224. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- Lord Mahon, The Life of Belisarius, 1848. Reprinted 2006 (unabridged with editorial comments) Evolution Publishing, ISBN 1-889758-67-1

- Lord Mahon, The Life of Belisarius, J. Murray, 1829. With a new critical introduction and further reading by Jon Coulston. Westholme Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-59416-019-8

- Ancient Warfare magazine, Vol. IV, Issue 3 (Jun/Jul, 2010), was devoted to "Justinian's fireman: Belisarius and the Byzantine empire", with articles by Sidney Dean, Duncan B. Campbell, Ian Hughes, Ross Cowan, Raffaele D'Amato, and Christopher Lillington-Martin.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belisarius. |

| Preceded by Imp. Caesar Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus Augustus IV, Flavius Decius Paulinus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 535 |

Vacant Title next held by John the Cappadocian |