Bennington College

|

College logo | |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Established | 1932 |

| Endowment | US $ 18.5 million[1] |

| President | Mariko Silver |

| Provost | Isabel Roche |

Academic staff | 117 |

| Students | 755 |

| Undergraduates | 660 |

| Location | Bennington, Vermont, United States |

| Campus | Rural, 440 acres (1.8 km2) |

| Mascot | No official mascot |

| Website | www.bennington.edu/ |

Bennington College is a private, nonsectarian liberal arts college located in Bennington, Vermont, USA. The college was founded in 1932 as a women's college and became co-educational in 1969. It is accredited with the New England Association of Schools & Colleges (NEASC).

History

1920s

The planning for the establishment of Bennington College began in 1924 and took nine years to be realized. While many people were involved, the four central figures in the founding of Bennington were Vincent Ravi Booth, Mr. and Mrs. Hall Park McCullough, and William Heard Kilpatrick.[2]

A Women's Committee, headed by Mrs. Hall Park McCullough, organized the Colony Club Meeting in 1924, which brought together some 500 civic leaders and educators from across the country. As a result of the Colony Club Meeting, a charter was secured and a board of trustees formed for Bennington College. One of the trustees, John Dewey, helped shape many of the College's signature programs such as The Plan Process and Field Work Term through his educational principles.[2]

In 1928, six years before the College would begin, Robert Devore Leigh was recruited by the Bennington College executive committee to serve as the first president of Bennington. Leigh presided over the forging of Bennington's structure and its early operation. In 1929 Leigh authored the Bennington College Prospectus which outlined the "Bennington idea."[2]

1930s

The first class of eighty-seven women arrived on campus in 1932. The College was the first to include the visual and performing arts as full-fledged elements of the liberal arts curriculum. Every year since the College began in 1932, every Bennington College student has engaged in internships and volunteer opportunities each winter term. Originally called the Winter Field & Reading Period, the two-month term was described by President Robert Devore Leigh in his 1928 Bennington College Prospectus as "a long winter recess giving students and faculty opportunity for travel, field work, and educational advantages of metropolitan life." This internship was renamed twice, as Non-Resident term and, as it is called today, Field Work Term.[2]

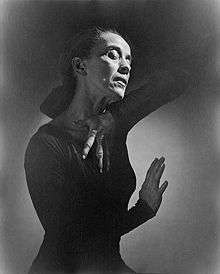

In 1934 the Bennington School of Dance summer program was founded by Martha Hill. Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Hanya Holm, and Charles Weidman all taught at this laboratory. The program gained attendance by José Limón, Bessie Schonberg, Merce Cunningham, and Betty Ford. In 1935 the administration agreed to admit young men into the Bennington Theater Studio program, since men were needed for theatrical performances. Among the men who attended was the actor Alan Arkin.[2]

1940s–1980s

In 1951 the U.S. State Department issued a documentary on Bennington highlighting its unique educational approach as a model for the Allied rebuilding of German society after the War.[3]

Built in 1959, the Edward Clark Crossett Library was designed by the award-winning modernist architect Pietro Belluchi. After opening, Crossett Library was featured in Architectural Forum and became a focus of study for many architecture students in the 1960s. Crossett Library went on to win the 1963 Honor Award for library design. In 1968, three new student houses were completed to help house the growing student population and were named in honor of William C. Fels, Jessie Smith Noyes, and Margaret Smith Sawtell. These houses were designed by the distinguished modernist architect Edward Larrabee Barnes who posthumously earned the 2007 American Institute of Architects Gold Medal. In 1969 Bennington became fully co-educational, a move that attracted major national attention, including a major feature story in the New York Times Magazine.

1990s

In 1993, the Bennington College Board of Trustees initiated a process known as "The Symposium." Arguing that the college suffered from "a growing attachment to the status quo that, if unattended, is lethal to Bennington's purpose and pedagogy,"[4] the Board of Trustees "solicit[ed]...concerns and proposals on a wide and open-ended range of issues from every member of the faculty, every student, every staff member, every alumna and alumnus, and dozens of friends of the College."[5] According to the Trustees, the process was intended to reinvent the college, and the Board said it received over 600 contributions to this end.[5]

The results of the process were published in June 1994 in a 36-page document titled Symposium Report of the Bennington College Board of Trustees. Recommended changes included the following:

- Adoption of a "teacher-practitioner" ideal;[6]

- Abandonment of academic divisions in favor of "polymorphous, dynamically changing Faculty Program Groups";[7]

- Replacement of the college's system of presumptive tenure with "an experimental contract system";[8] and

- A 10% tuition reduction over the following five years.[9]

Near the end of June 1994, 27 faculty members (approximately one-third of the total faculty body) were notified by certified mail that their contracts would not be renewed.[10] (The exact number of fired faculty members is listed as 25 or 26 in some reports, a discrepancy partly because at least one faculty member, photographer Neil Rappaport, was reinstated on appeal shortly after his firing.)[11] As recommended in the Symposium, the Trustees abolished the presumptive tenure system, leaving the institution with no form of tenure. The firings attracted considerable media attention.

Some students and alumni protested, and the college was censured for its actions by the American Association of University Professors, who said, "...academic freedom is insecure, and academic tenure is nonexistent today at Bennington College."[12] Critics of the Symposium, and the 1994 firings, have alleged that the Symposium was essentially a sham, designed to provide a pretext for the removal of faculty members to whom the college's president, Elizabeth Coleman, was hostile.[13] Some have questioned the timing of the firings, arguing that by waiting until the end of June, the college made it impossible for students affected by the firings to transfer to other institutions.[14]

President Coleman responded that the decision was fundamentally "about ideas", stating that "Bennington became mediocre over time" and that the college was in need of radical change.[13] Coleman argued that the college was in dire financial straits, saying that "had Bennington done nothing...the future of this institution was seriously in doubt."[15] In a letter to the New York Times, John Barr, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, asserted that Coleman was "not responsible for the redesign of the college...It was the board of trustees".[16]

In May 1996, seventeen of the faculty members terminated in the 1994 firings filed a lawsuit against Bennington College, seeking $3.7 million in damages and reinstatement to their former positions.[17] In December 2000, the case was settled out of court; as part of the settlement, the fired faculty members received $1.89 million and an apology from the college.[18] In the immediate wake of the controversy, for the 1994–1995 academic year, the college's enrollment dropped to a record low of 370 undergraduates,[19] and the following year (1995–1996), undergraduate enrollment declined to 285.[20][21] According to Coleman, a student body of 600 undergraduates was required for the college to break even.[19]

2000s and beyond

In recent years, Bennington's reputation and enrollment have accelerated upward and the school has received recognition for many of the unique advantages it offers students. As of 2015, the college reports a healthy total enrollment of 755 students with steady increases in quality student applications.[22] Bennington was also selected by The Princeton Review as one of the top colleges in America, and doing so not by conforming to the norms but rather by reaffirming its unique approach to education. Bennington remains true to its ideals, in combining practical and material in classroom deliverables and through internships, focusing on interdisciplinary academics rather than the more typical channeled approach to majors and departments, and through a continued emphasis on the combination of liberal arts, sciences, and fine arts together - in staunch defiance of the norm where the latter is often an afterthought. Bennington College appeared in Princeton's 2017 Best Northeastern Colleges List, which includes the schools that it considers "...academically outstanding and well worth consideration in your college search." Bennington also appeared on Princeton's "Green Schools" list.[23] Notably, Bennington was also featured in an article by Forbes as one of "Tomorrow's Hot Colleges" highlighting the institution's recent flourishing "...under bold, entrepreneurial leadership." [24]

Bennington continues to be spotlighted amongst the top 10 Colleges and Universities in the country earning recognition for:

- Number 2 for "Best Classroom Experience" —Princeton Review;

- Number 2 for "Most Beautiful Campus" —Princeton Review;

- Number 3 for "Professors Get High Marks" —Princeton Review;

- Number 5 for "Best College Theater" —Princeton Review;

- Number 6 for "Best College Dorms" —Princeton Review;

- Number 8 for "Most Politically Active Students" —Princeton Review;

- Number 4 for "America's Most Entrepreneurial Colleges" —Forbes; and

- "Top Ten Brainiest Colleges" —Unigo; Colleges Where Students Get Internships —US News & World Report

In 2015 Bennington College announced a $5 million endowment bequest from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. The largest single gift ever awarded by the foundation has helped establish the Helen Frankenthaler Fund for the Visual Arts and provides support for all aspects of the school's visual arts program including curricula, facilities, programs, and faculty. In recognition of the gift, the visual arts wing of the college's 120,000-square-foot arts facility was renamed the Helen Frankenthaler Visual Arts Center.

College presidents

| Term | Name |

|---|---|

| 1928–1941 | Robert Devore Leigh |

| 1941–1947 | Lewis Webster Jones |

| 1947–1957 | Frederick H. Burkhardt |

| 1957–1964 | William C. Fels |

| 1965–1971 | Edward J. Bloustein |

| 1972–1976 | Gail Thain Parker |

| 1977–1982 | Joseph Murphy |

| 1982–1986 | Michael K. Hooker |

| 1987–2013 | Elizabeth Coleman |

| 2013–current | Mariko Silver |

Academics

- The student to faculty ratio is 8:1 and the average class size is 13 students.[26]

Admissions

- 63.5% acceptance rate[27]

- Average GPA of 3.5 for accepted freshmen[28]

- Test scores, such as SAT and ACT, are optional. Nevertheless, the students who plan to submit standardized tests scores have a SAT score of 1840-2070 and ACT score of 27-32 [29]

Financial aid

- 2015–2016 charges is $65,590(including indirect costs). The total is broken down into $47,590 for tuition, $14,200 for room & board,& $3,800 for books,supplies, personal expenses etc.[30]

- 90% of undergraduates receive financial aid [27]

- Financial aid is awarded for 99.8% of those undergraduates found to have financial need

- 80% of undergraduate need is met[31][32]

Special programs

- Center for Creative Teaching[33]

- Isabelle Kaplan Center for Languages and Culture[34]

- Quantum Leap Program

Graduate programs

Master's degrees offered: MFA in Writing, MA in Teaching a Second Language, MFA in Performing Arts, and Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program.[35]

Graduate program in writing

Bennington College has a low-residency Master of Fine Arts program in writing. The Atlantic recently named it one of the nation's best, and Poets & Writers Magazine named it one of the top three low-residency programs in the world.[36] Core faculty has included fiction writers David Gates, Amy Hempel, Jill McCorkle, and Lynne Sharon Schwartz; nonfiction writers Sven Birkerts, Susan Cheever, Phillip Lopate, Tom Bissell, and George Scialabba; and poets April Bernard, Major Jackson, Timothy Liu, Amy Gerstler, Mark Wunderlich, and Ed Ochester. The Writing Seminars were founded by the poet Liam Rector. Following Rector's death in August 2007, Sven Birkerts took over as acting director of the Writing Seminars. He was subsequently named director in January 2008, following a nationwide search for Rector's successor.

Postbaccalaureate premedical program

For students who have excelled in an undergraduate program in an area other than science and now wish to acquire the prerequisites necessary to apply to medical and other health-related professional schools, Bennington offers a one-year intensive science curriculum.

The program offers advising and support through and beyond the postbac year during the medical school admissions process. Postbac students are both recent college graduates and experienced professionals from many backgrounds advancing on to Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, UVM, Yale and other prestigious medical and health profession schools.[37]

Campus

The groundbreaking ceremony for Bennington College took place on August 16, 1931 and construction of the original Bennington College campus was completed by 1936. The Boston architectural firm, J.W. Ames and E.S. Dodge designed Commons, the 12 original student houses, as well as the reconfiguration of the Barn from a working farm building into classrooms and administrative offices. The original student houses were named for the people integral to the founding of the College. The campus was built by more than 100 local craftsmen, many of whom had been out of work since the stock market crash of 1929.[2] The campus stretches 440 acres with main campus centered on 10 acres. There are 300 wooded acres, 15 acres of wetland, and 5 acres of tilled farmland.

Academic buildings

- The Barn

- Center for the Advancement of Public Action

- Crossett Library

- Dickinson Science Building

- Jennings Music Building

- Deane Carriage Barn

- Stickney Observatory

- Tishman Lecture Hall

- East Academic Center Buildings

- Visual and Performing Arts Center

Residence halls

94% of students live on campus. There are 21 student houses and all dorms are co-educational. Each dorm hosts a weekly "Coffee Hour" on Sunday evenings where students discuss campus and house issues together. There are also 15 staff/faculty houses.[38][39]

Colonial houses

|

|

Barnes houses

|

Woo houses

|

Other houses

- Longmeadow

- Welling Town House

- Shingle Cottage

Dining, fitness, and recreation

- Historic Commons Building

- Meyer Recreation Barn & Climbing Gym

- The Student Center & Snack Bar

- The Upstairs/Downstairs Cafe

- Soccer Field

- Tennis Courts

- Basketball Court

- Running and Hiking Trails

Student life

Bennington College has a total undergraduate enrollment of 668, with a gender distribution of 32.9 percent male students and 67.1 percent female students. 94.0 percent of the students live in college-owned, -operated, or -affiliated housing and 6.0 percent of students live off campus.[40]

Annual events[41]

- 24-Hour Play

- Plays are written and performed in the span of one day.

- Pigstock

- Springtime party featuring live music and a pig roast.

- Roll-a-rama

- Roller skating in Greenwall Auditorium.

- Sunfest

- A day-long music festival in May.

Student publications

The Silo is a student-run and produced journal of arts and letters at Bennington College. It has been published since 1943.[42]

The Bennington Free Press is the student-run and produced newspaper of Bennington College. It has been published since 2003.[43]

"Footnotes" is an academic journal created by the Student Educational Policies Committee, beginning in Spring 2016

Notable alumni and faculty

Better known Bennington alumni include actors such as Alan Arkin, Anne Ramsey, Carol Channing, Justin Theroux, Tim Daly, Molly Tarlov, Holland Taylor, and Peter Dinklage; writers such as Donna Tartt, Kiran Desai, Bret Easton Ellis, Jonathan Lethem; musicians such as Anthony Wilson and the members of the band Mountain Man; artists such as Susan Crile, Helen Frankenthaler, Cora Cohen, and Liz Phillips; academics such as Judith Butler and Michael Pollan; activist Andrea Dworkin and screenwriter Melissa Rosenberg. Kiran Desai ('93) won the Man Booker Prize (UK) (2006) for her novel The Inheritance of Loss[44] and Donna Tartt won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014 for her novel The Goldfinch. Alan Arkin ('55) won an Academy Award in 2007 for his role in Little Miss Sunshine.[45]

Faculty has included Wharton and James biographer R. W. B. Lewis, essayist Edward Hoagland, literary critic Camille Paglia, rhetorician Kenneth Burke, former United Artists' senior vice-president Steven Bach, novelists Arturo Vivante, Bernard Malamud and John Gardner, trumpeter/composer Bill Dixon, composers Allen Shawn, Henry Brant, and Vivian Fine, painters Kenneth Noland and Jules Olitski, politicians Mansour Farhang and Mac Maharaj, poets Léonie Adams and Howard Nemerov, sculptor Anthony Caro, dancer/choreographer Martha Graham, drummer Milford Graves, author William Butler (author of The Butterfly Revolution), economist Karl Polanyi and a number of Pulitzer Prize-winning poets including W. H. Auden, Stanley Kunitz, Mary Oliver, Theodore Roethke and Anne Waldman.

See also

References

- ↑ , US News & World Report America's Best Colleges, rankingsandreviews.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bennington College Timeline". Bennington College. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Bennington College Propaganda Film (1951)". youtube.com. 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ↑ Bennington College Board of Trustees (1994), Symposium Report of the Bennington College Board of Trustees (PDF), p. 7, retrieved 2007-07-07

- 1 2 Symposium Report, p. 8.

- ↑ Symposium Report, p. 11.

- ↑ Symposium Report, p. 14.

- ↑ Symposium Report, p. 17.

- ↑ Symposium Report, p. 22.

- ↑ Edmundson, Mark (October 23, 1994), "Bennington means business", New York Times: 1 [Section 6, Col. 1]

- ↑ Dembner, Alice (April 15, 1995), "National professors' group calls Bennington overhaul a 'purge'", Boston Globe: 22 [Metro–Region section]

- ↑ Howie, Stephen S. (May 5, 2002), "Bennington makes recovery its own way: President is credited with setting the course", Boston Globe: B11 [Education section]

- 1 2 Edmundson, "Bennington means business".

- ↑ December, Alice (September 14, 1994), "Striking a discord: Record low enrollment follows radical changes at Bennington College", Boston Globe: 1 [Metro–Region section]

- ↑ "Change begins at Bennington", St. Louis Post-Dispatch: 12C, June 28, 1994

- ↑ "Bennington means business (letter response)", New York Times: 22 [Section 6, Col. 4], November 27, 1994

- ↑ Yemma, John (May 8, 1996), "Laid-off Bennington faculty members sue", Boston Globe: 32

- ↑ "17 Dismissed Professors Win Suit at Bennington", New York Times: 16 [Section A, Column 1], December 29, 2000 [corrected January 1, 2001]

- 1 2 Dembner, "Striking a discord".

- ↑ Howie, "Bennington makes recovery its own way".

- ↑ June, Audrey Williams (October 22, 2004), "Bond-Rating Update", Chronicle of Higher Education: 40

- ↑ "Bennington: By the Numbers". Bennington.edu. 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ https://www.bennington.edu/news-and-features/bennington-recognized-princeton-review

- ↑ https://www.bennington.edu/news-and-features/forbes-tomorrows-hot-colleges

- ↑ - See more at: http://www.bennington.edu/about/outcomes/tops-list#sthash.jPPzCnbv.dpuf

- ↑ "Bennington: By The Numbers". Bennington College. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Bennington College". The Princeton Review. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ↑ "Bennington College Admissions". College Data. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bennington: Apply". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ "Bennington:Undergraduate Budget Sample". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ "Bennington College". Bennington College. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bennington College Tuition, Costs, & Financial Aid". College Data. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "Center for Creative Teaching". Bennington College. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Bennington Language Programs". Bennington College. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Graduate Programs". Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Poets & Writers Magazine

- ↑ Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program Archived December 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., bennington.edu; accessed October 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Bennington College Housing". Bennington College. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "Bennington College Map". Bennington College. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "US News: Bennington College Ratings". US News. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Bennington College Traditions". Unigo. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Silo". Bennington College. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ "The Bennington Free Press". Bennington College. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "A passage from India". The Guardian. London, UK. October 12, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ↑ Alan Arkin profile, IMDb.com; accessed October 3, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bennington College. |

Coordinates: 42°55′29″N 73°14′12″W / 42.924817°N 73.23673°W