Bryn Mawr College

| |

| Motto | Veritatem Dilexi (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | I Delight in the Truth |

| Type |

Private liberal arts college Women's college |

| Established | 1885 |

| Affiliation | None, formerly Quaker |

| Endowment | $853.0 million (2015)[1] |

| President | Kimberly Wright Cassidy[2] |

Academic staff | 158 full-time |

| Students | 1,771 |

| Undergraduates | 1,307 |

| Postgraduates | 464 |

| Location |

Bryn Mawr Lower Merion Twp, PA, USA |

| Campus | Suburban, 135 acres (55 ha) |

| Colors |

Yellow and White |

| Athletics | NCAA Division III – Centennial Conference |

| Mascot | Owl |

| Affiliations |

Seven Sisters CLAC Oberlin Group Annapolis Group WCC |

| Website | www.brynmawr.edu |

|

| |

|

Bryn Mawr College Historic District | |

| |

| Location | Morris Ave., Yarrow St. and New Gulph Rd., Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Coordinates | 40°1′35″N 75°18′49″W / 40.02639°N 75.31361°WCoordinates: 40°1′35″N 75°18′49″W / 40.02639°N 75.31361°W |

| Area | 49 acres (20 ha) |

| Built | 1885 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late Gothic Revival, Gothic, Collegiate Gothic |

| NRHP Reference # | 79002299[3] |

| Added to NRHP | May 4, 1979 |

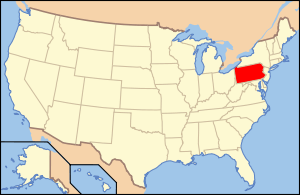

Bryn Mawr College (/ˌbrɪnˈmɑːr/ brin-MAR; Welsh: [ˌbrɨ̞nˈmaur])[4] is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, a community in Lower Merion Township, in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, four miles (6.4 km) west of Philadelphia.[5] The phrase bryn mawr means "big hill" in Welsh.,[6] literally "hill (bryn) big (mawr)".

Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, and is part of the Tri-College Consortium along with two other colleges founded by Quakers—Swarthmore College and Haverford College in the suburbs of Philadelphia. The school has an enrollment of about 1300 undergraduate students and 450 graduate students.

History

Bryn Mawr College is a private women's liberal arts college founded in 1885. The Graduate School is co-educational. It is named after the town of Bryn Mawr, in which the campus is located, which had been renamed by a representative of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Bryn Mawr was the name of an area estate granted to Rowland Ellis by William Penn in the 1680s. Ellis's former home, also called Bryn Mawr, was a house near Dolgellau, Merionnydd, Gwynedd, Wales. The College was largely founded through the bequest of Joseph W. Taylor, and its first president was James Evans Rhoads. Bryn Mawr was the first higher education institution to offer graduate degrees, including doctorates, to women. The first class included 36 undergraduate women and eight graduate students. Bryn Mawr was originally affiliated with the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), but by 1893 had become non-denominational.

In 1912, Bryn Mawr became the first college in the United States to offer doctorates in social work, through the Department of Social Economy and Social Research. This department became the Graduate School of Social Work and Social Research in 1970. In 1931, Bryn Mawr began accepting men as graduate students, while remaining women-only at the undergraduate level.

From 1921 to 1938 the Bryn Mawr campus was home to the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry, which was founded as part of the labor education movement and the women's labor movement. The school taught women workers political economy, science, and literature, as well as organizing many extracurricular activities.[7]

A June 3, 2008, article in The New York Times discussed the move by women's colleges in the United States to promote their schools in the Middle East. The article noted that in doing so, the schools promote the work of alumnae of women's colleges such as Hillary Clinton, Emily Dickinson, Diane Sawyer, Katharine Hepburn (Bryn Mawr Class of 1928) and Madeleine Albright. The Dean of Admissions of Bryn Mawr noted, "We still prepare a disproportionate number of women scientists [...] We’re really about the empowerment of women and enabling women to get a top-notch education." The article also contrasted the difference between women's colleges in the Middle East and "the American colleges [which] for all their white-glove history and academic prominence, are liberal strongholds where students fiercely debate political action, gender identity and issues like 'heteronormativity', the marginalizing of standards that are other than heterosexual. Middle Eastern students who already attend these colleges tell of a transition that can be jarring."[8]

The College celebrated its 125th anniversary of "bold vision, for women, for the world" during the 2010–2011 academic year.[9] In September 2010, Bryn Mawr hosted an international conference on issues of educational access, equity, and opportunity in secondary schools and universities in the United States and around the world.[10] Other festivities held for the anniversary year included publication of a commemorative book on 125 years of student life,[11] and, in partnership with the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program Mural Arts Program, creation of a mural in West Philadelphia highlighting advances in women's education.[12]

On February 9, 2015, the Board of Trustees announced approval of a working group recommendation to expand the undergraduate applicant pool. Trans women and intersex individuals identifying as women may now apply for admission, while trans men may not.[13] This official decision made Bryn Mawr the fourth women's college in the United States to accept trans women.[14]

College presidents

- 1885–1894 James E. Rhoads[15]

- 1894–1922 M. Carey Thomas

- 1922–1942 Marion Edwards Park

- 1942–1970 Katharine Elizabeth McBride

- 1970–1978 Harris L. Wofford

- 1978–1997 Mary Patterson McPherson

- 1997–2008 Nancy J. Vickers

- 2008–2013 Jane Dammen McAuliffe

- 2013–present Kimberly Wright Cassidy

Campus

The campus was designed in part by noted landscape designers Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, and has subsequently been designated an arboretum (the Bryn Mawr Campus Arboretum). In 2011, Travel+Leisure named Bryn Mawr as one of the most beautiful college campuses in the United States.[16]

Student residences

The majority of Bryn Mawr students live on campus in residence halls. Many of the older residence halls were designed by Cope & Stewardson and are known for their Collegiate Gothic architecture, modeled after Cambridge University. Each is named after a county town in Wales: Brecon, Denbigh (1891), Merion (1885), and Radnor (1887), and Pembroke East and West (1892). Rhoads North and South was named after the college's first president, James E. Rhoads; Rockefeller is named after its donor, John D. Rockefeller. Erdman was opened in 1965, designed by architect Louis Kahn. In addition, students may choose to live in Batten House (an environmentally friendly co-op). Perry House, which was originally established as the Spanish language house in 1962, was redefined as the Black Cultural Center in the 1970s. In 2015, Perry House was relaunched by the college in the former French tower of Haffner, which had undergone renovations and reconstruction the previous year.[17] Along with Perry, now known as the Enid Cook '31 Center, a new residence hall was built where the old Haffner Language and Culture House once stood.

Glenmede (formerly graduate student housing) is an estate located about a half mile from the main campus which was available housing for undergraduate students. In 2007, it was sold to a conservation buyer as the annual costs of upkeep were too great for the college.[18]

Libraries

Bryn Mawr's library holdings are housed in the Mariam Coffin Canaday Library (opened 1970), the Rhys Carpenter Library (opened 1997), and the Lois and Reginald Collier Science Library (opened 1993). TRIPOD, the online library catalog, automatically accesses holdings at Haverford and Swarthmore.

Blanca Noel Taft Memorial Garden

In 1908, John C. Olmsted designed a private garden for M. Carey Thomas adjoining the Deanery. The garden was later modified and renamed as the Blanca Noel Taft Memorial Garden. In its current form, the garden is a small, serene enclosure with two wall fountains, one with a small basin and the other with a sunken reflecting pool. The decorative wall tiles above the smaller wall fountain and basin were purchased from Syria.[19]

Erdman Hall Dormitory

In 1960, architect Louis I. Kahn and Bryn Mawr College president, Katharine Elizabeth McBride, came together to create the Erdman Hall dormitory.[20]

For over a year, Kahn and his assistants struggled to translate the college’s design program of 130 student rooms and public spaces into a scheme (well documented by the letters written between McBride and Kahn). The building comprises three geometrical square structures, connected at their corners. The outer walls are formed by interlocking student rooms around three inner public spaces: the entry hall, dining hall and living hall. These spaces receive light from towering light monitors.

The Marjorie Walter Goodhart Theater

The Marjorie Walter Goodhart Theater houses a vaulted auditorium designed by Arthur Ingersoll Meigs of Mellor, Meigs & Howe, two smaller spaces that are ideal for intimate performances by visiting artists, practice rooms for student musicians, and the Office for the Arts. The building's towers and gables, friezes, carvings and ornamental ironwork, designed by Samuel Yellin, were done in the gothic revival style.[21][22] In the fall of 2009, the College completed a $19 million renovation of Goodhart, which included expanded stage and rehearsal space, updated sound and lighting, a teaching theater, and renovated seating for audiences.[23]

M. Carey Thomas Library

Named after Bryn Mawr's first Dean and second president, the M. Carey Thomas Library was used as the primary campus library until 1970, when Mariam Coffin Canaday Library opened. The Great Hall (formerly the reading room of the library) was designed by Walter Cope (of Cope and Stewardson) in 1901 and built by Stewardson and Jamieson several years later, although M. Carey Thomas played a large part in its construction. Today, it is a space for performances, readings, lectures, and public gatherings. The M. Carey Thomas Library encloses a large open courtyard called "The Cloisters", which is the site of the College's traditional Lantern Night ceremony. The cremated remains of M. Carey Thomas and Emmy Noether are located in the Cloisters. Georgiana Goddard King is also buried in the cloister.[24] The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1991.[25][26]

Rhys Carpenter Art and Archaeology Library

Named for Bryn Mawr’s late professor of Classical Archaeology, the Rhys Carpenter Library was designed by Henry Myerberg of New York and opened in 1997. The space is connected to the rear of the M. Carey Thomas Library. The entrance is a four-story atrium. Names of art and archaeology faculty are displayed on the main wall of the atrium, along with a series of plaster casts of the metopes of the Parthenon. Most of the stacks, study areas, lecture halls and seminar rooms are located underground. The roof comprises a wide grassy area used for outdoor concerts and picnics. The building won a 2001 Award of Excellence for Library Architecture from the Library Administration and Management Association and the American Institute of Architects. Carpenter Library also houses the College's renowned collections in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology, History of Art, and Classics.[27] The building also contains a large lecture hall and several seminar rooms.[22][28]

The Deanery

The Bryn Mawr College Deanery was the campus residence of the first Dean and second President of Bryn Mawr College, M. Carey Thomas, who maintained a home there from 1885 to 1933. Under the direction of Thomas, the Deanery was gradually enlarged and elaborately decorated with the assistance of the American artist Lockwood de Forest and furnished with art from Thomas' world travels. From 1933 until 1968, the Deanery served as the Alumnae Center and Inn for the college. The building was demolished in the spring of 1968 to make space for the construction of Canaday Library, which stands on the site today. At the time of its demolition, many of the Deanery's furnishings were re-located to Wyndham, an 18th-century farmhouse (with several modern additions) which became the college's new Alumnae Center.

Organization

Bryn Mawr undergraduates largely govern themselves in academic and social matters via the Self-Government Association. A significant aspect of self-government is the Academic Honor System (honor code). The Honor Code is a set of principles that stress mutual respect and academic integrity. Students ratify the code each year, agree to adhere to it, and enforce its provisions.

Along with Haverford College, Bryn Mawr forms the Bi-College Community. Students in the "Bi-Co" enjoy unlimited cross-registration privileges and may choose to major at the other institution. The two institutions join with Swarthmore College to form the Tri-College Consortium, opening the Swarthmore course catalog to interested Bryn Mawr students as well. Free shuttles are provided between the three campuses. There is the Blue Bus between Bryn Mawr and Haverford College, and a van, known to the students as the "Swat Van", that travels among the three colleges.

In addition, the College is affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania through a special association known as the Quaker Consortium, allowing Bryn Mawr students to take classes there. Additionally, Bryn Mawr students in the Growth and Structure of Cities department may earn a Bachelor of Arts at Bryn Mawr and a master's degree in city planning at Penn through the 3–2 Program in City and Regional Planning. Students also are allowed to take classes related to their major at the nearby Villanova University through a specific registration process.

Academics

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[29] | 70 |

| Liberal arts colleges | |

| U.S. News & World Report[30] | 31 |

| Washington Monthly[31] | 6 |

Bryn Mawr is a small, four year, residential baccalaureate college.[32] Although the college offers several graduate programs, the majority of enrollments are from students enrolled in the undergraduate arts and sciences program. The college granted 331 bachelor's degrees, 106 master's degrees, and 21 doctoral degrees in 2009.[33]

Students at Bryn Mawr are required to complete divisional requirements in the social sciences, natural sciences (including lab skills) and humanities. In addition, they must complete one year of a foreign language beyond the entry level and fulfill a quantitative skills requirement and an Emily Balch Seminar requirement. The Emily Balch Seminars are similar to courses in freshman composition at other institutions. The seminars stress development of critical thinking skills and are discussion-based, with "intensive reading and writing."[34]

Admission to Bryn Mawr is classified as "more selective, lower transfer in."[32] In 2009, Bryn Mawr received 2,276 undergraduate applications, admitted 1107 (48.6%), and enrolled 362 (32.7%). First year students had interquartile ranges of 600–700 on reading, 580–680 on math, and 620–700 on writing on the SAT.[33] The four-year graduation rate is 81.4% and the six-year rate is 86.3%.[33] The student body comprises 1,283 female undergraduate students and the graduate program comprises 464 graduate students (21.3% of them male).

Community College Connection Program

The Community College Connection Program, shortened to simply C3, was created through a grant provided by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation in 2011. A partnership between Montgomery County Community College, the Community College of Philadelphia, and Bryn Mawr College, C3 linked the three schools by providing low-income students with exceptional grades at Montgomery County Community College and the Community College of Philadelphia the opportunity to attend Bryn Mawr to complete their bachelor's degree.[35]

Traditions

The four major traditions held at Bryn Mawr College include Parade Night, which traditionally took place on the first day of classes each academic year, but has been moved to the Friday of the first week of classes; Lantern Night, which takes place in late October or early November; Hell Week, which takes place in mid-February; and May Day, which takes place on the Sunday after classes end in the spring semester.[36] The Dar Williams song "As Cool As I Am" has recently become part of the tradition of May Day; it is played during the "May Hole" celebration, which is the feminist answer to the traditional may poles displayed on campus.[37] In the bi-campus newspaper shared with Haverford College, one student called it the college's unofficial anthem.[38]

Bryn Mawr students gather quarterly for "Step Sings," or evenings spent outside Taylor Hall, singing hymns, traditional feminist songs and contemporary songs. Step Sings follow each major tradition.[36]

Two Traditions Mistresses or Masters, depending on the individual's gender, elected by the student body, are in charge of organizing and running traditions.[39]

In addition to events, Bryn Mawr's traditions extend to superstitions around the campus, some of which date back to the opening of the college in 1885.[40]

Sustainability

Bryn Mawr has signed the American College and University President's Climate Commitment, and in doing so, the school agreed to make all new buildings comply with a LEED silver standard or higher; to purchase Energy Star products whenever possible; and to provide and encourage the use of public transportation.[41] The school's dining halls strive to be environmentally sustainable by working to expand their local and organic offerings, recycling in all dining areas, and recycling used fry oil as bio-diesel fuel. The dining halls previously offered biodegradable takeout containers, but reverted to Styrofoam in the 2009/10 academic year. Additionally, all leftover food is donated to a local food bank.[42] On the College Sustainability Report Card 2009, published by the Sustainable Endowments Institute, Bryn Mawr received a C+. The school's highest category score was an A in Investment Priorities, since Bryn Mawr invests in renewable energy funds, but the score was brought down by lower grades in categories like Green Building (in which the school earned a D, since the campus currently features no green buildings).[43]

Athletics

Bryn Mawr fields intercollegiate teams in badminton, basketball, cross country, field hockey, lacrosse, rowing, rugby, soccer, swimming, tennis, track and field, and volleyball. The badminton team won national intercollegiate championships in 1996 and 2008.[44][45] The mascot of the college is the owl, the symbol of Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom.

Notable alumnae and faculty

- Alumnae

A large number of Bryn Mawr alumnae have gone on to become notable in their respective fields. The list includes Drew Gilpin Faust (class of 1968), the first woman president of Harvard University; Hanna Holborn Gray (1950), the first woman president of a major research university (University of Chicago); modernist poets H.D. (attended), and Marianne Moore (1909); classics scholar Edith Hamilton (M.A. 1894); author, social activist and feminist Grace Lee Boggs (Ph.D. 1940); Nobel Peace Prize winner Emily Greene Balch (1889); geneticist Nettie Stevens (Ph.D. 1903); mathematician Ada Isabel Maddison (Ph.D. 1896); 1891 Fellow in Mathematics Ruth Gentry; artist Anne Truitt (1943); author Ellen Kushner (attended); economist Alice Rivlin (1952); four-time Academy Award-winning actress Katharine Hepburn (1928); bestselling novelist Andrea Portes (1993); Jo Ellen Johnson Parker (B.A., 1975), the 10th president of Sweet Briar College.

- Faculty

Notable faculty include Woodrow Wilson, chemists Arthur C. Cope and Louis Fieser, Arthur Lindo Patterson of the Patterson function, Edmund Beecher Wilson, Thomas Hunt Morgan, historian Caroline Robbins, mathematician Emmy Noether, classicist Richmond Lattimore, the Spanish philosopher José Ferrater Mora, the poet Karl Kirchwey.[46][47]

Further reading

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas. New York: Knopf, 1994.

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: design and experience in the women's colleges from their nineteenth-century beginnings to the 1930s; 2nd ed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

References

- ↑ As of June 30, 2015. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2015 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2014 to FY 2015" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2016.

- ↑ Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-10.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Mackey & Mackey (1922) The Pronunciation of 10,000 Proper Names; also example at e-speech site

- ↑ "Bryn Mawr College". Google Maps.

- ↑ Not "high hill", as is often mistakenly given as the translation; Bryn Uchel translates to "high hill"

- ↑ "1921 The Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers". fcis.oise.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Lewin, Tamar (2008-06-03). "'Sisters' Colleges See a Bounty in the Middle East". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Plans for 125th Anniversary Include International Conference on Women's Education". news.brynmawr.edu. Bryn Mawr Now. 2010-04-08. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Heritage and Hope: Women's Education in a Global Context". brynmawr.edu. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Bryn Mawr College: Bryn Mawr's 125th Anniversary Celebration". brynmawr.edu. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Bryn Mawr College to Sponsor Mural Highlighting Advances in Women's Education as Part of Its 125th Anniversary Celebration". news.brynmawr.edu. Bryn Mawr Now. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ↑ A Letter from Bryn Mawr Board Chair Arlene Gibson. brynmawr.edu. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ Mitch Kellaway (11 February 2015). "Bryn Mawr Becomes Fourth U.S. Women's College to Accept Transgender Students". Advocate.com. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ James E. Rhoads. Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "America's most beautiful college campuses", Travel+Leisure (September 2011)

- ↑ "Saying Goodbye to Perry House While Looking Ahead to the "New Perry"". Bryn Mawr Now. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ↑ Glenmede Saved From Destruction and Over-Development. Save Ardmore Coalition (2005-10-13). Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Bryn Mawr College Campus Plan – John Olmsted. Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Erdman Hall Dormitories". The Architecture Week's Great Building Collection.

- ↑ Bryn Mawr College | Visiting Campus. Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- 1 2 The First 300: The Amazing and Rich History of Lower Merion (Part 18). Lowermerionhistory.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ Bryn Mawr Now: To Inaugurate a Reconceived Goodhart, Bi-College Theater Production Probes Language, Space Retrieved April 27, 2010

- ↑ Mann, Janice (2005). Women Medievalists and the Academy. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 121.

- ↑ "M. Carey Thomas Library". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Photos from 1936, 1980, 1983, and undated, to accompany National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: M. Carey Thomas Library (text not available)" (pdf). National Park Service.

- ↑ Special Collections Website. Retrieved on 2014-05-20

- ↑ Bryn Mawr College | Visiting Campus. Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "America's Top Colleges". Forbes. July 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Best Colleges 2017: National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 12, 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Rankings - National Universities - Liberal Arts". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- 1 2 "Bryn Mawr College – Carnegie Classifications". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- 1 2 3 "Common Data Set 2009-2009" (PDF). Bryn Mawr College. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ↑ "The Emily Balch Seminars". Bryn Mawr College Undergraduate Courses. Bryn Mawr College. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ Ratneshwar, Priya (February 2014). "A Commitment to Access". Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin: 12.

- 1 2 "Traditions". Bryn Mawr College. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Clea Benson. "Modern Changes To A Vintage Rite Bryn Mawr Students' Spring Frolic Includes A Celebration Of Womanhood.". Philly.com. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Molly Parzen (6 April 2010). "Dar Williams at the Mawr". The Bi-College News. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ "Student Activities: Traditions". brynmawr.edu. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

The Traditions Mistresses, elected officers of the SGA, organize the traditions throughout the academic year. Pamela Gassman and Dijia Chen are the 2014-2015 Traditions Mistresses.

- ↑ Bryn Mawr College Student Activities. Brynmawr.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "Implementation Profile for Bryn Mawr College". Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ "Sustainability". Bryn Mawr College. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ Bryn Mawr College – Green Report Card 2009. Greenreportcard.org (2007-06-30). Retrieved on 2011-06-18.

- ↑ "1996 NE Regional & National Collegiate Championships". Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ "Badminton wins IBA championships". Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ "Faculty 2010–2011". Bryn Mawr College. 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ↑ Karen Heller (May 1, 2003). "Bryn Mawr shows creative side as it makes way for arts". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bryn Mawr College. |

- Official website

- Official athletics website

- The Bi-College News, Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges' Student Newspaper

- The Tri-College Art and Artifacts Database

- The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation website