Hampden–Sydney College

|

Seal of Hampden–Sydney College | |

Former names | Hampden—Sidney College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Huc venite iuvenes ut exeatis viri |

Motto in English | Latin: Come here as boys so you may leave as men |

| Type |

Private liberal arts college Men's college |

| Established | November 10, 1775 |

| Affiliation | Presbyterian [1] |

| Endowment | $154.6 million[2] |

| President | Larry Stimpert |

| Provost | Walter McDermott (Interim) |

Academic staff | 128 |

| Undergraduates | 1,105[3] |

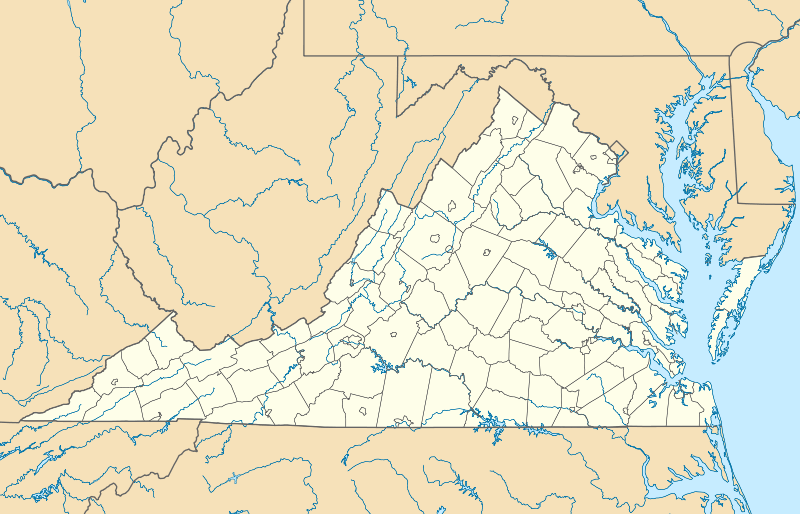

| Location |

Hampden Sydney, Virginia, United States 37°14′31″N 78°27′37″W / 37.242041°N 78.460279°WCoordinates: 37°14′31″N 78°27′37″W / 37.242041°N 78.460279°W |

| Campus | Rural, 1,200 acres (4.86 km2) |

| Colors | Garnet and Grey |

| Athletics | NCAA Division III – ODAC |

| Sports | 9 varsity teams |

| Nickname | Tigers |

| Affiliations |

APCU Annapolis Group |

| Website |

www |

Hampden–Sydney College, also known as H–SC, is a liberal arts college for men located in Hampden Sydney, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1775, Hampden–Sydney is the oldest private charter college in the Southern U.S., the 10th oldest college in the U.S., the last college founded before the American Revolution, and one of only three four-year, all-men's liberal arts colleges in the United States. Hampden–Sydney College is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register.

Overview

Hampden–Sydney enrolls approximately 1,100 students from 30 states and several foreign countries and emphasizes a rigorous, traditional liberal arts curriculum.[4]

Honor Code

Along with Wabash College and Morehouse College, Hampden–Sydney is one of only three remaining traditional all-male colleges in the United States and is noted as a highly regarded all-male institution of higher education in North America.[5] The school's mission is to "form good men and good citizens in an atmosphere of sound learning". As such, Hampden–Sydney has one of the strictest honor codes of any college or university. Upon entering as a student, each man pledges for life that he will not lie, cheat, steal, nor tolerate those who do. The pledge takes place during a ceremony in which the entering class sits in absolute silence while each man, when his name is called, comes forward and signs the pledge. This simply worded code of behavior applies to the students on and off campus. The Honor Code system is student-run, allowing for a trial of peers, adjudicated by a court of students. Students convicted of an honor offense face anywhere between 1 and 3 semesters of suspension or expulsion. Notably, a separate Code of Student Conduct covers "behavioral" infractions such as attempting to drink underage that do not rise to the level of an honor offense (which only arise if deception or theft is involved). Thus, in effect, a two-tier system of student discipline is maintained; the Code of Student Conduct (regarding policies on parking or drinking) is enforced by the Dean of Students' Office with the help of the Student Court while the Honor Code system (with more serious penalties for lying, cheating, or stealing) is maintained exclusively by the students themselves. Though grievous violation of the Code of Student Conduct may result in expulsion, it is rare that any student is expelled except by sentencing of the Honor Court.

Western Culture Program

All Hampden–Sydney students must take a three-course Western Culture sequence, which introduces them to some of the great works and historical events from Greece and Rome through present times. There are few dedicated instructors of western culture. Instead the program draws on professors from all disciplines. This program is "the bedrock of Hampden–Sydney's liberal arts program and one of the most important of its core academic requirements." [6]

Rhetoric Program

Every student must prepare for and pass the Rhetoric Proficiency Exam, which consists of a three-hour essay that is graded for grammatical correctness and the coherence, quality, and style of the argument.[7] To prepare, the college requires each student to pass two rhetoric classes that are usually taken during the first two semesters. The rhetoric requirement is the same for students who decide to major in the humanities as for those who follow a course of studies in economics. After graduating, many alumni have stated that the Rhetoric Program was the most valuable aspect of the Hampden–Sydney education.

History

Founding and early years

The college's founder and first president, Samuel Stanhope Smith, was born in Pequea, Pennsylvania. He graduated as a valedictorian from the College of New Jersey in 1769, and he went on to study theology and philosophy under John Witherspoon, whose daughter he married on June 28, 1775. In his mid-twenties, working as a missionary in Virginia, Smith persuaded the Hanover Presbytery to found a school east of the Blue Ridge, which he referred to in his advertisement of September 1, 1775 as “an Academy in Prince Edward...distinguished by the Name of HAMPDEN–SIDNEY".[8] The school, not then named, was always intended to be a college-level institution; later in the same advertisement, Smith explicitly likens its curriculum to that of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). “Academy” was a technical term used for college-level schools not run by the established church.[9]

As the college history indicates on its web site, "The first president, at the suggestion of Dr. John Witherspoon, the Scottish president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), chose the name Hampden–Sydney to symbolize devotion to the principles of representative government and full civil and religious freedom which John Hampden (1594–1643) and Algernon Sydney (1622–1683) had outspokenly supported, and for which they had given their lives, in England's two great constitutional crises of the previous century. They were widely invoked as hero-martyrs by American colonial patriots, and their names immediately associated the College with the cause of independence championed by James Madison, Patrick Henry, and other less well-known but equally vigorous patriots who composed the College's first Board of Trustees."

Classes at Hampden–Sydney began in temporary wooden structures on November 10, 1775, on the eve of American Independence, moving into its three-story brick building early in 1776. The college has been in continuous operation since that date, operating under the British, Confederate, and United States flags. In fact, classes have only been canceled six times: for a Civil War skirmish on campus, for a hurricane that knocked a tree into a dormitory building, thrice due to snowstorms, and once for an outbreak of norovirus. Since the college was founded before the proclamation of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, it was eligible for an official coat of arms and armorial bearings from the College of Arms of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. Through gifts from the F. M. Kirby Foundation, Professor John Brinkley ('59), in whose honor the "achievement of arms" was given, liaised with Mr. John Brooke-Little, then the Richmond Herald, in designing the arms for the college. The Latin text of the "letters patent" conferring the arms is dated July 4, 1976; Mr. Brooke-Little—who with the Queen's special permission appeared in full herald's uniform—made the presentation on Yorktown Day, October 19, 1976, at the college.[10]

Despite the difficult and financially strapped first years resulting from the Revolutionary War, the college survived with sufficient viability to be granted a charter by the Virginia General Assembly in 1783—the oldest private charter in the South. Patrick Henry, then Governor of Virginia, encouraged the passage of the charter, and wrote into it an oath of allegiance to the new republic, required of all professors.

The college was founded by alumni of Princeton University. Both Patrick Henry, who did not attend any college, and James Madison, a Princeton alumnus, were elected trustees in the founding period before classes began. Smith hired his brother, John Blair Smith, and two other recent Princeton graduates to teach. Samuel Stanhope Smith would later become president of Princeton University. John Blair Smith would become the second president of Hampden–Sydney and later the first president of Union College.

19th century

Hampden–Sydney became a thriving college while located in southside Virginia, which led to expansion. In 1812, the Union Theological Seminary was founded at Hampden–Sydney College. The seminary was later moved to Richmond, Virginia and is currently the Union Theological Seminary & Presbyterian School of Christian Education. In 1838, the medical department of Hampden–Sydney College was founded—the Medical College of Virginia, which is now the MCV Campus of Virginia Commonwealth University. Among the early nineteenth-century leaders were John Holt Rice, who founded the seminary, Jonathan P. Cushing, and Reverend James Marsh. In those years the intellectual culture at HSC spanned from leading southern, anti-slavery writers like Jesse Burton Harrison and Lucian Minor to leading proslavery writers, such as George A. Baxter and Landon Garland.[12] During this time, the college constructed new buildings using Federal-style architecture with Georgian touches. This is the style of architecture still used on the campus.

At the onset of the American Civil War, Hampden–Sydney students formed a company in the Virginia Militia. The Hampden–Sydney students did not see much action but rather were “captured, and...paroled by General George B. McClellan on the condition that they return to their studies".[13]

20th century

During World War II, Hampden–Sydney College was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a commission.[14]

The college has hosted a wide array of noteworthy musicians. Bruce Springsteen, the Allman Brothers, Dave Matthews Band, Widespread Panic, Bruce Hornsby, Pretty Lights, and Government Mule were among the popular visitors to Hampden–Sydney throughout the latter half of the twentieth century.

On May 11, 1964, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy visited Hampden–Sydney College to speak with students.,[15] and U.S. Vice President George H.W. Bush gave the May 1985 commencement address.

Name

Presumably under the influence of his mentor and father-in-law Witherspoon,[16] Smith named the college for two English champions of liberty, John Hampden (1594–1643) and Algernon Sydney (1622–1683). Hampden lost his life in the battle of Chalgrove Field during the English Civil War. Sydney, who wrote "Discourses Concerning Government", was beheaded by order of Charles II following his (unproven) implication in a failed attempt to overthrow the king. These proponents of religious and civil liberties were much admired by the founders of the college, all of whom were active supporters of the cause of American independence.

Campus

|

Hampden-Sydney College Historic District | |

|

The grounds of Hampden–Sydney | |

| |

| Location | Bounded approximately by the Hampden–Sydney College campus, Hampden Sydney, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 270 acres (110 ha) |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Federal |

| NRHP Reference # | 70000822[17] |

| VLR # | 073-0058 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 26, 1970 |

| Designated VLR | December 2, 1969[18] |

The college has expanded from its original small cluster of buildings on 100 acres (0.4 km²) to a campus of over 1300 acres (5.25 km²). Before 2006, the college owned 660 acres (2.7 km²). In February 2006, the college purchased 400 acres (1.6 km²) which include a lake and Slate Hill Plantation, the historic location of the college's founding. The campus is host to numerous federal style buildings. Part of the campus has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.[19]

Student life

Culture

As one of only a few higher educational institutions for men, and being older than the nation in which it is located, Hampden–Sydney College has a unique culture. Students are also issued a copy of To Manner Born, To Manners Bred: A Hip-pocket Guide to Etiquette for the Hampden–Sydney Man,[20] which covers everything from basic manners, how to greet and introduce people, how to respond to invitations, how to dress, the difference between a black-tie and white-tie event, how to choose a wine, etc. The college publishes the book as a useful tool for existing successfully in a variety of social settings.[21] Tailgating is central to Hampden–Sydney's culture each fall and has been featured in Town and Country.[22]

Clubs and organizations

According to the college website, there are over 40 clubs on campus. Each club is run by the students. There are political clubs, sports clubs, religious clubs, a student-run radio station, a pep band, and multiple social fraternities. There are also volunteer groups such as Habitat for Humanity and Rotaract.

The college campus is home to a volunteer fire department, which provides fire suppression service and non-transport basic life support EMS to Prince Edward County and the college, as well as assisting the Farmville fire department at fires within the town limits. HSVFD, Company 2, is located on the south end of campus near the water tower and the physical plant. Contrary to popular belief, and despite its location and the fact that 90% of the membership comes from college faculty, staff, and students, the fire department is, in fact, not affiliated with the college.[23]

Union-Philanthropic Literary Society (UPLS) is the oldest student organization at Hampden–Sydney College. Established on September 22, 1789, it is the nation's second oldest literary and debating society still in existence today.

Greek life

For freshmen, rush begins in the first semester and pledging takes place in the spring. If a student chooses not to rush and/or pledge as a freshman, sophomores and juniors may pledge in the fall or spring. Roughly 47% of the student body is involved in Greek life.[24] Beta Theta Pi used Atkinson Hall (built 1834) as a fraternity house when it came to campus in 1850 possibly making it one of the first fraternity houses in North America. Chi Psi is widely believed to have created the first fraternity house in 1845 at the University of Michigan.[25][26]

The following Greek groups were active on campus as of December 2014:

- Chi Phi, XΦ[27]

- Pi Kappa Alpha, ΠKA[27]

- Alpha Chi Sigma, AXΣ[28]

- Delta Kappa Epsilon, ΔΚΕ[29]

- Kappa Sigma, KΣ[27]

- Sigma Alpha Epsilon, ΣΑΕ[27]

- Phi Gamma Delta, Phi Gam[27]

- Kappa Alpha Order KA[27]

- Sigma Nu, ΣN[27]

- Beta Theta Pi, ΒΘΠ (inactive) [30]

- Theta Chi, ΘX[27]

- Sigma Chi, ΣX[27]

- Lambda Chi Alpha, ΛΧΑ (inactive) [27]

In addition to the social and professional fraternities listed above, Hampden–Sydney also has chapters of Phi Beta Kappa, the Academic Honor Society;[31] Phi Alpha Theta, the national history honor society;[32] Pi Sigma Alpha, the national political science honor Society;[33] Omicron Delta Kappa, a national leadership honor society[34] and Alpha Psi Omega, a national honors society for theatre arts.[35]

Housing

The Elliott House is reserved for Honor Students who choose to live there. Although an overwhelming majority of students live on campus or in campus-owned housing, the school does permit a small number of students (usually upperclassmen) to live off-campus. In addition, some students also rent rooms in local campus homes.

Athletics

Hampden–Sydney College teams participate as a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Division III. The Tigers are a member of the Old Dominion Athletic Conference (ODAC). Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving and tennis.

Hampden–Sydney's rivalry with Randolph-Macon College is one of the longest-running college rivalries in the United States. "The Game" is often referred to as the oldest small-school football rivalry in the South,[36] with the first match up having been played in 1893. Athletic events involving the two schools are fiercely competitive, and the week prior to "The Game" between Hampden–Sydney and Randolph-Macon is known as "Beat Macon Week".[37]

Presidents

The following is a list of the Presidents of Hampden–Sydney College from its opening in 1775 until the present.[38]

| # | Name | Term begin | Term end | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samuel Stanhope Smith | 1775 | 1779 | |

| 2 | John Blair Smith | 1779 | 1789 | |

| * | Drury Lacy | 1789 | 1797 | Vice President and Acting President |

| 3 | Archibald Alexander | 1797 | 1806 | |

| * | William S. Reid | 1807 | 1807 | Vice President and Acting President |

| 4 | Moses Hoge | 1807 | 1820 | |

| 5 | Jonathan P. Cushing | 1821 | 1835 | Acting President (1820–1821) |

| * | George A. Baxter | 1835 | 1835 | Acting President |

| 6 | Daniel Lynn Carroll | 1835 | 1838 | |

| 7 | William Maxwell | 1838 | 1845 | |

| 8 | Patrick J. Sparrow | 1845 | 1847 | |

| * | S. B. Wilson | 1847 | 1847 | Acting President |

| * | F. S. Sampson | 1847 | 1848 | Acting President |

| * | Charles Martin | 1848 | 1849 | Acting President |

| 9 | Lewis W. Green | 1849 | 1856 | |

| * | Albert L. Holladay | 1856 | 1856 | Died before taking office |

| * | Charles Martin | 1856 | 1857 | Acting President |

| 10 | John M. P. Atkinson | 1857 | 1883 | |

| 11 | Richard McIlwaine | 1883 | 1904 | |

| * | James R. Thornton | 1904 | 1904 | Acting President |

| * | W. H. Whiting, Jr. | 1904 | 1905 | Acting President |

| * | J. H. C. Bagby | 1905 | 1905 | Acting President |

| 12 | James G. McAllister | 1905 | 1908 | |

| * | W. H. Whiting, Jr. | 1908 | 1909 | Acting President |

| 13 | Henry T. Graham | 1909 | 1917 | |

| * | Ashton W. McWhorter | 1917 | 1919 | Acting President |

| 14 | Joseph DuPuy Eggleston | 1919 | 1939 | |

| 15 | Edgar Graham Gammon | 1939 | 1955 | |

| 16 | Joseph Clarke Robert | 1955 | 1960 | |

| 17 | Thomas Edward Gilmer | 1960 | 1963 | |

| 18 | Walter Taylor Reveley II | 1963 | 1977 | |

| 19 | Josiah Bunting III | 1977 | 1987 | |

| 20 | James Richard Leutze | 1987 | 1990 | |

| * | John Scott Colley | 1990 | 1991 | Acting President |

| 21 | Ralph Arthur Rossum | 1991 | 1992 | Resigned after nine months |

| 22 | Samuel V. Wilson | 1992 | 2000 | |

| 23 | Walter M. Bortz III | 2000 | 2009 | |

| 24 | Christopher B. Howard | 2009 | 2016 | |

| * | Dennis G. Stevens | 2016 | 2016 | Acting President |

| 25 | John Lawrence Stimpert | 2016 | Sitting |

Notable alumni

Rankings

Forbes

- Forbes ranked Hampden–Sydney #4 in its 2010 ranking of the best private colleges in the South. It ranked #6 among Forbes 20 best colleges in the South.[39]

- Forbes awarded Hampden–Sydney with an "A" grade in its 2016 Forbes College Financial Grades; an evaluation methodology designed to "measure the fiscal soundness of nearly 900 four-year, private, not-for-profit colleges with at least 500 students".[40]

Princeton Review

- The Princeton Review ranked Hampden–Sydney #8 in its 2016 rankings of Best Alumni Network.[41]

U.S. News & World Report

- U.S. News & World Report ranked Hampden–Sydney #108 in its 2016 rankings of the top National Liberal Arts Colleges.[42]

See also

- Hampden–Sydney College alumni

- Wabash College

- Morehouse College

References

- ↑ "H-SC – College Presbyterian Church – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ As of June 30, 2015. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2015 Endowment Market Value and Percentage Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2014 to FY 2015" (PDF). 2015 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments. National Association of College and University Business Officers. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ↑ As of 2014–2015 academic year. "Good news presented at a recent Richmond alumni meeting.". Hampden–Sydney College. Hampden–Sydney College. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ↑ Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Whitman, David. Wabash College, One of a Dying Breed, U.S. News & World Report, January 31, 1999.

- ↑ "H–SC | H–SC Receives Mellon Grant for Western Culture | Hampden–Sydney College". Hsc.edu. October 1, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ "H–SC – Rhetoric Proficiency Exam – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1 September 1775.

- ↑ Brinkley, 5 and Appendix I, 847–50

- ↑ "H-SC – Coat of Arms – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "H-SC – Coat of Arms – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ A.J. Morrison ed., Six Addresses on the State of Letters and Science in Virginia 3–4 (Roanoke, 1917).

- ↑ Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "An army of good men". Hampden Sydney, Virginia: Hampden–Sydney College. 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ↑ Louis Briel '66 Remembers Kennedy on YouTube

- ↑ Brinkley, 15

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ↑ Archived November 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Thomas Shomo, 'To Manner Born, To Manners Bred: A Hip-pocket Guide to Etiquette for the Hampden–Sydney Man', 1978, Hampden–Sydney College.

- ↑ "Hampden–Sydney College Booklet" (PDF). Hsc.edu. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ English, Micaela. "Hampden Sydney Football – Tailgating Photos". Townandcountrymag.com. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ "UIȒPo^h". Hsvfd.org. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "College Profile : Hampden–Sydney College". Collegedata.com. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Hampden Sydney College: Student Life". Museumstuff.com. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "H-SC – Social Fraternities – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ↑ "H-SC – Alpha Chi Sigma – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Hampden–Sydney Colony of Delta Kappa Epsilon at Hampden–Sydney College - Hampden–Sydney Colony, Delta Kappa Epsilon, Hampden–Sydney College, chapterspot fraternity websites, chapterspot sorority websites, chapterspot.com". Hsc.dekeunited.org. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived October 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.hsc.edu/Student-Life/Activities/Honor-Fraternities/Phi-Alpha-Theta.html

- ↑ Archived June 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "H-SC – Omicron Delta Kappa – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Archived October 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Oldest small-school football rivalry in the south now 'goes across all sports' – College Sports – ESPN". ESPN.com. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Editor. "HSC Tigers Football: Beat Macon Week". Hsctigerfootball.blogspot.com. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ "H-SC – Presidents of the College – Hampden–Sydney College". Hampden–Sydney College. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Christina Ferro and Archana Rajan (January 19, 2010). "The Best Colleges In The South". Forbes. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ Matt Schifrin (July 6, 2016). "2016 Forbes College Financial Grades: E Through M". Forbes. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Best Alumni Network". The Princeton Review. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ "National Liberal Arts Colleges". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

Bibliography

- Brinkley, John Luster. On This Hill: A narrative history of Hampden Sydney College, 1774–1994. Hampden–Sydney: 1994. ISBN 1-886356-06-8