A significant number of science fiction works have explored the imaginative possibilities of binary or multiple star systems. Many real stars near the Sun belong in this category. This article is about imaginary binary and multiple star systems in science fiction.

Binary and multiple stars

Binary stars

Artist's impression of the view from a (hypothetical) moon of planet

HD 188753 Ab (upper left), which orbits in a

triple star system. The brightest component star (A) has just set. The binary pair HD 188753 BC lingers in the sky.

A binary star is a star system consisting of two stars orbiting around their common center of mass. The brighter star is called the primary and the lesser is its companion star, or secondary. A binary star is one kind of double star : a star that resolves visually into two separate stars that are very close together as seen from the Earth; the other type of double star is an optical double, consisting of stars of significantly differing distances or velocities which merely appear near each other in the sky but are dynamically unrelated.

In astronomy, the components of binary stars are denoted by the suffixes A and B appended to the system's designation, A denoting the primary and B the secondary. The suffix AB may be used to denote the pair (for example, the binary star Alpha Centauri AB consists of the components Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B). Additional letters, such as C, D, and so on, may be used for systems with more than two stars (see graphic).[1] In cases where the binary star has a Bayer designation and is widely separated, it is possible that the members of the pair will be designated with superscripts; an example is ζ Reticuli, whose components are ζ1 Reticuli and ζ2 Reticuli (see Alien, directed by Ridley Scott). Note that, with a single exception (Honor Harrington by David Weber, below), the authors of fiction represented in this article do not follow the astronomical convention; when they name their stars at all, they give them fanciful names.

Binary stars can be classed in three types, depending on the distance between their components relative to their sizes. A contact binary is a star whose components are so close together that the outermost part of their stellar atmospheres forms a common envelope that surrounds both of them; these may eventually merge to form a single star. With semidetached binaries one component is losing mass to its companion, which may gather it in an accretion disc, and which if it gains enough mass may form a type Ia supernova (see for example, Beta Lyrae, as well as the novel 2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur C. Clarke, below). Detached binaries have components that are more or less distant from each other (up to appreciable fractions of a light-year) and interact only gravitationally, and they may have orbital periods as long as hundreds of thousands of years (for example Proxima Centauri around Alpha Centauri AB)—a fact that adds considerably to the difficulty astronomers encounter in distinguishing true binary stars from mere optical doubles.

Although some planetary orbital configurations are dynamically impossible in binary star systems, and other orbits present serious challenges for potential biospheres because of likely extreme variations in surface temperature during different parts of the orbit (see Helliconia by Brian Aldiss, below; also see The Songs of Distant Earth by Arthur C. Clarke), it has nonetheless been estimated that 50–60% of binary stars are capable of supporting habitable terrestrial planets within stable orbital ranges.[2] Simulations have shown that the presence of a binary companion can actually improve the rate of planet formation within stable orbital zones by "stirring up" the protoplanetary disk, increasing the accretion rate of the protoplanets within (see Starship Troopers directed by Paul Verhoeven, and the Star Trek episode "Singularity", below).[2]

Multiple stars

Artist's impression of the orbits of HD 188753 A-BC, the same triple star system depicted in the graphic above from a moon's surface. This system is hierarchical.

Multiple star systems or physical multiple stars are systems of more than two stars.[3] Various multiple star systems may be called triple if they contain three stars; quadruple if they contain four stars, quintuple for five stars, and so on. These systems are smaller than open star clusters, which have more complex dynamics and typically have from 100 to 1,000 stars.[4]

Many possible configurations of small groups of stars are dynamically unstable, as eventually one star will approach another closely and be ejected from the system.[5] This instability can be avoided if the system is what Evans[6] has called hierarchical (see graphic). In a hierarchical system, the stars in the system can be divided into two smaller tightly bunched groups, each of which traverses a larger orbit around the system's center of mass. Each of these smaller groups may also be hierarchical, and so on. A good example of this is the hierarchical triple star Alpha Centauri AB-C, where the dash in AB-C indicates that AB is one subgroup, and C the other (for another example see Marune: Alastor 993 by Jack Vance, below). This is not to say that more chaotic multiple star systems do not exist: trapezia are young, unstable systems—thought to form in stellar nurseries—that quickly fragment and may eject components as galactic high velocity stars. An example of such a system is the Trapezium in the heart of the Orion nebula.[7][8] (See also "The Devil on Salvation Bluff" and the Durdane trilogy by Jack Vance, below.)

Most multiple star systems known are triple; for higher multiplicities, the number of known systems with a given multiplicity decreases exponentially with multiplicity; this was confirmed with a sample of 807 nearby stars by the astronomer A Tokovinin.[9] A similar exponential relationship holds for 41 multiplicities of real binary and multiple star systems cited in fiction, as listed in the following section.[note 1]

Real binary and multiple stars in fiction

When authors invent new worlds, they may place them in orbits around real stars that shine in the Earth's sky, but they may also invent new suns right along with the planets. Accordingly, this article is about imaginary binary and multiple stars, their planetary systems, and the works of fiction set in them. Still, since between one-third and one-half of the stars actually residing in the neighborhood of the Sun are binaries or multiples,[10][11] it is not surprising to find many of these featured in fiction as well. Works concerning real stars in binary or multiple systems are treated elsewhere, exactly like works about real single stars; for example, Sirius is a real star and a binary star, and its fiction is the subject of the article Sirius in fiction. All such stars have their own articles, for which links are provided below, along with the multiplicities of the stars:

There follow references to imaginary binary and multiple stars depicted as locations in space or the centers of planetary systems, categorized by genre. The items follow the usual convention that planet names are in bold face; for this article, star names are bold orange:

Literature

The writer Jack Vance is an accomplished world-builder who, 60 years ago, provided a model for the planetary romance which has been in significant use by creators of speculative fiction ever since.[12] He is further notable among science fiction authors for his frequent use of binary and multiple star systems in his stories: His worlds spin under multiple suns. His most ambitious works in this vein are the Durdane trilogy and Marune: Alastor 933, each of which is treated in detail below. His numerous less substantial explorations of the theme[13] are described briefly here:

- "The Unspeakable McInch" (1948). Binary system: Sclerotto; the red sun, the blue sun.[14] Magnus Ridolph tracks down an enigmatic criminal mastermind.

- "To B or Not to C or to D" (1950). Triple system: Jexieka; red giant Rouge, white Sol-like Blanche, dark companion Noir.[15] Magnus Ridolph investigates a mysterious case of vanished agricultural workers.

- "The Devil on Salvation Bluff" (1955). Wildly chaotic quadruple system: Glory; Red Robundus, small yellow-green Urban, silver dwarf Maude, green cat’s-eye Faro.[16] Uptight colonists learn to go with the flow of kaleidoscopic random episodes of daylight and dark.

- "The Gift of Gab" (1955). Binary system: Sabria; dull red giant Geideon, blue-green Atreus.[17] The superintendent of a pelagic mining operation abruptly disappears.

- The Star King (1964). Binary system: red dwarf star, habitable dead star.[18] Kirth Gersen seeks out a criminal’s secret hideaway on a dead star.

- The Green Pearl (1985). Binary system: Tanjecterly; green sun, lemon-yellow sun.[19] Aillas searches for princess Glyneth, abducted to the world Tanjecterly.

- "The Stark" (outline for an unpublished work). Binary system: uninhabitable planets; red and blue binary.[20] A star ark bearing the remnants of humanity ranges the galaxy seeking a home.

- "Nightfall" (1941) short story written by Isaac Asimov, probably the single most famous US science fiction story of all time,[21] published in Astounding Science Fiction and expanded as the novel Nightfall with Robert Silverberg in 1990. The planet Lagash (Kalgash in the novel) resides in a sextuple star system, whose six suns—great golden Onos, red dwarf Dovim, actinic white dwarfs Trey and Patru, and blue-white Tano and Sitha[note 2]—combine to provide eternal daylight, save once every 2049 years, when an eclipse plunges the planet into prolonged darkness (compare Marune: Alastor 933 by Jack Vance and the film Pitch Black with Vin Diesel, below). Scientists, foreseeing the hiatus, prepare their countrymen to endure a lightless season, but when night does fall the populace is driven mad by the unimagined sight of the myriad stars, and civilization collapses in chaos: ... [he] turned his eyes toward the bloodcurdling blackness of the sky. / Through it shone the Stars! / There were thousands of them, blazing with incredible power ... a dazzling shield of terrifying light that filled the entire heavens / Their icy monstrous light was like a million great gongs going off at once.[24] The Kalgash system is of type A-BC—D-EF: Kalgash's primary Onos orbits in binary with the close pair Trey and Patru, and this triplet orbits in binary at a higher hierarchical level with the remaining triplet comprising Dovim and Tano-Sitha.

- "Legends of Smith's Burst" (1959) - short story written by Brian Aldiss and published in Nebula Science Fiction.[25] Jami Lancelo Lowther, interstellar picaresque adventurer, finds himself sold in slavery to the alien chimera Thrash Pondo-Pons on the planet Glumpalt, deep in the Hybrid Cluster of Smith's Burst. Thrash, leading his new acquisition home, dispatches him up a tall tree to spy out landmarks. From the highest branches Lowther, feigning bewildered panic, cries out "Master, do not gallop off and leave me here alone!" Clambering back to the ground, and dissembling vast relief, he relates the wonderful illusion produced by the magical tree. When his master climbs up to see for himself, Lowther steals his steed and makes good his escape; this is just the first of his many tricks and adventures under the four suns of Glumpalt: a monstrous pink thing, like a blob of custard; a more powerful yellow globe; a blazing white sun; and at last the black sun, an antimatter star that appears as "a great sooty ball, crammed with darkness, radiating blackness."[26] The antilight emitted by the black sun cancels the ordinary light of the other three suns, and plunges the world into darkness.[note 3]

- Solaris (1961), Polish language novel by Stanisław Lem, translated into French, then English in 1970.[note 4] Earth scientists seeking to understand a nonhuman intelligence that is manifested by the world ocean of the planet Solaris achieve few insights, while the alien consciousness toys with their psyches with discomfiting results. The sentient sea flexes and ripples under the inconstant light of a pair of suns: In the warm glow of the red sun, mists overhung a black ocean with blood-red reflections, and waves, clouds, and sky were almost constantly veiled in a crimson haze. Now, the blue sun pierced the [scientists' observatory] with a crystalline light.[28] Like much of Lem's work in his "golden" period from 1956–1968, this work uses the mystery of a strange locality—in this case a watery planet heaving under the strange light of a red-blue binary system—to educate its protagonists into understanding the strengths and limitations of humanity.[29]

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), novelization by Arthur C. Clarke of his script for the motion picture. In this well-known tale, a crystalline monolith sent by an alien race precipitates the dawning of intelligence among a group of hominid ancestors of human beings. Millions of years later, Dr. David Bowman finds himself on a mission to the Saturn system (along with the dicey computer HAL), where he discovers a much larger monolith that serves him as a star gate (it's full of stars!); it conducts him to the vicinity of a huge red giant no hotter than a glowing coal. Here and there, set into the somber red, were rivers of bright yellow—incandescent Amazons ... a second semidetached star, a mere point of blue-white radiance ... was moving at unbelievable speed across the face of the great sun ... immediately below it, drawn upwards by its gravitational pull, was a column of flame thousands of miles high ...[30] In this immense setting an advanced alien technology transforms him into a new immortal entity, a Star Child, that can live and travel in space: In an empty room, floating amid the fires of a double star twenty thousand light-years from Earth, a baby opened its eyes and began to cry.[31] This image, in both the novel and the screenplay for the film, shows an unhappy mankind crying out for a lost father ... the closest thing science fiction has yet produced to [expressing] the longing for God.[32]

- Nova (1968), novel written by Samuel R. Delany. Earth and the Pleiades Federation vie for influence in the Outer Colonies where mines produce trace amounts of the prized power source Illyrion. Lorq Von Ray, a scarred and obsessed captain from the Pleiades, recruits a motley crew of misfits to help him achieve political and economic dominance by securing a vastly greater amount of Illyrion—seven ton's worth—directly from the heart of a stellar nova. Two of his crew are the twins black Idas and albino Lynceos, hailing from Argos on the Colony world Tubman B-12 where they grew up "under three suns and a red moon."[33]

- Durdane trilogy (1971-1973), series of novels (The Anome, The Brave Free Men, The Asutra) by Jack Vance. The world Durdane, inhabited by a quaint people with a rich tradition of music together with a pervasive preoccupation with color symbology—and ruled by the eponymous, anonymous Anome—is infiltrated by alien incubi (the Asutra) in a manner reminiscent of the Slugs in Heinlein's classic novel The Puppet Masters. Durdane threads a chaotic triple system of stars: The suns climbed the sky, the blaze of white Sassetta passing across the plum-red haunch of Ezeletta [from the second book on, this is shortened to Etta, and the colors change],[34] blue Zael on the roundabout: three dwarf stars dancing through space like fireflies ... The suns tumbled up into the mauve autumn sky like rollicking kittens: Sassetta over Ezeletta behind Zael [35] ... Etta swung up near the horizon, producing a false blue dawn, then pink Sassetta slanted sidewise into the sky, then white Zael, and again blue Etta.[36]

- Marune: Alastor 933 (1975), novel written by Jack Vance. Marune is a planet in the Alastor Cluster, located in a quadruple star system, and home to the Rhunes, a peculiar, exacting people who inhabit their castles high up in the windy crags. The novel relates the tale of a young, amnesiac Rhunish duke and his struggles to regain his memory, his duchy, and his castle Benbuphar Strang. As important as the story is the setting: Marune orbits the orange dwarf Furad (●), which in turn orbits blue Osmo (●). Red Maddar (●) and green Circe (●) circle each other, and the pair form a hierarchical binary system of type AB-CD with Furad-Osmo, no two orbits being coplanar. The suns thus combine in the sky to produce a wonderful variety of illuminations, ... during which the character of the landscape changes profoundly. The population is naturally affected, and most especially the Rhunes[note 5] ... About once a month, the land grows dark, and the Rhunes grow restless. —this is Mirk, when awful deeds transpire.[37] The following gallery illustrates the different modes of Marune daylight, and shows which stars combine to produce them.

| The castle Benbuphar Strang of Sharrode under different phases of illumination |

|---|

|

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979), novel by Douglas Adams. Magrathea is an ancient planet located in orbit around the twin suns Soulianis and Rahm in the heart of the Horsehead Nebula (see graphic). Magrathea is a world whose economy was based on the manufacturing of bespoke planets for the wealthiest people in the universe, back in the days of the Galactic Empire (it was Magrathea that created the Earth). On Magrathea, hapless Arthur Dent is trying to convince depressed robot Marvin that the planet's double sunset is indeed worthy of admiration: But that sunset! I've never seen anything like it in my wildest dreams...the two suns! It was like mountains of fire boiling into space...We only ever had the one Sun at home.[38]

- The Snow Queen (1980), novel by Joan D. Vinge.The Snow Queen takes place on a mostly oceanic planet called Tiamat, whose suns orbit a black hole, which facilitates a type of interstellar travel and connects Tiamat to the rest of the civilized galaxy (the "Hegemony", the remnants of a fallen Galactic Empire).[39]

- Helliconia (1982-1985), trilogy of novels (Spring, Summer, and Winter) by Brian Aldiss. Terrestrial humanity covertly observes, from their space station Avernus, the changing fortunes of the Helliconian "humans" and their rivals the bovine-descended phagors during the course of a Helliconian Great Year (~2500 Earth years). Helliconia lies in a binary star system consisting of the yellow-orange dwarf Batalix (its primary), which orbits in turn the white supergiant star Freyr in the constellation of Ophiuchus about a thousand light-years from the Sun. Aldiss explores in detail the astronomy, geology, climatology, geobiology, microbiology, religion, and society of a planet whose Great Year derives not from an inclined axis of rotation, but from the evolving geometry of the binary system. The Phagors call the 'Humans' the Sons of Freyr, and recall in folk memory a time before Batalix entered orbit - before the 'Humans' evolved intelligence and became dominant during the warm periods. "As an exercise in world-building, the Helliconia books lie unassailably at the heart of modern science fiction ..."[40]

- Expedition (1990), science fiction book written and illustrated by Wayne Barlowe. The year is 2366 and Earth, with the help of the technologically advanced Yma race, is embarking on an arduous repair of the effects of centuries of relentless environmental degradation. The book concerns the recent human eco-expedition to a binary star system approximately 6.5 light-years from Earth and its planet Darwin IV, home to a congeries of bizarre and utterly alien life forms. Barlowe writes as a sort of 24th century Audubon, presenting his findings in a collection of paintings, sketches, field notes, and diary entries that limn his explorations of this exotic world.

- Honor Harrington (1993- ), series of novels written by David Weber. The binary star system Manticore has three habitable planets and (importantly) one wormhole junction. The primary component Manticore A has two gentle habitable planets, Manticore (Manticore A III) and Sphinx. The secondary component Manticore B has one harsh habitable planet, Gryphon, home of rigorous conservatives and royalists. The star system is the capital system of the Star Empire of Manticore, whose Royal Manticoran Navy is the setting for protagonist Honor Harrington's Horatio Hornblower-like military career.

- Star Carrier: Earth Strike (2010), novel written by Ian Douglas. Eta Boötis is a binary system (as is suspected in real life[41]) consisting of a type GO IV star with a white dwarf orbiting 1.4 AU distant. The system also contains fourteen planets, of which Eta Boötis IV, local name Al Haris al Sama, contains a colony of Muslim expatriates from Earth.[42] This colony is attacked and destroyed by aliens named the Turusch during the course of the novel.

- Cycle of Fire (Hal Clement, 1957). Abyormen is a planet in a binary system where the two components' orbits are highly eccentric. This produces striking temperature extremes and two seasons, a hot season and a cold season. Living forms that exist during one season die out at the onset of the other and at the same give birth to living things that exist during the other season. A small number of rational individuals shelter themselves in isolated locations that allow them to live during the "other" season. They consider their fate not as a chance to live but as a burden and a duty they must take in order to pass knowledge through generations and preserve civilization.[43]

Film and television

- "Pyramids of Mars" (1975) et alii, serial written by Robert Holmes and Lewis Greifer, and directed by Paddy Russell for the long-running British science fiction television series Doctor Who. This episode contains the first reference to Gallifrey, the home world of Doctor Who, the last of the Time Lords, which orbits a tightly bound binary star system of two yellow-white stars—one similar to the Sun and the other a white dwarf (see graphic: The double system is somewhat obscured by the citadel itself, but can be seen as refracted pairs of highlights on the spherical surface of the fastness' defensive force field). Gallifrey is quite remote from the Earth: In the 1996 television movie Doctor Who, the Doctor shows his two human associates Chang Lee and Grace Holloway a view of the universe: [DW] Look over there ... That's home. / [GH] Gallifrey! / [DW] 250 million light years away. / [GH] Whoo.[44] This would place it far outside our own galaxy, which is about a hundred thousand light years in diameter, and indeed outside the Local Group and even the Virgo Supercluster; however, at this distance it would still be within the Pisces-Cetus Supercluster Complex.[45]

- Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977), film written and directed by George Lucas, as part of the six-installment Star Wars saga of feature films. The planet Tatooine is the setting for many key events in the Star Wars series, appearing in every franchise film except The Empire Strikes Back and Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Since it is the home world of both Anakin and Luke Skywalker, it holds great importance in the Star Wars universe. Tatooine's G-type twin suns (Tatoo I and Tatoo II—see graphic below) overheat its surface, making water and shade hard to come by. The planet's indigenous lifeforms are well-adapted to its arid climate, but human settlers often become moisture farmers and live in subterranean dwellings to survive.

- The Dark Crystal (1982), animatronic film written by Jim Henson and David Odell, and directed by muppeteer Henson and Frank Oz. On another world, in another time (a thousand years gone) the evil Skeksis rule a dwindling, ruined planet, while the gentle wizardly Mystics raise Jen, the last—but for one other—of the Gelflings. The world Thra was once green and bountiful, spinning in a triple star system ruled by the blue dwarf Dying Sun,[note 6] the red Rose Sun, and the white giant Great Sun,[47] until the Crystal of Truth shattered and in so doing loosed strife and destruction on the land. The elfin Gelfling boy, taken in by the Mystics after his clan was killed, is told by his Mystic master that he must find and restore the crystal shard. If he fails to do so before the Great Conjunction of the three suns (see graphic below), the Skeksis will rule forever: When single shines the triple sun / What was sundered and undone / Shall be whole, the two made one / By gelfling hand or else by none.[48] Thus begins Jen's quest.[note 7]

The Great Conjunction is just seconds away in the sky over Thra, from The Dark Crystal.

- "Night Terrors" (1991), episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation written by Pamela Douglas and Jeri Taylor, and directed by Les Landau as part of the film, television, and print franchise originated by Gene Roddenberry. Searching for a disabled scientific expedition in the vicinity of a binary star, the USS Enterprise becomes ensnared in a topological singularity—the same Tyken's Rift that has trapped the earlier vessel. The only way to escape is to detonate a huge explosion, but how? ...Meanwhile the human members of the crew begin to suffer an induced mass psychosis thanks to a mysterious influence that is keeping them from dreaming. Only half-betazoid Troi can still dream, and she dreams of the double sun (see graphic above) —no wait, it's a hydrogen atom, with one electron orbiting one proton!—a telepathic cry for help being broadcast by a likewise trapped alien race, with dream deprivation an unintended consequence. When Troi realizes their need, the Enterprise releases a flood of hydrogen gas into the Rift, which the aliens engineer into a great blast, and everyone wins free.

- Alien3 (1992), film written by Vincent Ward et al. and directed (and subsequently disavowed) by David Fincher. Series heroine Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) together with several crewmates (and also, unknown to them, one alien) eject from a disabled spaceship and crash-land on Fiona 161, a penal foundry facility orbiting in a binary star system. The prison world, nicknamed "Fury," houses a population of male inmates with histories of physical and sexual violence. Mayhem ensues.

- Starship Troopers (1997), film written by Edward Neumeier and directed by Paul Verhoeven, based on the military themed 1959 novel by Robert Heinlein, a work replete with allusions to World War II and to Japanese tactics in the Pacific war.[49] Porteño high schooler John Rico and his friends resolve to enlist in the military to earn their Federation citizenship. Boot camp goes poorly however, and Rico is contemplating resigning from the force when the arachnid Bugs, archrivals of humanity, launch a meteor bombardment from their system that destroys his home town, Buenos Aires. The Pearl-Harborlike attack, the Federation's Doolittle-esque counterstrike against the Bugs' capital planet Klendathu, and the subsequent planet-by-planet naval campaign provide the means for Rico to redeem himself, perform multiple acts of heroism, and get the girl. The picture begins with a "newscast" on the FEDERATION NETWORK, a sly send-up of the government's crude propaganda machine:[note 8] Klendathu, source of the bug meteor attacks, orbits a twin star system where brutal gravitational forces produce an unlimited supply of meteorites (sic)[note 9] in the form of this asteroid belt. [Video shows an asteroid belt full of potential projectiles and the twin suns, one yellow, one white.] To ensure the safety of our Solar System, Klendathu must be eliminated.

- "My Three Suns" (1999), episode of the animated situation comedy Futurama written by J. Stewart Burns and directed by Jeffrey Lynch and Kevin O'Brien (created by Matt Groening). Philip Fry, delivery boy for Planet Express, is assigned the task of conveying a royal consignment across the desert of Trisol[note 10] under the blazing heat of the planet's three suns. Arriving at the Trisolian palace, he is so thirsty that he drinks a beaker of liquid that he finds sitting on the throne. All too late he discovers that the Trisolians are liquid-based life forms, and that he has consumed their emperor. The Trisolians are not happy.

- Pitch Black (2000), film written by Jim and Ken Wheat, and directed by David Twohy. A space transport crash-lands on a desert planet illuminated by three suns: yellow, white, and blue, which bathe it in constant daylight; the colors cast by the triple suns are effectively represented with tinted camera work by cinematographer David Eggby. The light is extinguished in a month-long eclipse that recurs every 22 years—and, coincidentally, shortly after the castaways' planetfall—when flapping swarms of ravenous creatures emerge into the pitch dark to feed. The shipwreck survivors comprise the usual assortment of conflicted and conflicting characters, including Vin Diesel as the tough thug with a well-hidden heart of gold, who manages to bring at least a few of the others unscathed through the harrowing night.[note 11]

- "Singularity" (2002), episode of Star Trek: Enterprise written by Chris Black and directed by Patrick Norris as part of the film, television, and print franchise originated by Gene Roddenberry. The USS Enterprise is exploring a triple star system,[note 12] one of whose components is a Class IV black hole that emits a peculiar type of radiation: It causes the human members of the crew to concentrate so obsessively on certain trivial tasks that they can no longer effectively control the starship. Vulcan science officer T'Pol is unaffected; with faltering assistance from the semiconscious Captain Archer, she must navigate the vessel through a chaotic debris belt orbiting closely around the hole to a sheltered eddy of space time. Here the singularity's influence does not extend and the crew is able to recover.

- Simoun (2006), anime television series written by Hayase Hashiba and directed by Junji Nishimura. Simoun takes place on the planet Daikūriku, an Earthlike planet in a binary star system[note 13] populated by a humanoid race that are all born female and develop as girls until age 17, when they choose a permanent sex. At some point in this world's past, a more technologically advanced culture flourished, but it has since crumbled, and much of its technology has been lost.

- "The Captain's Hand" (2006), episode of Battlestar Galactica written by Jeff Vlaming and directed by Sergio Mimica-Gezzan. Two Raptors go missing during a training mission near a binary star that causes DRADIS (space radar) and communications interference. Shortly after contact with the Raptors is lost, new Pegasus commander Barry Garner challenges Admiral Adama's orders by sending his battlestar directly into the rescue zone—and a trap.

Games

The planet Twinsun, suspended between two stars, with a freezing cold belt of permanent twilight around its equator.

- Star Fox (1993), video game series published by Nintendo. The games follow an independent mercenary unit called Star Fox (made up of anthropomorphic animals) and their adventures around the Lylat planetary system. The system is binary, with two suns: a hot white star, and the cooler red dwarf Solar.

- Little Big Adventure (1994), computer game developed by Adeline Software International and published by Electronic Arts/Activision. The game is set on the planet Twinsun, which inhabits a binary star system in a way quite unusual in science fiction: It is balanced at the center of mass of a pair of mutually orbiting suns, suspended midway between them. Its axis of rotation passes through these pole stars, so that its equator is a freezing cold belt of permanent twilight while the rest of the surface enjoys perpetual daylight (see graphic). The peoples of Twinsun have been sequestered in the Southern hemisphere (foreground of graphic)—effectively imprisoned there by the impassable frigid zone—on the orders of a brutal tyrant called Dr. Funfrock, who has subjugated the planet by developing an army of clones that can instantaneously travel anywhere using teleport machines. The player character is a young humanoid named Twinsen, who must solve riddles and defeat enemies until he finally fulfills the Prophecy, vanquishes Funfrock, and rescues his girlfriend Zoe.[note 14]

- Unreal (1998), computer game with groundbreaking and influential graphics technologies by programmer Tim Sweeney,[51] designed by James Schmalz and Cliff Bleszinski, and published by GT Interactive. The player assumes the role of Prisoner 849, marooned by the crash of a prison spaceship on the planet Na Pali in a binary star system. The reptilian Skaarj kill most of the shipwrecked crew but 849 escapes, befriends the native humanoid Nali (slaves to the Skaarj), teleports to the labyrinthine Skaarj mother ship, and kills the Skaarj queen.

- Perfect Dark (2000), Nintendo 64 game developed by Rare Ltd. which features as its chief antagonists the Skedar, an alien race who originate from a desert planet with three suns.

- Rayman 2: The Great Escape (1999-2000), video game in the series developed and published by Ubisoft. An evil army of Robot-Pirates has taken over the Glade of Dreams. "Glade" is in a binary system with two yellow suns, one large and one small, that appear in various game backgrounds. Rayman must defeat the forces of evil, and defeat the Admiral Razorbeard on his Buccaneer.

See also

Binary and multiple stars are frequently referred to as locations in space or the centers of planetary systems in fiction. For a list containing many real solitary, binary, and multiple stars and their planetary systems that appear in fiction, see Stars and planetary systems in fiction.

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The frequencies for 41 real binary and multiple star systems in fiction are: binary stars → 28; triple stars → 8; quadruple stars → 3; quintuple stars → 1; and sextuple stars → 1. The frequency f in terms of the multiplicity m is well approximated for this set of data points by the exponential function f ≈ 250e—1.12m, obtained by a linear regression on ln f against m, with Pearson's r ≈ - 0.97, indicating a strong correlation of 97%.

- ↑ In the novel Nightfall, the six suns of Kalgash in the order of their appearance in the narrative are named Onos, Dovim, Trey, Patru, Tano, and Sitha.[22] The cardinal numbers 1 - 6 in the Romanian language are unu, doi, trei, patru, cinci, and şase. In the original short story the six stars are named using Greek letter names: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta with the remaining not mentioned.[23]

- ↑ While it is far from rare in science fiction for unusual astronomical events to cast the otherwise eternally lit planets of multiple stars into unwonted darkness (see "Nightfall" by Isaac Asimov, Marune: Alastor 933 by Jack Vance, and the film Pitch Black in the article above for examples), Brian Aldiss is the only author to imagine an active agent—the black sun—rather than a chance orbital configuration as the harbinger of the night, as if, in the words of Latvian writer Anita Vanaga, "darkness [is] an inpenetrable multitude that blots out the light."[27]

- ↑ The 1970 translation was followed a year later by a Russian language motion picture directed by Andrey Tarkovskiy, and in 2002 by an English language picture written and directed by Steven Soderbergh.

- ↑ Behavior considered proper during one mode may be considered absurd or in poor taste during another. The following list displays several diurnal modes, with color swatches showing the associated quality of daylight, and examples of appropriate conduct for the mode:[37]

• Isp (swatch): A phase befitting the consummation of formal ceremonies

• Aud (swatch): A time for going forth to battle, conducting litigation, fighting a duel, collecting rent

• Umber (swatch): Persons advance their erudition and hone their special skills

• Green Rowan (swatch): A mode conducive to poetry and sentimental musing

• Red Rowan (swatch): A relaxed time, when a man may take a glass of wine in company with other men

• Chill Isp (swatch): Inspires the Rhune with a thrilling ascetic exultation; he plans great deeds and forms gallant resolves

• Mirk (swatch): When the light fails, dark deeds are done—signally including procreation through real or simulated rape - ↑ Blue dwarfs can be called "dying suns" in the sense that they are theoretical late stages in the evolution of red dwarfs toward their end-state senescence as white dwarfs. Red dwarfs are very long-lived; the universe is not yet old enough for blue dwarfs to exist.[46]

- ↑ The Dark Crystal is unique among the works listed in this article in that the syzygy of the system's astronomical bodies is a conjunction that multiplies the suns' power, rather than an eclipse that drains the world of their light and plunges it into perilous darkness.

- ↑ Director Verhoeven stated that the film's satirical use of irony and hyperbole is "playing with fascism or fascist imagery to point out certain aspects of American society... of course, the movie is about 'Let's all go to war and let's all die.'"[50]

- ↑ Meteoroids drift in space; meteors blaze in the sky; meteorites repose on the ground. The proper term here would be meteoroids.

- ↑ Tri-sol = three suns.

- ↑ Pitch Black (every 22 years) and two of the novels described above—Nightfall (every 2049 years) by Isaac Asimov and Robert Silverberg, and Marune: Alastor 933 (Mirk every 30 days) by Jack Vance—all feature planets basking in the near perpetual daylight provided by their multiple star systems. On each, the eventual coming of the dark portends a dreadful nightmare, and the rarer the fall of night, the more terrible the demons it unleashes.

- ↑ A real triple star system that figures importantly in the Star Trek universe is 40 Eridani: The planet Vulcan orbits 40 Eridani A.

- ↑ In exterior scenes, two suns are visible in the sky of Daikūriku.

- ↑

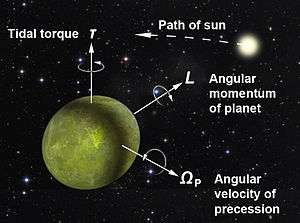

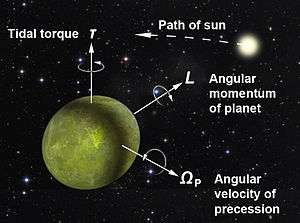

Vectors relating tidal torque to Twinsun's rotation and precession. The axial distortion of the planet is exaggerated.

References

- ↑ Heintz, W D (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht, NL: D Reidel Publishing Company. pp. 1–2. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- 1 2 Quintana, Elisa V; Lissauer, Jack J. "Terrestrial Planet Formation in Binary Star Systems". arXiv:0705.3444

[astro-ph].

[astro-ph]. - ↑ Percy, John R (2007). Understanding Variable Stars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-521-23253-8.

- ↑ Binney, James; Tremaine, Scott (1987). Galactic Dynamics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-691-08445-9.

- ↑ Leonard, J T (2001). Paul Murdin, ed. The Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Article: "Multiple Stellar Systems: Types and Stability". Philadelphia: Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-750-30440-5.

- ↑ Evans, David S (December 1968). "Stars of Higher Multiplicity". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 9: 388–400. Bibcode:1968QJRAS...9..388E.

- ↑ Heintz, W D (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht, NL: D Reidel Publishing Company. pp. 67–68. ISBN 90-277-0885-1.

- ↑ Allen, Christine; Poveda, Arcadio; Hernández-Alcántara, Alejandro (2006). "Runaway Stars, Trapezia, and Subtrapezia". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica (Serie de Conferencias). 25: 13–15. Bibcode:2006RMxAC..25...13A.

- ↑ Tokovinin, A. "Statistics of Multiple Stars: Some Clues to Formation Mechanisms". International Astronomical Union. pp. 84–92. Retrieved 2012-07-20.

- ↑ "Most Milky Way Stars Are Single". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ↑ Mukai, Koji. "Imagine the Universe! | Ask an Astrophysicist". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Vance, Jack". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 1265. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ "The Vance Vocabulary Search Tool". TOTALITY. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). "The Unspeakable McInch". Gadget Stories. 3. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 91. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). "To B or Not to C or to D". Gadget Stories. 3. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 212. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). "The Devil on Salvation Bluff". The World Thinker and Other Stories. 2. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. pp. 280; 282, 283, 285, 295. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). "The Gift of Gab". The Houses of Iszm and Other Stories. 8. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 121. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). The Star King. 22. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 158. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). The Green Pearl. 37. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 424. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). "The Stark". Wild Thyme and Violets, Other Unpublished Works, and Addenda. 44. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 85. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Asimov, Isaac". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 56. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac; Silverberg, Robert (1990). Nightfall. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0-553-29099-1.

- ↑ "Translate". Google. Translate one, two, three, four, five, six. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac; Silverberg, Robert (1990). Nightfall. New York: Bantam Books. p. 200. ISBN 0-553-29099-1.

- ↑ Aldiss, Brian. "Legends of Smith's Burst". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- ↑ Aldiss, Brian (1959). "Sector Yellow". Starswarm. New York: New American Library Signet. pp. 100; 112; 117.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (2012). "The Universe Unseen, On Display in Chelsea". The New York Times. CLXII (55,905): D3.

- ↑ Lem, Stanisław (1970). Solaris. trans Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox. San Diego, CA: Harcourt. p. 27. ISBN 0-15-602760-7.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Lem, Stanisław". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 711. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C (2000). 2001: A Space Odyssey. New York: Roc Books. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-451-45799-4.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C (2000). 2001: A Space Odyssey. New York: Roc Books. p. 291. ISBN 0-451-45799-4.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Clarke, Arthur C". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 230. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Delany, Samuel R (1968). Nova. New York: Bantam Books. p. 30.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). Durdane: The Brave Free Men. 27. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 262. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). Durdane: The Anome. 27. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. pp. 20; 179. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). Durdane: The Asutra. 27. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 455. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- 1 2 Vance, Jack (2005). Marune: Alastor 933. 30. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Adams, Douglas (2002). The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Del Rey Books. p. 100. ISBN 0-345-45374-3.

- ↑ Aragona, Mark. "Book Review: The Snow Queen by Joan D. Vinge". Digital Science Fiction. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Aldiss, Brian W". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 12. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ van Belle, Gerard T.; Ciardi, David R.; Boden, Andrew F. (March 2007), "Measurement of the Surface Gravity of η Bootis", The Astrophysical Journal, 657 (2): 1058–1063, arXiv:astro-ph/0701120

, Bibcode:2007ApJ...657.1058V, doi:10.1086/510830

, Bibcode:2007ApJ...657.1058V, doi:10.1086/510830 - ↑ Douglas, Ian (2010). Star Carrier Book One: Earth Strike. New York: Harper Voyager. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780061840258.

- ↑ Clement, Hal (1957). Cycle of Fire. ISBN 0-345-24368-4.

- ↑ "Memorable quotes for Doctor Who". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Tully, R B (1986-04-01). "Alignment of clusters and galaxies on scales up to 0.1 C". The Astrophysical Journal. 303: 25–38. Bibcode:1986ApJ...303...25T. doi:10.1086/164049. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Adams, F C; Bodenheimer, P; Laughlin, G (2005). "M dwarfs: planet formation and long term evolution". Astronomische Nachrichten. 326 (10): 913–919. Bibcode:2005AN....326..913A. doi:10.1002/asna.200510440. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Froud, Brian. The World of the Dark Crystal. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 3. ISBN 0-810-94579-7.

- ↑ "Memorable Quotes for The Dark Crystal". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2012-08-07. f>

- ↑ Lacey, Liam (2002-04-12). "Starship Troopers". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Tobias, Scott (2007-04-03). "Interview: Paul Verhoeven". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- ↑ Shamma, Tahsin. "Unreal Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

Vectors relating tidal torque to Twinsun's rotation and precession. The axial distortion of the planet is exaggerated.

Vectors relating tidal torque to Twinsun's rotation and precession. The axial distortion of the planet is exaggerated. [astro-ph].

[astro-ph]. , Bibcode:2007ApJ...657.1058V, doi:10.1086/510830

, Bibcode:2007ApJ...657.1058V, doi:10.1086/510830