Black holes in fiction

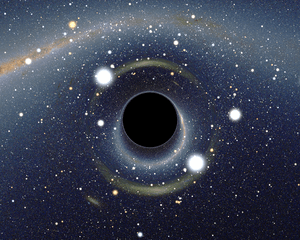

The study of black holes, gravitational sources so massive that even light cannot escape from them, goes back to the late 18th century. Major advances in understanding were made throughout the first half of the 20th century, with contributions from many prominent mathematical physicists, though the term black hole was only coined in 1964. With the development of general relativity other properties related to these entities came to be understood, and their features have been included in many notable works of fiction.[1]

Literature

Early works

- The Sword of Rhiannon (1950): a novel written by Leigh Brackett, originally published as "The Sea-Kings of Mars" in Thrilling Wonder Stories (June 1949). Greed entices the archaeologist looter Matt Carse into a forgotten tomb of the old Martian god Rhiannon. There a strange singularity plunges the unlikely hero into the Red Planet's fantastic past, when vast oceans covered the land and the legendary Sea-Kings ruled from terraced palaces of decadence and delight. The tomb encloses a bubble of darkness ... [like] those lank black spots far out in the galaxy which some scientists have dreamed are holes in the continuum itself, windows into the infinite outside our universe! [2] Rhiannon is regarded as the best of Brackett's sword and planet works set in the neo-Burroughsian Martian past on the other side of the black hole, a bygone time representing the last gasp of a decadence endlessly nostalgic for the even more remote past.[3]

- Stowaway to the Mushroom Planet (1956): a juvenile science fiction novel written by Eleanor Cameron. Two boys experience adventures and strange encounters on and around the Mushroom Planet, a tiny moon in an invisible orbit around the Earth that is only visible using the special filter provided by a mysterious Mr. Bass.[4] One of the hazards of the journey there is a "hole in space," rendered visible by a swarm of meteors that orbits it in a funnel-shaped circle and falls into it to completely vanish from sight. In the hole, ...there's no time—that is, for [the infalling space traveler] Horatio there's no time. It's all just one big long NOW. As he fell into the hole, Horatio felt as though I were being wrenched bone from bone ... That must be when he went through the hole in space.[5]

- The City and the Stars (1956): the debut novel (originally published as Against the Fall of Night) of Arthur C. Clarke, with the reworked (City) version being widely considered his most memorable work and one of the strongest tales of conceptual breakthrough in genre science fiction.[6] A once glorious galactic Empire was nearly destroyed by its greatest creation gone awry, a pure disembodied intelligence—now called the Mad Mind. The Mad Mind could not be destroyed, for it was immortal. It was driven to the edge of the Galaxy and there imprisoned in a way we do not understand. Its prison was a strange artificial star known as the Black Sun, and there it remains to this day.[7] The Black Sun is often interpreted as a black hole—an identification made explicit in Gregory Benford's sequel Beyond the Fall of Night (1990, see below).[note 1]

- "At the Core" (1966): a short story by Larry Niven published in Galaxy Science Fiction magazine. Spaceship pilot Beowulf Schaeffer is to take an experimental and extremely fast Puppeteer ship, the Long Shot, through a deadly thronging wilderness of stars to the galactic core (compare "Dead Ahead" by Jack Vance). The center of the galaxy is exploding in a chain reaction of supernovas (a proposed precursor to the formation of a supermassive black hole there[8]): The patch kept expanding as I went in ... a great bright amoeba reaching twisting tentacles of fusion fire deep into the vitals of the Core.[9]

- "Kyrie" (1968): a short story written by Poul Anderson. An expedition exploring a fresh supernova remnant emerges from jump to face an electromagnetic nebular storm as it draws close to the cataclysm's residual black hole (Anderson mentions its Schwartzschild radius, but uses the terms "supernova core" and "star's exposed heart" to refer to the hole itself[10]); their ship faces imminent destruction by an immense crackling globe of ionized gas that is on course to collide with it. Rescue is effected by Lucifer, a plasma-based being allied to the ship, who can communicate instantaneously over unlimited distances with the ship's onboard telepath. Exhausted by the effort of fending off the deadly hazard, Lucifer finally tumbles into the black hole, his death agonies stretched to forever in her mind as his entanglement in the hole's gravitational field slows his clock asymtotically to zero at the event horizon. She will never stop hearing his screams, and there is no place in the universe where she will find peace.[note 2]

- Creatures of Light and Darkness (1969): a novel written by Roger Zelazny. In this novel of science fiction and ancient Egyptian folklore, recognized for its complex plot, mythic resonance, and fluent verbal intensity,[11] the god Thoth has ruled the Universe, but lost his supremacy to his rebellious angels; now he must dedicate all his remaining powers toward containing and—perhaps—defeating the archenemy, the Thing That Cries In The Night. One casualty of the battle is Thoth's brother Typhon, who contains within himself the black hole-like Skagganauk Abyss: sometimes called the chasm in the sky, the place where it is said that all things stop and nothing exits … empty of space, also. It is a bottomless hole that is not a hole, It is a gap in the fabric of space itself … It is the big exit leading nowhere, under, over, beyond, out of it all.[12]

Golden Age

In 1958, David Finkelstein identified the Schwarzschild surface of a black hole as an event horizon, extending the commonplace notion that objects beyond the Earth's horizon cannot be seen, calling it "a perfect unidirectional membrane: causal influences can cross it in only one direction."[13] This result helped usher in the golden age of general relativity, which was marked by general relativity and black holes becoming mainstream subjects of research. Science fiction stories written before this date (see Early works above) often portray one or two features of black holes accurately, but display a naive view of them overall. Later tales (below) tend to portray black holes in a fashion more thoroughly in accord with modern understanding, with the term black hole itself being introduced by John Wheeler in 1969 and adopted immediately and enthusiastically by science fiction writers.[14] In science fiction stories written up to this date (Early works), black holes are called by a variety of more or less suggestive names, including "black" and "hole" used in isolation; after 1969, almost all works use Wheeler's combined term "black hole."

In the stories that follow, a common plot device is that of the escaped black hole that oscillates back and forth through the core of an astronomical body and, most often, eventually consumes it: Mars in "The Hole Man" by Larry Niven (1973), an asteroid in "The Borderland of Sol" by Niven (1975), the Earth in Hyperion by Dan Simmons (1989), Earth by David Brin (1990) and The Krone Experiment by J. Craig Wheeler (1986), the Moon in "How We Lost the Moon, a True Story by Frank W. Allen" by Paul J. McAuley (1999), and the Earth once more in Olympos by Simmons (2005). Surprisingly, given the widely publicized 1975 publication by Stephen Hawking of the theory of quantum evaporation, few of the works incorporate this idea (notably Earth by David Brin (1990) and Olympos by Dan Simmons (2005)). While the rapid evaporation of the smallest quantum black holes does not rule out such a catastrophe, other physical aspects of the collapse scenario remain problematic.[note 3]

On the other hand, the allied notion of deploying quantum black holes that are so small as to be maneuverable for use as offensive weapons in crime or warfare (see "The Borderland of Sol" by Larry Niven (1975) and Chaos and Order: The Gap Into Madness (1994) by Stephen R. Donaldson) is dealt a real blow by their presumably brief lifetimes.

- "He Fell into a Dark Hole" (1973): a short story by Jerry Pournelle originally published in Analog science fiction magazine. Ships are mysteriously disappearing on the direct "Alderson" (hyperspace) path from the planet Meiji in the 82 Eridani system to the Earth.[15] In Pournelle's future history, the CoDominium authority discourages scientific research; only renegade physicist Marie Ward remembers the old idea of black holes, and she theorizes that a stellar black hole is causing passing vessels to drop out of hyperspace and trapping them in its gravity well (for an instance of a quantum black hole precipitating ships out of hyperspace, see "The Borderland of Sol" by Larry Niven, below). Captain Bartholomew Ramsey commands a likely-to-be suicidal mission along the fateful trajectory to test the theory, and finds it all too true and himself with his own craft trapped right alongside the missing—and grotesquely damaged—ships. Following a hunch of Ward, a heroic officer (and Ramsey's romantic rival) volunteers to pilot the most spaceworthy of the hulks straight into the hole, to unleash a torrent of powerful gravity waves (see graphic). By turning on its short-lived Alderson drive at the precisely calculated moment of impact, Ramsey's ship is able to surf out of the well and return to 82 Eridani[note 4] with all the black hole's previous survivors on board.

- "The Hole Man" (1973): a short story written by Larry Niven and published in Analog science fiction magazine. "One day Mars will be gone." Thus begins the Hugo Award winning (1975) tale of an electromagnetically confined quantum black hole, the resonator of an ancient gravity-wave communicator discovered on a voyage of exploration to Mars.[note 5] A disgruntled and possibly psychotic mission scientist (the eponymous hole man) "accidentally" turns off the containment field at the perfect moment to murder the expedition's martinet captain, with the unconstrained singularity dropping through his body on its way to the planetary center of mass. Massing 100 billion kg, with a diameter of 0.1 fm (about a sixteenth the size of a proton[17]) the object encounters no resistance as it plunges through flesh and stone alike, too small to encounter and consume many subatomic particles, but leaving behind a channel of millimeter-scale havoc arising from the enormous tidal forces in its nanoscale neighborhood. Still, the hole will grow. The astrophysicist explains: Remember that it absorbs everything it comes near, a nucleus here, an electron there ... and it's not just waiting for atoms to fall into it. Its gravity is ferocious, and it's falling back and forth, through the center of the planet, sweeping up mass. The more it eats, the bigger it gets ... sooner or later [in 40 years], it'll absorb Mars.[18][note 3]

- The Forever War (1974), novel by Joe Haldeman. In this novel, humanity has discovered collapsars throughout the galaxy, and used them to colonise it. Spaceships and troops are also transported via the collapsars to wage war against an alien species. Due to time dilation, these trips are subjectively very brief, but decades or centuries pass elsewhere. The difficulties the troops face in reintegrating to a vastly changed society after returning from a campaign is a key theme.

- "The Borderland of Sol" (1975): a Known Space novelette by Larry Niven published in Analog science fiction magazine. Lovesick Jinxian physicist Dr. Julian Forward has turned space pirate, using a charged quantum black hole, electrostatically steered by a trio of space tugs, to winkle interstellar transports out of hyperspace in the desolate trans-Neptunian reaches of the Solar System. When Beowulf Schaeffer's ship is attacked, its hyperdrive motor suddenly disappearing, he and ideal genetic specimen cum genius Carlos Wu find themselves prisoners in Forward's secret asteroid base even as the mad scientist plots yet another assault. Using ingenuity and dexterity, with covert logistical backup from Earth agent Sigmund Ausfaller, the two foil the ambush; the ravenous vortex of the hole escapes confinement and settles slowly—a deadly, lazily drifting actinic pinpoint—through Forward's control room. Forward loses his frantic resisting grip on a control panel, falls into the tiny maelstrom, and is consumed in a flash of light; within minutes the entire asteroid crumples in on itself and is as spectacularly annihilated. Meanwhile, the protagonists escape in the nick of time on Ausfaller's ship.[20]

- "A World Out of Time" (1976): a Larry Niven novel set in the State story universe. Jerome Corbell uses a stolen spacecraft to perform a slingshot around the supermassive black hole at the galactic center; relativistic time dilation causes him to emerge from the maneuver over three million years later.

- The Ophiuchi Hotline (1977) by John Varley: micro black holes are harvested in the Oort cloud and used to produce energy.

- Gateway (1977): the multiple award winning[21][22] first novel in the Heechee Saga by Frederik Pohl. Protagonist Robinette Stetley Broadhead signs on to a ten-person crew that is flying in a pair of ill-understood starships (two of a fleet abandoned to the Solar System by a vanished alien race, long gone into hiding from their deadly Foe, the Assassins),[23] and voyaging to a frighteningly unknown—but potentially rewarding—destination. Upon arriving there, they all fall into the clutches of a stellar-mass black hole; through a series of mishaps Broadhead escapes and returns home to fame and fortune while the other nine plunge, over the span of an objective time-dilated eternity, into the hole. The novel explores both the incident itself and Broadhead's resulting feelings of guilt. In later installments of the saga, the Heechee emerge from their retreat in the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy, having—again because of time dilation—spent only a few subjective centuries there; they and the humans resolve to confront The Foe together.

- "Fountain of Force" (1978): a short story written by Grant Carrington and George Zebrowski. Black holes, linked via wormholes to distant corresponding white holes, form the foundation of an instantaneous travel network that spans the galaxy. The story concerns the inadvertent discovery of an especially large black hole that provides a link to the Andromeda galaxy.[19]

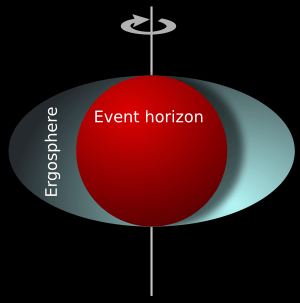

- "Killing Vector"[note 7] (1978): a short story by Charles Sheffield. In a tale that makes innovative use of black holes as an imagined power source, the mass murderer Yifter is being conveyed from Earth orbit to the Titan penal colony on a modular ship consisting of multiple independent spherical Sections, each drawing power from the ergosphere (see graphic) of its own rapidly rotating quantum hole, or "kernel," the whole assembly being electromagnetically bound together. Yifter is freed in a deep-space raid by his henchmen, but is tricked into making his getaway in Section Seven, whose kernel has been experimentally stripped of its Killing vector and thereby exposed as a naked singularity; as soon as he taps the ergosphere he is flung into another dimension.[19]

- "Singularity" (1978): a short story by Mildred Downey Broxon. A scientific team monitors the last days of the intelligent but radically alien tribes of Epsilon Eridani's second planet, Mancken's World, as a wandering stellar black hole finds its way through the star's planetary system. The hole makes a feast of the gas giant fifth planet but passes nowhere near Mancken's; however on its close encounter with ε Eridani itself, it will raise a storm of huge planet-scouring flares. The autochthones, whose prescient mythology has left them not unprepared for the event, calmly await the apocalypse along with a lone abandoned—and fearful—human observer.[24]

- "The Nothing Spot" (1978): a short story by Dan Girard. Future housewife Cheryl Harbottle is dismayed to discover that, in her new decorator lamp ("Capture the Sun in Your Living Room"), the microscopic solar lighting element has collapsed into a microscopic black hole, which consumes just about anything she experimentally feeds into it. After losing her Komfy Kushion chair she begins to get really scared until, ever resourceful, she conceives the idea of cordoning off the nothing spot's corner with some tasteful drapes and discontinues her rubbish disposal service.[25]

- Star Bright (1980): a novel by Martin Caidin. A nuclear fusion experiment gone awry leads to the creation of an object that has all the properties of a quantum black hole, although it is not called that in the novel. There is a large explosion, consistent with the energy released by the total evaporation of a singularity via Hawking radiation, and a wide area is devastated.[26]

- The Gates of Heaven (1980): a novel by Paul Preuss. In the near future, an expedition attempts to rescue the survivors of the first accidental interstellar journey. Passage through the null-tide region between a pair of black holes is actually a gateway to another star system. A sequel, Re-entry, is set centuries in the future. A government agent tracks down a fugitive who has discovered how to use the black hole gateways to travel back in time and possibly undo history. (In the end, the gateways don't merely link different points light-years apart in the universe, but they actually connect different indistinguishable universes in a multiverse.)[27]

- The Doomsday Effect (1986): a novel by Thomas Thurston Thomas, a.k.a. Thomas Wren. A tiny black hole falls into the Earth, and begins an elliptical orbit through it, consuming it as it goes. Scientists labor to figure out how to stop it. But how do you stop something that is smaller than an atom, heavier than a mountain, and swallows everything that touches it? Winner of the Compton Crook Award in 1987.[28]

- Hyperion (1989): a novel by Dan Simmons. In the far future, Earth is only a memory. In "The Poet's Tale" Martin Selenius, author of the fictional epic poem The Hyperion Cantos, reminisces about his land-poor aristocratic upbringing on Earth in the time of the Big Mistake, enjoying "periods of remission"—stretches of ten to eighteen quiet months between planet-wide spasms as the Kiev Team's goddamn little black hole digested bits of the Earth's center and waited for its next feast ... The devastation was great during the Bad Times—and these came more often in precisely plotted spasms ...[29] (for a similar catastrophe on the planet Mars, see The Hole Man by Larry Niven, above). It is later revealed that the Big Mistake was no mistake at all, but an event engineered by the TechnoCore which later, for reasons of its own, constructed a complete virtual simulacrum of Old Earth.

- Beyond the Fall of Night (1990): the sequel by Gregory Benford to Arthur C. Clarke's earlier work Against the Fall of Night. The sequel is very different in tone and theme from its inspiration, and ignores Clarke's own revision The City and the Stars (see above).[6] In it Benford explicitly renames the Singularity that imprisons the Mad Mind, from Clarke's Black Sun (at the edge of the galaxy) to the Black Hole (an SMBH at the center of the galaxy): The Mad Mind's strange sentience had been confined to the warped space-time near a huge black hole. Only the restraining curvature there could hold it in place for long ... Around the black hole orbited a disk made of infalling matter, flattened into a thin plate, spinning endlessly. The inner edge of the disk was gnawed into incandescent ferocity by the compressive clawing of the hole’s great tidal gradients.[note 8] There the Mad Mind had been held by the swirl and knots of vexed space-time, ... swimming upstream forever against the infall of matter in the accretion disc.[30] Benford reworked the same theme yet a third time in a reissue of the novel as Beyond Infinity (2004, ISBN 0-446-53059-X, see below) wherein the protagonist Alvin of Loronei, a "Unique," is replaced by the young woman Cley, an "Original"; the Black Hole becomes the black hole; and the Mad Mind becomes the Malign.

- Earth (1990): a novel written by David Brin. The plot of the book involves an artificial quantum black hole which has been lost in the Earth's interior and the attempts to recover it before it destroys the planet (for a similar catastrophe on the planet Mars, see The Hole Man by Larry Niven, above). The events and revelations which follow reshape humanity and its future in the universe. But where did the hole come from? How could anybody build and conceal a black hole, for heaven’s sake—even a micro black hole—in space without word getting out? The smallest hole with a [Hawking radiation] temperature low enough to be contained would need the mass of a midget mountain. You don’t go hauling that kind of material into low earth orbit without someone noticing.[31]

- Better Than Life (1990), novel written by Grant Naylor, features the crew of Red Dwarf encountering a black hole, nearly sucking them in to their demise, which they manage to escape from utilizing black hole physics devised by the freshly genius Holly and retained by a talking toaster (but still have to briefly go through "spaghettification" - merging them into strands of shared consciousness). The resultant time dilation separates them from the marooned Dave Lister for 37 years, making him too weak to survive a Polymoprh attack. The crew are able to resurrect him by travelling back through the black hole to a region called the omni-zone, which allows for travel into six parallel universes, including one where time runs backwards. This serves as the background for both alternative sequels, written by Doug Naylor and Rob Grant respectively, called Last Human (1995) and Backwards (1996). The omni-zone plays a more vital role in the former, as it features numerous effects of interchange through the black hole between universes.

- Chaos and Order (1994), fourth book of The Gap Cycle, a science fiction series and floridly characterized space opera homage[32] by Stephen R. Donaldson. Pursued by a police battle cruiser, a bounty hunter, and an alien Amnion ship, sometime pirate captain Angus Thermopyle heads his vessel, the Trumpet, for an illegal lab hidden deep in a chaotic asteroid belt. ... she carried singularity grenades; devices at once so dangerous and so difficult to use that Morn’s instructors in the Academy had dismissed their value in actual combat … Without external energies to feed it, the singularity was so tiny that it consumed itself and winked away before it could do any damage.[33] Here Donaldson recognizes the brief lifetime of sufficiently small quantum singularities, but he greatly understates the energy they produce when they "wink away"[note 9]—a release of energy that would actually serve as a far more effective weapon than the highly localized "appetite" of a tiny black hole.

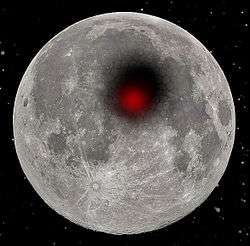

- "How We Lost the Moon, a True Story by Frank W. Allen" (1999), short story by Paul J. McAuley, published in the collection Little Machines. A quantum black hole is accidentally created on the Moon and gradually consumes it (see graphic; for a similar catastrophe on the planet Mars, see The Hole Man by Larry Niven, above).[34]

- Eater (2000), novel by Gregory Benford. In the early 21st century, astronomers detect what appears to be a distant gamma-ray burster, a black hole engulfing a star light years away. It soon becomes apparent that the hole is smaller and closer than that, and rapidly approaching the Earth, swallowing asteroids and interplanetary debris on the way, and finally that it hosts an intelligent being, one created by "a very early, intelligent civilization whose planet was being chewed up by the black hole,"[35] and who had uploaded their consciousnesses to it. The "Eater" would like to similarly absorb the best and brightest minds of Earth, and the destruction of humanity looms unless three astronomer protagonists, collectively playing Theseus to the black hole's Minotaur, can interfere with the increasingly malevolent entity's plans.

- Ilium (2003) and Olympos (2005), linked pair of novels by Dan Simmons. In this duology, one of the story's multiple threads is played out in Paris Crater—a future metropolis rebuilt on the ruins of the former French capital … Paris Crater was said to have gained its crater more than two millennia ago when post-humans lost control of a tiny black hole they’d created during a demonstration at a place called the Institut de France. The hole had bored its way through the center of the earth several times but the only crater it had left in the planet’s surface was right here between the Invalids Hotel faxnode and the Guarded Lion node.[36] The hole evaporated with an enormous release of energy.[note 9]

- Beyond Infinity (2004), reissue of Beyond the Fall of Night (see above) by Gregory Benford; the cover art of the hardcover edition features a SMBH with a prominent polar jet, at the hub of a spiral galaxy. In this version Benford, a leading writer of hard science fiction that nonetheless possesses a lyrical aspect,[37] has finally assumed full ownership of Arthur C. Clarke's Black Sun (see The City and the Stars above), replacing it with a physically plausible yet ingenious cosmic prison for Clarke's Mad Mind (the Malign).

- Exultant (2004), novel in the Xeelee Sequence written by Stephen Baxter. In this and other novels of the sequence, humanity is (again) expanding into the galaxy, and waging a fierce war of aggression on the enormously advanced but far less numerous Xeelee. Life is everywhere in the universe, and everywhere intimately bound up with black holes. The first life forms developed within Planck time of the Big Bang; the first Xeelee inhabited primordial black holes; when those began to evaporate, they moved to the supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies—including the one named Chandra in our own—and became an integral part of the holes' complex ecologies of living species. Humanity finally drives the Xeelee from the periphery of the galaxy and confines them to Chandra, which it attacks with singularity cannons, projecting pairs of black holes whose trajectories converge to disrupt the central black hole's event horizon with eruptions of gravity waves, threatening all the species within. Hoping to save their cohabitants, the Xeelee flee the Milky Way and effectively end the war.

- In Zombie Bums from Uranus (2003), a fictional type of astronomical body (called a brown hole) is mentioned. It is stated that brown holes form when a vast interstellar butt runs out of gas and collapses in on itself, and that they force objects into random places, possibly including time travel.

Contemporary

- Dark Peril by James C. Glass (published in Analog March, 2005), is a story about space travelers on an exploratory mission. While they investigate a strange cosmological phenomenon, their two small space crafts begin to shake, and they are unable to leave the area. One crew member realizes that they are trapped in the Ergosphere of a black hole or naked singularity. The story describes a cluster of multiple black holes or singularities, and what the crew does to try to survive this seemingly inescapable situation.

- The novel The Black Hole Project by G. David Nordley (with C. Sanford Lowe), based on five novellas originally published in Analog in 2006 and 2007 ("Kremer's Limit", "Imperfect Gods", "The Small Pond", "Loki's Realm", and "Vertex"), concerns an interstellar project to create an artificial Black Hole, and the political, militaristic, and terroristic activities undertaken fore and against the project.

- Jeffrey A. Carver's 2008 novel Sunborn, includes an ancient race of artificial intelligences known as "Survivors", which live "within compact dimensions revealed only in "extreme space"—most likely in close proximity to, or inside, super-massive black holes." It is a hostile race, intent on the destruction of all organic life; and to that end they intend, among other things, to create more black holes by causing Supernovas and hypernovas. The book has a subplot involving a weapon deployed against Earth, which has a Quantum singularity as one of its components. The book also includes space-dwelling creatures called Deeaab and Daarooaack (Deep and Dark, respectively, for short), which are, in part, described with the following statement by another character: "whatever they were in their own universe, here they took the form of singularities distributed over measurable space. That's why they can affect spacetime in ways that might otherwise seem unlikely."

- Brian Greene's 2008 novella Icarus at the Edge of Time is a science fiction retelling of Icarus' tale. It is the story of a young man who runs away from his traveling, deep-space home to explore a black hole.

Film and television

- The Black Hole (1979), a major science fiction film featuring a derelict ship at the edge of a black hole.

- The Black Hole (2006), a science fiction film unrelated to the 1979 film.

- Event Horizon (1997), a spaceship is created to travel faster than light to Alpha Centauri through the use of a machine that creates an artificial black hole. The ship accidentally passes into another dimension and mysteriously returns seven years later, found derelict in orbit around Neptune with the entire crew missing. A salvage crew discovers that the black hole passed the ship through a Hell-like dimension that drove the original crew insane, causing them to massacre each other, and return the ship with a malevolent intelligence of its own.

- Zathura (2005) It is revealed that Zathura is a giant black hole.

- Treasure Planet (2002), in Disney's animated sci-fi version of Treasure Island, the RLS Legacy encounters a black hole, where a ruthless crew member named Scroop (Michael Wincott) cuts the lifeline of the overboard First Mate, Mr. Arrow (Roscoe Lee Browne), who is then pulled to his death in the black hole.

- Wristcutters: A Love Story (2006), a fantasy romantic comedy which features a black hole under a car's front passenger seat where things dropped into it vanish, and who the lead character escapes the afterlife from.

- Space Battleship Yamato: Resurrection (2009), A wandering cascade black hole is on a trajectory toward Earth. While escorting evacuation ships to a far away solar system, the Yamato and her crew have to find a way to stop it before Earth is destroyed.

- Star Trek (2009), "red matter" is used by Spock to create an artificial black hole to absorb a supernova, and later by Nero to destroy Vulcan. Traversing through the black hole created caused the characters to travel through time and ultimately change the past.

- Maximum Shame (2010), a black hole is coming to swallow Earth and a couple escapes into a parallel universe.

- In the Star Trek universe, the Romulans are known to utilize artificial black holes (generally referred to as "artificial quantum singularities") as a power source. In at least two episodes, malfunctions cause "temporal anomalies" (abnormal time flow).

- In the television sci-fi adventure series Andromeda (2000), a black hole named Marida slows time for the human half of the lead character, Captain Dylan Hunt, and his sentient space warship, the Andromeda Ascendant (Glorious Heritage class) allowing him to survive into a new era by spending 303 years in a moment.

- Several adventures in the British television series Doctor Who feature black holes or situations relating to them, notably "The Impossible Planet", "The Satan Pit", "The Horns of Nimon", "The Three Doctors" and "The Deadly Assassin". Furthermore, the Eye of Harmony is a black hole used by the Time Lords as a power source for their "TARDIS" time machines. It is kept beneath the Panopticon, the hall of government in their Citadel, and in the original series links the TARDISes together. In the new series episode "Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS" there is a power room where the collapsing star that created the black hole is shown.

- In the Blake's 7 story "Breakdown" the Liberator travels through a black hole.

- In the Stargate SG-1 episode A Matter of Time, a wormhole is opened to a planet near the event horizon of a black hole, causing the gravitational and time dilation effects of the black hole to threaten Earth. Black holes play a major role in Stargate SG-1, and appear in many episodes. Multiple episodes utilize black holes as power sources for intergalactic-range wormholes. In another episode, the same black hole that threatened Earth was used to make a star explode, destroying an entire fleet of Goa'uld ships.

- In the Battlestar Galactica episode "Daybreak Part 2", the Cylon Colony orbits a black hole.

- In the anime Yugioh GX, the main antagonist is the Light of Destruction, which is a sentient white hole

- In the Superman: The Animated Series episode Absolute Power, a black hole acts as a major plot device.

- In the Transformers episode called "the Killing Jar", Ultra Magnus, Cyclonus, Wreck-Gar and several other characters are transported through a black hole, only to find themselves trapped in a universe composed entirely of anti-matter.

- In Thor: The Dark World, the Dark Elves use detonation devices to produce small black holes that last a few seconds while sucking in anything that is caught within the blast radius.

- In Barna Hedenhös uppfinner julen (2013), a stellar black hole in outer space opens a time portal between the Stone Age and 2013 causing the Hedenhös family to end up in contemporary Stockholm using their Stone Age-rocket spacecraft.[38]

- In Interstellar (2014), a wormhole leads to a supermassive black hole called Gargantua, located 10 billion light-years from Earth and is orbited by several planets. Its mass is 100 million times that of Earth's sun, and it is spinning with 99.8 percent of the speed of light.[39] For one of the planets, named Miller's planet, one hour equals seven years on Earth due to dramatic time dilation induced by the close proximity to Gargantua.

- The main villain in the anime Transformers Cybertron is a sentient one called the Grand Black Hole (the Unicron Singularity in the dubbed version) created by the destruction of Unicron in the previous series.

- In the "Homer Cubed" segment of Treehouse Of Horror VI, Homer Simpson finds himself trapped in a strange computer-generated dimension just outside his own animated reality. After accidentally destabilizing this dimension, it collapses into a black hole, which draws Homer through a wormhole into our own reality.

- In the 2015 French Science-Fiction film The Big Everything, black holes of the Microquasar type are used as a central plot device, creating a path through the Universe.

Comics

- In the anime/manga series Inuyasha, the monk Miroku is cursed with a black hole in his right hand that is capable of drawing anything into the void, dubbed the Wind Tunnel. The hereditary curse was placed on his grandfather by the demon Naraku, and grows each year in size, threatening to draw Miroku himself into the hole when it reaches its limit, thus killing him.

- The X-Men comic series featured a storyline in which a mad Shi'ar emperor, D'Ken, attempted to shatter a lattice called the M'Krann Crystal, which was said to contain an entire galaxy of black holes all occupying the same space, and which would have destroyed the entire Marvel Universe had the crystal's matrix been breached; his efforts were ultimately thwarted by the efforts of the Phoenix, who used her vast powers to repair it.

Music

- The "Cygnus X-1" song series by Rush tells the story of an interstellar traveler who becomes trapped in the event horizon of Cygnus X-1. The traveler appears at first to be destroyed, but eventually re-emerges in a world resembling the Olympus of Greek mythology. The song cyle begins at the end of the album A Farewell to Kings and concludes at the beginning of the band's following studio album Hemispheres.

Games

- In the video games Super Mario Galaxy and Super Mario Galaxy 2, black holes are the equivalent of bottomless pits in which if Mario (or Luigi) falls or slips off an edge with a black hole under the level, he will be sent spiraling into it, losing a life on purpose. In the end of the first game, when Mario defeats Bowser, his galaxy collapses into a supermassive black hole and starts consuming the universe. Only the Lumas were able to neutralize the super massive black hole.

- In the video game Mega Man 9, there is a weapon called the Black Hole Bomb. When Galaxy Man uses it, it pulls Mega Man toward its horizontal position while Galaxy Man stands under it to cause damage. Mega Man can use the weapon after defeating Galaxy Man to suck enemies and bullets into a black hole, and it is effective against Jewel Man in the same game.

- In StarCraft II, a Protoss unit, called The Mothership, can summon a black hole, which sucks up all nearby units and disables them for a short time.

- In Defense of the Ancients and its sequel, Dota 2, there is a hero called Enigma who can generate a black hole that pulls in enemies and damages them. There is speculation on Enigma's lore that he is a sentient black hole himself, or the personification of the force of gravity.

- In Star Ocean: The Last Hope, the SPSS-6002B-003 Calnus travels through a black hole which somehow leads to a parallel universe.

- In a videogame called The Darkness, you end up going to a turkish bath and eventually kill a crazy man, for which in return, you gain the ability to summon a mini black hole and to collapse it at will.

- In the fourth installment of Destroy All Humans! Path of the Furon, you acquire a new upgrade for Crypto's gun later in the game called the Black Hole Gun, in which it creates one after charging the weapon and firing.

- In Mass Effect 2 the main base of the Collectors exists on the border of the event horizon of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy. The biotic ability Singularity used in the game also creates a miniature black hole which pulls enemies off their feet and deals damage to them

- In Call of Duty: Black Ops Zombies mode, a tactical grenade called the Gersch Device, appears in the maps Ascension and Moon. Gersch Devices were miniature "black hole" creators that pulls zombies toward it, giving players a break or a chance to revive a downed teammate.

- In Bungie's award-winning Halo Series, the method of faster-than-light travel for spacecraft is through a nondimensional domain known as 'Slipspace', and is made possible by ripping the space-time continuum by having slipspace drives artificially generating thousands of micro black holes that quickly evaporate via Hawking radiation.

- In the computer game Master of Orion II one of the weapons a player can use is a micro black hole generator, which is used to immobilize and destroy enemy ships.

- In a promotional video for the video game Portal 2, the Aperture Science Handheld Dual Portal Device is shown to have a miniature black hole and event horizon approximation ring.

- In Super Robot Taisen: Original Generation, a video game by Banpresto, the original Huckebein is using black hole engine as power source which eventually exploded during test run.

- In Solar 2 if you get enough mass you will become a black hole. There is also a mission were you must push a "Black hole Asteroid" into a solar system.

- In Spore (2008 video game), the player can travel through Black Holes with the usage of a tool named the Wormhole Key.

- In Saints Row IV, the player can weaponize temporary black holes using a gun named the "Black Hole Launcher" or "Singularity Gun".

- In Sonic Riders: Zero Gravity, a floating island known as Babylon Garden comes to possess so much gravitational force, it collapses in on itself and becomes a black hole.

- In Diablo 3, the wizard character class gains access to an ability named Black Hole. This ability creates a small black hole for a couple of seconds, which draws enemies in while damaging them.

- In Metroid Prime 2: Echoes, Samus can combine her dark beam with the missile launcher to create a black hole that pulls in all enemies in a short range known as the "Darkburst"

- In "Death:The Partaking",It is shown that Death itself will be swallowed by A God Black Hole.

- In Heart of Darkness, the center of the Darkland and final stage of the game is a black hole that is crucial to the plot.

See also

Black holes may be referred to as locations in space, in fiction. For a list containing many stars and their planetary systems that appear in fiction, see Stars and planetary systems in fiction.

External links

- The Truth About Black Holes: Science Fiction

- Black Holes: Stranger Than Fiction

- Science Fiction with Good Astronomy and Physics

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The idea of a Black Sun has been variously exploited in the science fiction literature. In "To B or Not to C or to D" (1950), Jack Vance describes Noir, the dark companion star, as consisting of "dovetailed protons," a fair description of the outer core, or neutron-proton fermi liquid layer of a neutron star. In "Legends of Smith's Burst" (1959), Brian Aldiss' black sun is an antimatter star that radiates an all-enveloping darkness rather than simply enclosing it. In the present instance, Gregory Benford and possibly Arthur C. Clarke use the term to refer to a black hole. Finally, in Black Sun Rising (1991), C. S. Friedman uses her eponymous star as a parapsychic nexus that ensnares men's souls.

- ↑ The Kyrie is a prayer of the Christian liturgy that includes in part Anderson's quoted lines Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. Kyrie eleision ... "Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine on them. Lord have mercy ... ," an ironic prayer indeed in light of the story's denouement.

- 1 2 Niven makes his black hole massive enough to avoid near-term quantum evaporation—but he makes significant errors of classical physics in his description of the fate of the red planet. First, in stating that the singularity would "fall back and forth, through the center of the planet" the author neglects the initial horizontal velocity component lent the object by Mars' rotation. On its release from confinement the hole, meeting no resistance, would execute a two-dimensional simple harmonic oscillation (describing an ellipse, as correctly described by Charles Sheffield in his story "Killing Vector"[19]) inside the planet as Mars rotated freely around it. Treating the planet as a fixed frame of reference, the path of the black hole inside it would be a three-dimensional hypotrochoid analog that would in time densely trace a biconic spool-shaped solid (see hyperboloid of one sheet) bounded on the north and south by the release latitude L0 (the graphic shows the flat example with L0 = 0°).

With an equatorial release, the singularity describes a free-falling hypotrochoid inside Mars, sweeping out a CD shaped great-circular slice.

With an equatorial release, the singularity describes a free-falling hypotrochoid inside Mars, sweeping out a CD shaped great-circular slice.But would the singularity in fact meet no resistance to its buried trajectory? Remember that it leaves a path of tidal disruption in its train (We looked for, and found, a hole in the floor beneath the communicator. It was the size of a pencil lead, and packed with dust ... [the quantum black hole] pulverized the material of the floor.) It takes physical work to produce disintegration like that. Through steady energy loss to the destruction in its wake, the hole would follow a rapidly decaying underground orbit, and soon come to rest more or less harmlessly at the center of the planet.

- ↑ Later in the story (pp 47; 70) Pournelle refers twice to the star as 81 Eridani, an apparent editorial error. In spite of majority rule, it is probable that he really meant the once-mentioned 82 Eridani, a well-known star 20 ly from the Earth, with an apparent magnitude of 4+ (and the subject of several other science fiction stories), rather than its Gould catalog predecessor 81 Eridani, a nondescript star about which little is known. In 2011, long after this story was written, three Super-Earths were confirmed in orbit around 82 Eridani (HD20794).[16]

- ↑ For another quantum black hole discovered in an ancient precinct on the Red Planet, with quite a different outcome, see The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett, above.

- ↑ In actual ion thrusters, electrons are either injected or allowed to escape from the body of the engine into the positively charged ion thrust beam in order to neutralize it. This blocks the buildup of a negative charge on the spacecraft that would retard the flight of the positive ions in the exhaust, preventing the development of thrust. However, since Forward needed a beam of positive ions, he may have disabled the neutralizing feature and grounded his thruster to drain off its negative charge.

- ↑ The Killing vector field, named after German mathematician Wilhelm Killing, is a vector function employed in the relativistic theory of black holes—and not normally an instrument of death, although Sheffield does make pivotal use in the story of the pun on the gerund "killing" with regard to Section Seven. Another possible pun on the title is the killing vector represented by Yifter's genocidal global dispersal of persistent hallucinogens into Earth's water supplies.

- ↑ Benford here neglects the fact that, near the event horizon of a supermassive black hole, tidal forces are in fact rather weak.

- 1 2 For comparison, according to the Hawking radiation theory, a 1-second-lived black hole has a mass of 2.28×105 kg, equivalent to an energy of 2.05×1022 J that could be released by 5×106 megatons of TNT, and all its mass is converted to energy.

References

- ↑ Mann, George (2001). "Black Hole". The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. London: Robinson Publishing. p. 468. ISBN 1-84119-177-9.

In science fiction, black holes have become a standard method of portraying faster-than-light space travel.

- ↑ Brackett, Leigh (2009). The Sword of Rhiannon. Redmond, WA: Paizo Publishing. ISBN 1-601-25152-1.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Brackett, Leigh (Douglass)". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 150. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Cameron, Eleanor (Butler)". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 185. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Cameron, Eleanor (2003). Stowaway to the Mushroom Planet. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Publisher Inc. pp. 159; 198; 205. ISBN 0-844-67237-8.

- 1 2 Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Clarke, Arthur C". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 230. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C (2001). The City and the Stars. New York: Aspect. p. 264. ISBN 0-446-67796-5.

- ↑ Spitzer, L (1987). Dynamical Evolution of Globular Clusters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08309-6.

- ↑ Niven, Larry (1968). "At the Core". Neutron Star. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 52; 66–67.

- ↑ Pournelle, Jerry (1978). "Kyrie". Black Holes. Brooklyn NY: Fawcett Books Group. pp. 105; 107. ISBN 0-449-23962-4.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Zelazny, Roger (Joseph)". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 1367. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Zelazny, Roger (1969). Creatures of Light and Darkness. New York: Harper Voyager. p. 160. ISBN 0-061-93645-6.

- ↑ Finkelstein, D (1958). "Past-Future Asymmetry of the Gravitational Field of a Point Particle". Physical Review. 110 (4): 965–967. Bibcode:1958PhRv..110..965F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.110.965.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Black Holes". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. pp. 129–131. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Pournelle, Jerry (1978). "He Fell into a Dark Hole". Black Holes. Brooklyn NY: Fawcett Books Group. p. 42. ISBN 0-449-23962-4.

- ↑ Pepe, F; Lovis, C; Ségransan, D; et al. (2011), "The HARPS search for Earth-like planets in the habitable zone: I – Very low-mass planets around HD20794, HD85512 and HD192310", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 534: A58, arXiv:1108.3447

, Bibcode:2011yCat..35349058P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117055

, Bibcode:2011yCat..35349058P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117055 - ↑ Cottingham, W N; Greenwood, D A (2001). An Introduction to Nuclear Physics (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-521-65733-4. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ↑ Niven, Larry (1974). "The Hole Man". A Hole in Space. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 142–145. ISBN 0-345-24011-1.

- 1 2 3 Pournelle, Jerry (1978). "Fountain of Force". Black Holes. Brooklyn NY: Fawcett Books Group. p. 199. ISBN 0-449-23962-4.

- ↑ Niven, Larry (1975). Tales of Known Space. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 197. ISBN 0-345-24563-6.

- ↑ "1977 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ "1978 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Pohl, Frederik". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 943. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Pournelle, Jerry (1978). "Singularity". Black Holes. Brooklyn NY: Fawcett Books Group. p. 242. ISBN 0-449-23962-4.

- ↑ Pournelle, Jerry (1978). "The Nothing Spot". Black Holes. Brooklyn NY: Fawcett Books Group. p. 294. ISBN 0-449-23962-4.

- ↑ Caidin, Martin (1980). Star Bright. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-12621-0.

- ↑ Preuss, Paul (1980). The Gates of Heaven. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-13409-4.

- ↑ Thomas, Thomas (1986). The Doomsday Effect. New York: Baen Books. ISBN 0-671-65579-5.

- ↑ Simmons, Dan (1990). Hyperion. New York: Spectra. pp. 182–183. ISBN 0-553-28368-5.

- ↑ Benford, Gregory (1991). Beyond the Fall of Night. New York: Berkley Books. pp. 271; 305. ISBN 0-441-05612-1.

- ↑ Brin, David (1991). Earth. New York: Bantam Spectra. p. 173. ISBN 0-553-29024-X.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Donaldson, Stephen R.". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. pp. 347–348. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Donaldson, Stephen R (1995). Chaos and Order: The Gap Into Madness. New York: Spectra. p. 556. ISBN 0-553-57253-9.

- ↑ "How We Lost the Moon, a True Story by Frank W. Allen". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ↑ Benford, Gregory (2001). Eater. New York: Harper Voyager. p. 160. ISBN 0-380-79056-4.

- ↑ Simmons, Dan (2006). Olympos. New York: Harper Voyager. p. 271. ISBN 0-380-81793-4.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Benford, Gregory". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin’s Griffin. p. 108. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ "Familjen bakom julkalendern" (in Swedish). Sydsvenska. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ↑ The Science of 'Interstellar' Explained (Infographic)