Bivalirudin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Angiomax |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous injection/infusion only |

| ATC code | B01AE06 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | N/A (IV application only) |

| Metabolism | Angiomax is cleared from plasma by a combination of renal mechanisms and proteolytic cleavage |

| Biological half-life | ~25 minutes in patients with normal renal function |

| Identifiers | |

| Synonyms |

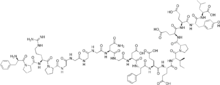

d-Phenylalanyl-l-prolyl-l-arginyl -l-prolylglycylglycylglycylglycyl-l-asparaginylglycyl -l-alpha-aspartyl-l-phenylalanyl -l-alpha-glutamyl-l-alpha-glutamyl-l-isoleucyl -l-prolyl-l-alpha-glutamyl-l-alpha-glutamyl -l-tyrosyl-l-leucine |

| CAS Number |

128270-60-0 |

| PubChem (CID) | 16129704 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 6470 |

| DrugBank |

DB00006 |

| ChemSpider |

10482069 |

| UNII |

TN9BEX005G |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:59173 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1201455 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C98H138N24O33 |

| Molar mass | 2180.29 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Bivalirudin (Angiomax or Angiox, manufactured by The Medicines Company) is a specific and reversible direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI).[1]

Chemically, it is a synthetic congener of the naturally occurring drug hirudin (found in the saliva of the medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis).

Bivalirudin is a DTI that overcomes many limitations seen with indirect thrombin inhibitors, such as heparin. Bivalirudin is a short, synthetic peptide that is potent, highly specific, and a reversible inhibitor of thrombin.[1][2][3] It inhibits both circulating and clot-bound thrombin,[3] while also inhibiting thrombin-mediated platelet activation and aggregation.[4] Bivalirudin has a quick onset of action and a short half-life.[1] It does not bind to plasma proteins (other than thrombin) or to red blood cells. Therefore, it has a predictable antithrombotic response. There is no risk for Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia/Heparin Induced Thrombosis-Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (HIT/HITTS).[1] It does not require a binding cofactor such as antithrombin and does not activate platelets.[2][5] These characteristics make bivalirudin an ideal alternative to heparin.

Bivalirudin clinical studies demonstrated consistent positive outcomes in patients with stable angina, unstable angina (UA), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing PCI in 7 major randomized trials.[1][3][4][6][7] Patients receiving bivalirudin had fewer adverse events compared to patients that received heparin.[8][9]

Indications

US (United States) Indications:[1]

- Bivalirudin is indicated for use as an anticoagulant in patients with unstable angina undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA).

- Bivalirudin with provisional use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI) is indicated for use as an anticoagulant in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

- Bivalirudin is indicated for patients with, or at risk of HIT/HITTS undergoing PCI.

- Bivalirudin is intended for use with aspirin and has been studied only in patients receiving concomitant aspirin

EU (European) indications:[10]

- Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), including patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing primary PCI.

- Bivalirudin is also indicated for the treatment of adult patients with unstable angina/non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (UA/NSTEMI) planned for urgent or early intervention.

- Bivalirudin should be administered with aspirin and clopidogrel.

Basic chemical and pharmacological properties

Mechanism of action[1]

Bivalirudin directly inhibits thrombin by specifically binding both to the catalytic site and to the anion-binding exosite of circulating and clot-bound thrombin. Thrombin is a serine proteinase that plays a central role in the thrombotic process. It cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin monomers, activates Factor V, VIII, and XIII, allowing fibrin to develop a covalently cross-linked framework that stabilizes the thrombus. Thrombin also promotes further thrombin generation, and activates platelets, stimulating aggregation and granule release. The binding of bivalirudin to thrombin is reversible as thrombin slowly cleaves the bivalirudin-Arg3-Pro4 bond, resulting in recovery of thrombin active site functions.[11]

Pharmacokinetics[1]

- Following an IV bolus of bivalirudin of 1 mg/kg and a 4-hour 2.5 mg/kg/h IV infusion a mean steady state concentration of 12.3 ± 1.7 µg/mL is achieved

- Bivalirudin is cleared from plasma by a combination of renal mechanisms and proteolytic cleavage

- Half-life:

-Normal renal function (≥ 90 mL/min) = 25 minutes

-Mild renal dysfunction (60–89 mL/min) = 22 minutes

-Moderate renal dysfunction (30-59 mL/min) = 34 minutes

-Severe renal dysfunction (≤ 29 mL/min) = 57 minutes

-Dialysis-dependent = 3.5 hours

- Clearance is reduced approximately 20% in patients with moderate and severe renal impairment and by 80% in dialysis-dependent patients

- Bivalirudin is hemodialyzable and approximately 25% is cleared by hemodialysis.

Pharmacodynamics[1]

Coagulation times return to baseline approximately 1 hour following cessation of bivalirudin administration.

Dosing and administration

Bivalirudin is intended for IV use only and is supplied as a sterile, lyophilized product in single-use, glass vials. After reconstitution, each vial delivers 250 mg of bivalirudin.

US dosing:[1]

- PCI Bolus: 0.75 mg/kg

- PCI Infusion: 1.75 mg/kg/h

EU dosing:[10]

- UA/NSTEMI

-Bolus: 0.1 mg/kg

-Infusion: 0.25 mg/kg/h for up to 72 hours for medical management

-If patient proceeds to PCI, an additional bolus of 0.5 mg/kg of bivalirudin should be administered before the procedure and the infusion increased to 1.75 mg/kg/h for the duration of the procedure.

- PCI

-Bolus: 0.75 mg/kg

-Infusion: 1.75 mg/kg/h

- Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG)

-Patients proceeding to CABG surgery off-pump:

The IV infusion of bivalirudin should be continued until the time of surgery. Just prior to surgery, a 0.5 mg/kg bolus dose should be administered followed by a 1.75 mg/kg/h infusion for the duration of the surgery.

-Patients proceeding to CABG surgery on-pump:

The IV infusion of bivalirudin should be continued until 1 hour prior to surgery after which the infusion should be discontinued

Five minutes after the bolus dose has been administered, an activating clotting time (ACT) should be performed and an additional bolus of 0.3 mg/kg should be given if needed.[1]

Continuation of the bivalirudin infusion following PCI for up to 4 hours post-procedure is optional, at the discretion of the treating physician. After 4 hours, an additional IV infusion of bivalirudin may be initiated at a rate of 0.2 or 0.25 mg/kg/h for up to 20 hours, if needed.[1][10]

Bivalirudin should be administered with optimal antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel).[1][10]

Renal impairment

A reduction in the infusion dose of bivalirudin should be considered in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment. If a patient is on hemodialysis, the infusion should be reduced to 0.25 mg/kg/h. No reduction in the bolus dose is needed.[1][10]

Safety information

Bivalirudin is contraindicated in patients with active major bleeding and hypersensitivity to bivalirudin or its components. (In the EU bivalirudin is also contraindicated in patients with an increased risk of bleeding due to hemostasis disorders and/or irreversible coagulation disorders, severe uncontrolled hypertension, subacute bacterial endocarditis, and severe renal impairment [GFR<30 ml/min] and in dialysis-dependent patients).[1][10]

Bivalirudin is an anticoagulant. Therefore, bleeding is an expected adverse event. In clinical trials, bivalirudin treated patients exhibited statistically significantly lower rates of bleeding than patients treated with heparin plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor. The most common (≥10%) adverse events of bivalirudin are back pain, pain, nausea, headache, and hypotension.[1][10]

Bivalirudin is classified as Pregnancy Category B.[1][10]

Pediatric experience

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted pediatric exclusivity for bivalirudin, based on studies submitted in response to a written request by the FDA to investigate the use of bivalirudin in pediatric patients aged birth to 16-years old.

The submission was based on a prospective, open-label, multi-center, single arm study evaluating bivalirudin as a procedural anticoagulant in the pediatric population undergoing intravascular procedures for congenital heart disease.

Study outcomes suggest that the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) response of bivalirudin in the pediatric population is predictable and behaves in a manner similar to that in adults.[12]

Comparative results

Bivalirudin is supported by 7 major randomized trials. These trials include REPLACE-2 (Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events-2), BAT (Bivalirudin Angioplasty Trial), ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy Trial), and HORIZONS AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in AMI). A total of 25,000 patients with a low to high risk for ischemic complications undergoing PCI were evaluated. Bivalirudin with or without provisional GPIIb/IIIa demonstrated similar angiographic and procedural outcomes and improved clinical outcomes when compared with heparin plus GPIIb/IIIa.[1][4][6][7][13]

HORIZONS AMI was a prospective, randomized, open-label, double-arm multicenter trial in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI.

30 Day Results

- The incidence of net adverse clinical events (9.2% vs. 12.1%) and major bleeding (4.9% vs. 8.3%) was significantly reduced by bivalirudin monotherapy versus unfractionated heparin (UFH) plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor with similar rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (5.4 vs. 5.5%) at 30 days.

- A significant reduction in the rate of cardiac mortality in patients treated with bivalirudin monotherapy versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor was observed (1.8% vs. 2.9%) at 30 days.

- Patients receiving Angiomax monotherapy had similar rates of overall stent thrombosis (Academic Research Consortium (ARC) definition) at 30 days versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (2.5% vs. 1.9%), with the exception of acute stent thrombosis (<24 hours), which was higher for the bivalirudin-treated patients at 1.3% vs 0.3% for the UFH-GP IIb/IIIa-inhibitor-treated patients.

1-Year Results

- At 1-year follow-up, a reduction in the incidence of net adverse clinical events (15.7% vs. 18.3%) and major bleeding (5.8% vs. 4.9%) was maintained in the bivalirudin monotherapy group versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group, with no difference in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (11.9% vs. 11.9%)

- A significant reduction in the rate of cardiac mortality in patients treated with bivalirudin monotherapy versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor was maintained at 1 year in the HORIZONS AMI trial (2.1% vs. 3.8%)The incidence of stent thrombosis at 1 year was also similar between the 2 treatment groups (3.5% in the Angiomax group vs. 3.2% in the UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group).

2-Year Results

- At 2-year follow-up, a reduction in the incidence of net adverse clinical events (22.3% vs. 24.8%) and major bleeding (6.4% vs. 9.6%) was maintained in the bivalirudin monotherapy group versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group, with no difference in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (18.7% vs. 18.8%)

- A significant reduction in the rate of cardiac mortality in patients treated with bivalirudin monotherapy versus UFH plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor was maintained at 2 year in the HORIZONS AMI trial (2.5% vs. 4.2%)

- At 2-year follow-up, treatment with bivalirudin monotherapy resulted in a 25% reduction in all-cause mortality, representing 15 lives saved per 1000 patients treated (number needed to treat [NNT] = 67 to save 1 life).

- The incidence of stent thrombosis (ARC definite/probable) at 2 years was also similar between the 2 treatment groups (4.6% in the Angiomax group vs. 4.3% in the UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group).

ACUITY[4]

ACUITY was a large multicenter, prospective, open-label, 3-arm trial designed to establish the optimal antithrombotic treatment regimens in patients with UA/NSTEMI undergoing early invasive management.

30-Day Results

- Bivalirudin monotherapy provided superior net clinical outcomes compared to any heparin regimen with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (10.1% vs 11.7%) at 30 days.

- The incidence of ACUITY scale major bleeding (non-CABG) was decreased significantly by 47% in the bivalirudin monotherapy group vs the heparin with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group (3.0% vs 5.7%) at 30 days.

1-Year Results

- Bivalirudin alone demonstrated no difference in the rates of composite ischemic complications (death, MI, unplanned revascularization for ischemia) versus heparin with GP IIb/IIIa inhibition (16.4% vs 16.3%) at 12 months.

REPLACE-2[7]

REPLACE-2 was a multicenter, double-blind, triple dummy randomized clinical trial in patients with low to moderate risk for ischemic complications undergoing PCI.

30 Days

- The incidence of net adverse clinical events (9.2% vs. 10.0%) and major adverse cardiovascular events (7.6% vs. 7.1%) was reduced by bivalirudin monotherapy versus unfractionated heparin (UFH) plus a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor with significant reduction in rates of major bleeding (2.4 vs. 4.1%) at 30 days.

1-Year Results

- Differences in mortality favoring bivalirudin at 30 days and 6 months was maintained at 12 months and demonstrated a 24% risk reduction in death compared to heparin plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibition.

BAT[6]

The Phase III Bivalirudin Angioplasty Trial (BAT) was a randomized, prospective, double blind, multicenter study in patients with unstable angina undergoing PTCA.

- The composite endpoint of death, MI or revascularization occurred in 6.2% of patients treated with bivalirudin and in 7.9% of patients treated with heparin.

- Significant reductions in clinical events were maintained at 90 days with absolute benefits being sustained through 180 days.

- The incidence of major hemorrhage for the entire hospitalization period in patients assigned bivalirudin was 3.7% compared to 9.3% in patients randomized to heparin.

Guidelines

Bivalirudin has Class I recommendations in multiple national guidelines.

| Patient Type | Guidelines | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| STEMI and primary PCI | ACC/AHA/SCAI 2009 Joint STEMI/PCI Focused Update | Class I-B, IIa-B |

| UA/NSTEMI | ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for UA/NSTEMI patients | Class I-B, IIa-B |

| NSTE-ACS patients | ACCP 2008 clinical practice guidelines for patients with NSTE-ACS | Grade 1A, 2B |

| PCI | ACCP 2008 clinical practice guidelines for patients with NSTE-ACS | Grade 1B |

| Patient Type | Guidelines | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| STEMI | European Society of Cardiology 2008 | Class IIa – B |

| NSTE-ACS | European Society of Cardiology 2007 | Class IIa-B, IB |

| PCI | European Society of Cardiology 2005 | Class IIa C, IC |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Angiomax (bivalirudin) Prescribing Information" (PDF). The Medicines Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- 1 2 Anand, S. X.; Kim, M. C.; Kamran, M.; Sharma, S. K.; Kini, A. S.; Fareed, J.; Hoppensteadt, D. A.; Carbon, F.; Cavusoglu, E.; Varon, D.; Viles-Gonzalez, J. F.; Badimon, J. J.; Marmur, J. D. (2007). "Comparison of Platelet Function and Morphology in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Receiving Bivalirudin Versus Unfractionated Heparin Versus Clopidogrel Pretreatment and Bivalirudin". The American Journal of Cardiology. 100 (3): 417–424. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.02.106. PMID 17659921.

- 1 2 3 Weitz, J. I.; Hudoba, M.; Massel, D.; Maraganore, J.; Hirsh, J. (1990). "Clot-bound thrombin is protected from inhibition by heparin-antithrombin III but is susceptible to inactivation by antithrombin III-independent inhibitors". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 86 (2): 385–391. doi:10.1172/JCI114723. PMC 296739

. PMID 2384594.

. PMID 2384594. - 1 2 3 4 Stone, G. W.; McLaurin, B. T.; Cox, D. A.; Bertrand, M. E.; Lincoff, A. M.; Moses, J. W.; White, H. D.; Pocock, S. J.; Ware, J. H.; Feit, F.; Colombo, A.; Aylward, P. E.; Cequier, A. R.; Darius, H.; Desmet, W.; Ebrahimi, R.; Hamon, M.; Rasmussen, L. H.; Rupprecht, H. J. R.; Hoekstra, J.; Mehran, R.; Ohman, E. M.; Acuity, I. (2006). "Bivalirudin for Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (21): 2203–2216. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062437. PMID 17124018.

- ↑ Weitz, J. I.; Bates, S. M. (2002). "Acute coronary syndromes: A focus on thrombin". The Journal of invasive cardiology. 14 Suppl B: 2B–7B. PMID 11967385.

- 1 2 3 Bittl, J. A.; Chaitman, B. R.; Feit, F.; Kimball, W.; Topol, E. J. (2001). "Bivalirudin versus heparin during coronary angioplasty for unstable or postinfarction angina: Final report reanalysis of the Bivalirudin Angioplasty Study". American Heart Journal. 142 (6): 952–959. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.119374. PMID 11717596.

- 1 2 3 Lincoff, A. M.; Bittl, J. A.; Harrington, R. A.; Feit, F.; Kleiman, N. S.; Jackman, J. D.; Sarembock, I. J.; Cohen, D. J.; Spriggs, D.; Ebrahimi, R.; Keren, G.; Carr, J.; Cohen, E. A.; Betriu, A.; Desmet, W.; Kereiakes, D. J.; Rutsch, W.; Wilcox, R. G.; De Feyter, P. J.; Vahanian, A.; Topol, E. J.; Replace-2, I. (2003). "Bivalirudin and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade compared with heparin and planned glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade during percutaneous coronary intervention: REPLACE-2 randomized trial". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 289 (7): 853–863. doi:10.1001/jama.289.7.853. PMID 12588269.

- ↑ Brauser, Deborah (2015-04-13). "BRIGHT in Print: Bivalirudin Bests Heparin for Fewer Bleeding Events During PCI, but Dose Matters". Medscape. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Yaling, Han. "BivaliRudin in Acute Myocardial Infarction vs Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and Heparin :a Randomised Controlled Trial. (BRIGHT)". Shenyang Northern Hospital.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Annex 1 - Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). www.themedicinescompany.com. The Medicines Company UK Ltd. March 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "Angiomax US PI June 2013" (PDF). Angiomax.com.

- ↑ Zamora, Rolando; Forbes, Thomas; Hijazi, Ziyad; Qureshi, Athar; Ringewald, Jeremy; Rome, Jonathan; Vincent, Robert (2009). "Bivalirudin (Angiomax®) As a Procedural Anticoagulant in the Pediatric Population Undergoing Intravascular Procedures for Congenital Heart Disease". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 73 (S1): S8.

- 1 2 Stone, G. W.; Witzenbichler, B.; Guagliumi, G.; Peruga, J. Z.; Brodie, B. R.; Dudek, D.; Kornowski, R.; Hartmann, F.; Gersh, B. J.; Pocock, S. J.; Dangas, G.; Wong, S. C.; Kirtane, A. J.; Parise, H.; Mehran, R.; Horizons-Ami Trial, I. (2008). "Bivalirudin during Primary PCI in Acute Myocardial Infarction". New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (21): 2218–2230. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708191. PMID 18499566.

- ↑ Mehran, R.; Lansky, A. J.; Witzenbichler, B.; Guagliumi, G.; Peruga, J. Z.; Brodie, B. R.; Dudek, D.; Kornowski, R.; Hartmann, F.; Gersh, B. J.; Pocock, S. J.; Wong, S. C.; Nikolsky, E.; Gambone, L.; Vandertie, L.; Parise, H.; Dangas, G. D.; Stone, G. W.; Horizons-Ami Trial, I. (2009). "Bivalirudin in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction (HORIZONS-AMI): 1-year results of a randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 374 (9696): 1149–1159. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61484-7. PMID 19717185.

- ↑ Gregg W. Stone (25 September 2009). HORIZONS- AMI: Two-Year Follow-up from a Prospective, Randomized Trial of Heparin Plus Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors vs. Bivalirudin and Paclitaxel-Eluting vs. Bare-Metal Stents in STEMI. TCT2009 Conference, San Francisco.

- ↑ Kushner, F. G.; Hand, M.; Smith Jr, S. C.; King Sb, S. B.; Anderson, J. L.; Antman, E. M.; Bailey, S. R.; Bates, E. R.; Blankenship, J. C.; Casey Jr, D. E.; Green, L. A.; Hochman, J. S.; Jacobs, A. K.; Krumholz, H. M.; Morrison, D. A.; Ornato, J. P.; Pearle, D. L.; Peterson, E. D.; Sloan, M. A.; Whitlow, P. L.; Williams, D. O. (2009). "2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (Updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (Updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update)". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 54 (23): 2205–2241. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.015. PMID 19942100.

- ↑ Anderson, J. L.; Adams, C. D.; Antman, E. M.; Bridges, C. R.; Califf, R. M.; Casey Jr, D. E.; Chavey We, W. E.; Fesmire, F. M.; Hochman, J. S.; Levin, T. N.; Lincoff, A. M.; Peterson, E. D.; Theroux, P.; Wenger, N. K.; Wright, R. S.; Smith Jr, S. C.; Jacobs, A. K.; Adams, C. D.; Anderson, J. L.; Antman, E. M.; Halperin, J. L.; Hunt, S. A.; Krumholz, H. M.; Kushner, F. G.; Lytle, B. W.; Nishimura, R.; Ornato, J. P.; Page, R. L.; Riegel, B.; American College Of, C. (2007). "ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 50 (7): e1–e157. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. PMID 17692738.

- ↑ Harrington, R. A.; Becker, R. C.; Cannon, C. P.; Gutterman, D.; Lincoff, A. M.; Popma, J. J.; Steg, G.; Guyatt, G. H.; Goodman, S. G.; American College of Chest Physicians (2008). "Antithrombotic Therapy for Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition)". Chest. 133 (6 suppl): 670S–707S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0691. PMID 18574276.

- ↑ Members, A. /T. F.; Albertsson, S.; Avilés, P.; Camici, F. F.; Colombo, P. G.; Hamm, A.; Jørgensen, C.; Marco, E.; Nordrehaug, J.; Ruzyllo, W.; Urban, P.; Stone, G. W.; Wijns, W.; Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology (2005). "Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: the Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology". European Heart Journal. 26 (8): 804–847. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi138. PMID 15769784.

- ↑ Bassand, J. -P.; Bassand, C. W.; Hamm, D.; Ardissino, E.; Boersma, A.; Budaj, F.; Fernández-Avilés, K. A. A.; Fox, D.; Hasdai, E. M.; Ohman, L.; Wallentin, W.; Wijns, A.; Camm, J.; De Caterina, R.; Dean, V.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Kristensen, S. D.; Widimsky, P.; McGregor, K.; Sechtem, U.; Tendera, M.; Hellemans, I.; Gomez, J. L. Z.; Silber, S.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Kristensen, S. D.; Andreotti, F.; Benzer, W.; Bertrand, M. (2007). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology". European Heart Journal. 28 (13): 1598–1660. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. PMID 17569677.

- ↑ Van De Werf, F.; Bax, J.; Betriu, A.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Crea, F.; Falk, V.; Filippatos, G.; Fox, K.; Huber, K.; Kastrati, A.; Rosengren, A.; Steg, P. G.; Tubaro, M.; Verheugt, F.; Weidinger, F.; Weis, M.; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); Vahanian, A.; Camm, J.; De Caterina, R.; Dean, V.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Hellemans, I.; Kristensen, S. D.; McGregor, K.; Sechtem, U.; Silber, S.; Tendera, M.; Widimsky, P. (2008). "Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology:". European Heart Journal. 29 (23): 2909–2945. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. PMID 19004841.