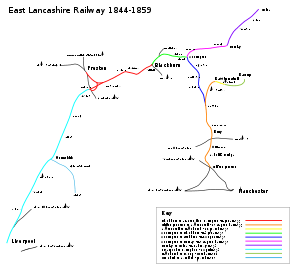

East Lancashire Railway 1844–59

| Industry | Railway company |

|---|---|

| Fate | Amalgamation |

| Successor | Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway |

| Founded | 24 July 1845 |

| Defunct | 13 May 1859 |

| Headquarters | Lancashire |

Key people | John Shae Perring (resident engineer)[1] |

The East Lancashire Railway operated from 1844 to 1859 in the historic county of Lancashire, England. It began as a railway from Clifton via Bury to Rawtenstall, and during its short life grew into a complex network of lines connecting towns and cities including Liverpool, Manchester, Preston and Blackburn.

During a period of rapid growth the company acquired several of its competitors, including the Blackburn and Preston Railway, which it purchased to gain access to Preston. It faced competition from companies such as the North Union Railway, and was involved in a notable stand-off in 1849 with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Following several years of discussions, the East Lancashire Railway was in 1859 amalgamated with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Parts of the network remain in use today, and a section of the original line between Bury and Rawtenstall is now operated as a heritage railway.

History

Manchester and Bolton Railway

In 1830, the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal Company began to promote the construction of a railway along the line of their canal from Salford, to Bolton and Bury.[2] Following an act of parliament to enable them to become a railway company,[2][3] they built their line from Manchester to Bolton, although on a slightly different alignment than was first planned. This was mainly to preserve the canal for the use of mine traffic, which would not have been provided for if the canal had been infilled and replaced by a railway.[4][5] A new Act had been required for the new alignment,[6] but due mainly to the objections of the company's engineer, the connection to Bury was never built, as it would have required a 1,100-yard (1,000 m) tunnel on a gradient of 1 in 100, at the time a difficult and expensive proposition.[7] The new railway therefore became known as the Manchester and Bolton Railway.

Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway

On 14 September 1843, a group of local businessmen including John Grundy, Thomas Wrigley and John Robinson Kay met at a public house in Bury to discuss the creation of a railway connection for the Bury and the Rossendale districts. Their proposed railway offered better facilities than those also proposed by the Manchester and Leeds Railway (M&LR), whose planned connection at Bury would be made with their Heywood branch line from Castleton.[8] The Manchester, Bury and Rossendale Railway Company (MB&RR) was thus created, its purpose to build a railway from Bury to Clifton, where it would connect to the Manchester and Bolton Railway. The company also promoted the idea of extending the line northwards to Rawtenstall.[7] On 4 July 1844 their private bill[9][10][11] was granted Royal Assent. The Act authorised the company to raise £300,000, and also to borrow £100,000 (£27 million and £9 million respectively in 2016).[11][12]

The land between Clifton and Bury, partly owned by the Earl of Derby, John Robinson Kay, William Grant and others, was mostly "waste, woodland, pasture or reservoirs, except at Brookbottoms where arable land was avoided by the tunnel".[7] Strong financial support was offered to the MB&RR by local businesses, who were unhappy with the idea of the M&LR building their own railway.[8] The Manchester and Leeds District Board of Trade produced a report in 1845 which gave their backing to the M&LR[13] and the line was sanctioned in 1846, however the MB&RR project was unaffected by this connection.[8]

Manchester contractors Pauling & Henfry, who tendered £167,529 (£15.1 million in 2016),[12] were in May 1844 awarded two contracts to build the Clifton to Bury and Bury to Rawtenstall sections of the new railway.[14] The work was sub-let to smaller contractors and began quickly; in July 1844 the Manchester Guardian wrote a favourable report on the works. However, a shortage of workers in 1845 (reflecting the amount of railway construction underway at that time) meant that some men were asked to work on Sundays, resulting in some being charged with breaking the Sabbath. Further difficulties prompted the dismissal of the original contractors, their place being taken by John Waring.[14]

The railway ran north from Clifton through a cutting at Outwood. This required the removal of about 600,000 cubic yards (460,000 m3) of earth.[15] It then passed north-east through Radcliffe Bridge and Withins station,[16] and from there into Bury Bolton street station. From Bury, it ran through Summerseat, Ramsbottom, Stubbins and finally to Rawtenstall. The railway climbed a constant gradient, across a mixture of viaducts, tunnels, cuttings and embankments, one of which, the mile–long section from Ramsbottom to Stubbins, was substantial.[17] The extant Clifton Viaduct was built to cross the River Irwell, which flowed 80 feet (24 m) below, and also the Manchester Bolton & Bury Canal. Its largest span is 96 feet (29 m) wide.[10]

Expansion

By 1844, the Blackburn and Preston Railway (B&PR), who shared a viaduct across the River Ribble with the North Union Railway (NUR), were planning a railway from Blackburn to Farington.[11][18] Following an 1845 act[11][19] the B&PR was absorbed by the MB&RR on 3 August 1846.[10] The B&PR's Act of Parliament also allowed for a connection with the proposed Blackburn, Burnley, Accrington and Colne Extension Railway (BBA&CER), which would run from Stubbins Junction to Accrington, providing a direct link between Blackburn and Colne. A second BBA&CER act allowed it to lease or sell itself to the MB&RR, and so in 1845 the two companies joined. The MB&RR later that year changed its name to the East Lancashire Railway (ELR).[8]

The following year, the ELR acquired the Liverpool, Ormskirk and Preston Railway (LO&PR),[11][20] which gave it direct access to Liverpool Docks. The LO&PR's line would run from a junction with the Liverpool and Bury Railway at Walton-on-the-Hill to a junction with the B&PR. The enabling act also allowed the LO&PR to build further branch lines, and the ELR obtained further acts including one which allowed it to build a connection to Preston.[8] Following the acquisition on 3 August 1846,[21] a disagreement ensued over traffic priorities and arrangements for the ELR at the NUR's station in Preston. The ELR proposed a new station and a separate line with a new crossing of the Ribble, but this proved controversial; Preston Corporation petitioned against the proposed line, producing a series of witnesses who attested to the damage they presumed would be caused by the embankment necessary for the scheme to proceed. Several members of the corporation were also shareholders of the rival Fleetwood, Preston and West Riding Junction Railway, and the petition's proposer was brother-in-law to a director of the rival Manchester and Leeds Railway. In the end the ELR won its bid, but had to landscape its embankment (which later became the dividing line between Avenham and Miller Parks), make an ornamental arch for carriages and pedestrians crossing under the railway, and build a footbridge on the river viaduct.[22]

Meanwhile, the former MB&RR line from Clifton to Rawtenstall was inaugurated on Friday 25 September 1846. Surveyed two days earlier by the Inspector-General of railways, Charles Pasley,[23] who was reportedly satisfied with the project,[14] upwards of 1,000 invitations were delivered to local people, shareholders and other interested parties. They gathered at the new Hunts Bank station in Manchester. Leaving Manchester, the train stopped near Philips Park to collect chairman John Hodges, before continuing to Radcliffe Bridge to collect more passengers. Large crowds were gathered along the course of the railway. In Bury, the train was extended to about 30 carriages and three engines, and more passengers were collected before the train finished its journey in Rawtenstall. Passengers were provided with a large meal in a closed-off section of a power-loom shed owned by John Robinson Kay. They listened to several celebratory speeches, before re-embarking the train to head home.[15] The railway was opened to the general public on the following Monday.[24]

In November 1846 the company submitted proposals for a new line from Buckley Wells (south of Bury) through Whitefield and Prestwich, to a new terminus at Victoria Station. The plan did not progress any further than the initial planning stages; Whitefield and Prestwich eventually got their own railway stations in 1879.[25]

In two years the ELR grew from a company authorised to build 14 miles (23 km) of railway into one with the authority to build 50 miles (80 km) of railway.[8] In February 1848 with 24 miles (39 km) of track open, the company reported for the week ending 5 February 1848 an annual income of £553 18s 8d (£50,000 in 2016)[12] for passengers and parcels, and £498 10s 4d for freight (£45,000 in 2016)[12] – almost double the previous year's income.[26] By March 1848 the line between Rawtenstall and Newchurch was complete, followed in June by the Blackburn to Accrington connection (5.25 miles (8.45 km)),[27] and, in August, the Stubbins junction to Accrington section. The line was extended east to Burnley (5.5 miles (8.9 km))[27] by September 1848, and, in February 1849, from Burnley to Colne, where it made an end-on junction with the Leeds and Bradford Extension Railway, providing the ELR with a connection to Bradford and Leeds.

The LO&PR line to Lostock Hall (26 miles (42 km))[27] was completed on 2 April 1849,[28] and the (3 miles (4.8 km))[27] extension into Preston station opened on 2 September 1850.[29] The line ran into new platforms built on the east side of the NUR's station, which were managed and staffed by the ELR, and which had their own booking hall and entrance. The new platforms were effectively a separate station.[30][31]

More lines followed with a connection between Newchurch and Bacup by October 1852, and the Ormskirk to Rainford Skelmersdale Branch in March 1858.[32] A three-mile long line to Tottington opened in 1882 from a junction with the original MB&BR line. It was electrified in 1913 before reverting to steam in 1951. It closed to passengers in 1952 and goods in 1963 and has since been reclaimed as a walkway.[33]

Clifton Junction

In 1846, the Manchester and Bolton Railway (whose line the ELR used to gain access to Manchester) was taken over by the Manchester and Leeds Railway,[34][35] which, the following year, became part of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR).[36] The ELR's expansion and the opening of new routes—including an alternative route between Manchester and Leeds—had caused a degree of consternation at the L&YR, but the two companies initially managed to work together successfully.

After about three years a dispute flared up over the collection of tolls for the ELR's use of the line. The ELR had become accustomed to running their trains on to the L&YR line and then later declaring of the number of passengers liable for a toll but, in March 1849, the L&YR insisted that ELR trains stop at Clifton so that passenger numbers and tickets could be checked by their own employees. The ELR accused the L&YR of trying to impede their traffic, particularly as they had recently gained a connection to Bradford, in competition with the L&YR. They stated that the L&YR had access to their accounts, and to the returns made by their staff.[37]

On the morning of 12 March 1849, despite the presence of police from Bury and Pendleton, the L&YR placed a large baulk of timber across the ELR's line at Clifton Junction, effectively blocking it. Employees from both companies arrived at the scene, and a large crowd gathered to watch events unfold. The L&YR also pulled a train past the junction, blocking the up line to the city. Its engine was pointed south-east toward Manchester, available to any ELR passengers who wished to continue their journey. An ELR train arrived from Bury, and stopped. L&YR employees attempted to take tickets from the ELR's passengers, but were refused, as the ELR had already taken tickets at their Ringley Road station. ELR employees then removed the baulk of timber, and in an effort to push the L&YR train out of the way, drove their train forward. The L&YR had anticipated this, and moved another engine (taken from a L&YR train from Manchester) to the front of their Manchester-bound train. The ELR then blocked the L&YR down line with another of their trains, laden with stone, moving it to a position directly abreast of the L&YR train. The line remained completely blocked until about mid-day, with a queue of trains from both companies, and from the Blackburn and Darwen Railway, building up on each side of the blockage. The situation was eventually defused when the L&YR withdrew their train.[37]

The General Manager of the ELR, Richard Hacking, wrote to The Times newspaper expressing his annoyance at the L&YR's tactics. He claimed to have received a letter from the company sent on 9 March 1849 informing him of proposed changes to operational procedures resulting from a near-collision at Clifton Junction. The first change was that ELR trains would at all times give way to L&YR trains on the Manchester and Bolton line; a stop signal was to be placed 400 yards (370 m) along the ELR line from the junction, to be activated whenever a L&YR train was in sight. The second change was that "for the safety of the public"[38] all ELR trains would be required to stop before the points at the junction, where all passenger tickets to Manchester would be collected by L&YR employees. A daily return would be required of all passengers and other freight booked from Salford "for the purpose of keeping regularly and balancing punctually the accounts of the two companies".[38] Hacking claimed to have replied stating that the near-collision had occurred because the L&YR's engine driver had ignored a signal at Clifton Junction, and that the ELR would not accept the changes requested by the L&YR. The ELR refused to supply tickets at any point, although they considered it reasonable to supply more information on their traffic using the L&YR line.[38]

Hacking stated that he had received a letter from the L&YR porter at Clifton requesting that all ELR trains stop at Clifton Junction so that tickets could be collected by L&YR staff, and that all ELR goods trains would have to supply invoices at the junction. In his letter he concluded that the purpose of the L&YR's demands was to impede the flow of ELR traffic to Manchester and onwards to Yorkshire.[38]

Hacking's account of the events of 12 March is similar to that reported by The Times. He claims to have travelled to Clifton to witness an L&YR clerk being prevented from collecting tickets, and to have then continued on another train to Manchester. On his arrival there, he saw L&YR employees ready to pull up the rails to the ELR platform, although the rails were left intact. He then mentions returning to Clifton after hearing that L&YR employees had recently left for the station. He blamed the Managing Director of the L&YR, Captain Law, and Mr Blackmore, superintendent of the Bolton line, for ordering theline to be blocked with the baulk of timber. Hacking also mentions an approaching up-train from Bolton, which on encountering the blockage apparently moved across to the down line to bypass it – in the face of oncoming traffic. Expressing his shock, he claims to have ordered the ELR's stone train onto the down line, changing the signals accordingly. Hacking's account ends by claiming that Blackmore ordered the L&YR train to move, effectively resolving the dispute.[38]

The matter was so serious that it was raised in the House of Commons.[39] It was eventually settled in court, with the ELR thereon making a pro rata payment according to the distance travelled on each railway. The court also found in favour of the L&YR who had argued that the original agreement to share the line did not extend to a vastly extended ELR network. The amount of compensation to the L&YR was left at the discretion of both companies.[40]

Relations between the two companies were, therefore, not entirely amicable. In 1853 the ELR made further proposals for a new line from Clifton to Salford, roughly parallel to the L&YR line, however in 1854 an agreement between the two companies meant that the Clifton Junction to Salford line was vested jointly in both companies.[41] Amalgamation had been discussed since the early 1850s and in 1859, by an act of parliament,[42] the ELR was absorbed by the L&YR.[32]

Closure and legacy

Following the Beeching Axe parts of the ELR's network were closed. The original MB&RR line between Clifton Junction and Bury closed in 1966 (although Radcliffe Bridge station was closed in 1958),[43] but the line between Bury and Rawtenstall continued to serve passengers until 1972 and freight until 1980. This section is now used by the East Lancashire Railway, a modern heritage railway opened in 1987.[44] The trackbed between Clifton and Radcliffe now forms a part of the Irwell Sculpture Trail.[45] The connection from Stubbins to Accrington was closed in 1966.[46] The ELR line across the Ribble between Preston and Bamber Bridge was closed to passengers in 1968, and to goods four years later. The East Lancashire platforms 10–13 were demolished along with Butler Street Goods Yard.[47] The line between Preston and Colne survives as the East Lancashire Line, operated by Northern.[48] The Skelmersdale Branch was closed to passengers in 1956 and to all traffic seven years later,[49] however a proposal exists to reopen the line as far as Skelmersdale.[50] Services between Liverpool and Ormskirk are now operated by Merseyrail.[51]

Locomotives

The ELR used a range of locomotives. One of its earliest orders was for twelve Long Boiler 2-2-2s from Fenton, Craven and Company (at least one of these was used on the inauguration of the railway[15]), but dissatisfied with the locomotives they accepted only four,. Four were diverted to the Leeds, Dewsbury and Manchester Railway, and two to the Eastern Counties Railway. In 1848, the ELR's four 2-2-2s were rebuilt as 2-4-0s by R and W Hawthorn. In about 1858, they were again rebuilt as 0-6-0s by Sylvester Lees. Richard Walker, a director of the ELR between 1838 and 1854, was the supplier of about twenty locomotives to the company, including, in the 1850s, four 2-4-0s and several 0-6-0s.[52]

Walker, Richard & Brother supplied four 2-2-2 locomotives, Medusa, Hecate, Diomed and Lynx. All were later rebuilt as a 2-4-0 tank engine. In 1847, two 0-4-2s were supplied by R and W Hawthorn, rebuilt in 1868 as 2-4-0s. In 1845 the MB&RR ordered four 0-6-0s from the Haigh Foundry, and a fifth engine from Fenton, Craven and Company. Another engine was built by Haigh in 1848.[52]

The largest ELR class was a series of outside-frame 2-4-0s with 15 in × 20 in (38 cm × 51 cm) cylinders and 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) driving wheels. Some may have originated as 2-2-2s, and some were later rebuilt as 2-4-0 tank engines. One was rebuilt as a 2-4-0 saddle tank engine. These were among the last locomotives to be built in Bury. Other manufacturers to supply the ELR were Sharp, Roberts and Company, Stothert, Slaughter and Company, and Beyer, Peacock and Company. The ELR livery for passenger locomotives was dark green with red brown frames, and polished domes and safety valves.[52]

Infrastructure

Station buildings

Station buildings generally followed one of three designs. The principal stations at Bury and Accrington were based on the same design by a Manchester-based firm of architects. Most of the other stations were designed by the company's resident engineer. They were stone-built and consisted of a station master's room, adjoining a seated waiting area, a ladies waiting room and the booking office. The third and cheapest design followed the standard design but utilised brick and timber as materials. The platform was normally roofed.[10]

Signals

Track signals were based on two designs—station signals on posts, each post with two moveable arms—and portable signals; flags were used by day, and coloured lanterns at night. The signals on posts were patented semaphore designs from J Stevens & Son. Each post had two arms—linked by chain to a foot control at the base—which were used to alert drivers on both the up and down lines. Each foot control was held in place by a hook on the post. An arm set at an angle would indicate that the train should approach slowly, before stopping at the station. The same arm set vertically (and out of sight) would indicate that the train could pass through without stopping. The posts were also illuminated to allow use at night. Signals at Accrington station were more complex, linked to the station building with wires, and by default set at 'stop' when released. The coloured lanterns used as portable signals were painted red on one side (stop), green on another (go slowly), and clear on the third (proceed).[10]

Rails

The line was standard gauge and most sections used rails in 15-foot (4.6 m) lengths, each weighing 75 lb/yard (31.1 kg/m), fixed to wooden sleepers 9 feet (2.7 m) long and 3 feet (0.91 m) apart.[10]

Accidents

In the early history of the railways accidents were not uncommon, and the ELR was no exception. Several incidents were reported in The Times. During Whitsuntide 1849, a passenger train was in a rear-end collision with an excursion train near Burnley, Lancashire. Despite efforts to protect the rear of the passenger train, another excursion train was in a rear-end collision with it.[53] In January 1850, three people died when a luggage train ran into a passenger train at Maghull railway station.[54] A serious accident occurred at Clifton Junction on 19 October 1851 when a passenger train derailed passing the points on the junction, injuring several passengers, some seriously.[55] In September 1866 a man died after jumping from the train from Blackburn.[56] A non-fatal collision occurred at Lostock Hall railway station in November 1876.[57]

Inclement weather was also a problem; in January 1867 trains were delayed for several hours at Hoghton due to snow on the line,[58] and on 30 January 1877 a heavy storm blew the roof completely away from Preston railway station.[59]

References

Notes

- ↑ Boase, G. C.; Cox, R. C. (2004), Perring, John Shae (1813–1869) (Registration required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21981, retrieved 13 April 2009

- 1 2 Hadfield 1970, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Paget-Tomlinson 2006, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Hadfield 1970, p. 257.

- ↑ Canal at Pendleton on 19 November 1966, Manchester Libraries, retrieved 30 June 2008

- ↑ Expanded index and summary of Backtrack Volume 17, www.steamindex.com, retrieved 30 June 2008

- 1 2 3 Wells 1995, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Broadbridge 2006, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ 7 & 8 Vict. c.60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harrison and Sale's Guide to the East Lancashire Railway, Bury Local Library: Harrison and Sale, 1 Spring Gardens, 1849

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scrivenor 1849, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Parliamentary papers - Report of the Board of Trade on the Manchester and Leeds District, HMSO, 1849, p. 17, retrieved 13 April 2009

- 1 2 3 4 Wells 1995, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 3 Opening of the East Lancashire Railway, yesterday, The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser, 26 September 1846

- ↑ Withins station closed in 1851 - Wells (1995) p. 10.

- ↑ Hyde & Selby 1991, pp. 5, 10.

- ↑ 7 & 8 Vict. c.34

- ↑ 9 & 10 Vict. c.302

- ↑ 9 & 10 Vict. c. 381

- ↑ Greville & Holt 1960a, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Lewis 2001, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Vetch, R. H.; Sweetman, John (2004), Pasley, Sir Charles William (1780–1861) (Registration required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21499, retrieved 13 April 2009

- ↑ Wells 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ Townley et al. 1995, p. 24.

- ↑ East Lancashire Railway, G (19783), The Times, 11 February 1848, p. 6, retrieved 14 April 2009

- 1 2 3 4 Scrivenor 1849, p. 432.

- ↑ Opening of the Liverpool, Ormskirk and Preston Railway, E (20140), The Times, 3 April 1849, p. 8, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ Greville & Holt 1960b, p. 197.

- ↑ Greville & Holt 1960a, p. 101.

- ↑ Suggitt 2003, p. 59.

- 1 2 Broadbridge 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Hyde & Selby 1991, p. 6.

- ↑ 9 & 10 Vict. c.378

- ↑ Scrivenor 1849, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Awdry 1990, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 Extraordinary Scene At A Railway Junction, F (20124), The Times, 15 March 1849, p. 8, retrieved 14 April 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hacking, Richard (15 March 1849), Letters to the Editor - Obstruction of East Lancashire Railway, F (20124), The Times, p. 6, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ House Of Commons, A (20126), The Times, 17 March 1849, p. 3, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ Bennett & Smith 1852, pp. 573–574.

- ↑ Townley et al. 1995, p. 25.

- ↑ Rickards 1859, p. 293.

- ↑ Wells 1995, p. 114.

- ↑ A History of the East Lancashire Railway, east-lancs-rly.co.uk, retrieved 5 April 2009

- ↑ The Irwell Sculpture Trail (PDF), irwellsculpturetrail.co.uk, archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009, retrieved 26 April 2009

- ↑ Butt 1995, p. 118

- ↑ Suggitt 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ Northern Rail Network Map, northernrail.org, retrieved 26 April 2009

- ↑ Marshall, J. (1981) Forgotten Railways North-West England, David & Charles (Publishers) Ltd, Newton Abbott. ISBN 0-7153-8003-6, p.93

- ↑ Merseyside Route Utilisation Strategy (PDF), networkrail.co.uk, March 2009, retrieved 26 April 2009

- ↑ Merseyrail Network Map, merseytravel.gov.uk, archived from the original on June 21, 2008, retrieved 26 April 2009

- 1 2 3 Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway locomotives, steamindex.com, 28 October 2006, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ Hall 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ "The Late Accident On The East Lancashire", The Times, F (20380), p. 4, 8 January 1850, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ "Serious Accident On The East Lancashire", The Times, D (20939), p. 5, 22 October 1851, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ "Fatal Accident", The Times, B (25596), p. 10, 6 September 1866, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ "Railway Collision", The Times, F (28785), p. 9, 13 November 1876, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ "The Late Snow Storm", The Times, D (25704), p. 12, 10 January 1867, retrieved 14 April 2009

- ↑ "The Gale. Meteorological Reports", The Times, D (28853), p. 6, 31 January 1877, retrieved 14 April 2009

Bibliography

- Awdry, C (1990), Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies, Wellingborough: Stephens, ISBN 1-85260-049-7

- Bennett, Edmund H.; Smith, Chauncey (Edrs) (1852), English Reports in Law and Equity, 8, Boston: Little, Brown and Company

- Biddle, G. (1989), The Railways Around Preston - A Historical Review, Scenes From The Past, 6, Foxline Publishing, ISBN 1-870119-05-3

- Broadbridge, Seymour (2006), Studies in railway expansion and the capital market in England 1825-1873, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-38216-5

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995), The Directory of Railway Stations, Patrick Stephens Ltd, ISBN 1-85260-508-1

- Hall, Stanley (1990). The Railway Detectives. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0 7110 1929 0.

- Greville, M. D.; Holt, G. O. (February 1960), "Railway Development in Preston—1" (PDF), The Railway Magazine, vol. 106 no. 706, pp. 94–101, 125

- Greville, M. D.; Holt, G. O. (March 1960), "Railway Development in Preston—2" (PDF), The Railway Magazine, vol. 106 no. 707, pp. 197–203

- Hadfield, Charles; Biddle, Gordon (1970), The canals of northwest england volume 2, Newton Abbot: David and Charles limited, ISBN 0-7153-4992-9

- Hyde, John; Selby, Anne (March 1991), East Lancashire Railway Guide Souvenir Special, Armstrong Printing and Graphics

- Lewis, Brian (2001), The middlemost and the milltowns, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4174-3

- Littleworth, C. (2002), Signal Boxes on Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Lines - North-East Lancashire, Signalling Record Society, ISBN 1-873228-21-X

- Littleworth, C. (2014), Signal Boxes on Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Lines - North and West of Manchester: Part Two, Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Society, ISBN 978-0-9559467-6-9

- Paget-Tomlinson, Edward (2006), The Illustrated History of Canal & River Navigations 3rd edition, Ashbourne, UK: Landmark Publishing Ltd, ISBN 1-84306-207-0

- Rickards, George Kettilby (1859), The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1807–1868/69), His Majesty's statute and law printers

- Rush, R.W. (1983), The East Lancashire Railway, The Oakwood Press, ISBN 0-85361-295-1

- Scrivenor, Harry (1849), The Railways of the United Kingdom, Smith, Elder, and co.

- Suggitt, G. (2003), Lost Railways of Lancashire, Countryside Books, Newbury, ISBN 1-85306-801-2

- Townley, C. H. A.; Appleton, C. A.; Smith, F. D.; Peden, J. A. (1995), The Industrial Railways of Bolton, Bury and the Manchester Coalfield, Runpast Publishing, ISBN 1-870754-32-8

- Wells, Jeffrey (1995), An Illustrated Historical Survey of the Railways in and Around Bury, Challenger Publications, ISBN 1-899624-29-5

External links