Blackwell, Oklahoma

| Blackwell, Oklahoma | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Looking east along West Doolin Avenue | |

|

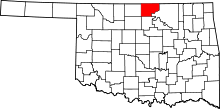

Location of Blackwell in Oklahoma. | |

| Coordinates: 36°48′6″N 97°17′23″W / 36.80167°N 97.28972°WCoordinates: 36°48′6″N 97°17′23″W / 36.80167°N 97.28972°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oklahoma |

| County | Kay |

| Government | |

| • City Manager | Thomas "Chip" Outhier[1] |

| • Mayor | Max Wirtz |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.5 sq mi (14.1 km2) |

| • Land | 5.4 sq mi (14.1 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,014 ft (309 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,092 |

| • Density | 1,300/sq mi (500/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 74631 |

| Area code(s) | 580 |

| FIPS code | 40-06600 [2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1090237 [3] |

| Website | City Website |

Blackwell is a city in Kay County, Oklahoma, United States, located at the intersection of U.S. Highway 177 and State Highway 11 along Interstate 35. The population was 7,092 at the 2010 census. Blackwell was established following the September 16, 1893 Cherokee Outlet land run by A. J. Blackwell.[4] Blackwell has an agricultural and fossil fuel based economy.

History

Founding

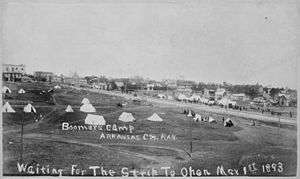

Blackwell came into existence during the Cherokee Outlet Opening on September 16, 1893 in the run known as the Cherokee Strip Land Run. The town is named for A. J. Blackwell, who was the dominant force in its founding. A post office was established on December 1, 1893. Due to a struggle for regional prominence between Blackwell and nearby Parker, the post office was named Parker from April 2, 1894, to February 4, 1895. After the latter date, the name reverted to Blackwell.[5]

Andrew Blackwell had settled in the area in 1882,[6] having married the former Rosa Vaught who was of Cherokee descent, he was eligible to found the city. Blackwell served as Justice of the Peace and Mayor of Blackwell.[6]

Blackwell's first school opened in September 1893 in a small, frame building with fifty-two students in attendance. A gradual enrollment increase created a need for ten teachers by 1899.[5]

Blackwell has a reputation as a sundown town,[7][8] having kept out African Americans through violent expulsion and the display of a sign warning them to leave town by sunset. Blackwell's expulsion of its African-American residents around 1893[9] is described in the 1967 book From Slavery to Freedom by John Hope Franklin.

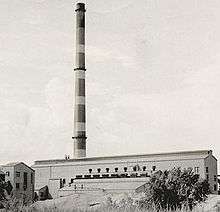

Zinc Smelter

The Blackwell Zinc Company smelter first began operations in 1917.[4] In 1974, the 80-acre[10] Blackwell Zinc Smelter facility ceased operations.[11] At the time, it was the city's largest employer, employing 800 people in 1972, and over 1,000 at its peak.[4] It also was one of the largest zinc smelter facilities in the United States.[12] After its closure the land and was donated to the Blackwell Industrial Authority (BIA).[13] Soil from the land was repurposed throughout the city, leading to widespread contamination of air and water, including the Chikaskia River.[10]

Additionally, one of the plant's two Corliss stationary steam engines was moved to Pawnee Oklahoma and preserved. This engine is run for viewing by the public on the first weekend of May.

The Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality has been overseeing remediation of contamination at the industrial park, groundwater, and soil throughout parts of the city since 1992.[14] Phelps Dodge Corporation, a subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc, has owned the site since 1999.[15] On October 15, 2009 the City of Blackwell filed suit against Freeport-McMoRan calling the contamination a nuisance, and alleging that 58 million pounds of toxic waste remained in the city, causing illness within its 7,200 residents.[10][16] Following several changes of venue between Federal court and Kay County courts, the City of Blackwell and Freeport settled for 54-million dollars on February 4, 2010.[17][18]

1955 F5 Tornado

Blackwell was a victim of the 1955 Great Plains tornado outbreak, a deadly tornado outbreak that struck the southern and central U.S Great Plains States on May 25–26, 1955. It produced at least 46 tornadoes across seven states including two F5 tornadoes in Blackwell, Oklahoma, and Udall, Kansas. The outbreak killed 102 from three tornadoes while injuring hundreds more. Unusual electromagnetic activity was observed, including St. Elmo's fire.[19]

The Blackwell tornado formed in Noble County at around 9:00 PM CDT before crossing through the eastern portions of the Kay County town of Blackwell as an F5 wedge tornado. Then about 400 yd (0.23 mi) wide (Grazulis 1991), It claimed the lives of 20 people in Blackwell and injured over 200 before crossing into and dissipating over Cowley County, Kansas. Along with destroying nearly 200 homes,[20] the tornado demolished two of the town's main employers, the Acme Foundry and the Hazel Atlas Glass plant. 400 homes were destroyed or swept away, and 500 other homes were damaged.[20] 60 businesses were also destroyed and the local hospital sustained major damage. Most of the western half of the town was spared the worst of the damage.[20]

Geography

Blackwell is located at 36°48′6″N 97°17′23″W / 36.80167°N 97.28972°W (36.801764, -97.289856),[21] along the Chikaskia River and to the east of Interstate 35. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.5 square miles (14 km2), of which, 5.4 square miles (14 km2) of it is land and 0.18% is water.

Climate

In May 1906, an L5 meteorite fell, landing in Blackwell, Oklahoma. On May 25, 1955, a deadly F5 tornado, part of the 1955 Great Plains tornado outbreak, struck Blackwell at approximately 9:30 pm and cut a swath of destruction through the northeastern portion of the city, roughly centered in the neighborhoods surrounding Riverside Park. 20 residents died and 250 were injured. The tornado outbreak included another F5 tornado that struck Udall, Kansas killing 82 people and injuring 270.[22] The outbreak spawned 19 tornadoes across Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas alone.[23][24]

| Climate data for Blackwell, Oklahoma | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 43.6 (6.4) |

49.5 (9.7) |

60.2 (15.7) |

71 (22) |

79.4 (26.3) |

89.6 (32) |

95.7 (35.4) |

94 (34) |

84.5 (29.2) |

73.4 (23) |

58.2 (14.6) |

46.7 (8.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.2 (−5.4) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

35.9 (2.2) |

46.4 (8) |

55.5 (13.1) |

64.8 (18.2) |

69.5 (20.8) |

68.2 (20.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

49.1 (9.5) |

36.8 (2.7) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

46.9 (8.3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.9 (23) |

1.1 (28) |

2.4 (61) |

3 (80) |

4.7 (119) |

3.9 (99) |

3.1 (79) |

3.2 (81) |

4.1 (104) |

2.7 (69) |

2.3 (58) |

1.4 (36) |

32.8 (833) |

| Source: Weatherbase.com [25] | |||||||||||||

Schools

Blackwell Public Schools has four schools, including an early childhood center, an elementary school, a middle school and a high school. For the 2011-2012 school year, there were approximately 1500 students enrolled.[26]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 2,283 | — | |

| 1910 | 3,266 | 43.1% | |

| 1920 | 7,174 | 119.7% | |

| 1930 | 9,521 | 32.7% | |

| 1940 | 8,537 | −10.3% | |

| 1950 | 9,199 | 7.8% | |

| 1960 | 9,588 | 4.2% | |

| 1970 | 8,645 | −9.8% | |

| 1980 | 8,400 | −2.8% | |

| 1990 | 7,538 | −10.3% | |

| 2000 | 7,668 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 7,092 | −7.5% | |

| Est. 2015 | 6,875 | [27] | −3.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 7,668 people, 3,064 households, and 2,086 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,407.3 people per square mile (543.2/km²). There were 3,527 housing units at an average density of 647.3 per square mile (249.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 87.26% White, 4.13% Native American, 0.47% Asian, 0.13% African American, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 3.17% from other races, and 4.83% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.91% of the population.

There were 3,064 households out of which 32.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.1% were married couples living together, 9.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.9% were non-families. 28.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city the population was spread out with 27.0% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 18.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females there were 92.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $25,835, and the median income for a family was $31,540. Males had a median income of $25,202 versus $16,704 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,558. About 13.1% of families and 17.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.4% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Parks, museums, and cultural events

The Top of Oklahoma Historical Society Museum is located in the Electric Park Pavilion and displays artifacts from the land run, antiques, and local history.[28][29] Blackwell hosts the Kay County Free Fair in September. Blackwell is served by 5 major parks including Riverside, Bagby, Rogers, Memorial, and Legion parks. Blackwell has 1 major and 2 minor public pools. Blackwell is also home to a brick WPA armory which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[30]

Government

Blackwell is a Home Rule Charter City, which is governed by Council-City Manager form of government. The current City Manager is Thomas "Chip" Outhier.[1] The City Council consists of T.J. Greenfield, Tom Beliel, Jon Webb and Richard Braden, with Mayor's position currently held by Max Wirtz. The Chief of Police is Dewayne Wood and the Fire Chief is Dirk Seabridge.

Education

The Blackwell School District consists of Blackwell Middle School and Blackwell High School, as well as Huston, Northside, Parkside, and Washington Elementary Schools, which are all listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The school mascot in the Maroon's Historically, Oklahoma Baptist College served the city's higher education needs between 1901 and 1913.[4]

Media

Blackwell's local paper is the Blackwell Journal-Tribune, Radio station KOKB 1580 AM broadcasts sports.

Infrastructure

Blackwell has a full-service city government, that includes, electricity, sewage and police and fire services. The police department has 17 full-time officers, and operates 24 hours per day. The Blackwell Fire Department is a full-time fire department, and also provides ambulance service to Blackwell and the surrounding communities.

Transportation

Blackwell is home to the Blackwell-Tonkawa Municipal Airport (ICAO: KBKN, FAA LID: BKN, formerly 4O3) with neighboring Tonkawa, Oklahoma. Historically, Blackwell was home to the Blackwell, Enid and Southwestern Railway.

Healthcare

Blackwell and the surrounding communities are served by Alliance Health Blackwell, a 53-bed facility with 24-hour emergency services and Heli-Pad.

Notable people

- Joe Allbaugh, Former FEMA Director, former Interim City Manager

- Author Jamie McGuire, Author Providence, Beautiful Disaster, Happenstance.

- Jack Brisco, professional wrestler; former National Wrestling Alliance World Heavyweight Champion, inducted in the WWE Hall of Fame in 2008.

- Jerry Brisco, professional wrestler and longtime employee of World Wrestling Entertainment, Also a WWE Hall of Famer, alongside his brother, Jack Brisco.

- Stephen Aloysius Leven, prelate of the Roman Catholic Church.

- William J. McDaniel, retired United States Navy Rear Admiral[31]

- Brad Penny, Major League Baseball pitcher.

- Jim Reese, former member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives and commissioner of the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture

- Paul G. Risser, former president of several colleges and the chancellor of the Oklahoma State System of Higher Education

- Natalie Shirley, former Secretary of Commerce and Tourism and current President of OSU-OKC

- Aaron Ross Flood,Silver Olympic medalist in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin in freestyle bantamweight competition.

See also

References

- 1 2 http://www.cityofblackwell.com

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson, Linda D.Blackwell, Oklahoma Oklahoma Historical Society

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture Archived December 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Blackwell, Andrew Jackson," Herringshaw's Encyclopedia of American Biography of the Nineteenth Century. Chicago, IL, USA: American Publishers Association, p 117, 1902.

- ↑

- ↑ Loewen, James W. Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.'

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture

- 1 2 3 Welch, Judy, "Oklahoma town suing over contamination", News Cow, April 17, 2008

- ↑ Blackwell Zinc Co. Operational History Report, United States Environmental Protection Agency

- ↑ City of Blackwell, Oklahoma Receives Major Settlement in Environmental Case

- ↑ "Warranty Deed" December 30, 1974

- ↑ Fact Sheet: Blackwell Zinc Smelter Site In Blackwell Oklahoma Archived September 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, June 2007

- ↑ "Lawsuit claims Blackwell polluted from old zinc smelter" April 14, 2008

- ↑ CJ200915 City of Blackwell vs. Freeport

- ↑ Rowen, Sharon, "Public Hearing Held On Blackwell Lawsuit Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.", The Ponca City News, February 19, 2010

- ↑ Settlement Agreement

- ↑ Storm Electricity Aspects of the Blackwell/Udall Storm of 25 May 1955 - Don Burgess, University of Oklahoma (CIMMS)

- 1 2 3 Grazulis, Thomas P (July 1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680-1991. St. Johnsbury, VT: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/wxevents/19550525/

- ↑ Oklahoma Tornado Table

- ↑ KWTV 9 1956 TV Special about Blackwell OK tornado Archived July 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Historical Weather for Blackwell, Oklahoma, United States".

- ↑ "Blackwell Public Schools". Blackwell Public Schools. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ http://www.travelok.com/listings/view.profile/id.8116

- ↑ http://www.ocgi.okstate.edu/shpo/nhrpdfs/76001563.pdf

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- ↑ "OSU Hall of Fame to Induct Zink", Tulsa World, March 4, 1994. Accessed June 20, 2015.

External links

- City Of Blackwell

- Blackwell Chamber of Commerce

- Blackwell Uncovered The only place you will uncover the truth about Blackwell!

- Blackwell Journal-Tribune, the local newspaper

- Blackwell Community Outreach

- City-Data.com - Blackwell

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Blackwell

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory