Union of Brest

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Liturgy and worship |

|

The Union of Brest, or Union of Brześć, was the 1595-96 decision of the Ruthenian Church of Rus', the "Metropolia of Kiev-Halych and all Rus'", to break relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church and to enter into communion with, and place itself under the authority of, the Pope of Rome.

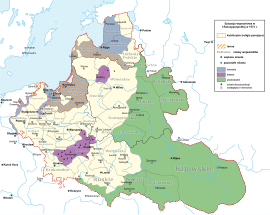

The union

At the time, this church included most Belarusians who lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The hierarchs of the Kievan church gathered in synod in the city of Brest composed 33 articles of Union, which were accepted by the Pope of Rome. At first widely successful, within several decades it had lost much of its initial support,[1] mainly due to its enforcement on the Orthodox parishes, which stirred several massive uprisings, particularly the Khmelnytskyi Uprising, of the Zaporozhian Cossacks because of which the Commonwealth lost Left-bank Ukraine. By the end of the 18th century, through parallel persecutions of Orthodoxy, it would become the sole church for Ruthenians living in the Commonwealth. After the Partitions of Poland, which saw all but the Galician part of Ukraine enter into the Russian Empire, within decades all but the Chełm Eparchy would revert to Orthodoxy. The latter would be forcibly converted in 1875. In Austrian Galicia, however, the church underwent a transformation to one of the founding cornerstones of the Ukrainian national awakening in the 19th century, first as a centre for Western Ukrainian Russophilia and then for Ukrainophilia. It would remain a vital centre for Ukrainian culture during the Second Polish Republic and of Ukrainian nationalism during the Second World War. Although between 1946 and 1989 it was forcibly adjoined to the Russian Orthodox Church by Soviet authorities, it was resurrected as the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the prelude to Ukraine's independence.

The union was solemnly and publicly proclaimed in the Hall of Constantine in the Vatican. Canon Eustachy Wołłowicz, of Vilnius, read in Ruthenian and Latin the letter of the Ruthenian episcopate to the Pope, dated 12 June 1595. Cardinal Silvio Antoniani thanked the Ruthenian episcopate in the name of the Pope, and expressed his joy at the happy event. Then Adam Pociej, Bishop of Vladimir, in his own name and that of the Ruthenian episcopate, read in Latin the formula of abjuration of the Greek Schism, Bishop Cyril Terlecki of Lutsk read it in Ruthenian, and they affixed their signatures. Pope Clement VIII then addressed to them an allocution, expressing his joy and promising the Ruthenians his support. A medal was struck to commemorate the event, with the inscription: Ruthenis receptis. On the same day the bull Magnus Dominus et laudabilis nimis was published,[2] announcing to the Roman Catholic world the return of the Ruthenians to the unity of the Roman Church. The bull recites the events which led to the union, the arrival of Pociej and Terlecki at Rome, their abjuration, and the concession to the Ruthenians that they should retain their own rite, saving such customs as were opposed to the purity of Catholic doctrine and incompatible with the communion of the Roman Church. On 7 February 1596, Pope Clement VIII addressed to the Ruthenian episcopate the brief Benedictus sit Pastor ille bonus, enjoining the convocation of a synod in which the Ruthenian bishops were to recite the profession of the Catholic Faith. Various letters were also sent to the Polish king, princes, and magnates exhorting them to receive the Ruthenians under their protection. Another bull, Decet Romanum pontificem, dated 23 February 1596, defined the rights of the Ruthenian episcopate and their relations in subjection to the Holy See.[3]

It was agreed that the filioque should not be inserted in the Nicene Creed,[lower-alpha 1] although the Ruthenian clergy professed and taught the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son. The bishops asked to be dispensed from the obligation of introducing the Gregorian Calendar, so as to avoid popular discontent and dissensions, and insisted that the king should grant them, as of right, the dignity of senators.[3]

The union was strongly supported by the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Sigismund III Vasa, but opposed by some bishops and prominent nobles of Rus, and perhaps most importantly, by the nascent Cossack movement for Ukrainian self-rule. The result was "Rus fighting against Rus," and the splitting of the Church of Rus into Greek Catholic and Greek Orthodox jurisdictions.

See also

- Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

- Belarusian Greek Catholic Church

- Ruthenian Catholic Church

- Union of Uzhhorod

- History of Christianity in Ukraine

- Jeremi Wiśniowiecki

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic theological differences

- Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic ecclesiastical differences

Notes

- ↑ See the 1575 Profession of faith prescribed for the Greeks.[4](nn. 1303, 1307, 1863–1870, 1985–1987)

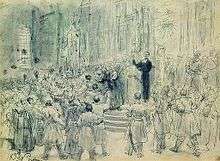

- ↑ In 1893, Russian painter Ilya Repin "depicted the moment when a Jesuit monk encourages residents of Vitebsk join the union," in a drawing on the theme of "preaching Kuntsevych".[5]

References

- ↑ Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European history and civilization (3rd. pbk. ed.). New Brunswick [u.a.]: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813507996.

- ↑ Pope Clement VIII (1753) [promulgated 1595-12-23]. "Unio Nationis Ruthenae cum Ecclesia Romana". In Cocquelines, Charles. Bullarum diplomatum et privilegiorum sanctorum Romanorum pontificum (in Latin). T.5 pt.2. Rome: Hieronymi Mainardi. pp. 87–92. OCLC 754549972.

- 1 2

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Palmieri, Aurelio (1912). "Union of Brest". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 15. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Palmieri, Aurelio (1912). "Union of Brest". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 15. New York: Robert Appleton. - ↑ Denzinger, Heinrich; Hünermann, Peter; et al., eds. (2012). Enchiridion symbolorum: a compendium of creeds, definitions and declarations of the Catholic Church (43rd ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 0898707463.

- ↑ Brodskiĭ, Iosif; Moskvinov, V. N., eds. (1969). Новое о Репине : статьи и письма художника. Воспоминания учеников и друзей. Публикации (in Russian). Leningrad: Художник РСФСР. p. 389. OCLC 4599550.

[...] 1893 года на тему 'Проповедь Кунцевича', посвященных одному из героических эпизодов в жизни белорусского народа. Художник изобразил момент, когда монах-иезуит призывает жителей Витебска примкнуть к унии, [...]

Further reading

- Magocsi, Paul R.; Pop, Ivan, eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of Rusyn history and culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3566-3.

- Pekar, Athanasius (1992). "The Union of Brest and attempts to destroy it". Analecta Ordinis S. Basilii Magni. Romae: Sumptibus PP. Basilianorum. 20: 152–170. Archived from the original on 2011-01-07.

- Senyk, Sophia (1996). "The background of the Union of Brest. part 1". Analecta Ordinis S. Basilii Magni. Romae: Sumptibus PP. Basilianorum. 21: 103–144. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. "The background of the Union of Brest. part 2". Archived from the original on 2011-01-07.

External links

- "Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church". Religious Information Service of Ukraine. Lviv: Institute of Religion and Society of the Ukrainian Catholic University. 2011-08-15. Archived from the original on 2013-03-20.

- The text

- FAMILY TREES of priests of the Byzantine-rite church in SLOVAKIA 1650-2006

- At the Service of Church Unity