Brown & Sharpe

Brown & Sharpe is a division of Hexagon AB, a Swedish multinational corporation focused mainly on metrological tools and technology. During the 19th and 20th centuries, Brown & Sharpe was one of the best-known and most influential machine tool builders and was a leading manufacturer of instruments for machinists (such as micrometers and indicators). Its reputation and influence were such that its name is often considered to be inseparably paired with certain industrial standards that it helped establish, including:

- The American wire gauge (AWG) standards for wire;

- The Brown & Sharpe taper in machine tool spindle tapers; and

- The Brown & Sharpe worm threadform for worm gears.

Since being acquired by Hexagon Metrology in 2001, Brown and Sharpe has concentrated exclusively on metrology equipment.[1]

History

Founding (1833) to World War I era (1916)

Brown & Sharpe was founded in Providence, Rhode Island by David Brown and his son Joseph R. Brown. The elder Brown retired in 1841 the younger Brown formed a partnership with Lucian Sharpe in 1853. The company was incorporated in 1868. In 1866 Samuel Darling joined the partnership and the firm changed its name to Darling, Brown and Sharpe until Darling's interest was bought out in 1892.

Brown & Sharpe was instrumental in the development of machine tools and machining technology (including toolmaking, metrology, production, etc.). It was responsible for the improvement and wider dissemination of milling machines, micrometers, turret lathes, screw machines, and other tools. A thorough account of the details is given in a seminal classic of machine tool history, Joseph W. Roe's English and American Tool Builders (1916).[3]

World War I through World War II

Like most machine tool builders, Brown & Sharpe rode a business cycle rollercoaster during these decades. After being kept very busy during World War I, builders suffered a slump in the post–World War I recession and depression of 1920–21. The Roaring Twenties brought renewed sales, but then the Great Depression slashed them. The armament-buildup period of 1936 to 1940 again renewed machine tool activity, and then the World War II materiel effort exploded demand, pushing it to record heights.

Brown and Sharpe machine tools were a mainstay of American metal manufacturing until the late 20th Century and could be found in most machine shops and factories which worked with metal. Additionally, Brown and Sharpe made calipers and micrometers which were essential to products built to fine tolerances.

Post-World War II era

Shortly after World War II, Henry D. Sharpe, Jr. succeeded his father as president of Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company, at which point it evolved into a new and modern company built, or at least designed, to last. The firm stopped producing its old stalwarts: sewing machines, hair clippers, and certain categories of machine tools (including its line of milling machines). Instead the company refocused on the mass production of automatic screw machines as it completed a three-year, $4 million refitting program for its Providence plant in 1957. In keeping with the latest management theories, Sharpe also reorganized the company into separate divisions, with each one responsible for its own profit and loss. During this era, Brown & Sharpe began to experiment with international expansion and the company established its first overseas subsidiary in Plymouth, England, in 1955. Between 1957 and 1961 the company further expanded through the acquisition of related manufacturers, most notably the machine-producing Double A Products Company.

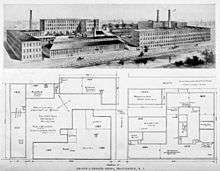

In the aftermath of the changes that swept the company, it came to outgrow its central plant just west of downtown Providence. In 1964, Brown & Sharpe followed other Providence-based manufacturers out of the city, moving instead to suburban North Kingstown, Rhode Island. These relocations were made possible by the explosion of automobile ownership in the postwar era, which contributed to the rapid growth of Providence's suburbs throughout the 1950s. Given that the company's workers had become more mobile and that the majority of them now lived in these suburban areas, Brown & Sharpe saw an easy opportunity to relocate into a more practical facility. The new plant, dubbed Precision Park as a nod to Brown & Sharpe's history of pioneering manufacture of precise measurement tools, contained 700,000 square feet (65,000 m2) of easily adaptable floor space. Unlike the old Providence facility, Precision Park had just one story, which allowed for the efficient horizontal movement of materials and improved upon the clumsy vertical circulation system employed in its old plant.

While the company never again reached its wartime peak employment of 11,000, it still employed a substantial 3,394 workers in 1976. These employment levels were partly the result of a concerted effort to smooth production across the recessions of the 1970s and keep employment steady. During this time, President Sharpe and his successor Don Roach sympathized with the workers, whose concerns over job security were only natural considering the cyclical nature of machine-tool manufacturing and the downward trends in manufacturing locally.

Yet despite the policies aimed at maintaining job security, Brown & Sharpe began to make demands that sat uneasily with its workers and union leaders. In 1981, President Don Roach insisted that the company exercise the ability to shift machinists between jobs as needed, but many workers worried that this policy would ignore traditional seniority privileges. In response, 1,600 union workers, members of the International Association of Machinists District Lodge 64, walked out on their jobs in what would become the longest-lasting strike in the nation's history and one of the most antagonistic in recent memory. The strike's hostility transcended the mere debate over the company's labor policy and brought up questions of whether Brown & Sharpe needed its Rhode Island work force at all. The hostilities between labor and management, as well as the deteriorating status of organized labor at the national level, are symbolized well by the incident of March 22, 1982, in which 800 picketers clashed with the state and local police force, leading to the use of tear gas on the former employees. Governor J. Joseph Garrahy publicly apologized for the actions of the police, which appeared unduly severe to many Rhode Island citizens. Although the strike legally continued after the tear-gas incident, the picket line largely disbanded and many workers realized it was time to move on. It was not until 1998, nearly seventeen years after the strike began, that the Rhode Island Supreme Court ended the legal battle, ultimately siding with Brown & Sharpe in its plea that it had not illegally forced the strike. By this point, both Brown & Sharpe and its erstwhile work force were retreating from manufacturing in Rhode Island.

During the long legal proceedings Brown & Sharpe continued to transform as a manufacturer and as an employer. During the 1980s and 1990s Brown & Sharpe started focusing more and more on developing coordinate-measuring machines (CMMs), devices for dimensional measuring, as a more modern and larger progression to their established micrometers. The company began to lose money as it shifted production away from machine tools and toward advanced metrology equipment, losing $14.6 million in 1990. By 1993, employment in North Kingstown had fallen to 700, compared with 2,000 in 1982 and over 3,500 in 1976. In 1994 Brown & Sharpe acquired DEA of Italy an established manufacturer of CMMs. In 2001, substantially all of the assets of the Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company, including the intellectual property, designs, trademarks, facilities and inventory, were acquired by Hexagon AB, without the acquisition of the Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company itself. The Brown & Sharpe brand of measurement products lives on under the stewardship of the Hexagon Metrology division of Hexagon AB, which retained many of the key individuals from the former Brown & Sharpe company. Brown & Sharpe brand hand tools are now manufactured by Hexagon Metrology's TESA division in Switzerland.[1]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brown & Sharpe. |

References

- 1 2 "Hexagon Metrology History". HexagonMetrology.com. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- ↑ Arnold, Horace L. "Modern Machine-Shop Economics. Part II" in Engineering Magazine 11. 1896

- ↑ Roe 1916, pp. 202–215.

Bibliography

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

Further reading

- Rolt, L.T.C. (1965), A Short History of Machine Tools, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press, OCLC 250074. Co-edition published as Rolt, L.T.C. (1965), Tools for the Job: a Short History of Machine Tools, London: B. T. Batsford, LCCN 65080822. (edit)