Byzantine enamel

The craft of cloisonné enameling is a metal and glass-working tradition practiced in the Byzantine Empire from the 6th to the 12th century. The Byzantines perfected an intricate form of vitreous enameling, allowing the illustration of small, detailed, iconographic portraits.

Overview

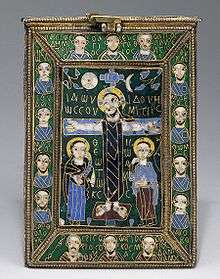

The development of the Byzantine enamel art occurred between the 6th and 12th centuries.[1] The Byzantines perfected a form of enameling called cloisonné, where gold strips are soldered to a metal base plate making the outline of an image. The recessed spaces between the gold filigreed wire are then filled with a colored glass paste, or flux, that fills up the negative space in the design with whatever color chosen. Byzantine enamels usually depict a person of interest, often a member of the imperial family or a Christian icon. Enamels, because they are created from expensive materials such as gold, are often very small. Occasionally they are made into medallions that act as decorative jewelry or are set in ecclesiastical designs such as book covers, liturgical equipment like the chalice and paten, or in some examples, royal crowns. Collections of small enamels may be set together to make a larger, narrative display, such as in the Pala d'Oro altarpiece.[2] Many of the examples of Byzantine enamel known today have been repurposed into a new setting, making dating particularly difficult where no inscriptions or identifiable persons are visible. The Latin Crusaders, who sacked Constantinople in 1204, took many examples of Byzantine enamel with them back West. The destruction of Constantinople meant that the production of enamel artwork went into downfall in the 13th century. It is possible that many examples left in the city were melted down and repurposed by the Ottoman Empire, who cared little about the religious significance of the art and could reuse the gold but not the glass.[3]

Origins

The art of vitreous enameling is an ancient practice with origins that are hard to pinpoint.[4] There are a few places that Byzantine craftsmen could have picked up the technique. Enameling is thought to have existed in an early form in ancient Egypt, where examples of gold ornaments containing glass paste separated by strips of gold have been found in tombs.[5] However, there are questions about whether the Egyptians were using actual enameling techniques; it is possible that instead they were casting glass stones which were then enclosed, set into metal frames, and then sanded to a finish, similarly to how precious stones are set.[6] In first century BCE Nubia, a method appears of soldering gold strips to a metal base, most often gold, and then filling in the sectioned off recesses with glass flux. This method, called cloisonné, later became the preferred style of enameling in the Byzantine Empire.[7]

The enamel workshops within the Byzantine Empire likely perfected their techniques through their connections with Classical Greek examples.[8] The Greeks were already experts in enameling, soldering a filagree onto a flat base and later adding a paste of glass, or a liquid flux, to the base piece.[9] The entire work was then fired, melting the glass paste into the frame to create the finished work. Occasionally, the ancient Greek craftsman would apply the glass flux to the base with the aid of a brush.[10] The Romans, who were experienced in glass production already, would carve a recess into the base plate and then pour glass flux into each enclosure.[11] The metal peeking through between the recessed glass would create the outline of the image. This technique is called champlevé, and is considerably easier than the cloisonné form of enameling practiced by the Greeks and Byzantines.

Byzantine enamel tradition

The Byzantines were the first craftsmen to begin illustrating detailed miniature scenes in enamel. A few examples of early Byzantine enamel frames missing the glass flux have been found, and it has been hypothesized that they were used as educational tools in workshops. Some incomplete enamel base plates show indentations marking the line to which the gold wire would be attached, indicating how designs were outlined before soldering and enameling began. Because they were not carving recesses into a base plate and then filling the hole with glass flux, Byzantine workers could also use gold wire to create patterns that would not separate recesses from one another, resulting in a style that appears more like a drawn line.

Most of the Byzantine enamels known today are from the 9th to 12th centuries. The period of Iconoclasm from 726-787 CE meant that most examples predating the 8th century were destroyed because of their iconographic nature, though there are a few examples thought to have been made earlier.[12] One of the earliest examples of Byzantine enamel work is a medallion created in either the late 5th or early 6th century and features a bust portrait of Empress Eudoxia.[13] The period after Iconoclasm saw an upswing in the production of iconic portraits, to which the intricate form of cloisonné developed by the Byzantines lends itself easily. Most enamel works known today have been housed in western Europe since the beginning of the 13th century. Any examples of enamel work still inside Constantinople immediately prior to its destruction were lost or destroyed.[14]

Enamels are considered a "Minor Art" because of their small size, which likely led to their increase in use as decoration for small, portable containers holding holy relics. In this tradition, many enameled pieces found their way to the western empire by way of pilgrimage and gifts from the imperial family in Constantinople.[15] The high value and relatively small size of enamel pieces meant that they were made for an aristocratic audience, most likely commissioned by the imperial family, often as gifts for other royals or for the churches they patronized. For example, there is evidence that Emperor Justinian II (565-578) sent enamels to Queen Radegund of France.[16] Another possible transmission for Byzantine enamels to the west came in the form of imperial marriages. In 927, the German Emperor Otto II married the niece of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces, princess Theophanu, and she supposedly introduced imperial goldsmiths and enamelers to the German church.[17] Many famous examples of Byzantine enamel are staurothekes, relics containing fragments of the True Cross, which were greatly prized in both the east and the west, therefore more survive still in modern collections. It is likely that a staurotheke was one of the first gifts sent from the East to the West. There is some evidence that the Crusaders carried the reliquaries in front of their military campaigns as Byzantine emperors were known to have presented them.[18]

Notable examples

Fieschi-Morgan Staurotheke

The Fieschi-Morgan Staurotheke is an example of Byzantine enameling dating to the early 9th century, though some suggest as early of a creation date as 700. It was quite possibly made in Constantinople, though there are debates around its origins, some suggesting it was made in Syria based on the inconsistencies in the Greek lettering.[19] It is currently housed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Supposedly, the Fiesch-Morgan Staurotheke belonged to Pope Innocent IV and was brought to the west by the Fieschi family during the Crusades.[20] The lid of the box features Christ on the crucifix, a style not usually seen in Byzantine art until the end of the 6th century, remaining uncommon throughout the period. The work is not particularly refined, signaling the creator was perhaps not familiar with cloisonné work.[21]

Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary, also known as St. Stephen's Crown, has been used as the coronation crown of Hungary since the year 1000, when the Hungarian royals introduced Christianity to the country.[22] It contains mostly Byzantine enamelwork originating from Constantinople, though it isn't proven they were crafted originally for this purpose.[23] The enamels are mounted around the base, with several plaques attached at the top. One enamel shows Christ, seated on the imperial throne and giving blessing. Another enamel, positioned at the back of the crown, illustrates a bust portrait of Emperor Michael VII Ducas (1071-1078), next to another plaque of his son Constantine. The Hungarian King Géza I (1074-1077) is also featured, though he is not wearing a nimbus like Michael VII Ducas or Constantine, which indicates his status as lower than that of the Byzantine Emperors.[24]

Beresford Hope Cross

The Beresford Hope Cross is a pectoral cross intended for use as a reliquary.[25] One one side Christ is depicted at the Crucifixion, while the other shows Mary praying between busts of John the Baptist, Perter, Andrew, and Paul. The dating is contentious, but most agree it was made in the 9th century.[26] The style is similar to the Fieschi-Morgan Staurotheke; the cloisonné of both is unrefined and stylistically sloppy compared to other examples. The inconsistencies in the Greek lettering on the cross mean that it is possible the piece was not made in the Byzantine Empire, but in southern Italy, where the Lombards had active metal workshops of their own.[27]

Problems with dating and origins

Many examples of Byzantine enamel are hard to date because of a lack of inscription or identifiable individual. In these cases, guesses must be made to the date of the object in question through a comparison with similar objects with known dates. This can be done by examining material sources and by comparing styles. For example, objects with green glass composed of similar material might be grouped within a similar date range. Origins of Byzantine enamel work are often even harder to pinpoint, as nearly everything made has been housed in the West since the early 13th century. One way of guessing the origins of a piece is by examining the quality of the Greek lettering; the more accurate the Greek, the more likely the work came directly from the Byzantine Empire.

Byzantine influence on Germanic metalwork

The Migration Period of early medieval art sees a concurrent form of metalwork influenced by the Goths' migration through the eastern Roman Empire into the west, accumulating techniques and materials from Byzantine and Mediterranean sources.[28] However, instead of using traditional Byzantine enamel techniques, they often employed a chip-carving technique, where stones such as garnets are cut to fit into a wire frame. This has the appearance of cloisonné, but is more similar to the Ptolemaic Egyptian style. The appearance of cloisonné jewelry from Germanic workshops in the mid-5th century is a complete break with the culture’s traditions, signaling that they likely picked up the technique from the east, where the Byzantine Empire was gaining a foothold as the center of the Late Roman Empire.[29] It has been proposed that Late-Roman workshops in Constantinople produced semi-manufactured enamel parts intended for assembly in the west.[30]

References

- ↑ "Enamelwork". Britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Campbell, Marian (1983). An Introduction to Medieval Enamels. Owings Mills, Maryland: Stemmer House Publishers, Inc. p. 11.

- ↑ Wessel, Klaus (1967). Byzantine Enamels. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society Ltd. p. 11.

- ↑ Wessel p.11

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Campbell, p.10

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Wessel, p. 11

- ↑ Campbell, p.10

- ↑ Campbell, p.10

- ↑ Wessel, p. 10

- ↑ Wessel, p. 8

- ↑ Wessel, p. 8

- ↑ Campbell, p. 17

- ↑ Wessel, p. 10

- ↑ Wessel p.43

- ↑ Wessel p.42

- ↑ Wessel p.44

- ↑ "Return of the Holy Crown of St. Stephen".

- ↑ Wessel, p.111

- ↑ Wessel, p.112

- ↑ Wessel, p.50

- ↑ Wessel, p.51

- ↑ Wessel, p.51

- ↑ Nees, Lawrence (2002). Early Medieval Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Deppert-Lippitz, Barbara (2000). Late Roman and Early Byzantine Jewelry in the Mid 5th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 73.

- ↑ Arrhenius, Birgit (2000). Garnet Jewelry of the Fifth and Sixth Centuries. Yale University Press. p. 214.