Ceratonia siliqua

| Carob tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of Ceratonia siliqua | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Ceratonia |

| Species: | C. siliqua |

| Binomial name | |

| Ceratonia siliqua L. | |

Ceratonia siliqua, commonly known as the carob tree (from Arabic خَرُّوبٌ kharrūb and Hebrew חרוב harubh), St John's-bread,[1] or locust bean[2] (not to be confused with the African locust bean) is a species of flowering evergreen shrub or tree in the pea family, Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated for its edible pods, and as an ornamental tree in gardens. The ripe, dried pod is often ground to carob powder, which is used to replace cocoa powder. Carob bars, an alternative to chocolate bars, are often available in health-food stores.

The carob tree is native to the Mediterranean region, including Southern Europe, Northern Africa, the larger Mediterranean islands, the Levant and Middle-East of Western Asia into Iran; and the Canary Islands and Macaronesia.[3][4] The carat, a unit of mass for gemstones, and of purity for gold, takes its name, indirectly, from the Greek word for a carob seed, kerátion.

Carob tree

Morphology

The Ceratonia siliqua tree grows up to 15 m (49 ft) tall. The crown is broad and semispherical, supported by a thick trunk with brown rough bark and sturdy branches. Leaves are 10 to 20 cm (3.9 to 7.9 in) long, alternate, pinnate, and may or may not have a terminal leaflet. It is frost-tolerant to roughly 20 °F.

Most carob trees are dioecious, some are hermaphrodite. The male trees do not produce fruit.[5] The trees blossom in autumn. The flowers are small and numerous, spirally arranged along the inflorescence axis in catkin-like racemes borne on spurs from old wood and even on the trunk (cauliflory); they are pollinated by both wind and insects.

The fruit is a legume (also known less accurately as a pod), that can be elongated, compressed, straight, or curved, and thickened at the sutures. The pods take a full year to develop and ripen. The sweet ripe pods eventually fall to the ground and are eaten by various mammals , thereby dispersing the hard seed. The seeds contain leucodelphinidin, a colourless chemical compound.[6]

Habitat

Although used extensively for agriculture, carob can still be found growing wild in eastern Mediterranean regions, and has become naturalized in the west.[7]

The tree is typical in the southern Portuguese region of the Algarve, where it has the name alfarrobeira (for the tree), and alfarroba (for the fruit), as well as in southern Spain (Spanish: algarrobo, algarroba), Catalonia and Valencia (Catalan: garrofer, garrofa), Malta (Maltese: ħarruba), on the Italian islands of Sicily and Sardinia (Italian: carrubo, carruba), Croatian islands near Split (Croatian: rogač), and in Southern Greece, Cyprus, as well as on many Greek islands such as Crete and Samos. The common Greek name is (Greek: χαρουπιά, charoupia), or (Greek: ξυλοκερατιά, ksilokeratia), meaning "wooden horn".

In Turkey, it is known as keçiboynuzu, meaning "goat's horn".[7][8] The various trees known as algarrobo in Latin America (Albizia saman in Cuba and four species of Prosopis in Argentina and Paraguay) belong to a different subfamily, Mimosoideae.

Ecology

The carob genus, Ceratonia, belongs to the Fabaceae (legume) family, and is believed to be an archaic remnant of a part of this family now generally considered extinct. It grows well in warm temperate and subtropical areas, and tolerates hot and humid coastal areas. As a xerophyte (drought-resistant) species, carob is well adapted to the ecological conditions of the Mediterranean region with 250 to 500 mm of rainfall per year.[7]

Carob trees can survive long drought periods, but to grow fruit, they need 500 to 550 mm rainfall per year.[7] Trees prefer well-drained, sandy loams and are intolerant of waterlogging, but the deep root systems can adapt to a wide variety of soil conditions and are fairly salt-tolerant (up to 3% NaCl in soil).[7] After irrigation with saline water in summer, carob trees could possibly also recover during rainfalls in winter.[9] In some experiments young carob trees could uphold basical physiological functions at 40 mmol NaCl/l.[9]

Not all legume species can develop a symbiosis with rhizobia to use atmospheric nitrogen. For carob, it remains unclear if it has this ability: Some findings suggest that it is not able to form nodules with rhizobia,[7] while in another study trees have been identified more recently with nodules containing bacteria believed to be from the Rhizobium genus.[10] However, measuring the 15N-signal in plant tissue did not support that carob trees in the field can use atmospheric nitrogen.[11]

Uses

Food

.jpg)

Carob consumed by humans is the dried (and sometimes roasted) pod. The pod consists of two main parts: the pulp accounts for 90% and the seeds for 10% of the pod weight.[7][12]

Carob is mildly sweet and is used in powdered, chip, or syrup form as an ingredient in cakes and cookies, and as a substitute for chocolate. Carob bars are widely available in health food stores. A traditional sweet, eaten during Lent and Good Friday, is also made from carob pods in Malta. Dried carob fruit is traditionally eaten on the Jewish holiday of Tu Bishvat.

While chocolate contains levels of theobromine which are toxic to some mammals, carob contains absolutely no caffeine and no theobromine, so is used to make chocolate-flavored treats for dogs. [13][14]

Carob pod meal is used as an energy-rich feed for livestock, particularly for ruminants, though its high tannin content may limit its use.[15] Carob pods were mainly used as animal fodder in the Maltese Islands, apart from times of famine or war when they formed part of the diet of many Maltese. In the Iberian Peninsula, carob pods were used to feed donkeys.

The pulp is about 48–56% sugars and 18% cellulose and hemicellulose.[7] Some differences in sugar content are seen between wild and cultivated types: sucrose = about 531 g/kg dry weight in cultivated varieties and about 437 g/kg in wild varieties. Fructose and glucose levels do not differ between cultivated and wild carob.[16] Carob pulp is sold as flour or chunks.[12]

The production of locust bean gum (LBG), used in the food industry, is the economically most important use of carob seeds (and nowadays of the carob as a whole). It is produced from the endosperm, which accounts for 42–46% of the seed and is rich in galactomannans (88% of endosperm dry mass). For 1 kg LBG, 3 kg of kernels are needed which come from around 30 kg carob tree fruit. Galactomannans are hydrophilic and swell in water. LBG is used as a thickening agent, stabilizer, gelling agent, or as a substitute for gluten in low-calorie products. If galactomannans are mixed with other gelling substances such as carrageenan, they can be used to thicken food. This is used extensively in canned food for animals to get the jellied texture.[12]

The embryo (20-25% of the seed's weight) is rich in proteins (50%) and its flour can be used in human and animal nutrition.[7] The testa (30–33% of the seed's weight) is the seed coat and consists of cellulose, lignin, and tannin.[12]

Syrup, drinks

In Cyprus, carob syrup is known as Cyprus's black gold, and is widely exported. In Malta, a syrup (ġulepp tal-ħarrub) is made out of carob pods. This is a traditional medicine for coughs and sore throat. Carob syrup is also used in Crete as a natural sweetener, and is considered a natural source of calcium. It contains three times more calcium than milk. It is also rich in iron, phosphorus, and natural fibers (Due to its strong taste, it can be found mixed with orange or chocolate).[17]

Carob juice drinks are traditionally drunk during the Islamic month of Ramadan. Crushed pods may be used to make a beverage; compote, liqueur, and syrup are made from carob in Turkey, Malta, Portugal, Spain, and Sicily. Several studies suggest that carob may aid in treating diarrhea in infants.[18] In Libya, carob syrup (there called rub) is used as a complement to asida. The so-called carob syrup made in Peru is actually from the fruit of the Prosopis nigra tree.

Ornamental

C. siliqua is widely cultivated in the horticultural nursery industry as an ornamental plant for planting in Mediterranean climate and other temperate regions around the world, as its popularity in California and Hawaii shows. The plant develops a sculpted trunk and ornamental tree form when 'limbed up' as it matures, otherwise it is used as a dense and large screening hedge. If one does not care about the size of the legume harvests, the plant is very drought tolerant, and it is used in xeriscape landscape design for gardens, parks, and public municipal and commercial landscapes.[3]

Cultivation

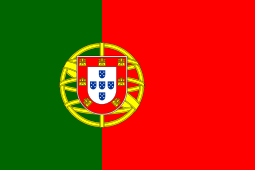

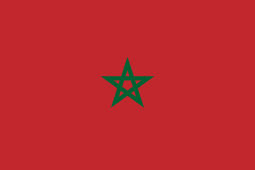

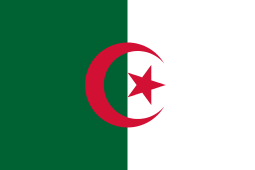

According to FAO, the top carob-producing countries are (in metric tonnes, 2012): Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[19]

Spain 40,000 (F)

Spain 40,000 (F) Italy 30,841

Italy 30,841 Portugal 23,000 (F)

Portugal 23,000 (F) Greece 22,000 (F)

Greece 22,000 (F) Morocco 20,500 (F)

Morocco 20,500 (F) Turkey 14,218

Turkey 14,218 Cyprus 5,186

Cyprus 5,186 Algeria 3,136

Algeria 3,136 Lebanon 2,300 (F)

Lebanon 2,300 (F)

(F) = FAO estimate

Cultivation and orchard management

The vegetative propagation of carob is restricted due to its low adventitious rooting potential, which could be improved by using better grafting techniques, such as air layering.[20] Therefore, seeds are still widely used as the propagation medium. The sowing occurs in pot nurseries in early spring and the cooling- and drying-sensitive seedlings are then transplanted to the field in the next year after the last frost. Carob trees enter slowly into production phase. Where in areas with good growing conditions, the cropping starts 3–4 years after budding, the nonbearing period can take up to 8 years in regions with marginal soils. Full bearing of the trees occurs mostly at a tree-age of 20–25 years where the yield stabilizes.[7] The orchards are traditionally planted in low densities around 25–45 trees/hectare. Hermaphrodite plants or male trees, which produce no or fewer pods, respectively, are usually planted in lower densities in the orchards as pollenizers.

Intercropping with other tree species is widely spread. Not much cultivation management is required. Only light pruning and occasional tilling to reduce weeds is necessary. Nitrogen-fertilizing of the plants has been shown to have positive impacts on yield performance.[7] Although it is native to moderately dry climates, two or three summers irrigation greatly aid the development, hasten the fruiting, and increase the yield of a carob tree.[21]

Harvest and postharvest treatment

The most labour-intensive part of carob cultivation is harvesting, which is often done by knocking the fruit down with a long stick and gathering them together with the help of laid-out nets. This is a delicate task because the trees are flowering at the same time and care has to be taken not to damage the flowers and the next year's crop. The literature recommends research to get the fruit to ripen more uniformely or also for cultivars which can be mechanically harvested (by shaking).[7]

After harvest, carob pods have a moisture content of 10–20% and should be dried down to a moisture content of 8% so the pods do not rot. Further processing separates the kernels (seeds) from the pulp. This process is called kibbling and results in seeds and pieces of carob pods (kibbles). Processing of the pulp includes grinding for animal feed production or roasting and milling for human food industry. The seeds have to be peeled which happens with acid or through roasting. Then the endosperm and the embryo are separated for the different uses.[7]

Pests and diseases

Only a few pests are known to cause severe damage in carob orchards, so they have traditionally not been treated with pesticides. Some generalist pests such as the larvae of the leopard moth (Zeuzera pyrina L.), small rodents such as rats (Rattus spp.) and gophers (Pitymys spp.) can cause damage occasionally in some regions. Only some cultivars are severely susceptible to mildew disease (Oidium ceratoniae C.). One pest directly associated with carob is the larva of the carob moth (Myelois ceratoniae Z.), which can cause extensive postharvest damage.[7]

Cultivars and breeding aims

Most of the roughly 50 known cultivars[7] are of unknown origin and only regionally distributed. The cultivars show high genetic and therefore morphological and agronomical variation.[7] No conventional breeding by controlled crossing has been reported, but selection from orchards or wild populations has been done. Domesticated carobs (C. s. var. edulis) can be distinguished from their wild relatives (C. s. var. silvestris) by some fruit-yielding traits such as building of greater beans, more pulp, and higher sugar contents. Also, genetic adoption of some varieties to the climatic requirements of their growing regions has occurred.[7] Though a partially successful breaking of the dioecy happened, the yield of hermaphroditic trees still cannot compete with that of female plants, as their pod-bearing properties are worse.[22] Future breeding would be focused on processing-quality aspects, as well as on properties for better mechanization of harvest or better-yielding hermaphroditic plants. The use of modern breeding techniques is restricted due to low polymorphism for molecular markers.[7]

Etymology and history

The word carob comes from Middle French carobe (modern French caroube), which borrowed it from Arabic خَرُّوبٌ (kharrūb, "locust bean pod"),[23] ultimately perhaps from Akkadian language kharubu or Aramaic kharubha, related to Hebrew harubh.[24] Ceratonia siliqua, the scientific name of the carob tree, derives from the Greek kerátiοn κεράτιον 'fruit of the carob (from keras κέρας 'horn'), and Latin siliqua 'pod, carob'.

The unit "carat", used for weighing precious metal and stones, also comes from κεράτιον, as

alluding to an ancient practice of weighing gold and gemstones against the seeds of the carob tree by people in the Middle East. The system was eventually standardized, and one carat was fixed at 0.2 grams.

| ||

| Carob-Pod n(dj)m (nedjem) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Carob was eaten in Ancient Egypt. It was also a common sweetener and was used in the hieroglyph for "sweet" (nedjem).

In late Roman times, the pure gold coin known as the solidus weighed 24 carat seeds (about 4.5 grams). As a result, the carat also became a measure of purity for gold. Thus 24-carat gold means 100% pure, 12-carat gold means the alloy contains 50% gold, etc.[25]

Subsistence on carob pods is mentioned in the Talmud: Berakhot reports that Rabbi Haninah subsisted on carob pods.[26] It is probably also mentioned in the New Testament, in which Matthew 3:4 reports that John the Baptist subsisted on "locusts and wild honey"; the Greek word ἀκρίδες translated "locusts" may refer to carob pods, rather than to grasshoppers.[26] Again, in Luke 15:16, in the Parable of the Prodigal Son, when the Prodigal Son is in the field in spiritual and social poverty, he desires to eat the pods that he is feeding to the swine because he is suffering from starvation. The use of the carob during a famine is likely a result of the carob tree's resilience to the harsh climate and drought. During a famine, the swine were given carob pods so that they would not be a burden on the farmer's limited resources.

Use of the carob plant dates back to Mesopotamian culture (modern day Iraq). The carob pods were used to create juices, sweets, and were highly prized due to their many uses. The carob tree is mentioned frequently in texts dating back thousands of years, outlining its growth and cultivation in the Middle East and North Africa. The carob tree is mentioned with reverence in "The Epic of Gilgamesh", one of the earliest works of literature in existence.

The Jewish Talmud features a parable of altruism, commonly known as "Honi and the Carob Tree", which mentions that a carob tree takes 70 years to bear fruit; meaning that the planter will not benefit from his work, but works in the interest of future generations.[27] In reality, the fruiting age of carob trees varies (see under cultivation).

During the Second World War, the people of Malta commonly ate dried carob pods and prickly pears as a supplement to rationed food.

Gallery

Natural-low branching form of tree in native habitat at WWF Oasis of Monte Arcosu, Sardinia, Italy

Natural-low branching form of tree in native habitat at WWF Oasis of Monte Arcosu, Sardinia, Italy C. siliqua, close-up of leaves

C. siliqua, close-up of leaves- C. siliqua, abaxial and adaxial surfaces of leaflet

C. siliqua, close-up of female flower

C. siliqua, close-up of female flower C. siliqua, male flowers, which emanate a strong cadaverine odor (Cyprus, October 2013)

C. siliqua, male flowers, which emanate a strong cadaverine odor (Cyprus, October 2013) C. siliqua, green fruit pods, 15 cm (5.9 in) long, on tree

C. siliqua, green fruit pods, 15 cm (5.9 in) long, on tree- C. siliqua, green and ripe pods

Fruit of the carob tree

Fruit of the carob tree C. siliqua, seeds and dry pods

C. siliqua, seeds and dry pods- Carobs at the market

C. siliqua at the Shivta archaeological site, southern Israel

C. siliqua at the Shivta archaeological site, southern Israel

See also

- Ratti (a seed from which the Indian measure unit "tola" derived)

References

- ↑ ITIS Report Page: Ceratonia siliqua . accessed 5.11.2011

- ↑ REHM, S. ; ESPIG, G. "The cultivated plants of the tropics and subtropics : cultivation, economic value, utilization". - Weikersheim (DE) : Margraf, 1991. - viii,552 p. - p.220

- 1 2 NPGS/GRIN - Ceratonia siliqua information, accessed 5.11.2011

- ↑ "Tropicos - Name - !Ceratonia siliqua L.". tropicos.org.

- ↑ Sweet Crop Broadcast: 14/04/2013 1:11:16 PM Reporter: Prue Adams

- ↑ liberherbarum.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Battle I, Tous J (1997). Carob tree (PDF). Rome, Italy: International Plant Genetic Resources Institute. ISBN 978-92-9043-328-6. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ↑ "Turkish Cuisine". Turkish Cuisine. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- 1 2 Correia, P.J.; Gamaa, F.; Pestana, M.; Martins-Loução, M.A. (2010). "Tolerance of young (Ceratonia siliqua L.) carob rootstock to NaCl". Agricultural Water Management. 97: 910–916. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2010.01.022.

- ↑ M. Missbah El Idrissi; N. Aujjar; A. Belabed; Y. Dessaux; A. Filali-Maltouf (1996). "Characterization of rhizobia isolated from Carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua)". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 80 (2): 165–73. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03205.x.

- ↑ La Malfa, S.; Tribulato, E.; Gentile, A.; Gioacchini, P.; Ventura, M.; Tagliavini, M. (2010). "15N natural abundance technique does not reveal the presence of nitrogen from biological fixation in field grown carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) trees". Acta Horticulturae. 868: 191–195.

- 1 2 3 4 Rainer Droste (1993). Möglichkeiten und Grenzen des Anbaus von Johannisbrot (Ceratonia siliqua L.) als Bestandteil eines traditionellen Anbausystems in Algarve, Portugal. Institut für Pflanzenbau und Tierhygiene in den Tropen und Subtropen, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen.

- ↑ Craig, Winston J.; Nguyen, Thuy T. (1984). "Caffeine and theobromine levels in cocoa and carob products". Journal of Food Science. 49 (1): 302–303, 305. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb13737.x. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

No theobromine or caffeine has been detected in carob (Antonetti, 1978). Eighteen carob containing products were also analyzed for theobromine and caffeine content to determine whether any chocolate had been added to the carob products.... This addition of chocolate to some of the carob products could be an attempt to improve the organoleptic properties of the carob products. Table 2–Theobromine and caffeine content of carob products: Carob powder: Average theobromine content = none detected. Average caffeine content = none detected.

- ↑ Barbara Burg, Good Treats For Dogs Cookbook for Dogs: 50 Home-Cooked Treats for Special Occasions. Quarry Books, 2007, p. 28; C. J. Puotinen, The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care, McGraw Hill Professional, 2000, p. 81.

- ↑ Heuzé, V.; Sauvant, D.; Tran, G.; Lebas, F.; Lessire, M. (October 3, 2013). "Carob (Ceratonia siliqua)". Feedipedia.org. A programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Sugar profiles of the pods of cultivated and wild types of carob bean (Ceratonia siliqua L.) in Turkey". Food Chemistry. 100: 1453–1455. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.037.

- ↑ Maria T. (19 June 2015). "Bioaroma carob Syrup - ideal for sugar replacement-osteoporosis-weight loss". CretanSoil - best natural products.

- ↑ Fortier D, Lebel G, Frechette A (June 1953). "Carob flour in the treatment of diarrhoeal conditions in infants". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 68 (6): 557–61. PMC 1822828

. PMID 13059705.

. PMID 13059705. - ↑ "Major Food And Agricultural Commodities And Producers – Countries By Commodity". Fao.org. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Gubbuk, Hamide; Gunes, Esma; Ayala-Silva, Tomas; Ercisli, Sezai (2011). "Rapid Vegetative Propagation Method for Carob". Not Bot Hort Agrobot Cluj. 39 (1): 251–254.

- ↑ Bailey, Liberty Hyde (1914). The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ Zohary, Daniel (2013). "Domestication of the carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.)". Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 50:sup1: 141–145.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary , 1st ed. (1888), s.v. 'carob'

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "carob". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "carat". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- 1 2 "A Brief on Bokser". The Forward. 4 February 2005.

- ↑ Ravina; Ashi, Rav (eds.). Babylonian Talmud (in Aramaic-Talmudical). Ta'anis. pp. 23b.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Ceratonia siliqua |

- Crops and recipes

- Carob recipes, Cooks.com.

- "Recipe for the Egyptian Carob Drink", Egyptian-cuisine-recipes.com.

- "Interview of Australian carob producers", ABC.

- Turnbull LA, Santamaria L, Martorell T, Rallo J, Hector A (September 2006). "Seed size variability: from carob to carats". Biology Letters. 2 (3): 397–400. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0476. PMC 1686184

. PMID 17148413. Lay summary – New Scientist (May 9, 2006).

. PMID 17148413. Lay summary – New Scientist (May 9, 2006).

- Tree and images

- Purdue Univ: Fruits of Warm Climates: Carob treatment - horticulture and cultivars, species and native habitat treatment,

- PFAF Plant Database: Ceratonia siliqua — Carob

- U.C.CalPhotos: Carob —Ceratonia siliqua — Photo Gallery

- Encyclopedia.com: entry for Carob

- ""Caroubier" ("The Carob Tree" - book)" (PDF). (1.32 MB) (English)

- Leaves of carob tree, source of chocolate substitute, fight food-poisoning bacteria