Paraguay

Coordinates: 23°S 58°W / 23°S 58°W

| Republic of Paraguay |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Paz y justicia" (Spanish) "Peace and justice" |

||||||

| Anthem: Paraguayos, República o Muerte (Spanish) Paraguayans, Republic or Death |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Asunción 25°16′S 57°40′W / 25.267°S 57.667°W | |||||

| Official languages | ||||||

| Ethnic groups (2000) | ||||||

| Demonym | Paraguayan | |||||

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic | |||||

| • | President | Horacio Cartes | ||||

| • | Vice President | Juan Afara | ||||

| Legislature | Congress | |||||

| • | Upper house | Chamber of Senators | ||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||

| Independence from Spain | ||||||

| • | Declared | 14 May 1811 | ||||

| • | Recognized | 15 May 1811 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 406,752 km2 (60th) 157,048 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 2.3 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2015 estimate | 6,783,272[2] (104th) | ||||

| • | Density | 17.2/km2 (204th) 39/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $64.115 billion (100th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $9,353 (107th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $27.323 billion (99th) | ||||

| • | Per capita | $3,986 | ||||

| Gini (2014) | high |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | medium · 112th |

|||||

| Currency | Guaraní (PYG) | |||||

| Time zone | PYT (UTC–4) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | PYST (UTC–3) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +595 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PY | |||||

| Internet TLD | .py | |||||

| a. | Mixed European and Amerindian. | |||||

Paraguay (/ˈpærəɡwaɪ/; Spanish pronunciation: [paɾaˈɣwai̯]; Guarani: Paraguái, [paɾaˈɣwaj]), officially the Republic of Paraguay (Spanish: República del Paraguay; Guarani: Tetã Paraguái), is a landlocked country in central South America, bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to the east and northeast, and Bolivia to the northwest. Paraguay lies on both banks of the Paraguay River, which runs through the center of the country from north to south. Due to its central location in South America, it is sometimes referred to as Corazón de Sudamérica ("Heart of South America").[5] Paraguay is one of the two landlocked countries (the other is Bolivia) that lie outside Afro-Eurasia. Paraguay is the smallest landlocked country in the Americas.

The indigenous Guaraní had been living in Paraguay for at least a millennium before the Spanish conquered the territory in the 16th century. Spanish settlers and Jesuit missions introduced Christianity and Spanish culture to the region. Paraguay was a peripheral colony of the Spanish Empire, with few urban centers and settlers. Following independence from Spain in 1811, Paraguay was ruled by a series of dictators who generally implemented isolationist and protectionist policies.

Following the disastrous Paraguayan War (1864–1870), the country lost 60 to 70 percent of its population through war and disease, and about 140,000 square kilometers (54,054 sq mi), one quarter of its territory, to Argentina and Brazil.

Through the 20th century, Paraguay continued to endure a succession of authoritarian governments, culminating in the regime of Alfredo Stroessner, who led South America's longest-lived military dictatorship from 1954 to 1989. He was toppled in an internal military coup, and free multi-party elections were organized and held for the first time in 1993. A year later, Paraguay joined Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay to found Mercosur, a regional economic collaborative.

As of 2009, Paraguay's population was estimated to be at around 6.5 million, most of whom are concentrated in the southeast region of the country. The capital and largest city is Asunción, of which the metropolitan area is home to nearly a third of Paraguay's population. In contrast to most Latin American nations, Paraguay's indigenous language and culture, Guaraní, remains highly influential. In each census, residents predominantly identify as mestizo, reflecting years of intermarriage among the different ethnic groups. Guaraní is recognized as an official language alongside Spanish, and both languages are widely spoken in the country.

Etymology

There is no consensus for the derivation or meaning of the name Paraguay, although many versions are similar. The most common interpretations include:

- "Born from water" (derived from para "water" and guay "born" from the Guarani language)[6]

- "Riverine of many varieties" (also derived from Guarani, from para' "of many varieties" and gua "riverine")

- "River which originates a sea"

- Fray Antonio Ruiz de Montoya (1585–1652) said that it meant "river crowned."

- The Spanish officer and scientist Félix de Azara (1746–1821) suggests two derivations: the Payaguas (Payaguá-ý", or "river of Payaguás"), referring to the indigenous tribe who lived along the river, or a great chief named "Paraguaio."

- The French-Argentine historian and writer Paul Groussac (1848–1929) argued that it meant "river that flows through the sea (Pantanal)."

- Paraguayan poet and ex-president Juan Natalicio González (1897–1966) said it meant "river of the habitants of the sea."

History

Pre-Columbian Era

Indigenous peoples have inhabited this area for thousands of years. Pre-Columbian society in the region which is now Paraguay consisted of semi-nomadic tribes that were known for their warrior traditions. These indigenous tribes belonged to five distinct language families, which was the basis of their major divisions. Differing language groups were generally competitive over resources and territories. They were further divided into tribes by speaking languages in branches of these families. Today 17 separate ethnolinguistic groups remain.

Colonization

The first Europeans in the area were Spanish explorers in 1516.[7] The Spanish explorer Juan de Salazar de Espinosa founded the settlement of Asunción on 15 August 1537. The city eventually became the center of a Spanish colonial province of Paraguay.

An attempt to create an autonomous Christian Indian nation [8] was undertaken by Jesuit missions and settlements in this part of South America in the eighteenth century, which included portions of Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil. They developed Jesuit reductions to bring Guarani populations together at Spanish missions and protect them from virtual slavery by Spanish settlers, in addition to seeking their conversion to Christianity. Catholicism in Paraguay was influenced by the indigenous peoples; the syncretic religion has absorbed native elements. The reducciones flourished in Eastern Paraguay for about 150 years, until the expulsion of the Jesuits by the Spanish Crown in 1767. The ruins of two 18th-century Jesuit Missions of La Santísima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue have been designated as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.[8]

Independence and rule of Francia

Paraguay overthrew the local Spanish administration on 14 May 1811. Paraguay's first dictator was José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia who ruled Paraguay from 1814 until his death in 1840, with very little outside contact or influence. He intended to create a utopian society based on the French theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Social Contract.[9]

Rodríguez de Francia established new laws that greatly reduced the powers of the Catholic church (Catholicism was then an established state religion) and the cabinet, forbade colonial citizens from marrying one another and allowed them to marry only blacks, mulattoes or natives, in order to break the power of colonial-era elites and to create a mixed-race or mestizo society.[10] He cut off relations between Paraguay and the rest of South America. Because of Francia's restrictions of freedom, Fulgencio Yegros and several other Independence-era leaders in 1820 planned a coup d’état against Francia, who discovered the plot and had its leaders either executed or imprisoned for life.

Lopez family

After Francia's death in 1840, Paraguay was ruled by various military officers under a new junta, until Carlos Antonio López (allegedly De Francia's nephew) came to power in 1841. López modernized Paraguay and opened it to foreign commerce. He signed a non-aggression pact with Argentina and officially declared independence of Paraguay in 1842. After López's death in 1862, power was transferred to his eldest son, Francisco Solano López.

The regime of the López family was characterized by pervasive and rigid centralism in production and distribution. There was no distinction between the public and the private spheres, and the López family ruled the country as it would a large estate.[11]

The government exerted control on all exports. The export of yerba mate and valuable wood products maintained the balance of trade between Paraguay and the outside world.[12] The Paraguayan government was extremely protectionist, never accepted loans from abroad and levied high tariffs against imported foreign products. This protectionism made the society self-sufficient, and it also avoided the debt suffered by Argentina and Brazil. Slavery existed in Paraguay, although not in great numbers, until 1844, when it was legally abolished in the new Constitution.[13]

Francisco Solano López, the son of Carlos Antonio López, replaced his father as the President-Dictator in 1862, and generally continued the political policies of his father. Both wanted to give an international image of Paraguay as "democratic and republican", but in fact, the ruling family had almost total control of all public life in the country, including Church and colleges.[14]

Militarily, Carlos Antonio López modernized and expanded industry and the Paraguayan Army and greatly strengthened the strategic defences of Paraguay by developing the Fortress of Humaitá.[15] The government hired more than 200 foreign technicians, who installed telegraph lines and railroads to aid the expanding steel, textile, paper and ink, naval construction, weapons and gunpowder industries. The Ybycuí foundry, completed in 1850, manufactured cannons, mortars and bullets of all calibers. River warships were built in the shipyards of Asunción. Fortifications were built, especially along the Apa River and in Gran Chaco.[16]:22 The work was continued by his son Francisco Solano.

According to George Thompson, C.E., Lieutenant Colonel of Engineers in the Paraguayan Army prior to and during the war, López's government was comparatively a good one for Paraguay:

Probably in no other country in the world has life and property been so secure as all over Paraguay during his (Antonio Lopez's) reign. Crime was almost unknown, and when committed, immediately detected and punished. The mass of the people was, perhaps, the happiest in existence. They had hardly to do any work to gain a livelihood. Each family had its house or hut in its own ground. They planted, in a few days, enough tobacco, maize and mandioca for their own consumption [...]. Having at every hut a grove of oranges [...] and also a few cows, they were almost throughout the year under little necessity [...]. The higher classes, of course, lived more in an European way.— George Thompson, C.E.[17]

Paraguayan War (1864–1870)

In 12 October 1864, despite Paraguayan ultimatums, the Brazilian Empire (sided with Argentina and the rebellious Gen. Venancio Flores) invaded the Republic of Uruguay (which then was an ally of the Lopez's Government), thus starting the Paraguayan War.[18] The Paraguayans, led by the Marshal of the Republic Francisco Solano López, held a fierce resistance, but were ultimately defeated in 1870 after the Death of Solano López, who was killed in action.[19] The real causes of this war, which remains the bloodiest international conflict in Latin American history, are still highly debated.[20]

About the disaster suffered by the Paraguayans at the outcome of the war, William D. Rubinstein wrote: "The normal estimate is that of a Paraguayan population of somewhere between 450,000 and 900,000, only 220,000 survived the war, of whom only 28,000 were adult males."[21] Paraguay also suffered extensive territorial losses to Brazil and Argentina.

During the pillaging of Asunción in 1869, the Brazilian Imperial Army packed up and transported the Paraguayan National Archives to Rio de Janeiro.[22][23] Brazil's records from the war have remained classified.[24] This has made Paraguayan history in the Colonial and early National periods difficult to research and study.

20th century

In 1904 the Liberal revolution against the rule of Colorados broke out. The Liberal rule started a period of great political instability. Between 1904 and 1954 Paraguay had thirty-one presidents, most of whom were removed from office by force.[25] Conflicts between the factions of the ruling Liberal party led to the Paraguayan Civil War of 1922.

The unresolved border conflict with Bolivia over Chaco region finally erupted in early 1930s in the Chaco War. After great losses Paraguay defeated Bolivia and established its sovereignty over most of the disputed Chaco region. After the war military officers used popular dissatisfaction with the Liberal politicians to grab the power for themselves. On 17 February 1936 the February Revolution brought colonel Rafael Franco to power. Between 1940 and 1948 the country was ruled by general Higinio Moríñigo. Dissatisfaction with his rule resulted in the Paraguayan civil war of 1947.[26] In its aftermath Alfredo Stroessner began involvement in a string of plots, which resulted in his military coup d'état of 4 May 1954.

Stroessner

A series of unstable governments ensued until the establishment in 1954 of the regime of dictator Alfredo Stroessner, who remained in office for more than three decades until 1989. Paraguay was modernized to some extent under Stroessner's regime, although his rule was marked by extensive civil right abuses.[27]

Stroessner and the Colorado party ruled the country from 1954 to 1989. The dictator oversaw an era of economic expansion, but also had a poor human rights and environmental record (see "Political History"). Torture and death for political opponents was routine. After his overthrow, the Colorado continued to dominate national politics until 2008.

The splits in the Colorado Party in the 1980s, and the prevailing conditions: Stroessner's advanced age, the character of the regime, the economic downturn, and international isolation, were catalysts for anti-regime demonstrations and statements by the opposition prior to the 1988 general elections.

PLRA leader Domingo Laino served as the focal point of the opposition in the second half of the 1980s. The government's effort to isolate Laino by exiling him in 1982 had backfired. On his sixth attempt to re-enter the country in 1986, Laino returned with three television crews from the U.S., a former United States ambassador to Paraguay, and a group of Uruguayan and Argentine congressmen. Despite the international contingent, the police violently barred Laino's return.

The Stroessner regime relented in April 1987, and permitted Laino to return to Asunción. Laino took the lead in organizing demonstrations and reducing infighting among the opposition party. The opposition was unable to reach agreement on a common strategy regarding the elections, with some parties advocating abstention, and others calling for blank voting. The parties held numerous 'lightning demonstrations' (mítines relámpagos), especially in rural areas. Such demonstrations were gathered and quickly disbanded before the arrival of the police.

In response to the upsurge in opposition activities, Stroessner condemned the Accord for advocating "sabotage of the general elections and disrespect of the law." He used national police and civilian vigilantes of the Colorado Party to break up demonstrations. A number of opposition leaders were imprisoned or otherwise harassed. Hermes Rafael Saguier, another key leader of the PLRA, was imprisoned for four months in 1987 on charges of sedition. In early February 1988, police arrested 200 people attending a National Coordinating Committee meeting in Coronel Oviedo. Laino and several other opposition figures were arrested before dawn on the day of the election, 14 February, and held for twelve hours. The government declared Stroessner's re-election with 89% of the vote.[28]

The opposition attributed the results in part to the virtual Colorado monopoly on the mass media. They noted that 53% of those polled indicated that there was an "uneasiness" in Paraguayan society. 74% believed that the political situation needed changes, including 45% who wanted a substantial or total change. Finally, 31% stated that they planned to abstain from voting in the February elections.

On 3 February 1989, Stroessner was overthrown in a military coup headed by General Andrés Rodríguez. As president, Rodríguez instituted political, legal, and economic reforms and initiated a rapprochement with the international community. Reflecting the deep hunger of the rural poor for land, hundreds immediately occupied thousands of acres of unused territories belonging to Stroessner and his associates; by mid-1990, 19,000 families occupied 340,000 acres (137,593 ha). At the time, 2.06 million people lived in rural areas, more than half of the 4.1 million total population, and most were landless.[29]

Post-1989

The June 1992 constitution established a democratic system of government and dramatically improved protection of fundamental human rights. In May 1993, Colorado Party candidate Juan Carlos Wasmosy was elected as Paraguay's first civilian president in almost 40 years, in what international observers deemed fair and free elections.

With support from the United States, the Organization of American States, and other countries in the region, the Paraguayan people rejected an April 1996 attempt by then Army Chief General Lino Oviedo to oust President Wasmosy.

Oviedo was nominated as the Colorado candidate for president in the 1998 election, however, when the Supreme Court upheld in April his conviction on charges related to the 1996 coup attempt, he was not allowed to run and was detained in jail. His former running mate, Raúl Cubas, became the Colorado Party's candidate, and was elected in May in elections deemed by international observers to be free and fair. One of Cubas' first acts after taking office in August was to commute Oviedo's sentence and release him. In December 1998, Paraguay's Supreme Court declared these actions unconstitutional. In this tense atmosphere, the murder of Vice President and long-time Oviedo rival Luis María Argaña on 23 March 1999, led the Chamber of Deputies to impeach Cubas the next day. On 26 March, eight student anti-government demonstrators were murdered, widely believed to have been carried out by Oviedo supporters. This increased opposition to Cubas, who resigned on 28 March. Senate President Luis González Macchi, a Cubas opponent, was peacefully sworn in as president the same day.

In 2003, Nicanor Duarte Frutos was elected as president.

For the 2008 general elections, the Colorado Party was favored in polls. Their candidate was Minister of Education Blanca Ovelar, the first woman to be nominated as a candidate for a major party in Paraguayan history. After sixty years of Colorado rule, voters chose Fernando Lugo, a former Roman Catholic Bishop and not a professional politician in civil government. He had long followed liberation theology, which was controversial in South American societies, but he was backed by the center-right Liberal Party, the Colorado Party's traditional opponents.

From Lugo's 2008 election to his 2012 impeachment

Lugo achieved a historic victory in Paraguay's presidential election, defeating the ruling party candidate, and ending 61 years of conservative rule. Lugo won with nearly 41% of the vote, compared to almost 31% for Blanca Ovelar of the Colorado party.[30] Outgoing President Nicanor Duarte Frutos hailed the moment as the first time in the history of the nation that a government had transferred power to opposition forces in a constitutional and peaceful fashion.

Lugo was sworn in on 15 August 2008. The Paraguayan Congress continued to be dominated by right-wing elected officials. The Lugo administration set its two major priorities as the reduction of corruption and economic inequality.[31]

Political instability following Lugo's election and disputes within his cabinet encouraged some renewal of popular support for the Colorado Party. Reports suggested that the businessman Horacio Cartes became the new political figure amid disputes. Despite the US Drug Enforcement Administration's strong accusations against Cartes related to drug trafficking, he continued to amass followers in the political arena.

On 14 January 2011, the Colorado Party convention nominated Horacio Cartes as the presidential candidate for the party. However, the party's constitution didn't allow it. On 21 June 2012, impeachment proceedings against President Lugo began in the country's lower house, which was controlled by his opponents. Lugo was given less than twenty-four hours to prepare for the proceedings and only two hours in which to mount a defense.[32] Impeachment was quickly approved and the resulting trial in Paraguay's Senate, also controlled by the opposition, ended with the removal of Lugo from office and Vice President Federico Franco assuming the duties of president.[33] Lugo's rivals blamed him for the deaths of 17 people – eight police officers and nine farmers – in armed clashes after police were ambushed by armed peasants when enforcing an eviction order against rural trespassers.[34]

Lugo's supporters gathered outside Congress to protest the decision as a "politically motivated coup d'état".[33] Lugo's removal from office on 22 June 2012 is considered by UNASUR and other neighboring countries, especially those currently governed by leftist leaders, as a coup d'état.[35] The Organization of American States, which sent a mission to Paraguay to gather information, concluded that the impeachment process had been carried out in accordance with the Constitution of Paraguay.

Geography

Paraguay is divided by the Río Paraguay into two well differentiated geographic regions. The eastern region (Región Oriental); and the western region, officially called Western Paraguay (Región Occidental) and also known as the Chaco, which is part of the Gran Chaco. The country lies between latitudes 19° and 28°S, and longitudes 54° and 63°W. The terrain consists mostly of grassy plains and wooded hills in the eastern region. To the west are mostly low, marshy plains.

Climate

The overall climate is tropical to subtropical. Like most lands in the region, Paraguay has only wet and dry periods. Winds play a major role in influencing Paraguay's weather: between October and March, warm winds blow from the Amazon Basin in the North, while the period between May and August brings cold winds from the Andes.

The absence of mountain ranges to provide a natural barrier allows winds to develop speeds as high as 161 km/h (100 mph). This also leads to significant changes in temperature within a short span of time; between April and September, temperatures will sometimes drop below freezing. January is the hottest summer month, with an average daily temperature of 28.9 degrees Celsius (84 degrees F).

Rainfall varies dramatically across the country, with substantial rainfall in the eastern portions, and semi-arid conditions in the far west. The far eastern forest belt receives an average of 170 centimeters (67 inches) of rain annually, while the western Chaco region typically averages no more than 50 cm (20 in) a year. The rains in the west tend to be irregular and evaporate quickly, contributing to the aridity of the area.

Government and politics

Paraguay is a representative democratic republic, with a multi-party system and separation of powers in three branches. Executive power is exercised solely by the President, who is head of state and head of government. Legislative power is vested in the two chambers of the National Congress. The judiciary is vested on tribunals and Courts of Civil Law and a nine-member Supreme Court of Justice, all of them independent of the executive and the legislature.

Military

The military of Paraguay consist of the Paraguayan army, navy (including naval aviation and marine corps) and air force.

The constitution of Paraguay establishes the president of Paraguay as the commander-in-chief.

Paraguay has compulsory military service, and all 18-year-old males and 17-year-olds in the year of their 18th birthday are liable for one year of active duty. Although the 1992 constitution allows for conscientious objection, no enabling legislation has yet been approved.

In July 2005, military aid in the form of U.S. Special Forces began arriving at Paraguay's Mariscal Estigarribia air base, a sprawling complex built in 1982.[36][37]

Administrative subdivisions

Paraguay consists of seventeen departments and one capital district (distrito capital).

It is also divided into 2 regions: The "Occidental Region" or Chaco (Boquerón, Alto Paraguay and Presidente Hayes), and the "Oriental Region" (the other departments and the capital district).

These are the departments, with their capitals, population, area and the number of districts:

| ISO 3166-2:PY | Departament | Capital | Population (2002 census) | Area (km²) | Districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASU | Distrito Capital | Asunción | 512,112 | 117 | 6 |

| 1 | Concepción | Concepción | 179,450 | 18,051 | 8 |

| 2 | San Pedro | San Pedro | 318,698 | 20,002 | 20 |

| 3 | Cordillera | Caacupé | 233,854 | 4,948 | 20 |

| 4 | Guairá | Villarrica | 178,650 | 3,846 | 18 |

| 5 | Caaguazú | Coronel Oviedo | 435,357 | 11,474 | 21 |

| 6 | Caazapá | Caazapá | 139,517 | 9,496 | 10 |

| 7 | Itapúa | Encarnación | 453,692 | 16,525 | 30 |

| 8 | Misiones | San Juan Bautista | 101,783 | 9,556 | 10 |

| 9 | Paraguarí | Paraguarí | 221,932 | 8,705 | 17 |

| 10 | Alto Paraná | Ciudad del Este | 558,672 | 14,895 | 21 |

| 11 | Central | Areguá | 1,362,893 | 2,465 | 19 |

| 12 | Ñeembucú | Pilar | 76,348 | 12,147 | 16 |

| 13 | Amambay | Pedro Juan Caballero | 114,917 | 12,933 | 4 |

| 14 | Canindeyú | Salto del Guairá | 140.137 | 14.667 | 12 |

| 15 | Presidente Hayes | Villa Hayes | 82,493 | 72,907 | 8 |

| 16 | Alto Paraguay | Fuerte Olimpo | 11,587 | 82,349 | 4 |

| 17 | Boquerón | Filadelfia | 41,106 | 91,669 | 3 |

| – | Paraguay | Asunción | 5,163,198 | 406,752 | 245 |

The departments are further divided into districts (distritos).

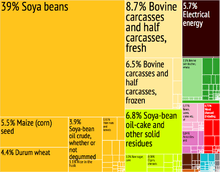

Economy

The macro-economy in Paraguay has some unique characteristics. It is characterized by a historical low inflation rate – 5% average (in 2013, the inflation rate was 3.7%), international reserves 20% of GDP and twice the amount of the external national debt. On top of that, the country enjoys clean and renewable energy production of 8,700 MW (current domestic demand 2,300 MW).[38]

Between 1970 and 2013, the country had the highest economic growth of South America, with an average rate of 7.2% per year.

In 2010 and 2013, Paraguay experienced the greatest economic expansion of South America, with a GDP growth rate of 14.5% and 13.6% respectively.[39]

Paraguay is the fourth-largest soybean producer in the world, second-largest producer of stevia, second-largest producer of tung oil, sixth-largest exporter of corn, tenth-largest exporter of wheat and 8th largest exporter of beef.

The market economy is distinguished by a large informal sector, featuring re-export of imported consumer goods to neighboring countries, as well as the activities of thousands of microenterprises and urban street vendors. Nonetheless, over the last 10 years the Paraguayan economy diversified dramatically, with the energy, auto parts and clothing industries leading the way.[40]

The country also boasts the third most important free commercial zone in the world: Ciudad del Este, trailing behind Miami and Hong Kong. A large percentage of the population, especially in rural areas, derives its living from agricultural activity, often on a subsistence basis. Because of the importance of the informal sector, accurate economic measures are difficult to obtain. The economy grew rapidly between 2003 and 2013 as growing world demand for commodities combined with high prices and favorable weather to support Paraguay's commodity-based export expansion.

In 2012, Paraguay's government introduced the MERCOSUR(FOCEM) system in order to stimulate the economy and job growth through a partnership with both Brazil and Argentina.[41]

Industry and manufacturing

The mineral industry of Paraguay produces about 25% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) and employs about 31% of the labor force. Production of cement, iron ore, and steel occurs commonly throughout Paraguay's industrial sector. The growth of the industry was further fueled by the maquila industry, with large industrial complexes located in the eastern part of the country. Paraguay put in place many incentives aimed to attract industries to the country. One of them is the so-called "Maquila law" by which companies can relocate to Paraguay, enjoying minimal tax rates.[42]

In the pharmaceutical industry, Paraguayan companies now meet 70% of domestic consumption and have begun to export drugs. Paraguay is quickly supplanting foreign suppliers in meeting the country's drug needs. Strong growth also is evident in the production of edible oils, garments, organic sugar, meat processing, and steel.

In 2003 manufacturing made up 13.6% of the GDP, and the sector employed about 11% of the working population in 2000. Paraguay's primary manufacturing focus is on food and beverages. Wood products, paper products, hides and furs, and non-metallic mineral products also contribute to manufacturing totals. Steady growth in the manufacturing GDP during the 1990s (1.2% annually) laid the foundation for 2002 and 2003, when the annual growth rate rose to 2.5%.[43]

Social issues

Various poverty estimates suggest that 30–50% of the population is poor.[44] In rural areas, 41.20% of the people lack a monthly income to cover basic necessities, whereas in urban centers this figure is 27.6%. The top 10% of the population holds 43.8% of the national income, while the lowest 10% has 0.5%. The economic recession has worsened income inequality, notably in the rural areas, where the Gini coefficient has risen from 0.56 in 1995 to 0.66 in 1999.

More recent data (2009)[45] show that 35% of the Paraguayan population is poor, 19% of which live in extreme poverty. Moreover, 71% of the latter live in rural areas of the country.

Similarly, land concentration in the Paraguayan countryside is one of the highest in the globe: 10% of the population controls 66% of the land, while 30% of the rural people are landless.[46] In the immediate aftermath of the 1989 overthrow of Stroessner, some 19,000 rural families occupied hundreds of thousands of acres of unused lands formerly held by the dictator and his associates by mid-1990, but many rural poor remained landless. This inequality has caused a great deal of tensions between the landless and land owners.[29]

Social issues of the indigenous

Literacy rates are extremely low among Paraguay's indigenous population, who have an illiteracy rate of 51% compared to the 7.1% rate of the general population.[47]

Only 2.5% of Paraguay's indigenous population has access to clean drinking water and only 9.5% have electricity.[47]

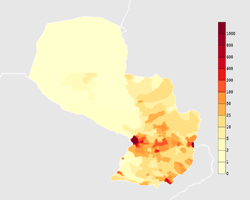

Demographics

Paraguay's population is distributed unevenly through the country, with the vast majority of people living in the eastern region near the capital and largest city, Asunción, which accounts for 10% of the country's population. The Gran Chaco region, which includes the Alto Paraguay, Boquerón and Presidente Hayes Department, and accounts for about 60% of the territory, is home to less than 2% of the population. About 56% of Paraguayans live in urban areas, making Paraguay one of the least urbanized nations in South America.

For most of its history, Paraguay has been a recipient of immigrants, owing to its low population density, especially after the demographic collapse that resulted from the Paraguayan War. Small groups of ethnic Italians, Germans, Russians, Japanese, Koreans, Chinese, Arabs, Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, Brazilians, and Argentines have also settled in Paraguay. Many of these communities have retained their languages and culture, particularly the Brazilians, who represent the largest and most prominent immigrant group, at around 400,000.[48] Many Brazilian Paraguayans are of German, Italian and Polish descent.[49] There are an estimated 63,000 Afro-Paraguayans, comprising 1% of the population.[50]

There is no official data on the ethnic composition of the Paraguayan population, as the Department of Statistics, Surveys and Censuses[51] of Paraguay does not ask about race and ethnicity in census surveys, although it does inquire about the indigenous population. According to the census of 2002, the indigenous people made up 1.7% of Paraguay's total population.[52]

Traditionally, the majority of the Paraguayan population is considered mixed (mestizo in Spanish). HLA-DRB1 polymorphism studies have shown the genetic distances between Paraguayans and Spanish populations were closer than between Paraguayans and Guaranis. Altogether these results suggest the predominance of the Spanish genetic in the Paraguayan population.[53] According to the CIA World Factbook, Paraguay has a population of 6,669,086, 95% of which are mestizo (mixed European and Amerindian) and 5% are labelled as "other",[2] which includes members of indigenous tribal groups. They are divided into 17 distinct ethnolinguistic groupings, many of which are poorly documented. Paraguay has one of the most prominent German communities in South America, with some 25,000 German-speaking Mennonites living in the Paraguayan Chaco.[54] German settlers founded several towns as Hohenau, Filadelfia, Neuland, Obligado and Nueva Germania. Several websites that promote German immigration to Paraguay claim that 5–7% of the population is of German ancestry, including 150,000 people of German-Brazilian descent.[55][56][57][58][59]

Religion

Christianity, particularly Roman Catholicism, is the dominant religion in Paraguay. According to the 2002 census, 89.9% of the population is Catholic, 6.2% is Evangelical Protestant, 1.1% identify with other Christian sects, and 0.6% practice indigenous religions. A U.S. State Department report on Religious Freedom names Roman Catholicism, evangelical Protestantism, mainline Protestantism, Judaism (Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform), Mormonism, and the Baha'i Faith as prominent religious groups. It also mentions a large Muslim community in Alto Paraná (as a result of Middle-Eastern immigration, especially from Lebanon) and a prominent Mennonite community in Boquerón.[60]

Languages

One remarkable trace of the indigenous Guaraní culture that has endured in Paraguay is the Guaraní language which is generally understood by 95% of the population. Additionally, Spanish is understood by about 90 percent of the population, which alongside Guaraní is an official language.[61] During the late 1980s, Spanish was spoken just by 75% of Paraguay's population.[62]

Largest cities

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||

Asunción  Ciudad del Este |

1 | Asunción | Capital District | 512,112 | 11 | Mariano Roque Alonso | Central | 65,229 | San Lorenzo  Luque |

| 2 | Ciudad del Este | Alto Paraná | 222,274 | 12 | Pedro Juan Caballero | Amambay | 64,592 | ||

| 3 | San Lorenzo | Central | 204,356 | 13 | Villa Elisa | Central | 53,166 | ||

| 4 | Luque | Central | 170,986 | 14 | Caaguazú | Caaguazú | 48,941 | ||

| 5 | Capiatá | Central | 154,274 | 15 | Coronel Oviedo | Caaguazú | 48,773 | ||

| 6 | Lambaré | Central | 119,795 | 16 | Hernandarias | Alto Paraná | 47,266 | ||

| 7 | Fernando de la Mora | Central | 113,560 | 17 | Presidente Franco | Alto Paraná | 47,246 | ||

| 8 | Limpio | Central | 73,158 | 18 | Itauguá | Central | 45,577 | ||

| 9 | Ñemby | Central | 71,909 | 19 | Concepción | Concepción | 44,070 | ||

| 10 | Encarnación | Itapúa | 67,173 | 20 | Villarrica | Guairá | 38,961 | ||

Culture

Paraguay's cultural heritage can be traced to the extensive intermarriage between the original male Spanish settlers and indigenous Guaraní women. Their culture is highly influenced by various European countries, including Spain. Therefore, Paraguayan culture is a fusion of two cultures and traditions; one European, the other, Southern Guaraní. More than 93% of Paraguayans are mestizos, making Paraguay one of the most homogeneous countries in Latin America. A characteristic of this cultural fusion is the extensive bilingualism present to this day: more than 80% of Paraguayans speak both Spanish and the indigenous language, Guaraní. Jopara, a mixture of Guaraní and Spanish, is also widely spoken.

This cultural fusion is expressed in arts such as embroidery (ao po'í) and lace making (ñandutí). The music of Paraguay, which consists of lilting polkas, bouncy galopas, and languid guaranias is played on the native harp. Paraguay's culinary heritage is also deeply influenced by this cultural fusion. Several popular dishes contain manioc, a local staple crop similar to the yuca also known as Cassava root found in the Southwestern United States and Mexico, as well as other indigenous ingredients. A popular dish is sopa paraguaya, similar to a thick corn bread. Another notable food is chipa, a bagel-like bread made from cornmeal, manioc, and cheese. Many other dishes consist of different kinds of cheeses, onions, bell peppers, cottage cheese, cornmeal, milk, seasonings, butter, eggs and fresh corn kernels.

The 1950s and 1960s were the time of the flowering of a new generation of Paraguayan novelists and poets such as José Ricardo Mazó, Roque Vallejos, and Nobel Prize nominee Augusto Roa Bastos. Several Paraguayan films have been made.

Inside the family, conservative values predominate. In lower classes, godparents have a special relationship to the family, since usually, they are chosen because of their favorable social position, in order to provide extra security for the children. Particular respect is owed them, in return for which the family can expect protection and patronage.

Sports

Education

Literacy was about 93.6% and 87.7% of Paraguayans finish the 5th grade according to UNESCO's last Educational Development Index 2008. Literacy does not differ much by gender.[64] A more recent study[45] reveals that attendance at primary school by children between 6 and 12 years old is about 98%. Primary education is free and mandatory and takes nine years. Secondary education takes three years.[64] Paraguay's universities include:

- National University of Asunción (public and founded in 1889)[65]

- Autonomous University of Asunción (private and founded in 1979)[66]

- Universidad Católica Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (private and run by the church).[67]

- Universidad Americana (private).

The net primary enrollment rate was at 88% in 2005.[64] Public expenditure on education was about 4.3% of GDP in the early 2000s.[64]

Health

Average life expectancy in Paraguay is rather high given its poverty: as of 2006, it was 75 years,[68] equivalent to far wealthier Argentina, and the 8th highest in the Americas according to World Health Organization. Public expenditure on health is 2.6% of GDP, while private health expenditure is 5.1%.[64] Infant mortality was 20 per 1,000 births in 2005.[64] Maternal mortality was 150 per 100,000 live births in 2000.[64] The World Bank has helped the Paraguayan government reduce the country's maternal and infant mortality. The Mother and Child Basic Health Insurance Project aimed to contribute to reducing mortality by increasing the use of selected life-saving services included in the country's Mother and Child Basic Health Insurance Program (MCBI) by women of child-bearing age, and children under age six in selected areas. To this end, the project also targeted improving the quality and efficiency of the health service network within certain areas, in addition to increasing the Ministry of Public Health and Social Welfare's (MSPBS) management.[69]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "Paraguay". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- 1 2 "The World Factbook: Paraguay". Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ↑ "2015 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ "En el corazón de Sudamérica". ABC. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Paraguay". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Sacks, Richard S. "Early explorers and conquistadors". In Hanratty & Meditz.

- 1 2 "Paraguariae Provinciae Soc. Jesu cum Adiacentibg. Novissima Descriptio" [A Current Description of the Province of the Society of Jesus in Paraguay with Neighboring Areas]. World Digital Library (in Latin). 1732.

- ↑ War of The Triple Alliance, War of the Pacific. Retrieved 14 November 2010

- ↑ Romero, Simon. "In Paraguay, Indigenous Language With Unique Staying Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Carlos Antonio López", Library of Congress Country Studies, December 1988. URL accessed 30 December 2005.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6 ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/ Bartleby.com.

Page 630

- ↑ Cunninghame Graham 1933, p. 39-40.

- ↑ Cunninghame Graham 1933, p. 41-42.

- ↑ Robert Cowley, The Reader's Encyclopedia to Military History. New York, New York: Houston Mifflin, 1996. Page 479.

- ↑ Hooker, T.D., 2008, The Paraguayan War, Nottingham: Foundry Books, ISBN 1901543153

- ↑ Thompson 1869, p. 10.

- ↑ Sir Richard Francis Burton: "Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay", p.76 - Tinsley Brothers Editors - London (1870) - Burton, as a witness of the conflict, marks this date (12-16 October 1864) as the real beginning of the war. He writes (and it's the most logic account, considering the facts): The Brazilian Army invades the Banda Oriental, despite the protestations of President López, who declared that such invasion would be held a "casus belli".

- ↑ Hooker, T.D., 2008, "The Paraguayan War". Nottingham: Foundry Books, pp. 105-108. ISBN 1901543153

- ↑ The classical view asserts that Francisco Solano López's expansionist and hegemonic views are the main reason for the outbreak of the conflict. The traditional paraguayan view, held by the "lopistas" (supporters of Solano López, both in Paraguay and worldwide), affirms that Paraguay acted in self-defense and for the protection of the "Equilibrium of the Plate Basin". This view is usually contested by the "anti-lopistas" (also known in Paraguay as "legionarios"), who favoured the "Triple Alliance". Revisionist views, both from right and left wing national-populists, put a great emphasis on the influence of the British Empire in the conflict, a view that is discarded by a majority of historians.

- ↑ Rubinsein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. p. 94. ISBN 0-582-50601-8.

- ↑ Hipólito Sanchez Quell: "Los 50.000 Documentos Paraguayos Llevados al Brasil". Ediciones Comuneros, Asunción (2006).

- ↑ Some of the documents taken by Brasil during the war, were returned to Paraguay in the collection known as "Colección de Río Branco", nowadays in the National Archives of Asunción, Paraguay

- ↑ Barbara Weinstein (28 January 2008). "Let the Sunshine In: Government Records and National Insecurities". Historians.org. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Hanratty, Dannin M.; Meditz, Sandra W. (1988). "Paraguay: A Country Study". Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Paraguay Civil War 1947". Onwar.com. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Bernstein, Adam (17 August 2006). "Alfredo Stroessner; Paraguayan Dictator". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "Paraguayan Wins His Eighth Term", The New York Times, 15 February 1988.

- 1 2 Nagel, Beverly Y.(1999) "'Unleashing the Fury': The Cultural Discourse of Rural Violence and Land Rights in Paraguay", in Comparative Studies in Society and History, 1999, Vol. 41, Issue 1: 148–181. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Nickson, Andrew (2009). "The general election in Paraguay, April 2008". Journal of Electoral Studies. 28 (1): 145–9. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2008.10.001.

- ↑ "Paraguay". State.gov. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Mark Weisbrot (22 June 2012). "What will Washington do about Fernando Lugo's ouster in Paraguay?". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- 1 2 Mariano Castillo (22 June 2012). "Paraguayan Senate removes president". CNN. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ↑ Daniela Desantis (21 June 2012). "Paraguay's president vows to face impeachment effort". Reuters US edition. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ↑ "COMUNICADO UNASUR Asunción, 22 de Junio de 2012" (in Spanish). UNASUR. 22 June 2012. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Military Moves in Paraguay Rattle Regional Relations". International Relations Center. 14 December 2005. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved April 2006. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ US Marines put a foot in Paraguay, El Clarín, 9 September 2005 (Spanish)

- ↑ Focus. opportunitiesinparaguay.com

- ↑ BCP – Banco Central del Paraguay. Bcp.gov.py. Retrieved on 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Paraguay un milagro americano" (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Subsecretaria De Estado De Economia – ¿Qué Es Focem?. Economia.gov.py. Retrieved on 18 June 2016.

- ↑ ÂżQuĂŠ es Maquila? | Ministerio de Industria y Comercio – Paraguay. Mic.gov.py. Retrieved on 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Paraguay" (PDF). Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ 2003 Census Bureau Household Survey

- 1 2 ${w.time}. "En Paraguay, disminuyó la pobreza entre 2003 y 2009 – ABC Color". Abc.com.py. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Marió; et al. (2004). "Paraguay: Social Development Issues for Poverty Alleviation" (PDF). World Bank report. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Paraguay." Pan-American Health Organization. (retrieved 12 July 2011)

- ↑ Paraguay Information and History. National Geographic.

- ↑ San Alberto Journal: Awful Lot of Brazilians in Paraguay, Locals Say. The New York Times. 12 June 2001.

- ↑ "Afro-Paraguayan". Joshua Project. U.S. Center for World Mission. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ↑ "Dirección General de Estadísticas, Encuestas y Censos". Dgeec.gov.py. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ CAPÍTULO III. Características Socio-Culturales y étnicas, pp. 39ff in Paraguay. Situación de las mujeres rurales (2008) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- ↑ Benitez, O; Loiseau, P; Busson, M; Dehay, C; Hors, J; Calvo, F; Durand Mura, M; Charron, D (2002). "Hispano-Indian admixture in Paraguay studied by analysis of HLA-DRB1 polymorphism". Pathologie-biologie. 50 (1): 25–9. doi:10.1016/s0369-8114(01)00263-2. PMID 11873625.

- ↑ Antonio De La Cova (28 December 1999). "Paraguay's Mennonites resent 'fast buck' outsiders". Latinamericanstudies.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ Jonathan Ross,Paraguay. "Allgemeines über Paraguay". PY: Magazin-paraguay.de. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Information um und zu Paraguay « Kategorie « Paraguay24 – Die Geschichte unserer Auswanderung". Paraguay24.de. 23 September 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Miran Blanco (24 March 2007). "Paraguay Auswandern Einwandern Immobilien Infos für Touristen, Auswanderer Asuncion Paraguay". Auswandern-paraguay.org. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Paraguay – Immobilien – Auswandern – Immobilienschnδppchen, Hδuser, und Grundstόcke um Villarrica". My-paraguay.com. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Paraguay – Auswandern – Immobilien – Reisen". PARAGUAY1.DE. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "Paraguay religion". State.gov. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "Background Note: Paraguay". U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ↑ Federal Research Division (December 1988). "A Country Study: Paraguay". Country Studies. Society: Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ "3218.0 - Censo de la DGEEC, 2002". DGEEC. 2002. Retrieved 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Human Development Report 2009 – Paraguay". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "::Una::". Una.py. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Universidad Autónoma de Asunción: Educación Superior en Paraguay". UAA. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Campus de Asunción – Universidad Católica "Nuestra Señora de la Asunción"". Uca.edu.py. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "WHO | Paraguay". Who.int. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Paraguay Mother & Child Basic Health Insurance". The World Bank.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paraguay. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Government

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- National Department of Tourism (Spanish)

- Ministry of Finance with economic and Government information, available also in English (Spanish)

- Paraguay Photos

- General information

- Paraguay from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Paraguay". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Paraguay at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Paraguay at DMOZ

- Paraguay profile from the BBC News

-

Wikimedia Atlas of Paraguay

Wikimedia Atlas of Paraguay -

Geographic data related to Paraguay at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Paraguay at OpenStreetMap - Key Development Forecasts for Paraguay from International Futures

- News media

- La Rueda – Weekly reviews (Spanish)

- ABC Color (Spanish)

- Última Hora (Spanish)

- La Nación (Spanish)

- Paraguay.com (Spanish)

- Ñanduti (Spanish)

- Trade

- Travel

- Paraguay Convention & Visitor's Bureau

- Paraguay.com: Tradition, Culture, Maps, Tourism

-

Paraguay travel guide from Wikivoyage

Paraguay travel guide from Wikivoyage - Tourism in Paraguay, information, pictures and more. Turismo.com.py (Spanish)

|

|

|

| |

| |

||||

| ||||

| | ||||

| |

|

.jpg)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)